- Profession: Composer, pianist.

- Residences: Graz, New York City.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 20-10-1894 Year 1894 Hamburg: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 16-06-1895 Year 1895 Steinbach: Letter by to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 17-08-1895 Year 1895 Steinbach: Letter by to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 15-10-1895 Year 1895 Location unknown: Letter to to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 02-11-1895 Year 1895 Hamburg: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 05-11-1895 Year 1895 Hamburg: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 12-06-1896 Year 1896 Steinbach: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 21-06-1896 Year 1896 Steinbach: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 11-07-1896 Year 1896 Steinbach: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 26-11-1897 Year 1897 Vienna: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 11-04-1898 Year 1898 Vienna: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 04-06-1898 Year 1898 Vienna: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- 30-07-1898 Year 1898 Vahrn: Letter to Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

- Born: 01-04-1866, Empoli, Italy.

- Died: 27-07-1924, Berlin, Germany.

- Buried: Schoneberg cemetery. Friedhof Schöneberg III, Friedenau, Tempelhof-Schöneberg, Berlin, Germany. The first gravesite inside the front gate.

- 22-10-1894 Year 1894 c065. 1894 Concert Hamburg 22-10-1894 (piano).

- 19-03-1899 Year 1899 c112. 1899 Concert Vienna 19-03-1899.

- 18-03-1900 Year 1900 c125. 1900 Concert Vienna 18-03-1900.

- 22-05-1905 Year 1905 c177. 1905 Concert Strasbourg 22-05-1905.

- 06-01-1910 Year 1910 c235. 1910 Concert New York 06-01-1910.

- 07-01-1910 Year 1910 c236. 1910 Concert New York 07-01-1910.

- 08-01-1910 Year 1910 c237. 1910 Concert Brooklyn 08-01-1910.

Ferruccio Dante Michelangelo Benvenuto Busoni was an Italian composer, pianist, conductor, editor, writer, and piano teacher. Ferruccio Busoni was born in the Tuscan town of Empoli, Italy, the only child of two professional musicians. His father, Ferdinando, was a clarinetist. His mother, Anna, was a pianist from Trieste. They were often touring during his childhood, and he was brought up in Trieste for the most part. Busoni was a child prodigy. He made his public debut on the piano with his parents, at the age of seven. A couple of years later he played some of his own compositions in Vienna where he heard Franz Liszt play, and met Liszt, Johannes Brahms and Anton Rubinstein.

Busoni had a brief period of study in Graz with Wilhelm Mayer (who published his own compositions under the pseudonym of W. A. Rémy and also taught Felix Weingartner) and was also helped by Wilhelm Kienzl, who enabled him to conduct a performance of his own composition Stabat Mater when he was twelve years old, before leaving for Leipzig in 1886 where he studied with Carl Reinecke (a former pupil of Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann). He subsequently held several teaching posts, the first in 1888 at Helsinki, where he met his wife, Gerda Sjöstrand, the daughter of Swedish sculptor Carl Eneas Sjöstrand, and began a lifelong friendship with Jean Sibelius.

In 1890 he won the Anton Rubinstein Competition with his Concert Piece for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 31a. He taught in Moscow in 1890, and in the United States from 1891 to 1894 where he also toured as a virtuoso pianist. In 1894 he settled in Berlin, giving a series of concerts there both as pianist and conductor. He particularly promoted contemporary music. He also continued to teach in a number of masterclasses at Weimar, Vienna and Basel; among his pupils were Egon Petri and Stanley Gardner.

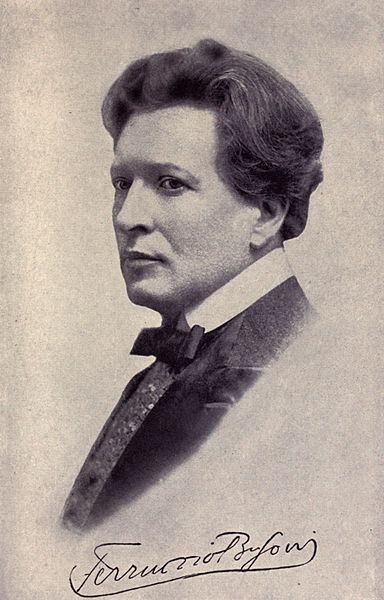

Ferruccio Busoni (ca. 1895).

In 1907, he penned his Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, lamenting the traditional music “lawgivers”, and predicting a future music that included the division of the octave into more than the traditional 12 degrees. His philosophy that “Music was born free; and to win freedom is its destiny,” greatly influenced his students Percy Grainger and Edgard Varèse, both of whom played significant roles in the 20th century opening of music to all sound.

During World War I, Busoni lived first in Bologna, where he directed the conservatory, and later in Zürich. He refused to perform in any countries that were involved in the war. He returned to Berlin in 1920 where he gave master classes in composition. He had several composition pupils who went on to become famous, including Kurt Weill, Edgard Varèse, Friedrich Löwe, Aurelio Giorni and Stefan Wolpe.

Other notable Busoni pupils included Egon Petri, Alexander Brailowsky, Natalie Curtis, Maud Allan (the famous dancer), Michael von Zadora, Louis Gruenberg, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Beryl Rubinstein, Edward Steuermann, Dimitri Tiomkin, Rudolf Ganz, Lloyd Powell, Herbert Fryer, Augusta Cottlow, Leo Kestenberg, Gregor Beklemischeff, Leo Sirota, Edward Weiss, Theophil Demetriescu, Theodor Szántó, Gino Tagliapietra, Gottfried Galston, Otto Luening, Gisella Selden-Goth, Philipp Jarnach, Vladimir Vogel, Guido Guerrini, Woldemar Freeman, and Robert Blum.

Busoni died in Berlin from a kidney disease. He was interred in the Städtischen Friedhof III, Berlin-Schöneberg, Stubenrauchstraße 43-45. He left a few recordings of his playing as well as a number of piano rolls. He was an atheist. His compositions were largely neglected for many years after his death, but he was remembered as a great virtuoso and arranger of Bach for the piano. Around the 1980s there was a revival of interest in his work. He is commemorated by a plaque at the site of his last residence in Berlin-Schöneberg, Viktoria-Luise-Platz 11, and by the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition.

Busoni died officially from heart failure, although inflamed kidneys and overwork also contributed to his death. Doktor Faust remained unfinished at his death and was premiered posthumously in Berlin in 1925 in a completion made by Jarnach. Busoni’s Berlin apartment was destroyed in an air-raid in 1943, and many of his possessions and papers were lost or looted. A plaque at the site commemorates his residence. Busoni’s wife Gerda died in Sweden in 1956. Their son Benni, who despite his American nationality had lived in Berlin throughout World War II, died there in 1976. Their second son Lello, an illustrator, died in New York in 1962.

Music

Most of Busoni’s works are for the piano. Busoni’s music is typically contrapuntally complex, with several melodic lines unwinding at once. Although his music is never entirely atonal in the Schoenbergian sense, his mature works, beginning with the Elegies, are often in indeterminate key. He was in contact with Schoenberg, and made a ‘concert interpretation’ of the latter’s ‘atonal’ Piano Piece, Op. 11, No. 2 (BV B 97), in 1909. In the program notes for the premiere of his own Sonatina seconda of 1912, Busoni calls the work senza tonalità (without tonality). Johann Sebastian Bach and Franz Liszt were key influences, though late in his career much of his music has a neo-classical bent, and includes melodies resembling Mozart’s.

Some idea of Busoni’s mature attitude to composition can be gained from his 1907 manifesto, Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, a publication somewhat controversial in its time. As well as discussing then little-explored areas such as electronic music and microtonal music (both techniques he never employed), he asserted that music should distill the essence of music of the past to make something new.

Many of Busoni’s works are based on music of the past, especially on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach (see below). The first version of Busoni’s largest and best known solo piano work, Fantasia contrappuntistica, was published in 1910. About half an hour in length, it is essentially an extended fantasy on the final incomplete fugue from Bach’s The Art of Fugue. It uses several melodic figures found in Bach’s work, most notably the BACH motif (B flat, A, C, B natural). Busoni revised the work a number of times and arranged it for two pianos. Versions have also been made for organ and for orchestra.

Ferruccio Busoni with his dog.

Busoni used elements of other composers’ works. The fourth movement of An die Jugend (1909), for instance, uses two of Niccolò Paganini’s Caprices for solo violin (numbers 11 and 15), while the 1920 piece Piano Sonatina No. 6 (Fantasia da camera super Carmen) is based on themes from Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen.Busoni also drew inspiration from non-European sources, including Indian Fantasy for piano and orchestra. It was composed in 1913 and is based on North American indigenous tribal melodies drawn from the studies of this native music by ethnomusicologist, Natalie Curtis Burlin.

Busoni was a virtuoso pianist, and his works for piano are difficult to perform. His Piano Concerto, Op. 39 (1904) is one of the largest such works ever written. Performances generally last over seventy minutes, requiring great stamina from the soloist. The concerto is written for a large orchestra with a male voice choir that is hidden from the audience’s view in the last movement. British pianist John Ogdon, one of the champions of the work, called it “the longest and grandest piano concerto of all.” (However, it was not the first piano concerto to include a chorus, as is often assumed; Daniel Steibelt wrote a similar work in 1820.)

Busoni’s Turandot Suite (1905), probably his most popular orchestral work, was expanded into his opera Turandot in 1917, and Busoni completed two other operas, Die Brautwahl (1911) and Arlecchino (1917). He began serious work on his best known opera, Doktor Faust, in 1916, leaving it incomplete at his death. It was then finished by his student Philipp Jarnach, who worked with Busoni’s sketches as he knew of them, but in the 1980s Antony Beaumont, the author of an important Busoni biography, created an expanded and improved completion by drawing on material that Jarnach did not have access to.

Aesthetics

Busoni’s music can be considered in the context of his three major aesthetic beliefs: essence, oneness and junge Klassizität (literally ‘young classicism’). The essence of music suggests that music is free from any prescriptive labels; in other words, it is absolute. For example, Busoni asked us to question just what it was in a piece of instrumental church music, that was inherently ‘church’. The oneness of music proposes that music is free from prescriptive devices, and that there are endless possibilities of composition. Finally, in his words, junge Klassizität (often mistaken for neo-classicism) included ‘the mastery, the sifting and the turning to account of all the gains of previous experiments and their inclusion in strong and beautiful forms’ (Busoni, ‘Letter to Paul Bekker’, 1920).

His music falls in that most fractious of periods, the fin de siècle, where chromatic elements became part of the structure of the music, rather than being decoration. By studying Busoni’s aesthetic beliefs we can suggest that his music is metatonal – given that he sought to include the old with the new to create limitless compositions. This is not to suggest (as Pfitzner did, when he attacked The Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music by Busoni) that his music is without form, nor is it without any sense of tonality (a common mistake when one finds oneself between Classical and Serial music). This grey area of music history is more engaging because the traditional forms and pitch structures have taken a side road, a road that did not ultimately lead to serialism.

In order to understand Busoni’s compositions one should take only what is given in the music, and interpret them through his aesthetic beliefs (though this is no easy task, and the everpresent binarism between what a composer says and what a composer does should be kept in mind). Busoni can be recognised as a man with a variety of musical abilities. He wrote compositions and libretti, performed as a concert pianist, transcribed pieces by other composers (such as Bach, Mozart and Liszt), taught master classes, and produced aesthetic writings. It is to this end that Busoni considered music a fusion of disciplines, or to use his words ‘to recognise the whole phenomenon of music as ‘oneness’. (Busoni, ‘The Essence of Oneness of Music’, 1921).

Editions and transcriptions

Busoni edited and transcribed works by other composers, in particular those of Bach, Liszt, and Mozart.

The best known of these is his edition of the solo keyboard works of Bach, which he edited with the assistance of his students Egon Petri and Bruno Mugellini. He adds tempo markings, articulation and phrase markings, dynamics and metronome markings to the original Bach, as well as extensive performance suggestions. Their influence on the history of Bach performance should not be underestimated, as Chiara Bertoglio has pointed out. In the Goldberg Variations (BV B 35), for example, he suggests cutting eight of the variations for a “concert performance”, as well as substantially rewriting many sections. The edition of the Goldberg Variations remains controversial, but has recently been reprinted. Its world premiere recording was by Sara Davis Buechner (aka David Buechner).

He created many other piano transcriptions of Bach works, including the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (BV B 29, no. 2) (originally for organ) and the Chaconne (BV B 24) from the Partita No. 2 in D minor for solo violin, BWV 1004. Busoni became so well known as a transcriber of Bach’s pieces, that the name “Bach-Busoni” was sometimes mistaken for his surname, and on one occasion his wife was introduced to someone as “Mrs. Bach-Busoni”.

He edited three volumes of the 34-volume Franz Liszt Stiftung edition of Liszt’s works, including most of the etudes. The Liszt edition was a scholarly endeavor and was faithful to the originals, but Busoni also prepared more freely adapted versions intended for concert performance, including transcriptions of the Paganini-Liszt etudes. The most famous of these is La Campanella (BV B 68), which has been championed by pianists such as Ignaz Friedman and Josef Lhévinne, and more recently by John Ogdon. Another famous transcription is his piano arrangement of Franz Liszt’s organ work Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam” (BV B 59). On a smaller scale, Busoni edited works by Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Schoenberg and Schumann.

In the last seven years of his life Busoni worked sporadically on the Klavierübung, a compilation of exercises, transcriptions, and original compositions of his own, with which he hoped to pass on his accumulated knowledge of keyboard technique. It was issued in five parts between 1918 and 1922, and a second edition was published posthumously in 1925.

He was planning to play some of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words in a series of recitals in London in the year of his death.

Recordings by Busoni

His recorded output on gramophone record was very limited, and many of the original recordings were destroyed when the Columbia factory burnt down. The following pieces (recorded for Columbia) survive from February 1922:

- Bach: Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C major (The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1).

- Bach-Busoni: Organ Chorale Prelude “Nun freut euch, lieben Christen”.

- Beethoven-Busoni: Ecossaises.

- Chopin: Étude in G-flat major, Op. 10, No. 5.

- Chopin: Étude in E minor, Op. 25, No. 5.

- Chopin: Nocturne in F-sharp major, Op. 15, No. 2.

- Chopin: Prelude in A major, Op. 28 No. 7.

- Chopin: Prelude in A major, Op. 28 No. 7, and Étude, Op. 10, No. 5 (connected by an improvisatory passage).

- Liszt: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 13 (abbreviated to fit it on two sides of a 78 record).

- Liszt: La Campanella

Piano rolls

Busoni made a considerable number of piano rolls, and a small number of these have been re-recorded onto vinyl record or CD. The value of these recordings in ascertaining Busoni’s performance style is a matter of some dispute. Many of his colleagues and students expressed disappointment with the recordings and felt they did not truly represent Busoni’s pianism. His student Egon Petri was horrified by the piano roll recordings when they first appeared on LP and said that it was a travesty of Busoni’s playing. Similarly, Petri’s student Gunnar Johansen who had heard Busoni play on several occasions, remarked, “Of Busoni’s piano rolls and recordings, only Feux follets (Liszt’s 5th Transcendental Etude) is really something unique. The rest is curiously unconvincing. The recordings, especially of Chopin, are a plain misalliance”.

In 1950 Columbia Records released five individual long playing records entitled Great Masters of the Keyboard. They were designated Volume I, II, III, IV, and V. The records were sourced from piano rolls made by Welte-Mignon of Germany. Volume II (ML 4292) featured Busoni on side one. He plays three pieces: 1) Paganini-Liszt: La Campanella (Etude No. 3); 2) Chopin: Prelude No. 15 in D-flat Major, Op. 28 (“Raindrop”); 3) Beethoven-Liszt: Fantasia on “Ruins of Athens”. The liner notes refer to Busoni as “One of the towering pianists of all time.”