No photo.

- Profession: Critic, musicologist, librettist, critic.

- Residences: Vienna, Prague.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 00-00-0000, Year

- Born: 14-12-1868 Prague, czech Republic.

- Died: 24-04-1922 Vienna, Austria.

- Buried:

“I want to see who can make a program for my Fifth!” (Gustav Mahler to Richard Batka in 1905).

Richard Batka studied at the University of Vienna German language with August Sauer and music history at Guido Adler and was built in 1893 for Dr. phil. PhD. 1896-98 he was together with Hermann Teibler in Prague, the “New Musical Review” out from 1897 he worked as an editor for the magazine “New Revue” and ” The Kunstwart “and for the” Prague day sheet “. In 1903 he founded the Austrian section of Dürer Federal Prague, which he also directed. 1906-07 he taught at the Prague Conservatory .

He moved to Vienna, where he was music critic of the 1908-1919 “Wiener Fremdenblatt”. Together with Richard Specht he was also editor of the magazine, founded in 1909, “The flag”. 1909-14 Batka taught at the Vienna Academy of Music music history . He wrote music history and music aesthetic writings and libretti and musical and literary texts translated from Czech, Polish, Italian and French into German. In 1960, in Vienna Währing (18th district) called the Batkagasse after him.

Prager Tagblatt September 20, 1908: An advocate for “modern” music, Richard Batka was seen as a central proponent of the work of Bruckner, Mahler, and Hugo Wolf, at the same time as having deepened the public’s understanding of Wagner’s music. From his student years onward, 1896 to 1898, Batka edited the Neue Musikalische Rundschau in Prague with Hermann Teibler. When it was absorbed into Ferdinand Avenius’s prestigious Munich arts journal Der Kunstwart, Batka continued as music editor. His first books dealt with German composers Schumann (1892), Bach (1892), Martin Plüddemann (1896)—and topics in early music (ancient Greece, 1900, and medieval polyphony, 1901).

Richard Batka (1868-1922), Bunte Buhne, 1902.

While still living in Prague, he published several collections of his reviews, which early on won an audience beyond Bohemia: Aus der Musik und Theaterwelt; Musikalische Streifzüge; Kranz: Gesammelte Aufsätze über Musik; Aus der Opernwelt: Prager Kritiker und Skizzen.” He was involved with various projects aimed at a broader public.

During these years, Batka was a central figure in Czech musical and intellectual life. At age thirty-two, he became a contributor on music to a volume on German cultural work in Bohemia.78 Batka subsequently published several books on music in Bohemia.79 He also wrote more libretti for Czech composers than for composers of any other nationality.80 His pride in Mahler’s Bohemian heritage is clear in the review translated below.

In 1908, after losing his job at the leading Prague newspaper Bohemia and writing for the Prager Tagblatt for several months without securing a position as music critic, Batka accepted an offer with the Wiener Fremdenblatt. Just at this time Mahler’s Seventh was premiered in Prague, and Batka published reviews in the Fremdenblatt and in revised form, in Der Kunstwart (as well as the review below). His most widely read book, a history of music, was published in three volumes (1909, 1911, and the third completed by Wilibald Nagel). Batka became well established in Vienna, editing Der Merker with Richard Specht from 1909 and teaching history at the Academy for Music and the Dramatic Arts. When the Fremdenblatt suspended publication in 1919 he was hired by the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung.

Opera was of special interest to Batka as a writer, but most of all as a librettist. He wrote a libretto for Lili Scheidl-Hutterstrasser (1882-1942?), perhaps the only woman to have had an opera produced at the Vienna Volksoper: Maria von Magdala (1919), published under her pseudonym Lio Hans. Batka wrote numerous libretti for Hungarian, Austrian, and German composers and also translated many libretti into German.

Gustav Mahler

Mahler came into contact with Batka when replying to his questionnaire about the nature of artistic creativity, an attempt to determine whether artists share cultural aspirations. The composer, for his part, lamented the amount of discourse and reflection on creativity and hoped instead that his works would elude any translation into language. Their exchange continued when Batka proposed writing a general article on Mahler and queried the composer on biographical matters as well as other issues, prompting the composer to a literary excursus on the nature of meaning in his music.

Batka remained an enthusiast for Mahler’s music, over and above his responsibility for covering performances in Prague (including a review of the Fifth Symphony for Bohemia). He was a correspondent for Die Musik (reviewing the First, Second, and Third Symphonies, and the Kindertotenlieder) and contributed several articles on Mahler to Der Kunstwart, including an obituary and a review of the Ninth Symphony.

A review reveals Batka as one of Mahler’s few contemporaries outside the anti-Semitic press to discuss Jewish identity. Two years later, spurred by Rudolf Louis’s anti-Semitic treatment of Mahler in his book on “contemporary German music,” he published an article on the “Jewish” qualities of Mahler’s music, opening with the same paragraph on Arthur Schnitzler as in the following review. The article appeared in Der Kunstwart, and may have influenced Moritz Goldstein, a young editor at the Goldene Klassiker Bibliothek who sparked an important debate over Jewish-German identity the following year in the very same journal.

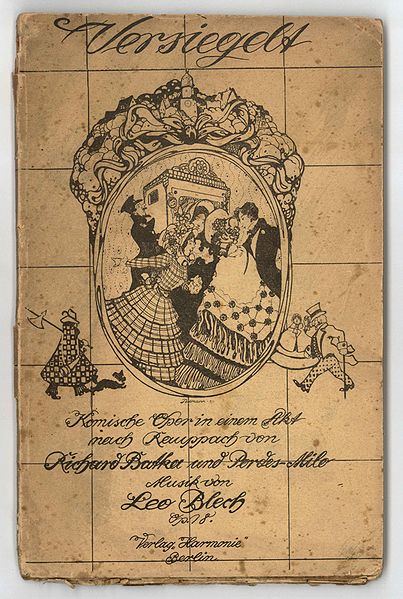

Libretto by Richard Batka (1868-1922).