Transcript

In the second movement Mahler once again indulges his penchant for parody for the use of popular dance music as a parable to the societal decadence of his time. He does not just offer dances such as the Waltz, Ländler and minuet as light entertainment, but opposes them in combat, thereby mirroring the battle of the first movement on a more mundane level, conceptual parallels between the first two movements about even a few purely musical relationships exist between them. In essence, the altercation between the abstract life affirming and life negating forces in the opening movement gives way to the proverbial battle between the earthy, more nature oriented spirit of country life symbolized by the Ländler, and the stylized sophistication of city life, represented by the Waltz. Although Mahler loved Vienna, he was never comfortable in social world, his predilection for natural surroundings may well have been more conceptual and real. Nevertheless, Mahler treats the dances that constitute the principal subjects of the second movement as representative symbols for the antagonism of nature vs. civilization, treating the conflict between them with humor wit, and sometimes biting sarcasm.

The first comment could be described as the naive rambunctious peasant, represented by the bumptious Ländler, whose antagonist is the rude, arrogant sophisticate, represented by a stylized Waltz. To this pair of opposites, Mahler adds a third subject, a warm, tender minuet not as a middle ground, but to enhance the contrast between the two antagonists. He refers to the minuet as another Ländler, in order to separate it as much as possible from the hard-driven Waltz, as the movement progresses, the lender seems to go astray. It tries to join the Waltz’s gay romp, awkwardly stumbling in where it is clearly not wanted. distorted waltz music abounds with grotesque curries and vulgar clowning on cheap popular tunes, dissonant key switches disrupt smooth harmonic progression. In the midst of these vulgarisms, if you will, the nostalgic minuet provides momentary relief, much in the way that the subsidiary freúen die leben theme did in the first movement. Bruno Walter suggests that the destructive effect of the antagonism between Waltz and Ländler signifies that for Mahler as for Europe, the dance is over, old Europe was anthropomorphized into an aged representative of tradition, suffering from decades in the throes of its own demise. In the process of this conflict of opposites, as Deryck Cooke so succinctly puts it, “Waltz rapes Ländler”. If Mahler intended us to take this ray pine victory of waltz over ländler as a musical representation of the European social milieu of his time, in which the cosmopolitan vanquishes the rustic, it would appear that he does not celebrate the victory. At the end of his life, Mahler seemed to have been caught up in recollections of his youth, in an idealized memory of country life, so very different from the Viennese society that he never quite fit into, and that ultimately rejected him. Consequently, his sympathies are clearly with the landler that clownishly stumbled through the movement. In contrast, the waltz is confident, increasingly aggressive, and sometimes brash. One might consider these two subjects as worldly manifestations of the life-affirming and life-denying antagonists engaged in mortal combat in the first movement, the ländler, affirming the natural innocence of life, the waltz, its sophisticated rival, seeking to trample naturalism underfoot. Surely the angst of the first movement’s engagement does not infect this conflict, victory is not achieved by a devastating blow, and no dark visions cloud the gay light-hearted atmosphere, but one can see through the surface, that everyday life is often frivolous, tawdry and empty. Other relationships between the first two movements are worth noting, both function through contrasting themes that become so confused with each other that they almost lose their distinctiveness. Both movements end with their respective first subjects fading out, disintegrating into oblivion, if you will, in harmonic terms, the fall of a whole step from D major, the first movement to C major in the second movement, both implies the mode of a farewell and symbolizes the descent from abstraction to reality. Adorno refers to the movement as a “totem dance”, the dance of death, he models direction at the violence play like fiddles Adorno, sees a connection between this movement and the scherzo of the fourth simply in its treatment of dance music, the second movement also relates most directly to the middle movement of the fifth.

There is a distinctive conceptual relationship between the first and second movements of the ninth and the opening movement and scherzo of the Sixth Symphony. In the six the hero of the first movement is mockingly character toured in the scherzo of the ninth. The second movement does not react to the first in this way but transfers the conceptual dualism between life-affirming and life-negating forces in the first movement onto a worldly plane of contrasting social characteristics. Mahler presents these contrasting subjects in a musical montage that Adorno suggests anticipates Stravinsky, in both their quotation-like themes and their decomposition and lopsided reunification. Mahler parades before the listener musical cliches played with tongue-in-cheek drollery that cook considers to have been, as he put it, “divested of all charm, life, and significance”.

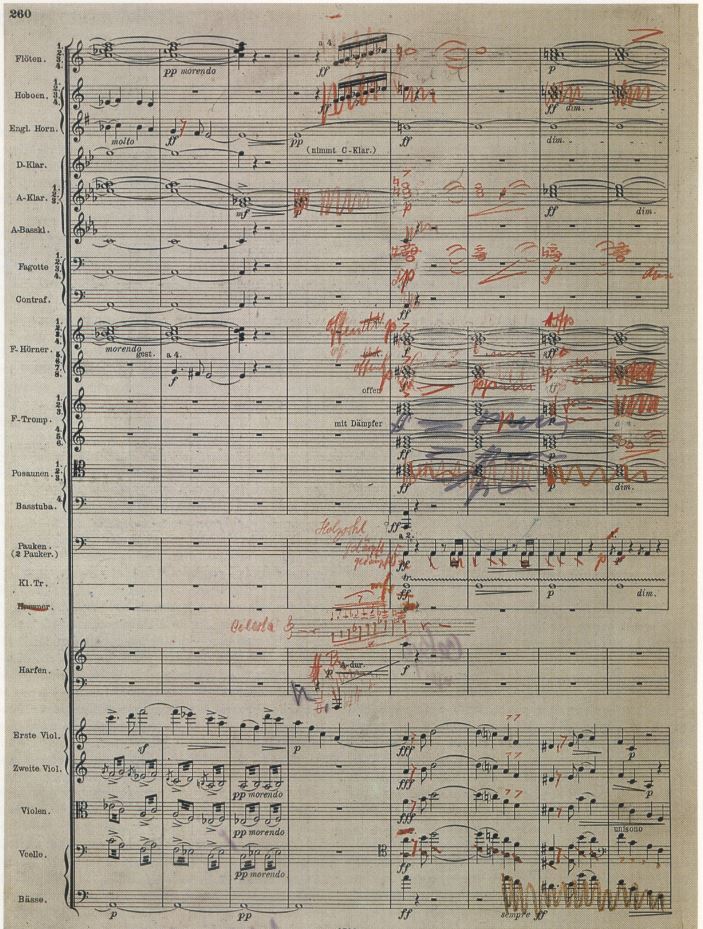

The second movement begins with an introductory dialogue between two unusual instrumental combinations, bassoons and violas on the one hand, and three clarinets and a bass clarinet on the other. The former group offers a light flip and figure consisting of a rising upbeat, a four staccato 16th, followed by two repeated notes on even beats, we’ll call that motive A, and here it is.

The latter instrumental group plays a congenial version of the motive of farewell on three square beats, emphasizing the first beat and decorating it with grace notes, we’ll call that motive B.

This three-node pattern is taken down a full step, thus creating a new motivic variant.

These two six-beat phrases serve as motivic references to the ländler subject, which they introduce, motive A continues repeating its merry little figure until the lender theme enters rather brusquely in the second violins. It has a completely different character from the introductory motives and sounds like a crude, boisterous and heavy-footed peasant dance. The themes contour is also interesting, it begins on a rising three-note upbeat, a curious allusion to the motive of longing that leads to a trilled quarter note in compensating a fourth and then the phrase proceeds in the opposite direction, ending with a trilled quarter note, in reverse of the pattern of motive A.

Mahler directs the violins to play like fiddles with strong emphasis on down beats to add rusticity to this peasant dance theme. Despite reinforcing first beats Mahler accents the second beats of the theme, horns add and Harrigan three note figure sounding like a little horn call. It begins with a rising fourth, that falls by a second motor of a farewell to a trill half now. The entire process is repeated in abbreviated form with fuller instrumentation, as the landler theme undergoes a brief development, while motives A and B form part of the musical fabric. The music is game playful, seeming to express genuine naivete.

As the ländler continues horns enter raucously with an accompaniment of seemingly repeated grace noted chords that embellish the peasant-like character of the main theme.

More sluggish than other lenders, this one seems to exaggerate its country bumpkin character to a fault. Despite contrapuntal treatment, each thematic and motivic element comes through clearly and distinctly. Individual voices seem to fall over each other clumsily, a cheerful version of motive D and violins recalls the opening movements’ first theme.

As often happens with Mahler’s dance music, the first subject concludes as its main theme begins to break apart, it softens and recedes into the bass. horns played motive B at the close, overlapping with a variant of the 16th note upbeat of motive A, that functions as the upbeat to the second theme, which immediately follows, in a new slightly faster tempo, the second subject begins with a waltz in E major. It begins with motive B of the ländler, accenting and reconfiguring the third beat. The theme also contains a four-node rising scale that relates ironically to the ländler theme. Both themes contain the mode of a farewell the following major second, does despite their differences in temperament and style, the countrified ländler and citified waltz have several common elements. The second part of the waltz theme has a caricaturesque quality, apparent in its flighty figuration, this too is sourced in the first subject.

A direct quote from the fish pretty movement of the second symphony is played by a pair of horns, hinting at the confused rowdy state of things in the senseless hustle-bustle of modern life.

As the waltz theme develops, motive B contained within it makes wider into valic plunges, grace notes and strong accents on the first note of motive B given more thrust, but also connected with the ländler. Sometimes the rhythm seems to get confused, awkwardly stumbling over itself in a manner that would be more likely to occur in the ländler, the prominence of the farewell motive the falling major second in the waltz theme, implies sympathy for the passing of Vienna’s Golden Age. As the intervallic plunges of motive B become increasingly wider and more pronounced, trombones and tuba enter with the new waltz theme in E flat major, a convoluted variation of the first waltz that mangles motive A and B. The tawdry even vulgar character this theme is conveyed in a humorous spirit, it to pokes fun at the mindless whirl of Viennese society, in its buffoonery, it might be likened to Stravinsky’s outrageous circus polka, especially in its use of trombone and tuba for the dance theme with oompah rhythms as accompaniment. Violins and flutes insert a descending chromatic phrase in dactylic rhythm that stresses and elongates the first beat, it will become increasingly significant as the movement proceeds.

Just when this absurd waltz tune seems to settle in, motive A of the ländler suddenly enters assertively in the horns in walls temporal, clearly out of context, motive B follows due to flee as they try to return to the dialogue from waltz back to ländler. In a short while, the waltz has had about enough of this unwelcomed intrusion with a discourteous wave of the hand, it brusquely thrusts the ländler aside, having succeeded in getting rid of this annoyance, the waltz continues more voicetress and obnoxious than ever. Its silly scraps of figuration are dashed off mindlessly throughout the orchestra over a variant of motive B and winds, with the horns little arrogant figure now distorted by bass strings.

At last, the waltz figuration begins to fragment if reluctantly, and the tempo slows down, signaling the end of the second subject, the repeated three-note upbeat in the bassoon seems to hint at the return of the ländler theme, but instead, the third subject makes its first appearance, following along retard, at a slower and more relaxed pace, a new ländler theme appears firmly set an F major. It begins by repeating the motive of a farewell four times. The first two times in iambic rhythm, the second two in dotted rhythm. It is accompanied by a rhythmic phrase that combines a trilled note that falls by a fourth with a three-note upbeat of a ländler theme, and also doubles the first note of farewell with which the third theme begins. Although Mahler designates this new theme as a ländler, it is more in the nature of a slow minuet more tender and sentimental than both proceeding dance subjects. An inverted version of the three-note upbeat serves as a repeating rhythmic undercurrent. Some of the themes characteristics recall the cloggin oboe theme from the scherzo the Seventh Symphony.

After the tempo slows down substantially for a moment, the original tempo set for the first ländler theme is reinstated for the continuation of the third theme in a bright A major with this adjustment to a slightly faster pace. The otherwise warm and sentimental third theme takes on the more droll characteristics of the first blend blur Mahler toys with a rhythmically square third theme, reconfiguring its upbeat in a variety of ways, giving it a lyrical and then flighty character by turns. Each revision is made to sound more playful by occasional light strokes and trills on the triangle, clarinets mimic the grace noted repeating tones played by the horns earlier to lift the ländler spirits. After a brief digression to B flat minor, and a short retard, the minuet theme starts over again in F major. This time the tempo becomes livelier, only to slow up again, as inner strings and woodwinds anticipate the return of the waltz theme, with fragments of its silly figuration.

Still played in the slow tempo of the retard the upbeat of the waltz theme sourced in motive a and earlier in the scherzo in finale of The sixth Symphony, archers in its reprise in D major, much in the same manner as the upbeat of motive a entered during the waltz music in an attempt to bring back the first ländler. This time Mahler sets the tempo at a slightly faster clip, making it sound more hasty and agitated, he inserts turn figures into the waltz theme, thus anticipating their use in the finale. Here they sound tasteless and shallow, a far cry from the hymnal quality they will take on in the last movement. It is as if Mahler marks the deeply felt music of the finale, even before it appears, something he will do even more demonstratively in the next movement. Occasional strokes of the glockenspiel make the flipping figuration of the walls sound even more frivolous. Mahler frequently scatters these motivic elements around the worker strip or combines particular motives in a manner that will greatly influence the next generation of Viennese composers, particularly sure in Berg and Wabern.

Soon the waltz becomes so wrapped up in itself, that it loses control of the tempo, which becomes increasingly faster. Finally, Mahler pulls back the reins, as if gradually reining in a wild horse, repeating double noted eighth to the violins bring back tempo three, and the gentler strains of the third theme.

Our next excerpt begins with the return of the waltz subject in D major.

The third theme undergoes further development, principally by inverting the farewell motive and stretching the themes intervals, for a few bars, the inane figuration of the waltz threatens to bring it back but the third theme withstands the waltz meager and short-lived attempt to intercede having succeeded in staving off the waltz return, the third theme gains momentum. But this too is short-lived, for it catches itself in the act of becoming overly aggressive, or simply exhausts his energies, and gently seems to fall asleep with a long yawn a farewell the last note of which is sustained and fades away into a restful slumber.

When the last sounds of farewell become so faint as to be hardly audible income two bassoons sheepishly playing their cute little motive A, other woodwinds, dude if we follow by demonstrably asserting motive B as at the beginning of the movement.

And so the first subject returns in its home key of C, but the orchestration has pared down, and the ländler seems substantially weaker. A Piccolo hints at this by playing only its three-note upbeat, and a fragment of the waltz figuration. When the ländler theme itself appears it is but a mere shadow of its former self, its exuberance all but having disappeared as it enters first in a solo viola and cellos and later in a solo violin. Motives A and B become more assertive as the first subject continues. But the waltzes figuration creeps in, threatening to take over, brass and woodwinds try to prevent this interference with strong pronouncements of motive B would sound ominous in C minor. The waltz figuration struggles to take hold on the horse reigning rhythms that previously led to the reprise of the third subject, apparently out of place here, it is the waltz that takes over instead. This time it offers a new thematic twist with a more strident and bullish walls than its sister theme gets still related to it. Long plunges on the first beat of the square wolves rhythm that had been forcefully riveted into the wolves theme here become even more exaggerated. A falling chromatic phrase in horns sounds uncharacteristically dove.

As the tonality rises a minor third to G flat, woodwinds in octaves way allowed a new counter theme, its lyrical character distorted by shrieking dissonant chords and woodwinds, trumpets already hinted at this strangely contorted tune during the reprise of the second subject. Violence restated after the waltz continues to become rougher and more aggressive.

An even more boisterous version of the waltz theme for the full orchestra is set in complex CounterPoint. As the tempo increases, the orchestra shrinks to an ensemble of woodwinds strings and glockenspiel, which play a new variant of the waltz theme, this variant begins with motive B, and includes an outline of the shrieking woodwind counter theme. The tempo gradually increases as the waltz becomes deliriously wild, it’s silly figuration seeming to approach madness. A trumpet tries to hold it back with the farewell motive, as if to remind the waltz that has vaulted suggested the dance is over but violins merely mock the trumpet with inane repetitions of farewell. The rest of the brass come to its aid with a variant of the farewell motive that adds the little arrogant motive, first stated by two horns during the introduction, horns will fully engage with the 16th note upbeat of motive A still in waltz tempo, but they catch themselves immediately, and the original tempo one of the ländler is suddenly and unexpectedly resumed.

All elements of the first subject returned now scattered about in woodwinds and strings falling over each other clumsily. The sense of dysfunction and disorder becomes increasingly apparent. Even the tonality sours from major to minor for a time. Bitterly dissonant chord blasts out in winds are ushering in the closing section, flutes and oboes descend with a series of minor seconds the motive of whoa played earlier by now set against chromatically ascending quarter notes and clarinets and other horns, a rising series of eighth’s in first violins moving upward by consecutive three-note sequences of a rising fourth, followed by a falling minor second, seem to plead for peace. This ascending violin phrase will return in the finale, but the violins ascent ends on a diminished fifth, the notorious musicas in diablous of the Middle Ages that bodes ill for the unfortunate ländler. A bridge passage to the closing section begins as cellos and then bases enter strongly on bouncing repeated eighth notes, while different groupings of woodwinds grotesquely how old a scrap of the waltz is silly figuration, shifting between major and minor with each repetition.

Mercilessly the waltz marks the poor little endler horns conclude the preliminaries to the final measures, with a sad version of motive B forcing the tonality into the minor. The intrusion of marching drum beats on falling fourths on the timpani seem out of place in this dance movement. Yet, they might hint at the waltz his own victory march.

Now the orchestra shrinks to a chamber ensemble, for the most part brass are devoted to playing only supporting chords, except for a solo horn that calls out a falling sequence of long tone farewells, and a horn trio that plays a scrap of grace note and repeating tones that once accompany the chipper ländler to music that was happy and full of life now seems to be enveloped in shadow and gloom, woodwinds play a hollow sounding fragments of the waltz, as they participate in the general disintegration of the dance with scraps of the waltz is figuration.

A solo violin and viola sound like the diabolic throwing hind, whose image is often referred to in connection with the scherzo one of the Fourth Symphony, various elements of both waltz and ländler, are dashed off willy nilly in different sections of the reduced orchestra. Gradually, the temple whines down until only motives A and B, and the barest scraps of the ländler can be heard from the few instruments that remain. The tonality is suspended on the dominant for several measures, as if the music tries to hold on for dear life to what is left of its former self, until the long sought after major mode finally returns.

Piccolo and contrabassoon combined to put the movement out of its misery with motive A moving to the tonic rather gracefully, the ones happy go lucky ländler virtually dissolves, it ends with one last bit of playful frivolity, has a fitting conclusion to the music reminiscent of the era when waltz and ländler were king.

Notice that the third subject remains relatively unscathed after the conflict concludes, but it’s more somber evocations of farewell permeate the closing section. It is as if we have just witnessed an homage to the joys of youth seen through the eyes of old age, in the senseless conflict between the cosmopolitan and countrified, sophisticated and earthy, these opponents take on characteristics of each other, with the poor peasant getting the worst of it, and finally falling to pieces at the end. But in the process, the cosmopolitan shows that he can be just as coarse, witless and gruff as his country neighbor, also much more antagonistic and unfriendly. The simple little ländler may sense this when it ends the movement with a Koi little wink of motive A.

By Lew Smoley