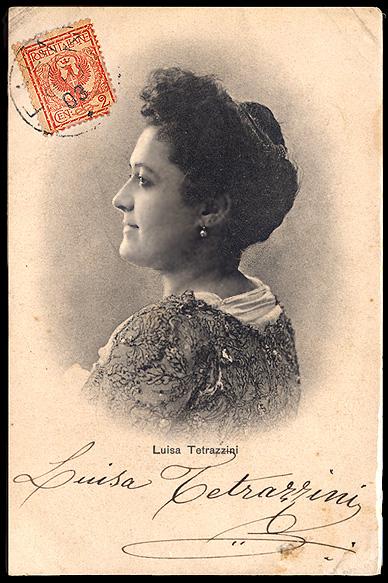

- Profession: Soprano.

- Residences: Florence, London, New York.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 29-06-1871 Florence, Italy.

- Died: 28-04-1940 Milan, Italy.

- Buried: Tetrazzini’s mausoleum is demolished, the remains were transferred to a cemetery for the poor. Funds had not been forthcoming to maintain her mausoleum, so it had fallen into disrepair.

Born in Florence, she first studied with her sister (the soprano Eva Tetrazzini), then with Contrucci and Ceccherini before her début at the Pagliano in Florence as Inès in L’Africana (1890). Tetrazzini then sang at the Argentina in Rome before she began an extensive series of appearances in the Italian provinces, Eastern Europe, South America, Spain and Mexico in the years between 1891 and 1906. She then managed to sneak past Nellie Melba’s guard and made a sensation at Covent Garden (1907) as Violetta, and returned to London each season till 1912. There, she was well liked as Gilda, Lucia, Amina, Marguerite de Valois in Les Huguenots and a handful of other roles.

Debuted in Florence, Italy, as Inéz (1890); debuted in U.S. in San Francisco (1907), in Covent Garden, London (1907); with Enrico Caruso, published The Art of Singing (1909); published autobiography, My Life of Song (1921); published How To Sing (1923); sang farewell concert (1933). Coloratura soprano Luisa Tetrazzini enjoyed a long career as an international opera star. She was born in 1871 into a family of Florentine musicians; her father, a military tailor, provided well for his children and had them tutored in music and singing.

After appearances in Spain, Portugal, Russia, and Latin America, she made her debut in the United States at San Francisco in 1904 and her London debut in 1907. She sang with the Manhattan Opera Company (1908–10), afterward appearing with the Metropolitan Opera Company (1911–12) and the Chicago Opera Company. She continued her concert career until 1931. Her sensational success was due to her brilliant high tones and her agility in coloratura work. She wrote two books, My Life of Song (1921) and How to Sing (1923).

At the Metropolitan in New York, management made the seemingly impossible mistake (in more ways than one) of letting Tetrazzini slip through their fingers and into the hands of Oscar Hammerstein at the Manhattan Opera. At the latter house, beginning in 1908, she was the toast of New York in her London repertoire and as Lakmé, Dinorah, Elvira in I Puritani and other new interpretations. Tetrazzini eventually did sing at the Met, very briefly, making only eight appearances there as Lucia, Gilda and Violetta during the 1911 – 12 season. She also sang with the Boston and Chicago companies (1911 – 1914), but thereafter confined herself primarily to recitals and concert appearances. These she was obliged to continue well past her prime (the last was in London, 1934), since three husbands had helped to totally deplete the vast fortunes she had earned in her heyday. She consoled herself with seances, at which she claimed to have communicated with the spirits of Adelina Patti, Caruso and Tamagno. By the time of her death in Milan, there was no money left at all.

If the little pearl of wisdom “It ain’t over till the fat lady sings” bore any truth whatsoever, the curtain would have fallen as soon as Luisa Tetrazzini opened her mouth, or even set foot on the stage for that matter. Heftier than the heftiest of her compatriots, here was a truly “Rubenesque,” robust prima donna from the days of yore, plump as a spring robin, but possessed of a lovely coloratura no feathered songbird could have matched. She was also witty and good-natured, with a flair for fun that made her splendid in comedic roles.

Luisa Tetrazzini was truly an opera “star” of international proportions, with an almost unflawed coloratura. She had a highly polished mastery of her art, with a sensational command of the most difficult and florid music ever composed for her type of voice. Her voice rang out brilliantly and firmly, except for occasional lapses in the lower ranges which critics always made a point of taking note. Any modern day soprano might learn volumes by taking the time to study even a handful of her recordings.

Fortunately, Tetrazzini made many recordings, and her voice seems to have taken well to the primitive techniques available in her day. It is probably fair to assume that we are left with an accurate sonic preservation of her voice, for her records confirm the finer aspects of her singing (and many times that problem area in the middle and lower ranges) of which contemporary critics wrote so admirably.

Her operatic and song repertoires are well represented on discs, so that we may today enjoy a versatile assortment of her artistry. Sometimes her earlier recordings are occasionally sloppy, as if the idea were to get her voice on as many discs as possible – as quickly as possible, and they were issued mistakes and all. But this matter loses importance when a larger sampling of her recordings is evaluated. Time and again, in excerpts from the coloratura soprano repertoire, she displays an amazing ability to attack the most soaring high notes dead center, hold them firmly and assuredly, seemingly with no effort at all, till she lets them melt away to a whisper. Somehow, the early recording processes vividly capture all of this.

The best of the best can be described, but they need to be heard to be believed. Her renditions of “Sempre libera” and “Una voce poco fa” are musts. In these and a large number of other operatic excerpts, her display of breath control is astounding. She is dramatically thrilling in many recordings, while almost nonchalantly racing up and down scales. Her ability to deliver perfect staccato (even when repeating high Ds), the ease in which she could sing E flat in alt, drop an octave or so and then return in one seamless column of sound is overwhelming to hear. And the obligatory high C’s so near and dear to the soprano-lovers’ hearts are displayed in great abundance. But here Tetrazzini is in a class of her own in the sheer magic she displays in that beloved note’s delivery – she seems, almost literally, to “pull them out of her hat” at will, just like a magician.

If one were to listen to one of Tetrazzini’s records and one only, it might be her enchanting rendition of Tosti’s little song Aprile. Here, the best of her talents and the flawed middle (which one critic likened to “the wailing of a cross infant”) are neatly summarized in about three minutes of music. She sings the simple melody with great charm and feeling and adds a breathtaking (not for her) high B flat at the end, almost as if to dispel any doubt that this is the great Tetrazzini at work.