- Profession: Conductor, composer, director conservatory Dusseldorf.

- Residences: Dusseldorf, Cologne, Berlin, Paris.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 00-00-0000, Year

- Born: 07-05-1851 Wiesbaden, Germany.

- Died: 12-03-1920 Dusseldorf, Germany. Aged 68.

- Buried: Unknown.

Julius Buths was a German pianist, conductor and minor composer. He was particularly notable in his early championing of the works of Edward Elgar in Germany. He conducted the continental European premieres of both the Enigma Variations and The Dream of Gerontius. He also had notable associations with Frederick Delius and Gustav Mahler.

Julius Emil Martin Buths was born in Wiesbaden, the son of an oboist. He studied music at Cologne under Ferdinand Hiller and others, in Berlin under Friedrich Kiel, in Italy and in Paris. He worked as a conductor in Breslau from 1875 to 1879, then in Elberfeld until 1890. That year he was appointed musical director for the city of Düsseldorf, and he played an important role in the Lower Rhenish Music Festivals for a number of years. In 1890, he was co-director with Hans Richter; in 1893 he was sole director; in 1896, he shared the role with Johannes Brahms and Richard Strauss; 1902 co-director with Strauss; and sole director in 1905. In Düsseldorf he frequently played chamber music with Max Reger and Joseph Joachim.

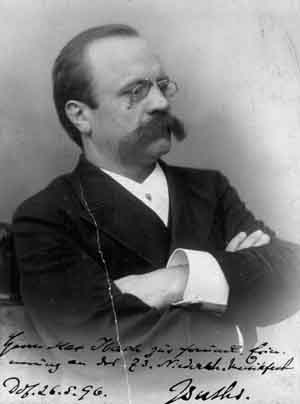

Julius Buths (1851-1920) in 1902.

He conducted Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in Düsseldorf on 03-04-1903, in preparation for which he engaged in correspondence with the composer, who advised him to ensure a significant pause between the first and second movements. Buths nevertheless inserted the long pause (five minutes) between the fourth and fifth movements, for which Mahler congratulated him on his insight and sensitivity, and courage in daring to ignore the composer’s wishes.

In March 1903, when Julius Buths conducted the Symphony in Düsseldorf with a pause between the Urlicht and the finale, Mahler wrote to him, congratulating him on his insight:

Thus the main break in the concert hall will be between the fourth and fifth movements. I am amazed by the sensitivity of feeling that enabled you to find the natural division of the work, and this contrary to my own indications. I have long been of the same opinion, and all the performances I have conducted have only strengthened it. Nevertheless, a pause must also be made after the first movement, because otherwise the second will seem a mere discrepancy. . . . The Andante is a kind of intermezzo (like a last echo of bygone days in the life of the man who was carried to his grave in the first movement—”for the sun still shines upon him”). Whereas the first, third, fourth and fifth movements are connected as to theme and atmosphere, the second stands alone and rather interrupts the austere progression of events. Perhaps this is a weakness in the plan, but my intention is certainly clear to you now . . .

A review in the New-York Daily Tribune on December 9, 1908, reported that Mahler did take two five-minute pauses when he conducted the Second Symphony in that city, but he made no alteration to the score in this respect. His confidante Natalie Bauer-Lechner recalled that when he introduced the work in Vienna, in 1899, “he actually repeated the Urlicht because the audience had applauded when it concluded, and Mahler said that the fifth movement had to be played attaca.” That was apparently his final decision as well. In any event, the years between the composition of the Symphony and that letter to Buths found him explaining or justifying the work’s programmatic content several times. About a week after the full premiere, in December 1895, he wrote to the critic Max Marschalk:

The original aim of this work was never to describe an event in detail; rather it concerns a feeling. Its spiritual message is clearly expressed in the words of the final chorus. . . . The parallel between life and music is perhaps deeper and more extensive than can be drawn at present. Yet I ask no one to follow me along this track, and I leave the interpretation of details to the imagination of each individual listener.

In 1906, along with Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Alban Berg and Oskar Fried, he attended the rehearsals for the premiere of Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 in Essen and they all dined with the composer.

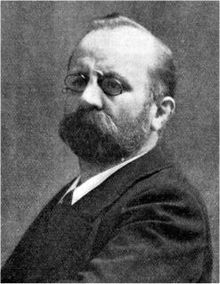

Left to right, Fritz Cassirer (conductor) with Julius Buths (1851-1920), Frederick Delius (composer), Hans Haym (conductor) and Jelka Delius (Fredericks’ wife) in 1905.