Transcript

In the third movement, as in so many of Mahler’s scherzo’s, his inner demon takes center stage, it has been aptly referred to as Mahler’s dance macabre. Unlike the principal subjects of the scherzo of the sixth and seventh symphonies, however, the ninth scherzo is neither mocking nor parodic. Instead, it reveals the ferocious and violent side of the demonic spirit. Only the second movement of the fifth is comparable in raging fury and savage brutality. It would seem that the life-negating forces of the first movement strengthened by their victory, seek to only destroy what they have defeated. Yet the rondo burlesque, as the title implies, is not devoid of width and mimicry. For example, a subsidiary theme is coyly playful, a trivial little tune that could well be intended as a parody of innocence or naivety as in the Sixth Symphony scherzo. Similarly, this subsidiary theme, with its light dance step rhythm relates to the lander of the proceeding movement, but the demonic first subject never becomes embattled with this carefree subsidiary theme. They appear side by side without engaging one another. This lack of direct confrontation may be due to their common source, the spirit of nihilism, the first of the active sword, the second passive.

A few moments of relief occurred during the calmer middle section when the fierce onslaught of the first subject disappears in a ray of light that shines through the lurid darkness. Not only does the movement’s central sections sue the beleaguered spirit of the opening section, but it evokes fond memories of a more peaceful time when the spirit was not subjected to savage attacks of its inner demons. Such recollections fit well within the context of a symphony that expresses Mahler’s farewell to life. The prevalence of D major during the central interlude recalls the warm, comforting atmosphere of the opening movements first subject, incidentally in the same key, with orchestral forces substantially reduced the polyphonic complexity of the scherzo subject deflates into sustain chords that embellish the sequential thematic design. The dreamy trumpet theme from this section contains a Wagnerian turn that is prophetic of the finale’s principal theme after a sequence of variations on this theme, the demon reappears in the guise of an E flat clarinets flippin phrased that nastily marks the turn theme, by distorting its tender smile into a satanic horrible grimace. The appearance of this wicked figure is a signal for the demonic first subject to make its way back stealthily to center stage. Thereafter, the para gistic second subject is heard no more. All that remains is the raging fury of the first subject, which becomes increasingly rabid until it ends with the same violent rhythmic figure with which it began. A virtuoso piece par excellence, the rondo burlesque requires consummate skill from every member of the orchestra, the conductor must make an extraordinary effort to maintain control and balance the various elements presented in complex polyphony to achieve a clear and comprehensive performance in terms of tonality, affirm harmonic basis is infrequently achieved in the face of frequent key displacement. Complex use of dissonant linear counterpoint produces a chaotic confluence of dramatic and motivic material.

Deryck Cooke refers to rapid vehement motives with rhythmically disjointed counterpoints that create the effect of disordered pandemonium. Yet, the movement is highly structured and intricately designed, unlike thick textured passages in for example, a Strauss tone poem in which countervailing lines merely serve to produce an overall sonic effect in a confluence of component parts, in the ninth scherzo each thematic or motivic figure in multi dimensional counterpoint serves its own purpose, and consequently must be heard. As in so many of Mahler’s middle periods scherzo elements of the principal thematic material are presented at the very beginning of the movement as musical cells, which are assembled to form the main theme and then disassembled for use as motives that appear either in isolation or as part of dense counter point. As Donald Mitchell suggests, Bahian polyphony is a major influence here, as it was in the middle period symphonies, but Mitchell adds the use of polyphonic techniques that only pay homage to the past, but look forward to the modern era, as for example, he refers to (quote), “the way in which Mahler twice in the reprise of the movement tries to dam up with an interrupted cadence, that turbulent onward flow of the music, and twice the flow thrusts on unimpeded, until it reaches its final climactic base”.

Mahler used a similar technique in the finale of the Seventh Symphony, by collapsing and approaching cadence of the march subject into the minuet, before the march reaches closure. In this scherzo, Mahler both looks back to the previous movements, a destructive force of the first movement, second subject, and the forceful wall subject of the second movement and forward to the finale, with the appearance of an important thematic phrase that will be transfigured in the last movement. Those the scherzo functions as a pivotal movement relating to the conflict presented in the earlier movements, as well as foreshadowing the Arden prayer for redemption so moving we expressed in the finale, three principles cellular motives are stated sequentially at the beginning of a movement, they will can join to form the first theme. They may be characterized as arrogant, obstinate and short tempered.

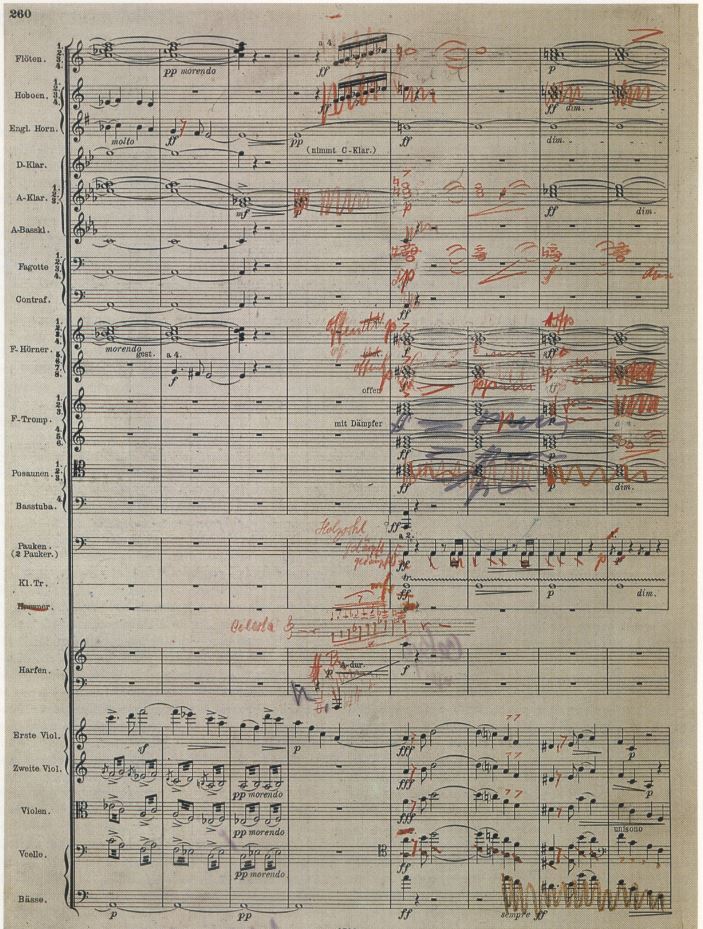

– The first motive, motive one, stayed into the very beginning of the movement by the solo trumpet consists of three notes comprised of a rising second, followed by a falling diminished fifth, the use of this interval, the notorious musicas in diabolus has already hints at the devilish character of the movement. This three node figure recalls certain elements from the previous movements. It’s anapestic rhythm frequently appears in the first movie, and its basic shape recalls its appearance of the development of the second movements waltz theme. The source of motive one, however, is the trumpet call that bursts forth from the cataclysmic eruption that begins the finale of the Second Symphony, the motive of terror.

By way of the horn call that begins the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony, motive one is immediately followed by an upward arching five note figure coarsely asserted by the strings. We’ll call this motive two

– Motive two is a mirror image of the eighth note variant of motive be from the first movement, with a quarter note added at the end, it also harkens back to the violence second movement of the Fifth Symphony, where it appears at the very beginning in the strings.

– After the horns repeat motive, one woodwinds and low strings play another motive, motive three. This consists of three chords that rise stepwise, and are played firmly and forcefully in a short, long, long rhythmic scheme. Motive three gives the impression that it only begins what might have become a heroic theme, if it was not cut short before it has a chance to fully develop. In this respect, it resembles the opening notes of the principal theme from the finale of the First Symphony. These three motives are combined into the principal theme of the movements opening section, the scherzo section. They are treated both in combination and independently throughout the opening section, and it’s later reprises. Let’s listen to the opening of the movement. Notice how many twists and turns the three motives undergo after they are presented at the beginning.

Combination of biting intensity and devilish jocularity imbue the music with a character akin to that of Strauss’s Till Eulen Spiegel, but with little of its drawl humor and impish rascality during the scherzo section, the principal theme has developed in multifarious permutations and combinations of its motivic elements, which are playfully reconfigured at each turn, and scattered throughout the orchestra in an endless variety of instrumental arrangements. As in the second movement, pure figuration is used as part of the thematic development chamber, like in instrumental groupings contrast with enormous orchestral tooties, frequently shifting emphasis between winds and strings. Sometimes the music sounds forceful and strident, as in the initial appearance of the first theme, elsewhere it becomes impishly playful, as when strings and a few wins quietly throw scraps of the motives back and forth.

As the first subject grasses, motivic intervals widen and triplet rhythms permeate both themes, and they’re accompanied by a new three-node falling figure, which is an inverted variant of motive three recalls the B major variation of the march theme of the sixth symphonies first move. Increasingly, the music takes on the character of a lively march. Even the Pan march theme from the third symphonies first movement makes an appearance. Fashion hear from elements of the first theme.

Full of swagger and bravado, the first subject continues to develop until trombones and tuba strongly assert heroic tattoos in the same rhythm with which the solo trumpet opened the Fifth Symphony. They seem to bring the orchestra together for a new variation of the first theme that continues in the strings with full force, and then in various wind groupings, played in stretto. Repeated descending phrases in the bass give this theme heft as well as an unnerving power. Another variation of the main theme in D minor, played by trombones and tuba on stretched intervals of motive three combines with motives one and two, all sounding ominous against swirling figuration. Grace noted offbeat rhythms and trills on the first note of a variant of motive one, enhance the theme’s demonic character while skipping rhythms give it a jocular quality. There can be no mistaking the first subject’s combination of devilish mockery, willful arrogance, and intense rage.

Toward the close of the first section, when only the strings continue with the main theme, trumpets and then trombones anticipate the second theme, to the accompaniment of rata-tat, eighth in woodwinds, just as easy as you please. The second theme enters in violins without any preparation, as if it were a natural consequence of the angry first theme, played softly and trippingly it without any change in tempo. It is a complete contrast with the distempered first theme, sounding like a bit of drollery, especially because it begins with the same rising to note upbeat with which the first theme begins. It seems to catch itself quickly before just continuing on with the first theme. Now the character of the music changes markedly, the key shifts to F major, and in place of the jagged stridency of the first subject, we hear a charming prominent, lightly and delicately sauntering along in the same tempo was the first subject as if without a care in the world.

Beware this innocent little tune, for it carries the seeds of the first subject within it. For it is fashion from motive one and the exercise like figuration implanted into the first theme. Both are rhythmically altered to appear tamer and more naive. This simple little theme can be likened to the landler theme from the second movement that tried to stand his ground against the combat of waltz. Once again, Mahler hints at the finale by including a turn figure in the new theme. The use of the seventh interval during the development of the second theme is important for his comic effect. During the second themes progress, Mahler injects a note of parity that recalls the minuet theme from the scherzo of the sixth Symphony. A wicked little E flat clarinet has a go at the theme briefly. Grace notes attached to falling octaves, or offbeat eighth’s with increasingly wider more dissonant intervals, so he scraps of shaking figuration both from the first subject and the waltz theme of the second movement, and a walking bass, all combined to make the second theme suspiciously caricaturesque. In its light-hearted frivolity, it might be compared to the old fatherish minuet of the Sixth Symphony, scarcer movement, played in march time, and the jolly Pan march from the first movement of the Third Symphony. When the second theme suddenly threatens to become more aggressive its opening dactylic figure is misshapen by extremely wide leaps, horns heave a mighty blast of E flat, that blows away the theme, ushering in the reprise of the first subject, now in a flat minor.

The return of the first subject is unexpected, giving us a jolt even though the tempo remains constant, the entire orchestra gives vent to the scherzo fury. A quarter note triplet variant of motive two makes it sound even more adamant in its destructive resolve. Again, contrapuntal lines swirl about wildly as sections of the orchestra play off each other on various elements of the first subject. A cascading chromatic descent in woodwinds leads back to the second part of the first theme, based upon a conjunction of motives three and one played resolutely by strings. horns join in with the triadic variation of the themes second part, heard earlier in trombones and tuba, trombones enter on the first part of the theme, against a four-note descending scale and clarinets, that is an elongated version of a fragment of the theme second part. Frequent descending phrases during the extensive development of the first subject seem to drag the music downward, making it sound even more sinister than before. When the first theme reappears full of fire and brimstone, in oboes, clarinets, and trumpets, violins quietly play an inverted version of the falling phrase heard earlier in the clarinets that sounds like the beginning of the Meister march theme from the finale of the Seventh Symphony. Later violins invert this phrase as part of the continuing development of the first subject, giving it the shape, though not the character of the upward arching motive of redemption, which here sounds uncharacteristically menacing, this negative transformation of redemption might symbolize its converse damnation, befitting its role in the upcoming middle section.

At this point, the orchestra thins out, and fragments of the main theme become attenuated, until a muted trumpet focuses attention on a dotted rhythmic tattoo on falling fourths, that Mahler also used in the Pan march from the third symphonies opening movement. This trumpet tattoo heralds the reprise of the second theme whose two note Upbeat overlaps with it. Here’s the entire reprise of the first subject.

Once again, the quaint little sauntering tune returns just as ambivalent and unconcerned about the aggressive first theme, as it had been earlier. The emphatic upbeat with which the theme begins is immediately dampened by a sudden decrease in dynamic level to the piano, which abruptly changes the character of the music from the harsh brutality of the first subject to the lightheartedness of the second triangle and glockenspiel make the bouncy second theme sound gay or in more festive. As it continues on its merry way, the theme is given greater impulse by 16th note shakes, and the walking bass figure heard earlier, horns enter with a strident, almost pompous version of the second theme, and add to it material from the third symphonies Pan March.

Then the whole orchestra takes up this new version of the second theme, and develops it in tripartite counterpoint, until trombones enter menacingly with the damnation motive. For a second time, the trombones try to divert the course of the second theme with this motive. But the theme continues along oblivious to the ominous sounds of damnation, leering in the background, as if waiting for just the right moment to pounce. That moment comes rather quickly has the horns thrust aside the second subject with a mighty blast of the damnation motive, and the first theme re-enters savagely in low strings.

Soon oboes and first violins enter forthrightly with a new melody, principally composed of a turn figure, followed by an upward leap of a ninth. This new version of the first theme will appear in many different guises during the middle section, and be transfigured as part of the first theme group in the finale.

The new version of the first theme combines with the damnation motive in low winds and strings, against scraps of the original first theme in the second violins and violas. These contrasting elements are shifted around the orchestra in a kaleidoscopic effect that reconfigures every nine measures. Soon the orchestra reduces to a chamber ensemble of oboes, clarinets, and violins, a cymbal crash abruptly intrudes and clears the air leaving but a soft high A in tremolo strings, and flutter tongue flutes that chills the atmosphere. The tonality shifts to D major, the key of the opening movements tender first theme, and the frenzy of the first subject and the flippancy of the second completely eliminated. Another blast of the damnation motive and the horns fails to dispel the sense of peace and calm that has suddenly descended over the music. A solo trumpet softly and tones the new version of the first theme that was first stated so harshly by violins after the first subjects most recent reprise, the combination of a turn figure and an inverted variant of motive one sounds strangely comforting, nothing like how it will sound when metamorphosed into a fervent prayer in the finale.

With its first transformation, we enter into the heavenly serenity of the middle section, comprised of a series of variations on this Adagio theme, played primarily by solo instruments, accompanied by a substantially reduced orchestra.

The complex counterpoint of the first subject has vanished, someone haltingly, the theme undergoes a complete transformation. Its drawl humor is gone for now, it sounds like a soothing lullaby, a perfect counterfoil for the intensity and violence of the first subject, and the carefree senseless second, after the melody undergoes development, the damnation motive reappears like a dreadful specter threatening to jolt us out of the tender reverie of the common Adagio theme. It is important to notice the relationship between the damnation motive and the first four nodes of the Adagio theme. The only difference between them is the length of the first rising interval. Although the music tries to build to a cadence that would do away with the peaceful Adagio theme, and ascending string glissando, waves it away, and brings in a variation of that theme, again in a solo trumpet, apparently undisturbed by the intrusions of the damnation motive, thence the Adagio theme develops in stretto, adding an elongated version as a countersubject.

Once again, the music builds on a crescendo that is cut off by a rising violin glissando ushering in the return of the Adagio theme, now played in stretto, and winds and strings. This time, the rising ninth with which the theme originally ended, is omitted, and the falling interval that preceded it lengthens from a fourth to a seventh. As the Adagio theme develops, it builds on a crescendo in the entire orchestra, which is the only time the orchestra is full forces are used during the middle section, but hopes for fulfillment are dashed on a super octave plunge and the violins thereafter, the Adagio theme quickly scattered around the orchestra with why downward leaps and stretched turn figures overlapping the themes original version. Suddenly, muted brass forced their way in with a dissonant Neapolitan sixth chord that is reminiscent of the opening quarter of the six symphonies finale. Yet again, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, and ascending glissando and violins and harp brings back the hushed string tremeloes that open the middle section.

The reappearance of the string tremeloes would appear to be a signal for the return of the soothing Adagio theme. But what follows quickly negates that assumption. The dark sounds of damnation uttered by oboes and english horn over nebulous harmonies and other woodwinds heralds something entirely different. Immediately after the damnation mode of concludes obnoxiously loud clarinets were allowed a perverse to bar phrase that contains a turn figure, followed by a stretched inversion of the movements opening motive one echoed in part by flute and violins over a hint of the scherzo’s first subject and impish E flat clarinet squeals out this shrill version of the Adagio theme, played twice as fast as the original, with sarcastic mockery, as if it was a demonic response to the soothing serenity of the original is followed immediately in flutes and violins by two measures of the turn figure, and a fragment of the first theme, hinting at is reprise this brief reference to the opening scherzo quickly fades on an ascending harp glissando that brings back the violin tremeloes this time on a high F natural that hints at B flat major, an important key in the first movement, woodwinds threaten with the damnation mode, successfully warding off the return of the original Adagio theme, in its place the E flat clarinet repeats its grotesque version of that theme, followed again by the same scrap of music from the first subject that succeeded a moment ago. Mahler repeats this procedure yet again, the harps rising glissando shuts off the brief reference to the first subject, and brings back the violin tremeloes.

But again, the tremeloes fail to bring back the Adagio feet. Instead, the damnation motive returns and leads to more rhythmic fragments of the first theme, whispered and muted violins and brass, as if trying to sneak in for the kill. Another harp glissando cuts them off, and again brings back violin tremeloes and oboe tries to replay the original version of the Adagio theme, but it is rudely interrupted by a clarinet that arrogantly blasts out the first theme. Other woodwinds join the clarinet with additional elements of that theme until another ascending harp glissando holds this attempt to reinstate the first subject. Instead, it brings back not only the violin’s tremeloe, but also the original version of the Adagio theme. Here played in a dialogue between a trumpet and mid-range strings, sounding like a great sigh of resignation, and elongated version of this tender theme wells up in the strings against the woodwinds flippant version. Together, they extend this sequence into a bridge passage that leads to the reprise of the first subject. While the pace remains unchanged during this transition, it takes on the character of a stolid March played softly at first, but becoming increasingly menacing, a harp plays an augmented and inverted variant of motive one, the tail end of the Adagio theme, concluding with different rising leaps at each repetition. This seemingly innocuous music takes an ominous turn when fragments are the first subject sneak in quietly, first in strings and then in winds, they seem to tiptoe incautiously, as if not to arouse the harp that has previously staved off the return of the first subject. Soon the atmosphere darkens in anticipation of the worst. Crossing thematic fragments and strings continued to interject softly bassoons tried to force in motive three from the first subject, while flutes sneak in a bit of the figuration from the first theme, intertwined with the faithful damnation motive on other winds. The strings catch on extending the first subject a bit further, with a sinister pronouncement of the damnation motive in muted horns the violin first theme rashly forces its way in jolting us out of the dream world of the middle section, trombones, and low strings Russian like thunderbolts, with the turbulent theme, now played as if for the vengeance. The full orchestra takes part in celebrating the first subject’s triumphant reprise. Again rhythmic and motivic elements of the demonic first subject return and are intricately interwoven in complex polyphony. a dactylic rhythmic figure taken from the first scherzo theme turns into the wicked motive of the devil’s dance in woodwinds embellished with trills. It is in contrast with its retrograde inversion, played twice as slowly by the horns with bells up fanfares and trombones and to book project little of their heroic character in the midst of this increasingly turbulent music, when the full orchestra asserts the second part of the first theme, beginning with the rising mode of three, low woodwinds and brass counter with a sharply articulated descending scale, that recalls the motive spear from Wagner’s ring cycle. Its downward motion contrasts with the rising thematic material, fiercely pulling the music in opposite directions.

Even the puckish variation of the first subject heard during the opening section returns here, joined with skipping rhythms and woodwinds and sounding more wickedly impish than innocently playful.

Throughout the lengthy reprise of the first subject, its themes undergo continuous development, thematic and motivic fragments flit about chaotically from one section of the orchestra to another. Mahler integrates the principal motives, with thematic figures taken from earlier symphonies, woodwinds play mode of two, at the same time as lower strings have motive one, both fitting together as if they were kin, which of course they are. The diatonic version of motive three also returns and violas and second violins answered in the next measure by the devilish laughter have stopped horns. Strings keep repeating the dactylic rhythm that permeates the first theme while horns and trumpets vulgarly wag their tongues, thematic fragments are distorted virtually beyond recognition it is a dance macabre like no other in Mahler’s music.

When the first two notes of the damnation motive sound forcefully in winds and violins, rising threateningly on an augmented second, the first theme forces its way in again, even more frantically than before, twice more the first two notes of the menacing damnation motive intercede, urging on the increasing frenzy of the first subject. Each time the first subject re-enters, after these two powerful brass chord sounds, it becomes more energetic as well as more maniacal. Finally, during the closing measures of the coda, the first theme becomes so frenzied that it threatens to run amok.

Single measure orchestral explosions burst out with increasing frequency as the first subject rages on uncontrollably. Motives one and two are repeated incessantly as if bordering on madness. Through the welder of sound, we can just make out a grotesque version of the damnation motive. Now on two falling fifths played by four horns. Finally, the movement ends virtually as it began, with the three basic motives played at the beginning, cut off just as they threatened to start this insane music over again on motive one. Mahler also ends the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony by bringing back the motive with which it began, a motive that relates to motive one. This is yet another example of the importance of eternal return in Mahler’s music.

After this wild music ends, we are grateful for a moment’s peace. But the events that we have witnessed in this rondo burlesque, and the two movements that preceded it are so destructive of the positive human spirit, that we seem bereft of all that is worth preserving in this life. What other response could one make to the destructive onslaught of this infuriating music, then a fervent prayer for redemption? In the finale, Mahler offers such a prayer in what he had good reason to believe would be his last complete work.

By Lew Smoley