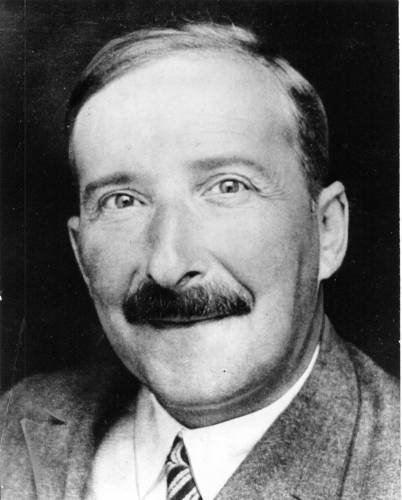

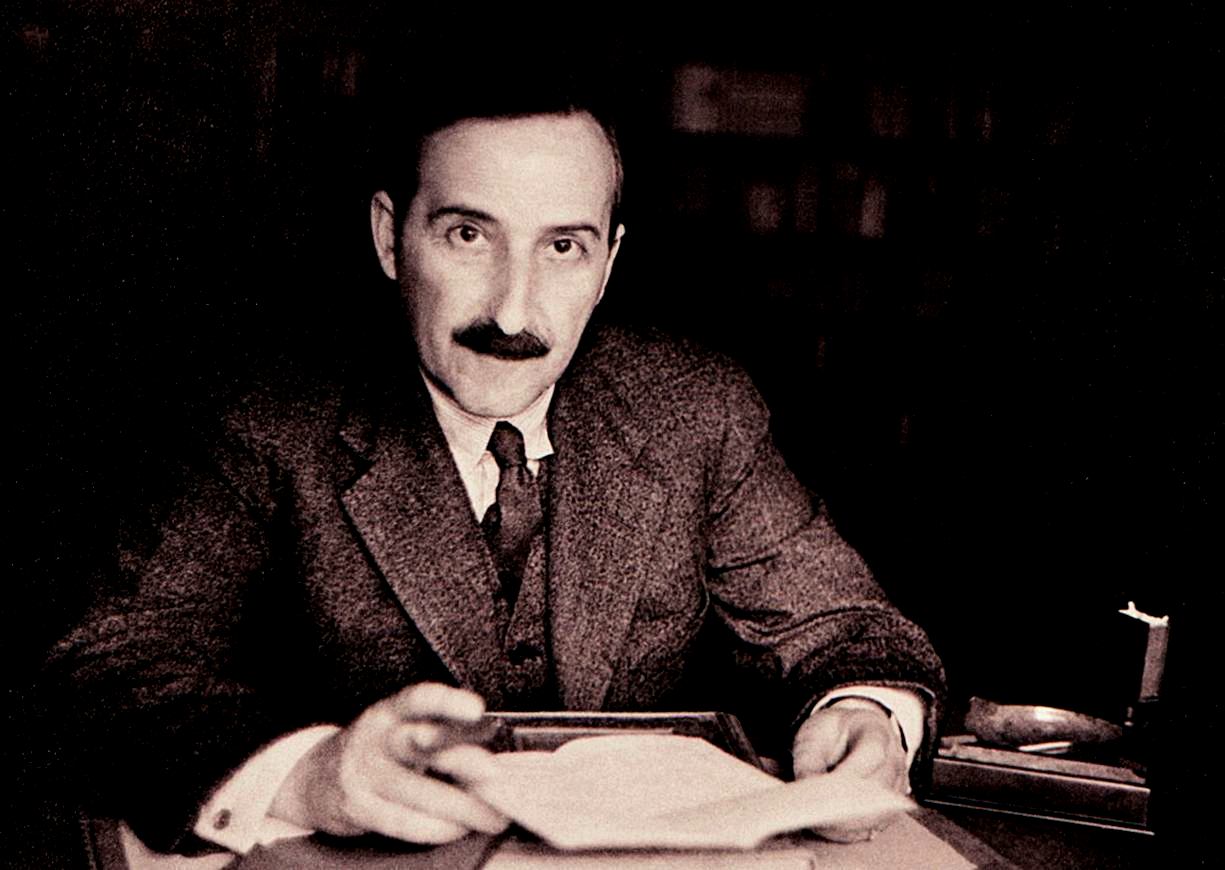

- Profession: Writer, playwright, journalist, biographer.

- Residences: Vienna, London, New York, Brazil.

- Relation to Mahler: Atlantic 1911 Eastbound 08-04-1911 until 16-04-1911 S.S. Amerika, wrote poem “Der Dirigent” for Mahlers’ 50th anniversary (see below).

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 28-11-1881 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 22-02-1942 Petropolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Aged 60. Suicide.

- Buried: Municipal cemetery, Petropolis, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Married to:

- Friderike Maria von Winternitz (born Burger) (1920-1938, divorced),

- Lotte Altmann (1939-1942, until his death).

No family relationship with Arnold Zweig (1887-1968).

Stefan Zweig was an Austrian novelist, playwright, journalist and biographer. At the height of his literary career, in the 1920s and 1930s, he was one of the most popular writers in the world. Zweig was born in Vienna, the son of Moritz Zweig (1845–1926), a wealthy Jewish textile manufacturer, and Ida Brettauer (1854–1938), a daughter of a Jewish banking family. He was related to the Czech writer Egon Hostovský, who described him as “a very distant relative”; some sources describe them as cousins.

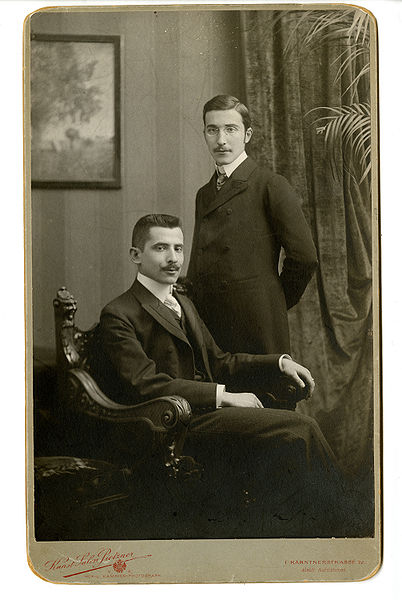

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) (standing) and his brother Alfred Zweig (1879-1977, sitting), Vienna. Approx. 1900.

Zweig studied philosophy at the University of Vienna and in 1904 earned a doctoral degree with a thesis on “The Philosophy of Hippolyte Taine”. Religion did not play a central role in his education. “My mother and father were Jewish only through accident of birth,” Zweig said later in an interview. Yet he did not renounce his Jewish faith and wrote repeatedly on Jews and Jewish themes, as in his story Buchmendel.

He had a warm relationship with Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, whom he met when Herzl was still literary editor of the Neue Freie Presse, then Vienna’s main newspaper; Herzl accepted for publication some of Zweig’s early essays. Zweig believed in internationalism and in Europeanism, as The World of Yesterday, his autobiography, makes clear. According to Amos Elon, Zweig called Herzl’s book Der Judenstaat an “obtuse text, a piece of nonsense”.

At the beginning of World War I, patriotic sentiment was widespread, and extended to many German and Austrian Jews: Zweig, as well as Martin Buber and Hermann Cohen, all showed support. Zweig served in the Archives of the Ministry of War and adopted a pacifist stand like his friend Romain Rolland, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature 1915.

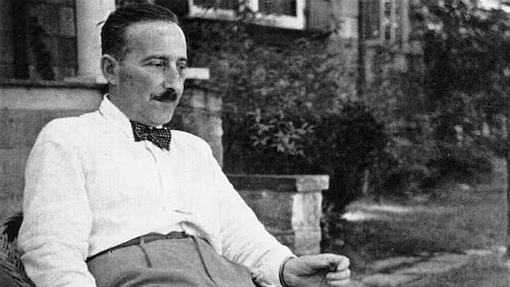

Friderike and Stefan Zweig (1881-1942).

Zweig married Friderike Maria von Winternitz (born Burger) in 1920; they divorced in 1938. As Friderike Zweig she published a book on her former husband after his death. She later also published a picture book on Zweig. In 1939, Zweig married his secretary Lotte Altmann. Zweig’s secretary in Salzburg from November 1919 to March 1938 was Anna Meingast (13 May 1881, Vienna – 17 November 1953, Salzburg).

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) in Salzburg.

In 1934, following Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Zweig left Austria. He lived in England (in London first, then from 1939 in Bath). Because of the swift advance of Hitler’s troops westwards, Zweig and his second wife crossed the Atlantic Ocean and travelled to the United States, where they settled in 1940 in New York City, and travelled.

Richard Strauss, Stefan Zweig and ‘Die schweigsame Frau’ (The Silent Woman)

Since Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier, with only the exception of Intermezzo, all previous operas by Richard Strauss (1864-1949) were based on libretti by Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929), who died in 1929. Stefan Zweig, who was then a celebrated author, had never met Strauss, who was his senior by 17 years. In his autobiography The World of Yesterday, Zweig describes how Strauss got in touch with him after Hofmannsthal’s death to ask him to write a libretto for a new opera. Zweig chose a theme from Ben Jonson.

Strauss was seen as an important icon of German music by the Nazis, who had seized power in Germany in April 1933. Strauss himself was co-operating with the Nazis and became the president of the Reichsmusikkammer in November 1933. Zweig had gotten to know Strauss well through his collaboration and later wrote:

to be co-operative with the national socialists was furthermore of vital interest to him, because in the national socialist sense he was very much in the red. His son had married a Jewess and thus he feared that his grandchildren, whom he loved above all else, would be excluded as scum from the schools; his earlier operas tainted through the half-Jew Hugo von Hofmannstahl; his publisher was a Jew. Therefore, to him it seemed more and more imperative to create support and security for himself, and he did it most perseveringly.

The fact that Zweig was a Jew was causing potential problems for the performance of the opera: in the summer of 1934 the Nazi press began to attack Strauss on this issue. Zweig recounts in his autobiography that Strauss refused to withdraw the opera and even insisted that Zweig’s authorship of the libretto be credited; the first performance in Dresden was authorized by Hitler himself. Subsequent research has shown that Zweig’s account is largely correct. We now know that there was an internal power struggle going on within the Nazi government.

Joseph Goebbels wanted to use Strauss’ international reputation and was willing to relax the rule against works with non-Aryan artists. However, Alfred Rosenberg was more critical of Strauss’ unsoundness on the “Jewish question” and wanted to remove Strauss from his position and replace him with party member Peter Raabe.

Goebbels took the matter to Hitler, who initially ruled in his favor. However, the Gestapo had been intercepting the correspondence between Strauss and Zweig, in which Strauss had been candid about his critical views of the Nazi regime and his role in it. This letter was shown to Hitler, who then changed his mind. The opera was allowed to run for three performances and then banned.

On 6 July 1935, Strauss was visited at his home by a Nazi official sent by Goebbels and told to resign from his position as president of the Reichsmusikkammer on grounds of “ill health,” less than 2 years after he had taken up the post. He was duly replaced by Peter Raabe, who remained in place until the fall of the Nazi regime.

Although banned in Germany, the opera was performed a few times abroad, including Milan, Graz, Prague and Zurich. This would not the first time one of his operas had been banned: Kaiser Wilhelm had banned Feuersnot in 1902. Indeed, the propensity of totalitarian regimes to ban operas was not limited to Germany: a few months later in early 1936 Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was banned by the Soviet regime.

Zweig and Strauss continued to work together secretly (with Joseph Gregor), mainly on the libretto for the opera Friedenstag which was premiered in 1938. The story was almost wholly Zweig’s, but the ideal of pacifism which it embodied was dear to both.

Strauss outlived the Nazi regime by four years and was happy when the opera was revived shortly after the end of the war. He wrote to Joseph Keilberth, the director of the Dresden Opera House where the opera was first revived: “Now, after ten years, the honorable Sir Morosus has been liberated from the concentration camp of the Reichstheaterkammer and has returned to his native town, where twelve years ago I had a lot of trouble to get the name of the librettist on the program”.

Stefan Zweig never heard the opera performed. He had moved from his native Austria to England in 1934 after the Nazis came to power in Germany (although he did visit Austria until the Anschluss in 1938). Soon after the outbreak of war in 1940 he moved to the US and then Brazil. Depressed by the growth of intolerance, authoritarianism, and Nazism, feeling hopeless for the future for humanity, he committed suicide in February 23, 1942.

It was first performed at the Dresden Semperoper on 24-06-1935, conducted by Karl Böhm. After the fall of the Nazi regime, the opera was revived in Dresden (1946) followed by Berlin, München and Wiesbaden.

24-06-1935. Dresden. Semperoper. Premiere of ‘Die schweigsame Frau’ (The Silent Woman) A comic opera in three acts by Richard Strauss (1864-1949) with libretto by Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) after Ben Jonson’s Epicoene, or the Silent Woman.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) crossing the Atlantic on his first trip to Brazil , 1936.

On August 22, 1940, they moved again to Petrópolis, a German-colonized mountain town 68 kilometers north of Rio de Janeiro known for historical reasons as Brazil’s Imperial city. Feeling more and more depressed by the growth of intolerance, authoritarianism, and Nazism, and feeling hopeless for the future for humanity, Zweig wrote a note about his feelings of desperation.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) with his American publisher Ben W. Huebsch (right). Photo: privately owned by Jeffrey B. Berlin. Publication with kind permission.

23-02-1942 the Zweigs were found dead of a barbiturate overdose in their house in the city of Petrópolis, holding hands. He had been despairing at the future of Europe and its culture. “I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labour meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on Earth,” he wrote. The Zweigs’ house in Brazil was later turned into a cultural centre and is now known as Casa Stefan Zweig.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942). Casa Zweig at Petrópolis, near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Work

Zweig was a prominent writer in the 1920s and 1930s, befriending Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud. He was extremely popular in the United States, South America and Europe, and remains so in continental Europe; however, he was largely ignored by the British public.

His fame in America had diminished until the 1990s, when there began an effort on the part of several publishers (notably Pushkin Press, Hesperus Press, and The New York Review of Books) to get Zweig back into print in English. Plunkett Lake Press Ebooks began to publish electronic versions of his non-fiction works. Since that time there has been a marked resurgence and a number of Zweig’s books are back in print.

Critical opinion of his oeuvre is strongly divided between those who despise his literary style as poor, lightweight and superficial, and those who praise his humanism, simplicity and effective style. Michael Hofmann is scathingly dismissive of Zweig’s work, which he dubbed a “vermicular dither”, adding that “Zweig just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing.”

Even the author’s suicide note left Hofmann gripped by “the irritable rise of boredom halfway through it, and the sense that he doesn’t mean it, his heart isn’t in it (not even in his suicide)”.

Zweig is best known for his novellas (notably The Royal Game, Amok, and Letter from an Unknown Woman – which was filmed in 1948 by Max Ophüls), novels (Beware of Pity, Confusion of Feelings, and the posthumously published The Post Office Girl) and biographies (notably Erasmus of Rotterdam, Conqueror of the Seas: The Story of Magellan, and Mary, Queen of Scotland and the Isles and also posthumously published, Balzac).

At one time his works were published without his consent in English under the pseudonym “Stephen Branch” (a translation of his real name) when anti-German sentiment was running high. His biography of Queen Marie-Antoinette was later adapted as a Hollywood movie, starring the actress Norma Shearer in the title role.

Zweig’s autobiography, The World of Yesterday, was completed in 1942 on the day before he committed suicide. It has been widely discussed as a record of “what it meant to be alive between 1881 and 1942” in central Europe; the book has attracted both critical praise and hostile dismissal.

Zweig enjoyed a close association with Richard Strauss, and provided the libretto for Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman). Strauss famously defied the Nazi regime by refusing to sanction the removal of Zweig’s name from the programme for the work’s première on June 24, 1935 in Dresden. As a result, Goebbels refused to attend as planned, and the opera was banned after three performances.

Zweig later collaborated with Joseph Gregor, to provide Strauss with the libretto for one other opera, Daphne, in 1937. At least one other work by Zweig received a musical setting: the pianist and composer Henry Jolles, who like Zweig had fled to Brazil to escape the Nazis, composed a song, “Último poema de Stefan Zweig”, based on “Letztes Gedicht”, which Zweig wrote on the occasion of his 60th birthday in November 1941.

During his stay in Brazil, Zweig wrote Brasilien, Ein Land der Zukunft (Brazil, Land of the Future) which was an accurate analysis of his newly adopted country; in this book he managed to demonstrate a fair understanding of the Brazilian culture that surrounded him.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and Lotte Altmann.

Zweig was a passionate collector of manuscripts. There are important Zweig collections at the British Library and at the State University of New York at Fredonia. The British Library’s Stefan Zweig Collection was donated to the library by his heirs in May 1986. It specialises in autograph music manuscripts, including works by Bach, Haydn, Wagner, and Mahler. It has been described as “one of the world’s greatest collections of autograph manuscripts”.

One particularly precious item is Mozart’s “Verzeichnüß aller meiner Werke” – that is, the composer’s own handwritten thematic catalogue of his works. The 1993–1994 academic year at the College of Europe was named in his honour.

Stefan Zweig and Lotte Altmann suicide

Under examination a collection of newspapers and magazines from 1942, in addition, some Stefan Zweig’s biographies. Stefan and Lotte’s suicide became the official history, nevertheless, 23 discrepancies were found. The newspapers collection was handed down to me by the prestigious psychoanalyst Dr. Jacob Pinheiro Goldberg on February 28, 1999.

The date when the couple was found dead is February 23, 1942, i.e. more than 57 years ago, around six months after settling in Petropolis. Everything seems to have been meticulously planned: the salary of the house employees, some money to be donated, the last legal statement giving destination to their possessions, the last writings to be published, the payment of the rent, instructions on how their clothes should be given away to their employees and to the poor, even the destiny of “Bluchy” the small dog was contrived, it would stay with Mrs. Margarida Banfield ( the proprietor of the house they held under lease).

Several farewell letters were written and put in stamped and addressed envelops. It seems that the preparation for the tragic event took some five or six days.

The last letter, the farewell document, “Declaration” is a hasty apparently non revised note; it was dated February 22, 1942; ( the suicidal attempt allegedly occurred next day). It starts with a statement affirming to be by his own will that he “departs from life”. He was thankful to this magnificent country “Brazil”, for having given him a so warm acceptance. There is no mention whatsoever on the “departure” of his wife and she left no message of her own.

As a reason for his presumptive suicidal gesture, he stated: ” it would be necessary strenuous efforts to reconstruct my life”, a quite unlike reason, being he an worldly acclaimed writer, dominating several languages and carrying the British citizenship.

Also, he mentioned his fatigue for wandering through different countries like a “man lacking nationhood”. It is curious that he left Austria years before he lost his Austrian citizenship, and in reality he was one of the few exiles that could freely choose a new homeland, if he wandered on earth, it was mainly, it seems, for his own choice.

In the newspapers, there was a facsimile of his “Declaration” with a Portuguese translation presenting the strange omission of the last two phrases: “I wish that you all may be able to see again the sunrise after this long night. Too impatiently, I go before this”; he seemed to be referring to the turmoil of that war in course and to his wishful defeat of Nazism. In accord with the press, of March 1, 1942, the author of that suppression was the writer Claudio de Sousa ( a former medical professor of Therapeutics at the Pharmacy School – USP; a “Nazi sympathiser” in accord with a Press editorial of March the 1s t , 1942 – Correio do Povo – Porto Alegre – “Stefan Zweig trusted the defeat of nazism”.

Accusation that Sousa vehemently denied afterwards, even though he had written a couple of years earlier a text called “Our Race” where he made claims about a “Latin race” developed “as a consequence of the Semitic decadence”.

In that text he traced a positive analogy with the race pride of Germans and Austrians ). He was also the friend who phoned at 3 PM to invite Stefan for a walk, shortly thereafter the couple was found dead ( at 4 PM, finally the employees – Antonio and Dulce Moraes – were able to break in the room, through the locked up door ). Later on, giving a statement to the press as a friend of Stefan Zweig, Claudio de Sousa allegedly said: “the suicide had been caused by Zweig’s financial losses in Europe and for the Axis sweeping victories”, what is quite interesting when everyone of Zweig’s personal friends claimed total surprise before the couple’s suicide. Also, Claudio de Sousa took the initiative to call the Presidential Palace, requesting for the burial arrangements.

Stefan and Elisabeth were solemnly buried next day, February the 24th at 4 PM, in Petropolis, at the expenses of the federal government. The previous week, on Sunday, February the 15th, Claudio de Sousa had spent the afternoon with Stefan Zweig, helping him translate from French a reply to a newspaper which had earlier published an unwarranted personal attack against Zweig ( on February the 16th, Stefan Zweig confided all these occurrences to Ernst Feder, a close friend ), the addressee never admitted to have “received” Zweig’s reply, apparently, no copy of this letter was produced anywhere and Claudio de Sousa didn’t confirm the existence of such a document which he allegedly translated from French to Portuguese.

In his biography of Stefan Zweig, Donald Prater mentioned threatening anonymous letters received just some few days before the tragedy.

Anyway, the conclusion in favour of suicide was quite promptly assumed, no official investigation was made and at the funeral, the open casket display in the Petropolis Academy of Letters took place without effective religious interference. (Lotte’s coffin was kept closed merely because her corpse was already putrefying). Even though no document was claimed to be found with a special request dispensing a Jewish cemetery destination.

Notwithstanding, there was a Zweig’s petition to his editor for a simple interment in a Jewish graveyard (apparently found only some time afterwards). Furthermore, Elisabeth was the grand-daughter of a rabbi. By religious insistence there was at the Petropolis cemetery some prayers conducted, being mentioned theological texts authored by Stefan Zweig.

The death certificate had as the informer, Sr. Sady Ferreira Barbosa, apparently an unknown person to Stefan Zweig, and besides the address and city, there is a quite incomplete personal information: “Stephan Zweig ( the name Stefan is produced as Stephan ); male; white; writer; parents: legitimate; married; date of death: February 23, 1942; time: 12:30; cause of death: suicide by ingestion of toxic substance; physician that attested: Dr. Mario M. Pinheiro”.

No necropsy was performed due to instruction that allegedly came from the presidential palace in Petropolis. (on that date and afterwards president Getulio Vargas in his Diary doesn’t even write a word about Stefan Zweig, nevertheless, mentions on February the 28th that the guard of his palace had to receive reinforcements for an expected imminent attack from Nazism adepts; a month before, on January the 28th, Brazil had severed diplomatic relations with the Axis).

There is a first photo presentation of “how they were found”, she was laying in bed by his side. In the second photo presentation, that came up in the press some days later, she was laying upon him, having a left wrist bracelet which was missing in the first photo presentation. The curious first photo presentation had an improbable characteristic, her left hand and fore-arm were floating in space (suggesting “rigor mortis” in a body moved from its original position) showing that this first and finally official photo presentation is quite unlikely. The images brought into view call our attention: Lotte uses a night-gown and Stefan is dressed as if he was ready for a promenade; perhaps they were set for different intents…

There was an inescapable conclusion broadly disseminated: the well informed couple would know by then about the fate of humankind, “Nazism will prevail”. Furthermore, “not even in death, Jews had the courage to assume their cultural or religious identity”. It was largely not in compass with the most courageous public attitude in defence of the exiles, consistently assumed by Stefan Zweig.

In a paper basket there was a discarded and torn document with the statement on the terrible living conditions of Jews in Europe and also that it was not unknown to him that he was considered by the Nazis (Berchtesgaden as a metaphor) their worst intellectual enemy (“the most dangerous Jewish intellectual”), what puzzled him (“Thomas and Heinrich Mann are more meritorious than me…” – “O Globo” February the 24th, 1942). Here comes the most intriguing question, how was he informed about his being considered the Nazis’ worst intellectual enemy? As far as it is known, he was not officially hunted by them.

It is quite a surprise that throughout all these 57 years there remains still unanswered extremely important questions without a convincing explanation. In Petropolis, the only remembrances of Stefan Zweig are the couple’s tomb at the cemetery and the Austrian friends’ plate in his honour at the entrance of his last address, a not open for visitation private residence.

The conductor (Der Dirigent) written by Stefan Zweig in 1910 for the 50th anniversary of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Der Dirigent

Ein goldner Bienenkorb, in dessen Waben

Summend das Volk sich drängt, so scheint

Das Haus mit seinem hingeströmten Licht

Und der Erwartung vieler Menschen, die

In schwärmender Erregung sich versammeln.

Alle Gedanken tasten unablässig

Dort an die dunkle Wand, dahinter sich

In einer Wolke unbestimmter Ahnung

Die Träume bergen.

Unten schäumt der Kessel,

Darin sich die gefährliche Magie

Der Töne braut. Die bunten Stimmen brodeln

In erster Hitze, zucken, sieden, spritzen

Schon manchmal eine kleine Melodie

Wie Schaum herauf. Allein sie zittert schwank

Im hohen Raum und stürzt dann wie zerbrochen

Zurück ins Ungefähr der andern Stimmen.

Und plötzlich wo ein Klang: das Licht verlischt,

Der Ring des Raums zerrinnt ins Grenzenlose,

Nacht stürzt herab, und alles wird Musik.

(— Denn sie, im Unbegrenzten heimisch schweifend,

Gibt schamhaft ihre körperlose Seele

Denn Blicken nicht und ausgestreckten Händen:

Urschwesterlich sind Dunkel und Musik.)

Und was vordem im ausgesparten Raume

An zagen Stimmen suchend rang, was sich

Noch scheu und ganz vereinzelt erst versuchte,

Das greift jetzt ineinander, flutet über,

Meer wird es, Meer, das seine Wellen bald

Wie Knabenhaar verliebt und eitel kräuselt,

Bald sie wie Fäuste ballt, ein Meer,

Das auf zu Sternen will. Nun sprengt es hoch

Bis ans Gebälk die farblos heiße Gischt

Der Töne, wirft sie gegen unser Herz,

Das sich noch weigert (denn wer gibt sich gern

An ein gefährlich unbekannt Gefühl

Ganz ohne Zagen hin?) Allein es reißt

Gewaltsam mit in seine blinde Kraft,

Und Flut sind wir mit ihm, nur wesenlos

Verströmte Flut, die bald zum Wogenkamm

Des seligsten Entzückens hochgeschleudert

In weißen Schäumen funkelnd sich zersprüht,

Bald wie begraben in der jähen Trauer

Des Niederstürzens ins smaragdne Dunkel.

Wir alle, sonst vieltausendfach zerstückt

Durch Zufall, Schicksal und geheime Neigung,

Sind eine Welle zitternder Entzückung,

Drin unser eigen Leben unbewußt

Und ohne Atem, ohne Willen flutet,

Ertrunken in den Tönen.

Aber dort,

Hoch über diesem Meer, schwebt einer noch,

Wie eine schwarze Möwe mit den Schwingen

Hinreisend über das erregte Stürmen

Des namenlos beseelten Elements.

Er ringt damit, taucht bald hinab, als griff

Er Perlen von dem Grund, bald schnellt er hoch

Wie ein Delphin sich aus dem wildgepeitschten

Gewirr der brennend lodernden Musik.

Ein Einziger, da wir schon hingerissen

Und schwank verströmt sind, selber Wind und Welle,

Kämpft er noch mit den losen Elementen,

Gebändigt halb und halb der Töne Meister. —

Der Stab in seiner Hand (ist er der gleiche,

Mit dem einst Prospero den grausen Sturm

Hinwetternd auf die Insel warf?)

Scheint, ein Magnet, das fließend Erz der Töne

Hinaufzuzwingen in die starke Hand,

Und all die Wellen, drin wir uns verbluten,

Strömen ihm zu, dem roten Herz, drin

Die Unruh Rhythmus wird, das wirre Leben

Der Elemente klare Melodie.

Wer ist der Zauberer, wer? Mit einem Wink

Hat er des Vorhangs harte Nacht gespalten.

Sie rauscht hinweg. Und hinter ihr sind Träume

Mit blauem Himmel, aufgeblühten Sternen,

Mit Duft und Wind und Bildern wie von Menschen.

Nein, nein! Mit Menschen! Denn kaum hat er jetzt

Die Hand gehoben, so bricht diesem schon,

Den er bedeutet, Stimme aus der Wunde

Der aufgerißnen Brust, und jetzt den andern!

Sie atmen Leid und Lust. Und alles ist,

Wie er gebietet. Seht, die Sterne löschen

Jetzt mählich aus, die Wolkenzüge brennen

Vom Feuerhauch der neuen Dämmerung,

Und Sonne naht und mit ihr andre Träume.

Und über all dies schüttet er Musik,

Die er von unten aus dem unsichtbaren

Geström mit seinen losen Händen schöpft.

Tag wird aus Nacht. Womit hat er Gewalt,

Daß ihm die Töne dienen, Menschen sich

Ausbluten im Gesang und daß wir alle

Hier leise atmend wie im unruhvoll

Erregten Schlafe sind, vom süßen Gift

Des Klangs betäubt? Und daß ich immer

Das Zucken seiner Hand so spüren muß,

Als riß er eine angespannte Saite

In meiner Brust entzwei?

Wohin, wohin

Treibt er uns fort? Wir gleiten nur wie leise

Barken des Traums auf niegesehnen Wassern

Ins Dunkel weiter. Goldene Sirenen

Neigen sich manchmal über unsre Stirnen,

Doch er lenkt weiter, steil das Steuer in

Die feste Faust gepreßt. Wir gleiten, gleiten

Zu stillen Inseln, sturmzerrißnen Wäldern.

Wer weiß, wie lang? Sind’s Stunden, Tage,

Ist es ein Jahr?

Da sinkt der Vorhang zu.

Die Barke hält. Wir wachen wie verschreckt

In unsre Wirklichkeit. Doch er, wo ist

Er hin, in dessen Händen wir gewesen,

Der dorten stand, ein unbewegter Stern

Über dem Aufschwall geisternder Gewässer?

Hat ihn die Flut, die er bezwang, nun doch

Hinabgerissen in ihr Dunkel? — Nein!

Dort stirbt ein Schatten weg. Der heiße Blick

Greift rasch ihm nach. Doch ringsum schwillt

Schon Unruh und Geräusch, die Menge bricht

In tausend Stücke, einzelne Gesichter,

Zerrinnt in Worte, die sich laut verbreitern,

Der Jubel dröhnt! Aufflammen alle Lichter, —

Wir sind am Strand, daran die Träume scheitern.

Last note

In 1942 Stefan Zweig left a note which ends with the following sentences: “Greetings to all my friends! May they still see the first gleam of dawn after the long night. All too impatient, I am going ahead of them!”

Bibliography

The dates mentioned below are the dates of first publication in German.

Fiction

- Forgotten Dreams, 1900 (Original title: Vergessene Träume).

- Spring in the Prater, 1900 (Original title: Praterfrühling).

- A Loser, 1901 (Original title: Ein Verbummelter).

- In the Snow, 1901 (Original title: Im Schnee).

- Two Lonely Souls, 1901 (Original title: Zwei Einsame).

- The Miracles of Life, 1903 (Original title: Die Wunder des Lebens).

- The Love of Erika Ewald, 1904 (Original title: Die Liebe der Erika Ewald).

- The Star Over the Forest, 1904 (Original title: Der Stern über dem Walde).

- The Fowler Snared, 1906 (Original title: Sommernovellette).

- The Governess, 1907 (Original title: Die Governante).

- Scarlet Fever, 1908 (Original title: Scharlach).

- Twilight, 1910 (Original title: Geschichte eines Unterganges).

- A Story Told In Twilight, 1911 (Original title: Geschichte in der Dämmerung).

- Burning Secret, 1913 (Original title: Brennendes Geheimnis).

- Fear, 1920 (Original title: Angst).

- Compulsion, 1920 (Original title: Der Zwang).

- The Eyes of My Brother, Forever, 1922 (Original title: Die Augen des ewigen Bruders).

- Fantastic Night, 1922 (Original title: Phantastische Nacht).

- Letter from an Unknown Woman, 1922 (Original title: Brief einer Unbekannten).

- Moonbeam Alley, 1922 (Original title: Die Mondscheingasse).

- Amok, 1922 (Original title: Amok) – novella, initially published with several others in Amok. Novellen einer Leidenschaft.

- The Invisible Collection, 1925 (Original title: Die unsichtbare Sammlung).

- Downfall of the Heart, 1927 (Original title: Untergang eines Herzens”).

- The Invisible Collection see Collected Stories below, (Original title: Die Unsichtbare Sammlung, first published in book form in ‘Insel-Almanach auf das Jahr 1927’).

- The Refugee, 1927 (Original title: Der Flüchtling. Episode vom Genfer See).

- Confusion of Feelings or Confusion: The Private Papers of Privy Councillor R. Von D, 1927 (Original title: Verwirrung der Gefühle) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen.

- Twenty-Four Hours in the Life of a Woman, 1927 (Original title: Vierundzwanzig Stunden aus dem Leben einer Frau) – novella initially published in the volume Verwirrung der Gefühle: Drei Novellen.

- Buchmendel, 1929 (Original title: Buchmendel).

- Short stories, 1930 (Original title: Kleine Chronik. Vier Erzählungen) – includes Buchmendel.

- Did He Do It?, published between 1935 and 1940 (Original title: War er es?).

- Leporella, 1935 (Original title: Leporella).

- Collected Stories, 1936 (Original title: Gesammelte Erzählungen) – two volumes of short stories:

- The Chains (Original title: Die Kette);

- Kaleidoscope (Original title: Kaleidoskop). Includes: Casual Knowledge of a Craft, Leporella, Fear, Burning Secret, Summer Novella, The Governess, Buchmendel, The Refugee, The Invisible Collection, Fantastic Night and Moonbeam Alley.

- Incident on Lake Geneva, 1936 (Original title: Episode an Genfer See Revised version of “Der Flüchtung. Episode vom Genfer See” published in 1927).

- The Buried Candelabrum, 1936.

- Beware of Pity, 1939 (Original title: Ungeduld des Herzens) novel.

- The Royal Game or Chess Story or Chess (Original title: Schachnovelle; Buenos Aires, 1942) – novella written in 1938–41.

- Journey into the Past, 1976 (Original title: Widerstand der Wirklichkeit).

- Clarissa, 1981 unfinished novel.

- The Debt Paid Late, 1982 (Original title: Die spät bezahlte Schuld).

- The Post Office Girl, 1982 (Original title: Rausch der Verwandlung. Roman aus dem Nachlaß; The Intoxication of Metamorphosis).

Biographies and historical texts

- Béatrice Gonzalés-Vangell, Kaddish et Renaissance, La Shoah dans les romans viennois de Schindel, Menasse et Rabinovici, Septentrion, Valenciennes, 2005, 348 pages.

- Emile Verhaeren, 1910.

- Three Masters: Balzac, Dickens, Dostoeffsky, 1920 (Original title: Drei Meister. Balzac – Dickens – Dostojewski. Translated into English by Eden and Cedar Paul and published in 1930 as Three Masters).

- Romain Rolland. The Man and His Works, 1921 (Original title: Romain Rolland. Der Mann und das Werk).

- Nietzsche, 1925 (Originally published in the volume titled: Der Kampf mit dem Dämon. Hölderlin – Kleist – Nietzsche).

- Decisive Moments in History, 1927 (Original title: Sternstunden der Menschheit. Translated into English and published in 1940 as The Tide of Fortune: Twelve Historical Miniatures).

- Adepts in Self-Portraiture: Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy, 1928 (Original title: Drei Dichter ihres Lebens. Casanova – Stendhal – Tolstoi).

- Joseph Fouché, 1929 (Original title: Joseph Fouché. Bildnis eines politischen Menschen) Now available as an electronic book.

- Mental Healers: Franz Mesmer, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud, 1932 (Original title: Die Heilung durch den Geist. Mesmer, Mary Baker-Eddy, Freud) Now available as an electronic book.

- Marie Antoinette: The Portrait of an Average Woman, 1932 (Original title: Marie Antoinette. Bildnis eines mittleren Charakters) ISBN 4-87187-855-4.

- Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1934 (Original title: Triumph und Tragik des Erasmus von Rotterdam).

- Maria Stuart ISBN 4-87187-858-9.

- The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin, 1936 (Original title: Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt).

- Conqueror of the Seas: The Story of Magellan, 1938 (Original title: Magellan. Der Mann und seine Tat) ISBN 4-87187-856-2.

- Amerigo, 1942 (Original title: Amerigo. Geschichte eines historischen Irrtums) – written in 1942, published the day before he died ISBN 4-87187-857-0.

- Balzac, 1946 – written, as Richard Friedenthal (de) describes in a postscript, by Zweig in the Brazilian summer capital of Petrópolis, without access to the files, notebooks, lists, tables, editions and monographs that Zweig accumulated for many years and that he took with him to Bath, but that he left behind when he went to America. Friedenthal wrote that Balzac “was to be his magnum opus, and he had been working at it for ten years. It was to be a summing up of his own experience as an author and of what life had taught him.” Friedenthal claimed that “The book had been finished”, though not every chapter was complete; he used a working copy of the manuscript Zweig left behind him to apply “the finishing touches”, and Friedenthal rewrote the final chapters (Balzac, translated by William and Dorothy Rose [New York: Viking, 1946], pp. 399, 402).

Plays

- Tersites, 1907 (Original title: Tersites).

- Das Haus am Meer, 1912.

- Jeremiah, 1917 (Original title: Jeremias).

Other

- The World of Yesterday (Original title: Die Welt von Gestern; Stockholm, 1942) – autobiography.

- Brazil, Land of the Future (Original title: Brasilien. Ein Land der Zukunft; Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1941).

- Journeys (Original title: Auf Reisen; Zurich, 1976); collection of essays.

Letters

- Stefan and Lotte Zweig’s South American Letters 1940-1942: Darién J. Davis; Oliver Marshall, eds. (2010). New York, Argentina and Brazil. New York, Continuum. ISBN 1441107126. A German translation of this book appeared for the first time in January 2017: Stefan und Lotte Zweigs Südamerikanische Briefe. Hg. von Darién J. Davis und Oliver Marshall. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2017, 336 pages.

- The Correspondence of Stefan Zweig with Raoul Auernheimer and with Richard Beer-Hofmann (1866-1945), ed. Jeffrey B. Berlin and Donald G. Daviau. Vol. 20. Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture (Columbia, South Carolina: Camden House 1983), 273 p.

- Stefan Zweig: Briefwechsel mit Hermann Bahr (1863-1934), Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) und Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), hrsg. von Jeffrey B. Berlin, H. Lindken u. Donald A. Prater (Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer Verlag 1987), 526 p.

- Stefan Zweig: Briefe 1897-1942, hrsg. von Knut Beck und Jeffrey B. Berlin, 4 Bde. (Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer Verlag 1995-2005).

- Vol. I Briefe 1897-1914 (1995) = 589 p.

- Vol. II Briefe 1914-1919 (1998) = 665 p.

- Vol. III Briefe 1920-1931 (2000) = 725 p.

- Vol. IV Briefe 1932-1942 (2005) = 882 p.

- Stefan Zweig – Friderike Zweig. “Wenn einen Augenblick die Wolken weichen.” Briefwechsel 1912-1942, hrsg. von Jeffrey B. Berlin und Gert Kerschbaumer (Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer Verlag 2006), 448 p.

Adaptations

- Artist Jeff Gabel created an English-language adaptation of Vierundzwanzig Stunden aus dem Leben einer Frau in a large-scale comic book format in 2004, titled 24 Hours in the Life of a Woman.

- An adaptation by Stephen Wyatt of Beware of Pity was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in 2011.

- The 2013 French film A Promise (Une promesse) is based on Zweig’s novella Journey into the Past (Reise in die Vergangenheit).

- The 2013 Swiss film Mary Queen of Scots directed by Thomas Imbach is based on Zweig’s Maria Stuart.

- The end-credits for Wes Anderson’s 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel say that the film was inspired in part by Zweig’s novels. Anderson said that he had “stolen” from Zweig’s novels Beware of Pity and The Post-Office Girl in writing the film, and it features actors Tom Wilkinson as The Author, a character based loosely on Zweig, and Jude Law as his younger, idealised self seen in flashbacks. Anderson also said that the film’s protagonist, the concierge Gustave H., played by Ralph Fiennes, was based on Zweig. In the film’s opening sequence, a teenaged girl visits a shrine for The Author, which includes a bust of him wearing Zweig-like spectacles and celebrated as his country’s “National Treasure”.