- Profession: Violinist, composer.

- Residences: Copenhagen.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 09-06-1865 Sortelung (small village on the Danish island of Funen. It is located near Nørre Lyndelse and south of the city of Odense), Denmark.

- Died: 03-10-1931 Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Buried: Vestre Cemetery, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Carl August Nielsen was a Danish musician, conductor and violinist, widely recognized as his country’s greatest composer. Brought up by poor but musically talented parents on the island of Funen, he demonstrated his musical abilities at an early age. He initially played in a military band before attending the Royal Danish Academy of Music| in Copenhagen from 1884 until December 1886. He premiered his Op. 1, Suite for Strings, in 1888, at the age of 23. The following year, Nielsen began a 16-year stint as a second violinist in the prestigious Royal Danish Orchestra under the conductor Johan Svendsen, during which he played in Giuseppe Verdi’s Falstaff and Otello at their Danish premieres. In 1916, he took a post teaching at the Royal Academy and continued to work there until his death.

Although his symphonies, concertos and choral music are now internationally acclaimed, Nielsen’s career and personal life were marked by many difficulties, often reflected in his music. The works he composed between 1897 and 1904 are sometimes ascribed to his “psychological” period, resulting mainly from a turbulent marriage with the sculptor Anne Marie Brodersen. Nielsen is especially noted for his six symphonies, his Wind Quintet and his concertos for violin, flute and clarinet. In Denmark, his opera Maskarade and many of his songs have become an integral part of the national heritage. His early music was inspired by composers such as Brahms and Grieg, but he soon developed his own style, first experimenting with progressive tonality and later diverging even more radically from the standards of composition still common at the time. Nielsen’s sixth and final symphony, Sinfonia semplice, was written in 1924-1925. He died from a heart attack six years later, and is buried in Vestre Cemetery, Copenhagen.

Nielsen maintained the reputation of an outsider during his lifetime, both in his own country and internationally. It was only later that his works firmly entered the international repertoire, accelerating in popularity from the 1960s through Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) and others. In Denmark, Nielsen’s reputation was sealed in 2006 when three of his compositions were listed by the Ministry of Culture amongst the twelve greatest pieces of Danish music. For many years, he appeared on the Danish hundred-kroner banknote. The Carl Nielsen Museum in Odense documents his life and that of his wife. Between 1994 and 2009 the Royal Danish Library, sponsored by the Danish government, completed the Carl Nielsen Edition, freely available online, containing background information and sheet music for all Nielsen’s works, many of which had not been previously published. In 2015, the 150th anniversary of Nielsen’s birth, numerous celebratory performances of his works are scheduled.

Early years

Nielsen was born the seventh of twelve children to a poor peasant family at Nørre Lyndelse near Sortelung, south of Odense on the island of Funen. His father, Niels Jørgensen, was a house painter and traditional musician who, with his abilities as a fiddler and cornet player, was in strong demand for local celebrations. Nielsen described his childhood in his autobiography Min Fynske Barndom (My Childhood on Funen). His mother, whom he recalls singing folk songs during his childhood, came from a well-to-do family of sea captains while one of his half-uncles, Hans Andersen (1837-1881), was a talented musician.

Nielsen gave an account of his introduction to music: “I had heard music before, heard father play the violin and cornet, heard mother singing, and, when in bed with the measles, I had tried myself out on the little violin”. He had received the instrument from his mother when he was six.He learned the violin and piano as a child and wrote his earliest compositions at the age of eight or nine: a lullaby, now lost, and a polka which the composer mentioned in his autobiography. As his parents did not believe he had any future as a musician, they apprenticed him to a shopkeeper from a nearby village when he was fourteen; the shopkeeper went bankrupt by midsummer and Nielsen had to return home. After learning to play brass instruments, on 1 November 1879 he became a bugler and alto trombonist in the band of the army’s 16th Battalion at nearby Odense.

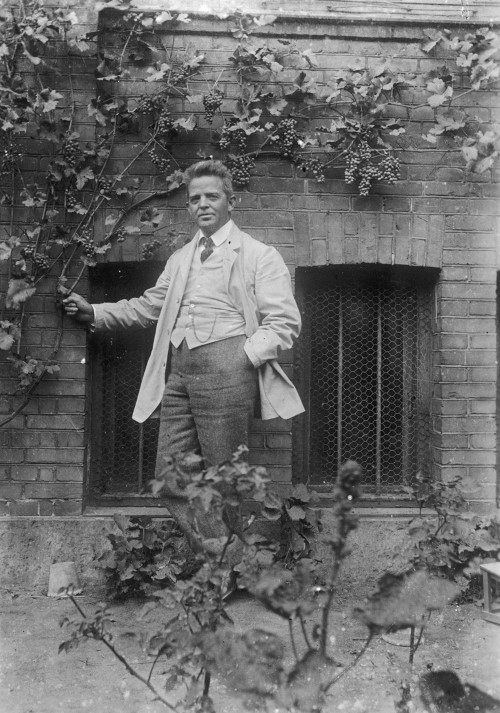

1879. Carl Nielsen in Odense

Nielsen did not give up the violin during his time with the battalion, continuing to play it when he went home to perform at dances with his father.The army paid him three kroner and 45 øre and a loaf of bread every five days for two and a half years, after which his salary was raised slightly, enabling him to buy the civilian clothes he needed to perform at barn dances.

Studies and early career

In 1881, Nielsen began to take his violin playing more seriously, studying privately under Carl Larsen, the sexton at Odense Cathedral. It is not known how much Nielsen composed during this period, but from his autobiography, it can be deduced that he wrote some trios and quartets for brass instruments, and that he had difficulty in coming to terms with the fact that brass instruments were tuned in different keys. Following an introduction to Niels W. Gade, the director of the Royal Academy in Copenhagen, by whom he was well received, Nielsen obtained his release from the military band at short notice, and studied at the Academy from the beginning of 1884.

Though not an outstanding student and composing little, Nielsen progressed well in violin under Valdemar Tofte (1832-1907), and received a solid grounding in music theory from Orla Rosenhoff (1844-1905), who would remain a valued adviser during his early years as a professional composer.He also studied composition under Gade, whom he liked as a friend but not for his music. Contacts with fellow students and cultured families in Copenhagen, some of whom would become lifelong friends, became equally important. The patchy education resulting from his country background left Nielsen insatiably curious about the arts, philosophy and aesthetics. But, in the opinion of the musicologist David Fanning, it also left him “with a highly personal, common man’s point of view on those subjects”. He left the Academy at the end of 1886, after graduating with good but not outstanding marks in all subjects. He then went to stay with the retired Odense merchant Jens Georg Nielsen (1820-1901) and his wife at their apartment on Slagelsegade as he was not yet in a position to pay his own way.While there, he fell in love with their 14-year-old daughter Emilie Demant.The affair was to last for the next three years.

On 17 September 1887, Nielsen played the violin in the Tivoli Concert Hall when his Andante tranquillo e Scherzo for strings was premiered. Shortly afterwards, on 25 January 1888, his String Quartet in F major was played at one of the private performances of the Privat Kammermusikforening (Private Chamber Music Society). While Nielsen considered the Quartet in F to be his official debut as a professional composer, a far greater impression was made by his Suite for Strings. Performed at Tivoli Gardens, Copenhagen on 8 September 1888, it was designated by Nielsen as his Op. 1.

By September 1889 Nielsen had progressed well enough on the violin to gain a position with the second violins in the prestigious Royal Danish Orchestra which played at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre, then conducted by Johan Svendsen. In this position he experienced Giuseppe Verdi’s Falstaff and Otello at their Danish premieres. Although this employment sometimes caused Nielsen considerable frustration, he continued to play there until 1905. After Svendsen’s retirement in 1906, Nielsen increasingly served as conductor (being officially appointed assistant conductor in 1910).Between graduation and attaining this position, he made a modest income from private violin lessons while enjoying the continuing support of his patrons, not only Jens Georg Nielsen but also Albert Sachs (born 1846) and Hans Demant (1827-1897) who both ran factories in Odense. After less than a year at the Royal Theatre, Nielsen won a scholarship of 1,800 kroner, giving him the means to spend several months travelling in Europe.

Marriage and children

While travelling, Nielsen discovered and then turned against Richard Wagner’s music dramas, heard many of Europe’s leading orchestras and soloists and sharpened his opinions on both music and the visual arts. Although he revered the music of Bach and Mozart, he remained ambivalent about much 19th-century music. In 1891 he met the composer and pianist Ferruccio Busoni in Leipzig; they were to maintain a correspondence for over thirty years.Shortly after arriving in Paris in early March 1891 Nielsen met the Danish sculptor Anne Marie Brodersen, who was also travelling on a scholarship. They toured Italy together and married in St Mark’s English Church, Florence, on 10 May 1891 before returning to Denmark. According to Fanning, their relationship was not only a “love match”, but also a “meeting of minds”; Anne Marie was a gifted artist and a “strong-willed and modern-minded woman, determined to forge her own career”. This determination would strain the Nielsens’ marriage, as Anne Marie would spend months away from home during the 1890s and 1900s, leaving Carl, who was susceptible to opportunities with other ladies, to raise their three young children in addition to composing and fulfilling his duties at the Royal Theatre.

Nielsen sublimated his anger and frustration over his marriage in a number of musical works, most notably between 1897 and 1904, a period which he sometimes called his “psychological” period.Fanning writes, “At this time his interest in the driving forces behind human personality crystallized in the opera Saul and David and the Second Symphony (The Four Temperaments) and the cantatas Hymnus amoris and Søvnen”. Carl suggested divorce in March 1905 and had considered moving to Germany for a fresh start, but despite several extended periods of separation the Nielsens remained married for the remainder of the composer’s life.

Carl Nielsen knitting to keep his heart rate down on a vacation in Jonsered, Sweden.

Nielsen had five children, two of them illegitimate. He had already fathered a son, Carl August Nielsen, in January 1888, before he met Anne Marie. In 1912, an illegitimate daughter was born – Rachel Siegmann, about whom Anne Marie never learned. With his wife Nielsen had two daughters and a son. Irmelin, the elder daughter, studied music theory with her father and in December 1919 married Eggert Møller (1893-1978), a medical doctor who became a professor at the University of Copenhagen and director of the polyclinic at the National Hospital. The younger daughter Anne Marie, who graduated from the Copenhagen Academy of Arts, married the Hungarian violinist Emil Telmányi (1892-1988) in 1918; he contributed to the promotion of Nielsen’s music, both as a violinist and a conductor. Nielsen’s son, Hans Børge, was handicapped as a result of meningitis and spent most of his life away from the family. He died near Kolding in 1956.

Mature composer

At first, Nielsen’s works did not gain sufficient recognition for him to be able to support himself. During the concert which saw the premiere of his First Symphony on 14 March 1894 conducted by Svendsen, Nielsen played in the second violin section. The symphony was a great success when played in Berlin in 1896, contributing significantly to his reputation. He was increasingly in demand to write incidental music for the theatre as well as cantatas for special occasions, both of which provided a welcome source of additional income. Fanning comments on the relationship which developed between his programmatic and symphonic works: “Sometimes he would find stageworthy ideas in his supposedly pure orchestral music; sometimes a text or scenario forced him to invent vivid musical imagery which he could later turn to more abstract use.”

Nielsen’s cantata Hymnus amoris for soloists, chorus and orchestra was first performed at Copenhagen’s Musikforeningen (The Music Society) on 27 April 1897. It was inspired by Titian’s painting Miracle of the Jealous Husband which Nielsen had seen on his honeymoon in Italy in 1891. On one of the copies, he wrote: “To my own Marie! These tones in praise of love are nothing compared to the real thing.”

Beginning in 1901, Nielsen received a modest state pension (initially 800 kroner per annum, growing to 7,500 kroner by 1927) to augment his violinist’s salary. This allowed him to stop taking private pupils and left him more time to compose. From 1903, he also had an annual retainer from his principal publisher, Wilhelm Hansen Edition (da). Between 1905 and 1914 he served as second conductor at the Royal Theatre. For his son-in-law, Emil Telmányi, Nielsen wrote his Violin Concerto, Op. 33 (1911). From 1914 to 1926, he conducted the Musikforeningen orchestra. In 1916, he took a post teaching at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in Copenhagen, and continued to work there until his death.

The strain of dual careers and constant separation from his wife led to an extended breach in his marriage. The couple began separation proceedings in 1916, and separation by mutual consent was granted in 1919. In the period 1916-1922, Nielsen often lived on Funen retreating to the Damgaard and Fuglsang estates, or worked as a conductor in Gothenburg. The period was one of creative crisis for Nielsen which, coinciding with World War I, would strongly influence his Fourth (1914-1916) and Fifth symphonies (1921-1922), arguably his greatest works according to Fanning. The composer was particularly upset in the 1920s when his long-standing Danish publisher Wilhelm Hansen was unable to undertake publication of many of his major works, including Aladdin and Pan and Syrinx.

The sixth and final symphony, Sinfonia semplice, was written in 1924-1925. After suffering a serious heart attack in 1925, Nielsen was forced to curtail much of his activity, although he continued to compose until his death. His sixtieth birthday in 1925 brought many congratulations, a decoration from the Swedish government, and a gala concert and reception in Copenhagen. The composer, however, was in a dour mood; in an article in Politiken on 9 November 1925 he wrote:

If I could live my life again, I would chase any thoughts of Art out of my head and be apprenticed to a merchant or pursue some other useful trade the results of which could be visible in the end … What use is it to me that the whole world acknowledges me, but hurries away and leaves me alone with my wares until everything breaks down and I discover to my disgrace that I have lived as a foolish dreamer and believed that the more I worked and exerted myself in my art, the better position I would achieve. No, it is no enviable fate to be an artist.

Final years and death

Nielsen’s final large-scale orchestral works were his Flute Concerto (1926) and the Clarinet Concerto (1928), of which Robert Layton writes: “If ever there was music from another planet, this is surely it. Its sonorities are sparse and monochrome, its air rarefied and bracing.” Nielsen’s last musical composition, the organ work Commotio, was premiered posthumously in 1931.

During his final years, Nielsen produced a short book of essays entitled Living Music (1925), followed in 1927 by his memoir Min Fynske Barndom. In 1926 he wrote in his diary “My home soil pulls me more and more like a long sucking kiss. Does it mean that I shall finally return and rest in the earth of Funen? Then it must be in the place where I was born: Sortelung, Frydenlands parish”.

This was not to be. Nielsen was admitted to Copenhagen’s National Hospital (Rigshospitalet) on 1 October 1931 following a series of heart attacks. He died there at ten minutes past midnight on 3 October, surrounded by his family. His last words to them were “You are standing here as if you were waiting for something”. He was buried in Copenhagen’s Vestre Cemetery; all the music at his funeral, including the hymns, was the work of the composer.After his death his wife was commissioned to sculpt a monument to him, to be erected in central Copenhagen. She wrote: “I wanted to take the winged horse, eternal symbol of poetry, and place a musician on its back. He was to sit there between the rushing wings blowing a reed pipe out over Copenhagen.” Dispute about her design and a shortfall in funding meant that erection of the monument was delayed and that Anne Marie herself ended up subsidising it. It was finally unveiled in 1939.