- Profession: Businessman, journalist and conductor

- Relation to Mahler: He was owner of Manuscript Symphony No. 2.

- Correspondence with Mahler: No

- Born: 03-03-1941 New York, America

- Died: 01-01-2016 New York, America. Aged 74.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Unknown

Gilbert Edmund Kaplan, who amassed a fortune on Wall Street that enabled him to fulfill his fantasy of becoming an orchestral conductor, confining himself to a single work, Mahler’s Second Symphony, but stunning a skeptical musical world with his command of the daunting score, died 01-01-2016 in New York City. The passion dated to one day in 1965, when Mr. Kaplan, still toiling on Wall Street, accompanied a friend to New York City’s Carnegie Hall to hear a rehearsal of Mahler’s Second Symphony by the American Symphony Orchestra, under the venerable conductor Leopold Stokowski.

The composition is regarded as a monument of 19th-century music, a sprawling work of five movements requiring an orchestra of 100, a choir of up to 200 and two soloists. Running as long as 90 minutes in performance, it leads the listener on a transcendent exploration of the meaning of life and death. “And that was it,” Mr. Kaplan told the Boston Globe in 1989. “Zeus threw the bolt of lightning. I walked out of that hall a different person. There’s been nothing that put me in orbit the way this did.”

Mr. Kaplan dove into an all-consuming study of the composition and woke up on the cusp of his 40th birthday, he said, fixated on the notion that he must conduct it – the only way, he thought to “unlock the mystery.” He floated the idea among friends, who told him it was “insane.” “They were right, of course,” he told the Globe. “I tried to read a book on conducting and couldn’t understand it, though I consoled myself with the thought that if I tried to read a book on tying a shoelace, I probably couldn’t understand that, either.”

Later, Mr. Kaplan hopped around the world attending performances of the symphony and meeting with conductors including Zubin Mehta, James Levine and Georg Solti. “What a pleasure it is to meet a man from Wall Street with whom I talk about music,” Mr. Kaplan recalled Solti remarking, “because when I meet my colleagues all I talk about is money.”

In 1982, after a series of rehearsals, Mr. Kaplan hired the American Symphony Orchestra to present the Second Symphony under his baton at Lincoln Center. Estimates of the price tag of the affair, an invitation-only celebration of the 15th anniversary of Institutional Investor, reached $100,000. The orchestra, evidently skeptical of Mr. Kaplan’s abilities, placed two conditions on the performance: no tickets would be sold to the public, and there would be no media reviews. Even Mr. Kaplan seemed to harbor doubts about his preparedness. If the performance derailed, he planned to pivot on the podium and tell his audience, “Ladies and gentlemen, dinner is served.”

Despite the ban on reviews, Leighton Kerner, classical music critic for the Village Voice, was in the audience made up mainly of Wall Street celebrities, along with at least one senator and two prime ministers. He declared the interpretation “one of the five or six most profoundly realized Mahler Seconds” in the previous 25 years.

Even those attendees not schooled in music seemed to recognize that they had witnessed something remarkable. “I had the feeling,” he told the London Evening Standard, “that people in the audience were urging me to fulfill my dream because each of them had a secret ambition. They were up with me that night, playing baseball for the Yankees, writing the book they never wrote, getting the girl they never got.” Encouraged, perhaps even emboldened, by the evening’s success, Mr. Kaplan went forward with his Mahlerian devotion.

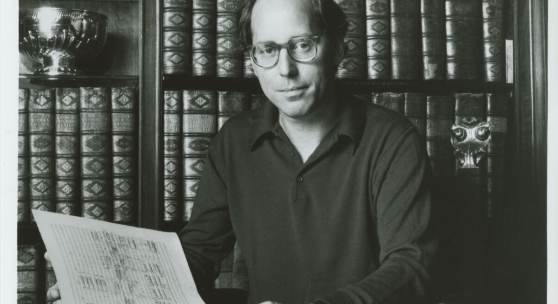

Gilbert Kaplan (1941-2016) with Manuscript Symphony No. 2.

More than 50 orchestras around the world engaged Mr. Kaplan, among them the Vienna Philharmonic, the London Philharmonic, the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic, the China National Symphony Orchestra, the orchestra of La Scala opera house in Milan and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Mr. Kaplan’s recording of the Second Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra was described in news accounts as the best-selling Mahler recording ever. He had his detractors. In 2008, when he conducted the New York Philharmonic in a performance marking the centennial of the Second Symphony’s premiere in the United States, some members of the orchestra complained about his leadership of the work, decrying him as an “impostor” and a “charlatan.” Steve Smith, who reviewed the event for the New York Times, seemed to disagree. “Every gesture had purpose and impact, and the performance as a whole had an inexorable sweep,” he wrote. “To think there is nothing else to know of Mahler’s Second beyond what Mr. Kaplan has to show would be a mistake. But it seems likely that no one is better equipped to reveal the impact of precisely what Mahler put on the page.” It was that fidelity to Mahler’s original intent that perhaps conferred on Mr. Kaplan all the authority that he possessed. “I feel that I’m always working for Mahler,” he told the London Guardian in 2003. “Apart from tempo, I don’t ask the orchestras I conduct to follow my interpretation. I ask them to observe what Mahler wrote, and on most everything I don’t lose an argument because it’s in the score.”

Gilbert Edmund Kaplan was born in New York City on March 3, 1941. A late brother was Joseph Brooks, the jingle writer who also penned the pop hit “You Light Up My Life.” Mr. Kaplan took piano lessons as a boy but, disinclined to practice, did not seem destined for a life in music. He studied economics at Duke University before graduating from the New School in New York City in 1964. Survivors include his wife of 45 years, the former Lena Biörck of New York, for whom he purchased the ring that Mahler had once given to his wife, Alma; four children, Kristina Wallison and Claude Davies, both of New York, and John Kaplan and Emily Kaplan, both of Los Angeles; and eight grandchildren.

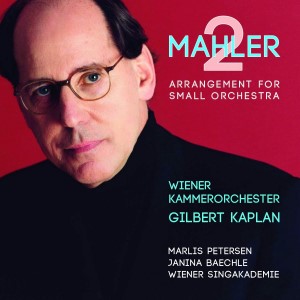

Album Gilbert Kaplan (1941-2016).

Mr. Kaplan, who conducted from memory and with a baton owned by Mahler, accepted no payment for his performances because he did not consider himself a professional. Among other confessed weaknesses, he could barely read music apart from the Second Symphony. He was, he said, an amateur “in the best sense of the word.” “I didn’t set out to do it because I had some grandiose ambition to be a conductor,” he once told an Australian newspaper. “I did it because I wanted to get inside the music? There’s a real explanation of life and death in that music and I wanted to get to the bottom of it.”

In 1984, he purchased from a foundation the original Manuscript Symphony No. 2. After rigorously comparing the original with the commonly used version, he claimed to have found 300 errors in the latter and co-edited a new score that won the approval of the International Gustav Mahler Society in Vienna. As word traveled in the music community of Mr. Kaplan’s achievements, he became a sought-after scholar and conductor of Mahler, although, with few exceptions, he limited his conducting appearances to the Resurrection. See Manuscript Symphony No. 2.

Gilbert E. Kaplan, the publisher of a monthly financial magazine who attracted widespread attention in 1982 by learning and conducting Mahler’s mammoth ”Resurrection” Symphony, has taken his fascination with the work one step further by acquiring the composer’s original manuscript of the score.

Mr. Kaplan plans to leave the manuscript on loan at the Pierpont Morgan Library so that Mahler scholars can have access to it, he said in a telephone interview Friday. The holdings of the Morgan Library and other collections housed there include several important Mahler autographs.

Mr. Kaplan purchased the score last week in Zurich from the Willem Mengelberg Foundation. Mengelberg, a famous Dutch conductor and champion of Mahler, was given the score by the composer’s widow in 1920 on the occasion of a Mahler festival led by Mengelberg with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam.

The purchase price was not disclosed, but a score of Mahler’s First Symphony in which only 22 pages were in the composer’s own hand was recently sold by Sotheby’s for approximately $200,000. Informed sources said the price would have been nearly twice as much if that score had been completely autograph, as the one purchased by Mr. Kaplan is. Maintaining Mengelberg Collection

The funds realized through the sale of the symphony score will be used for maintaining the Mengelberg collection of scores and memorabilia and the late conductor’s 17th-century farm and villa in Switzerland, according to a spokesman for the foundation.

This one symphony, composed between 1888 and 1894, has been the sole subject of Mr. Kaplan’s unusual conducting career. Fascinated with it since his early 20’s, he decided at the age of 40 to undertake intensive training, hire an orchestra and conduct the work.

”I can’t explain,” Mr. Kaplan said, ”it’s like falling in love.”

He found a teacher, jetted around the world to consult other conductors and, to hear the work as often as possible, studied recordings and eventually led the symphony from memory before an invited audience in Avery Fisher Hall in September 1982.

Mr. Kaplan is the publisher of Institutional Investor, and also is now chairman of the board of the American Symphony Orchestra, the orchestra he hired for his debut in 1982.

Since then he has led the ”Resurrection” (the second of Mahler’s symphonies) again with the American Symphony Orchestra and with the new Japan Philharmonic Orchestra in Tokyo. He has engagements to conduct it in November with the Buffalo Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra in London and Wales in December. Doesn’t Feel Qualified

Mr. Kaplan has no current plans to broaden his repertory. ”Professional conductors tell me I could, but I don’t feel qualified,” he said. ”I don’t read music all that well.”

Mr. Kaplan’s preparation for his conducting venture included visits to examine the manuscript in The Hague Museum where it was previously housed. ”In the printed score,” he said, ”you can read Mahler’s instructions, but only in the autograph can you see the intensity with which he wrote them.”

As an example Mr. Kaplan singled out a passage where Mahler instructs the conductor to change the time- beating pattern from four to two beats in each measure. ”He wrote it in letters two inches high,” Mr. Kaplan said. ”You can see he really wants you to do it.”

In the course of negotiations for a facsimile edition of the manuscript, Mr. Kaplan was offered a chance to acquire it. He now intends to publish a facsimile himself later this year.

Mr. Kaplan plans to deliver his new treasure to the Morgan Library sometime later this week. But first he wants to keep it close by in his East Hampton house for a while. ”I’ve really never had enough time with it, you know – there’s no end to the time you can spend with this score.”

Kaplan Foundation

The Kaplan Foundation is a foundation dedicated to the scholarship and preservation of the music of Gustav Mahler set up by amateur conductor and businessman Gilbert Kaplan.

The Kaplan Foundation has published facsimile editions of Mahler’s autograph manuscript of the Second Symphony, the Adagietto movement of the Fifth Symphony and the song, “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen.”

It has produced Mahler Plays Mahler, a recording using piano rolls that Mahler made of his own compositions. These rolls are the only documents that exist of Mahler as a performer.

The Foundation has also published Mahler Discography (together with editor Pèter Fülöp), a definitive guide to 2,774 recordings of Mahler’s music; Mahler’s Concerts, by Knud Martner, a compilation of the 323 known performances led by Mahler as a conductor or pianist; and The Mahler Album (editor Gilbert Kaplan), an award-winning illustrated biography containing all known photographs and a selection of drawings and sculptures of the composer.

Together with Universal Edition (UE) music publishers, the Foundation is co-publisher of two scores of Mahler’s Second Symphony: the New Critical Edition (editors Renate Stark-Voit and Gilbert Kaplan) and the Arrangement for Small Orchestra (by Gilbert Kaplan and Rob Mathes); and with Peters music publishers, co-publisher of the New Critical Edition of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony.

The Kaplan Foundation is located in New York City.