1910. Max Reger (1873-1916).

- Profession: composer, conductor, pianist

- Relation to Mahler: No evidence of direct contact, attended 1910 Concert Munich 12-09-1910 – Symphony No. 8 (Premiere)

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 19-03-1873 Brand, Germany (Bavaria)

- Died: 11-05-1916 Leipzig, Germany. Aged 43.

- Buried:

- Jena (1916-1922): 14-05-1916. After the remembrance-service and cremation, his remains became part of the “Altar” of Elsa Reger in the house in Jena. She maintained a sort of Reger-Altar. 14-05-1916 was described in more or less detail in various sources (Fritz Stein 1939: p.78-79; Elsa Reger 1930: p.155-156). Although Reger was cremated, which was relatively new in those days, the clergy did not object.

- Weimar (1922-1930).

- Munchen (1930-present): Josef Weiss designed the gravestone in Munchen. Forest cemetery, Waldfriedhof, Munich, Germany. When his wife moved to Munich she had his urn buried at the Waldfriedhof.

Attended 1910 Concert Munich 12-09-1910 – Symphony No. 8 (Premiere).

Johann Baptist Joseph Maximilian Reger, commonly known as Max Reger, was a German composer, pianist, organist, conductor, and academic teacher. He worked as a concert pianist, as a musical director at the Leipzig University Church, as a professor at the Royal Conservatory in Leipzig, and as a music director at the court of Duke Georg II of Saxe-Meiningen.

Reger first composed mainly Lieder, chamber music, choral music and works for piano and organ. He later turned to orchestral compositions, such as the popular Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Mozart, and to works for choir and orchestra such as Gesang der Verklärten (1903), Der 100. Psalm (1909), Der Einsiedler and the Hebbel Requiem (both 1915).

Born in Brand, Bavaria, Reger studied music theory in Sondershausen, then piano and theory in Wiesbaden. The first compositions to which he assigned opus numbers were chamber music and Lieder. A concert pianist himself, he composed works for both piano and organ. His first work for choir and piano to which he assigned an opus number was Drei Chöre.

Reger returned to his parental home in 1898, where he composed his first work for choir and orchestra, Hymne an den Gesang (Hymn to singing), Op. 21. From 1899, he courted Elsa von Bercken who first rejected him. He composed many songs such as Sechs Lieder, Op. 35, on love poems by five authors.

Reger moved to Munich in September 1901, where he obtained concert offers and where his rapid rise to fame began. During his first Munich season, Reger appeared in ten concerts as an organist, chamber pianist and accompanist. Income from publishers, concerts and private teaching enabled him to marry in 1902. Because his wife Elsa was a divorced Protestant, he was excommunicated from the Catholic Church. He continued to compose without interruption, for example Gesang der Verklärten, Op. 71.

In 1907, Reger was appointed musical director at the Leipzig University Church, a position he held until 1908, and professor at the Royal Conservatory in Leipzig. In 1908 he began to compose Der 100. Psalm (The 100th Psalm), Op. 106, a setting of Psalm 100 for mixed choir and orchestra, for the 350th anniversary of Jena University. Part I was premiered on 31 July that year. Reger completed the composition in 1909, premiered in 1910 simultaneously in both Chemnitz and Breslau.

In 1911 Reger was appointed Hofkapellmeister (music director) at the court of Duke Georg II of Saxe-Meiningen, responsible also for music at the Meiningen Court Theatre. He retained his master class at the Leipzig conservatory.

1913. Max Reger (1873-1916) in a recording session at Welte-Mignon (Leipzig).

In 1913 he composed four tone poems on paintings by Arnold Böcklin (Vier Tongedichte nach Arnold Böcklin), including Die Toteninsel (Isle of the Dead), as his Op. 128. He gave up the court position in 1914 for health reasons.

In response to World War I, he thought in 1914 already to compose a choral work to commemorate the fallen of the war. He began to set the Latin Requiem but abandoned the work as a fragment. He composed eight motets forming Acht geistliche Gesänge für gemischten Chor (Eight Sacred Songs), Op. 138, as a master of “new simplicity”. In 1915 he moved to Jena, commuting once a week to teach in Leipzig. He composed in Jena the Hebbel Requiem for soloist, choir and orchestra. Reger died of a heart attack while staying at a hotel in Leipzig on 11 May 1916. The proofs of Acht geistliche Gesänge, including “Der Mensch lebt und bestehet nur eine kleine Zeit”, were found next to his bed.

Reger had also been active internationally as a conductor and pianist. Among his students were Joseph Haas, Sándor Jemnitz, Jaroslav Kvapil, Ruben Liljefors, Rudolf Serkin, George Szell and Cristòfor Taltabull.

Reger was the cousin of Hans Kossler (1853-1926).

Reger produced an enormous output in just over 25 years, nearly always in abstract forms. Few of his compositions are well known in the 21st century. Many of his works are fugues or in variation form, including what is probably his best-known orchestral work, the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Mozart based on the opening theme of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331.

Reger wrote a large amount of music for organ, the most popular being his Fantasy and Fugue on BACH, Op. 46 and the Toccata and Fugue in D minor from the collection Op. 129. While a student under Hugo Riemann in Wiesbaden, Reger met the German organist, Karl Straube; they became friends and Straube premiered many of Reger’s organ works, such as the Three chorale fantasias, Op. 52. Reger recorded some of his works on the Welte Philharmonic organ, including excerpt from 52 Chorale Preludes, Op. 67.

Reger was particularly attracted to the fugal form and created music in almost every genre, save for opera and the symphony (he did, however, compose a Sinfonietta, his op. 90). A similarly firm supporter of absolute music, he saw himself as being part of the tradition of Beethoven and Brahms. His work often combined the classical structures of these composers with the extended harmonies of Liszt and Wagner, to which he added the complex counterpoint of Bach. Reger’s organ music, though also influenced by Liszt, was provoked by that tradition.

Some of the works for solo string instruments turn up often on recordings, though less regularly in recitals. His solo piano and two-piano music places him as a successor to Brahms in the central German tradition. He pursued intensively Brahms’s continuous development and free modulation, whilst being rooted in Bach-influenced polyphony.

Reger was a prolific writer of vocal works, Lieder, works for mixed chorus, men’s chorus and female chorus, and extended choral works with orchestra such as Der 100. Psalm and Requiem, a setting of a poem by Friedrich Hebbel, which Reger dedicated to the soldiers of World War I. He composed music to texts by poets such as Gabriele D’Annunzio, Otto Julius Bierbaum, Adelbert von Chamisso, Joseph von Eichendorff, Emanuel Geibel, Friedrich Hebbel, Nikolaus Lenau, Detlev von Liliencron, Friedrich Ruckert (1788-1866) and Ludwig Uhland. Reger assigned opus numbers to major works himself.

His works could be considered retrospective as they followed classical and baroque compositional techniques such as fugue and continuo. The influence of the latter can be heard in his chamber works which are deeply reflective and unconventional.

In 1898 Caesar Hochstetter, an arranger, composer and critic, published an article entitled “Noch einmal Max Reger” in a music magazine (Die redenden Künste 5 no. 49, pp. 943 f). Caesar recommended Reger as “a highly talented young composer” to the publishers. Reger thanked Hochstetter with the dedications of his piano pieces Aquarellen, Op. 25, and Cinq Pièces pittoresques, Op. 34.

Reger had an acrimonious relationship with Rudolf Louis, the music critic of the Münchener Neueste Nachrichten, who usually had negative opinions of his compositions. After the first performance of the Sinfonietta in A major, Op. 90, on 2 February 1906, Louis wrote a typically negative review on 7 February. Reger wrote back to him: “Ich sitze in dem kleinsten Zimmer in meinem Hause. Ich habe Ihre Kritik vor mir. Im nächsten Augenblick wird sie hinter mir sein!” (“I am sitting in the smallest room of my house. I have your review before me. In a moment it will be behind me!”).

Private life

Composer, Conductor, Pianist. Born Johann Baptist Joseph Maximilian Reger in Brand, Bavaria. He grew up in the nearby town of Weiden, to where his family had moved a year after his birth. He studied at the local school where his father worked as a teacher. He received his earliest training in harmony and piano from his parents before meeting Adalbert Lindner, who is an organist in Weiden and one of his fathers former students. Linder recognizes his talents and recomments him to the great organ teacher Hugo Riemann.

In April of 1890 he left home to study with Riemann at the Sondershausen Conservatory, even changing schools when Riemann left Sondershausen for the Wiesbaden Conservatory in April 1891. In October 1896 he joined the military as a one-year volunteer. Heavily in debt and in poor health, due to an ulcer at the neck he is released after a year. In consequence of his military service and professional setbacks, he suffers a nervous and physical breakdown and returns to her parents house back in 1898. In Weiden his productivity increases enormously and he can persuade his family to move to Munich.

In 1902 he marries Elsa von Bercken a divorced protestant, which results in his excommunication. In 1905 he followed Joseph Rheinberger as a professor of counterpoint at Royal Academy of the Art of Music in Munich, but due disagreements with the predominantly conservative faculty he leaves after only one year.

In the following year he’s appointed music director at the University of Leipzig and conductor of the University Choir St. Pauli. Although he resigned his post as director and conductor after a year, he continued teaching composition there for the rest of his life. Duke Georg II von Sachsen-Meiningen appoints him court conductor in Meiningen in 1911.

Due to overwork and his continued abuse of alcohol he breaks down in 02-1914 during a concert in Hagen. He is forced to cancel all concerts of the tour and gives up the position as court conductor. The family moves to Jena from where he travels every other week to Leipzig to teach his class and meet friends.

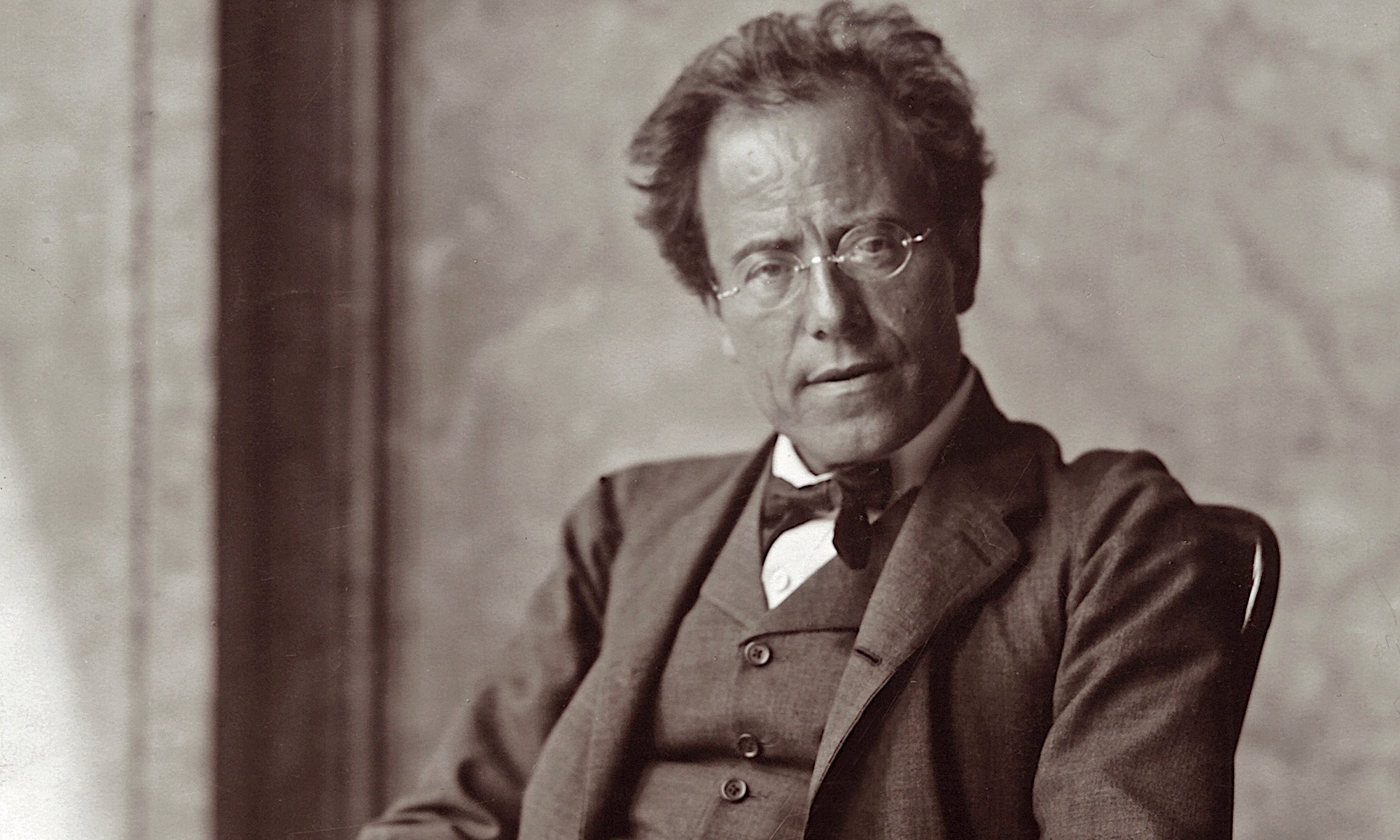

The photo above is one of the last photos of Max Reger. It was taken in Stuttgart by Kammermusiker Franz Klein on 10-02-1916 (Dr. J.Schaarwächter of the Max-Reger-Institut Karlsruhe was so kind as to provide this information). Three months afterward, Reger was dead.

On 10-05-1916 he taught his class at the conservatory and then had dinner with Henri Hinrichsen (1868-1942). During the night he suffered a heart attack in his Hotel.

After his death

He repeatedly uttered the wish to be buried at the coast of the Baltic Sea, near Kolberg. It did not happen.

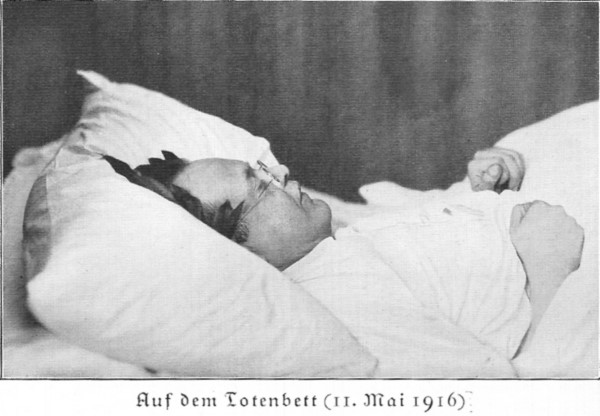

Reger on his deathbed

It is probably a reflection of the shock that went through musical Germany in 1916 that a photo of Reger on his deathbed (made by Hoenisch) was published. But then, Reger himself treasured a photo of Johannes Brahms on his deathbed. On the photo is visible that a laurel-wreath was placed on his head as a sign of honour. His hands seem folded, this is because Reger died while reading a newspaper. Adolf Wach, after paying honour to Max Reger wrote on 11-05-1916 to Fritz Stein: “welch ein schöpferische Kraft ist da erloschen”.

1916. Max Reger (1873-1916).

Elsa Reger, in her book (1930), writes in some detail about the circumstances surrounding Reger’s death. She arrived in the afternoon of May 11, 1916 at the death-bed of her beloved husband (p. 153) and stayed the whole night (p. 154), meaning until May 12. She also writes that on that morning, as Max Klinger (1857-1920) made the drawing of Reger (original in Leipzig Museum der bildende Kunste) she saw her husband for the last time. The drawing, reads “11. Mai 1916”, referring here obviously to the day Reger died and not to the day Klinger made the drawing.

1916. Max Reger (1873-1916) by Max Klinger (1857-1920).

There exist two slightly differing versions of Klinger’s drawing. Opitz (2000: p. 157) indeed mentiones “Zeichnungen” (drawings) and also Popp & Shigihara (eds.) in “Auf der Suche nach dem Werk” (1998: 217) mention the existence of originally two drawings. The topmost drawing was reproduced not only in Elsa Reger (1930: facing p. 192) but also in Müller von Asow (1944: Tafel 73) (compare Popp & Shigihara ibid.).

Two deathmasks

Two deathmasks were made. This is not much reflected upon in the Reger-literature (Fritz Stein (1939, p.78) mentions only that Engelmann modelled Reger’s hands). But it did not escape the attention of scientific Reger-research: Opitz (2000: p. 151) discusses the two death-masks and the date when they were made. The doubt thereabouts mainly originates from two different statements by K. Dittmar from 1933 resp. 1937.

1. Richard Engelman

Richard Engelmann writes (in: Ernst Benkard: Das ewige Antlitz (2nd Ed., 1927), page 50, nr. 93) about the deathmask he made, that he took it in the presence of Elsa Reger and also modelled the hands of Reger (photo in: Müller von Asow 1944: Tafel 74). NB: the first Edition of Benkard (1926) cites Engelmann in a slightly different way. An interesting detail he mentiones is that he (Engelmann) visited Max Klinger early in the morning, heard about Reger’s death and then immediately went to the Hotel, where Elsa Reger was already present. As she arrived only in the afternoon of May 11 in Leipzig (see above) and this took place in the morning it follows that Engelmann made the death-mask on the 12th and not on May 11, 1916 as he (Engelmann) himself mentiones. Indeed, the specimen of the Meininger Museen is marked with “12. 05. 1916”. Opitz (2000: p. 151, note 34) also refers to a publication of K. Dittmar (1937) who, citing Elsa Reger, positiones the Engelmann-mask as the second one, made 24 hours after the one by Seffner.

2 Carl Seffner

Carl Seffner is well-known for his using Bach’s original skull to reconstruct his face. Reger had been vey upset about this dishonour done to the remains of the composer he most admired. A little twist of irony it is that Seffner modelled also Reger’s death-mask. Reger’s first biograph, Max Hehemann writes (1917, facing page 112): “Die Maske ist wenige Stunden nach Eintritt des Todes aufgenommen und gibt daher noch den Eindruck des Lebens” (The mask was taken a few hours after death and so gives a lifelike impression).

As it can be assumed now that Engelmann modeled his mask on May 12, 1916 and Seffner’s was made 24 hours earlier (see also the discussion in Opitz 2000: p. 151, note 34) it can be assumed that Seffner made the first death-mask on May 11, 1916.

The death-mask of Seffner raises in itself also a question: how does it really look like? The photo of this death-mask as pictured in Mueller von Asow (1944) and Opitz (2000) is very different from the photo’s in Hehemann (1917) and Stein (1956: fig. 123).

As Opitz (2000: p. 163, fig. 6) and Mueller von Asow (1944: Tafel 74) both present the same Seffner-mask, the death-mask as depicted in Hehemann (1917) and Stein (1956: fig. 123) must be an extended version made by Seffner which was based on the original death-mask. This version reflects much more the photo by Hoenisch of Reger on his deathbed.

However, the most beautiful photo of Seffner’s Reger-death-mask was published in Rosemarie Clausen: Die Vollendeten (Tazzelwurm Verlag Albert Jauß, Stuttgart 1941).

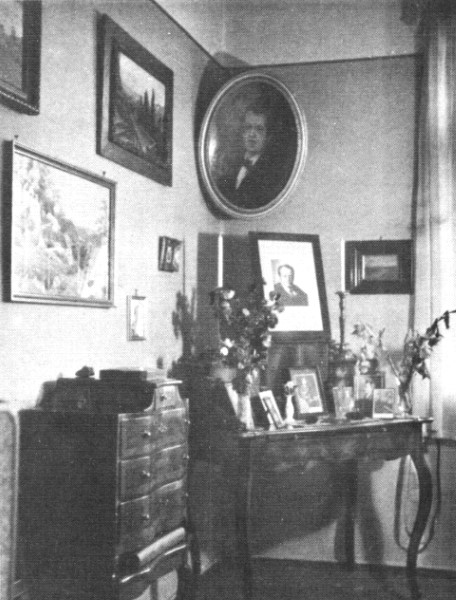

1916-1922. Max Reger (1873-1916) altar. After the remembrance-service and cremation, his remains became part of the “Altar” of Elsa Reger in her house in Jena.