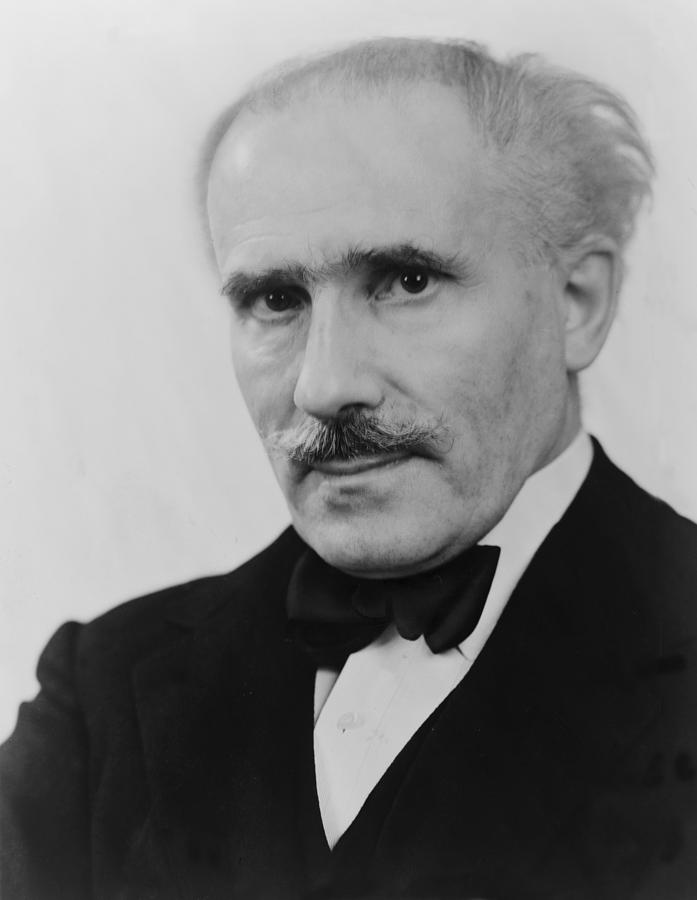

- Profession: Cellist, conductor.

- Residences: Italy, New York City.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 25-03-1867 Parma, Italy.

- Died: 16-01-1957 New York, America.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Cimitero Monumentale, Milan, Italy

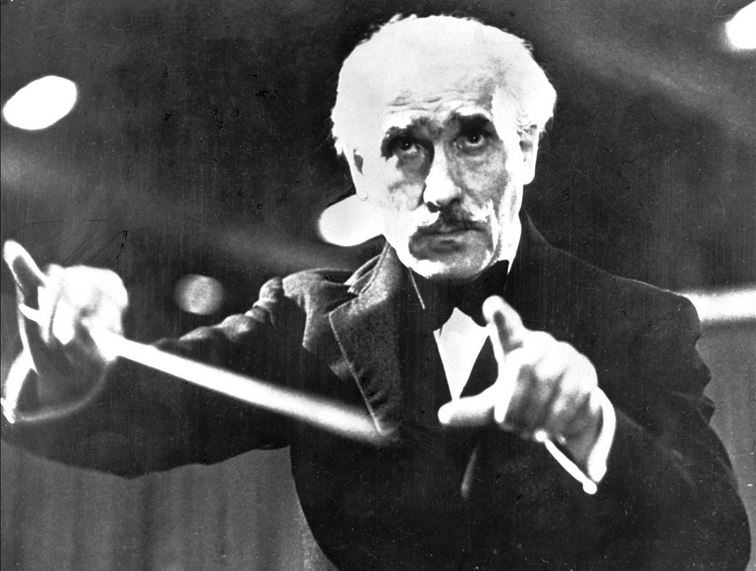

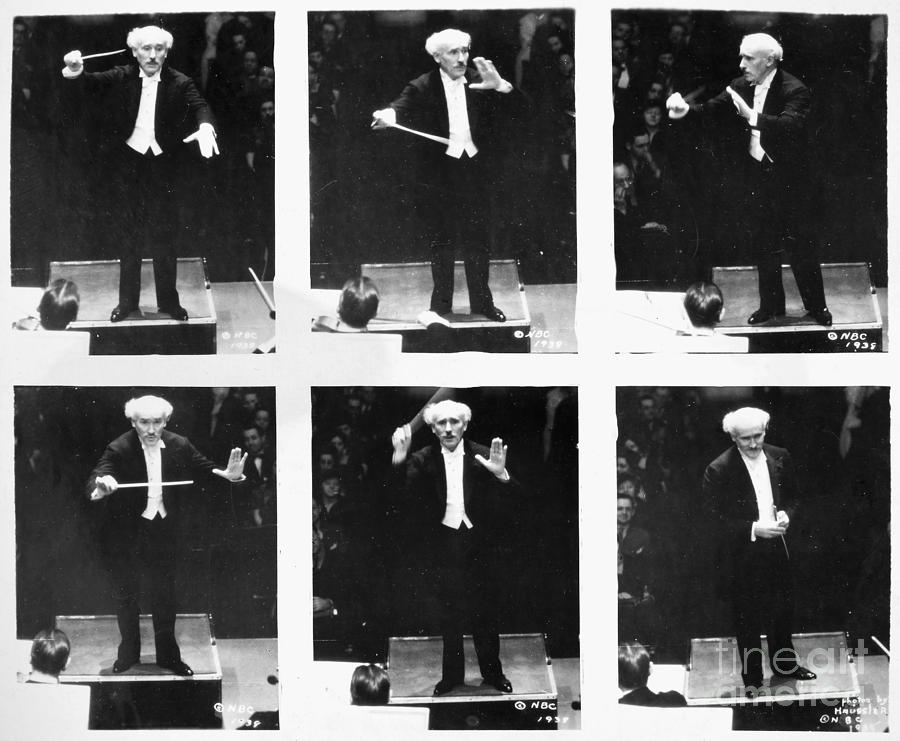

Arturo Toscanini was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed musicians of the late 19th and of the 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his photographic memory. He was at various times the music director of La Scala Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Later in his career he was appointed the first music director of the NBC Symphony Orchestra (1937–54), and this led to his becoming a household name (especially in the United States) through his radio and television broadcasts and many recordings of the operatic and symphonic repertoire.

Early years

Toscanini was born in Parma, Emilia-Romagna, and won a scholarship to the local music conservatory, where he studied the cello. Living conditions at the conservatory were harsh. For example, his diet consisted almost completely of fish. When he became successful he never ate anything that came from the sea. He joined the orchestra of an opera company, with which he toured South America in 1886. While presenting Aida in Rio de Janeiro on June 25, Leopoldo Miguez, the locally hired conductor, reached the summit of a two-month escalating conflict with the performers due to his rather poor command of the work, to the point that the singers went on strike and forced the company’s general manager to seek a substitute conductor. Carlo Superti and Aristide Venturi tried unsuccessfully to finish the work. In desperation, the singers suggested the name of their assistant Chorus Master, who knew the whole opera from memory. Although he had no conducting experience, Toscanini was eventually persuaded by the musicians to take up the baton at 9:15 pm, and led a performance of the two-and-a-half hour opera, completely from memory. The public was taken by surprise, at first by the youth and sheer aplomb of this unknown conductor, then by his solid mastery. The result was astounding acclaim. For the rest of that season Toscanini conducted eighteen operas, all with absolute success. Thus began his career as a conductor, at age 19.

Upon returning to Italy, Toscanini set out on a dual path for some time. He continued to conduct, his first appearance in Italy being at the Teatro Carignano in Turin, on November 4, 1886, in the world premiere of the revised version of Alfredo Catalani’s Edmea (it had had its premiere in its original form at La Scala, Milan, on February 27, of that year). This was the beginning of Toscanini’s lifelong friendship and championing of Catalani; he even named his first daughter Wally after the heroine of Catalani’s opera La Wally. However, he also returned to his chair in the cello section, and participated as cellist in the world premiere of Verdi’s Otello (La Scala, Milan, 1887) under the composer’s supervision. Verdi, who habitually complained that conductors never seemed interested in directing his scores the way he had written them, was impressed by reports from Arrigo Boito about Toscanini’s ability to interpret his scores. The composer was also impressed when Toscanini consulted him personally about Verdi’s Te Deum, suggesting an allargando where it was not set out in the score. Verdi said that he had left it out for fear that “certain interpreters would have exaggerated the marking”.

National and International Fame

Gradually, Toscanini’s reputation as an operatic conductor of unusual authority and skill supplanted his cello career. In the following decade, he consolidated his career in Italy, entrusted with the world premieres of Puccini’s La bohème and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. In 1896, Toscanini conducted his first symphonic concert (in Turin, with works by Schubert, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Wagner). He exhibited a considerable capacity for hard work, conducting 43 concerts in Turin in 1898. By 1898, Toscanini was Principal Conductor at La Scala, where he remained until 1908, returning as Music Director, from 1921–1929. He brought the La Scala Orchestra to the United States on a concert tour in 1920/21, during which he made his first recordings (for the Victor Talking Machine Company).

Outside Europe, Toscanini conducted at the Metropolitan Opera in New York (1908-1915) as well as the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1926-1936). He toured Europe with the New York Philharmonic in 1930. At each performance, he and the orchestra were acclaimed by critics and audiences.

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957), Lotte Lehmann (1888-1976) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

Toscanini was the first non-German conductor to appear at Bayreuth (1930-1931), and the New York Philharmonic was the first non-German orchestra to play there. In the 1930s, he conducted at the Salzburg Festival (1934–1937), as well as the 1936 inaugural concert of the Palestine Orchestra (later renamed the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) in Tel Aviv, later conducting them in Jerusalem, Haifa, Cairo and Alexandria.

During his engagement with the New York Philharmonic, Hans Lange, the son of the last Master of the Sultan’s Music in Istanbul, who, later, became conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the legendary founder of the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra as a professional ensemble, was his concert master. During his career, Toscanini collaborated with such legendary artists as Enrico Caruso, Feodor Chaliapin, Ezio Pinza, Jussi Björling, and Geraldine Farrar. Although he also worked with Wagnerian heldentenor Lauritz Melchior, he would not work with Melchior’s frequent partner Kirsten Flagstad after her political sympathies became suspect during World War II; it was Helen Traubel who sang with Melchior instead of Flagstad at the Toscanini concerts.

Lusitania

In May 1915, Toscanini was set to return to Europe aboard the doomed RMS Lusitania when his season at New York’s Metropolitan Opera ended. Instead, he cut his concert schedule short and left a week earlier, apparently aboard the Italian liner Duca degli Abruzzi.

Departure from Italy to the United States

In 1919, Toscanini ran unsuccessfully as a Fascist parliamentary candidate in Milan. He had been called “the greatest conductor in the world” by Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Toscanini became disillusioned with fascism already before the March on Rome and repeatedly defied the Italian dictator. He refused to display Mussolini’s photograph or conduct the Fascist anthem Giovinezza at La Scala. He raged to a friend, “If I were capable of killing a man, I would kill Mussolini.”

At a memorial concert for Italian composer Giuseppe Martucci on May 14, 1931 at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna, Toscanini was ordered to begin by playing Giovinezza, but he refused, despite the presence of fascist foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano in the audience. Afterwards, he was, in his own words, “attacked, injured and repeatedly hit in the face” by a group of blackshirts. Mussolini, incensed by the conductor’s refusal, had his phone tapped, placed him under constant surveillance, and confiscated his passport. The passport was returned only after a world outcry over Toscanini’s treatment. Upon the outbreak of WWII, Toscanini left Italy. He returned seven years later, to conduct a concert at the restored La Scala Opera House, which was destroyed during the war.

NBC Symphony Orchestra (NSO)

Toscanini returned to the United States where the NBC Symphony Orchestra was created for him in 1937. He conducted his first NBC broadcast concert on December 25, 1937, in NBC Studio 8-H in New York City’s Rockefeller Center. The acoustics of the specially built studio were very dry; some remodeling in 1939 added a bit more reverberation. (In 1950, 8-H was converted into a television studio. It has been home to NBC’s Saturday Night Live since 1975. In 1980, Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra began a series of special televised NBC concerts called “Live From Studio 8H”, the first one being a tribute to Toscanini, punctuated by clips from his television concerts.)

The NBC broadcasts were preserved on large transcription discs, recorded at both 78-rpm and 33-1/3 rpm, until NBC began using magnetic tape in 1947. NBC used special RCA high fidelity microphones both for the broadcasts and for recording them; these microphones can be seen in some photographs of Toscanini and the orchestra. Some of Toscanini’s recording sessions for RCA Victor were mastered on sound film in a process developed about 1941, as detailed by RCA producer Charles O’Connell in his memoirs, On and Off The Record. In addition, hundreds of hours of Toscanini’s rehearsals with the NBC were preserved and are now housed in the Toscanini Legacy archive at The New York Public Library.

Toscanini was often criticized for neglecting American music; however, on November 5, 1938, he conducted the world premieres of two orchestral works by Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings and Essay for Orchestra. The performance received significant critical acclaim. In 1945, he led the orchestra in recording sessions of the Grand Canyon Suite by Ferde Grofé in Carnegie Hall (supervised by Grofé) and An American in Paris by George Gershwin in NBC’s Studio 8-H. Both works had earlier been performed in broadcast concerts. He also conducted broadcast performances of Copland’s El Salón México; Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with soloists Earl Wild and Benny Goodman and Piano Concerto in F with pianist Oscar Levant; and music by other American composers, including marches of John Philip Sousa. He even wrote his own orchestral arrangement of The Star-Spangled Banner, which was incorporated into the NBC Symphony’s performances of Verdi’s Hymn of the Nations, together with the Soviet Internationale. (Earlier, while music director of the New York Philharmonic, he conducted music by Abram Chasins, Bernard Wagenaar, and Howard Hanson.)

In 1940 Toscanini took the orchestra on a “goodwill” tour of South America, sailing from New York on the ocean liner SS Brazil on 14 May. Later that year, Toscanini had a disagreement with NBC management over their use of his musicians in other NBC broadcasts. This, among other reasons, resulted in a letter which Toscanini wrote on March 10, 1941 to RCA’s David Sarnoff. He stated that he now wished “to withdraw from the militant scene of Art” and thus declined to sign a new contract for the up-coming winter season, but left the door open for an eventual return “if my state of mind, health and rest will be improved enough”. So Leopold Stokowski was engaged on a three-year contract instead and served as the NBC Symphony’s music director from 1941 until 1944. Toscanini’s state of mind soon underwent a change and he returned as Stokowski’s co-conductor for the latter’s second and third seasons resuming full control in 1944.

One of the more-remarkable broadcasts was in July 1942, when Toscanini conducted the American premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7. Because of World War II, the score was microfilmed in the Soviet Union and brought by courier to the United States. Stokowski had previously given the US premieres of Shostakovich’s 1st, 3rd and 6th Symphonies in Philadelphia, and in December 1941 urged NBC to obtain the score of the 7th as he wanted to conduct its premiere as well. But Toscanini coveted this for himself and there were a number of remarkable letters between the two conductors (reproduced by Harvey Sachs in his biography) before Stokowski agreed to let Toscanini have the privilege of conducting the first performance. Unfortunately for New York listeners, a major thunderstorm virtually obliterated the NBC radio signals there, but the performance was heard elsewhere and preserved on transcription discs. It was later issued by RCA Victor in the 1967 centennial boxed set tribute to Toscanini, which included a number of NBC broadcasts never released on discs. In Testimony Shostakovich himself expressed a dislike for the performance, after he heard a recording of the broadcast. In Toscanini’s later years the conductor expressed dislike for the work and amazement that he had actually conducted it.

In the spring of 1950, Toscanini led the orchestra on an extensive transcontinental tour. It was during that tour that the well-known photograph of Toscanini riding the ski lift at Sun Valley, Idaho was taken. Toscanini and the musicians traveled on a special train chartered by NBC.

The NBC concerts continued in Studio 8-H until 1950. They were then held in Carnegie Hall, where many of the orchestra’s recording sessions had been held, because of the dry acoustics of Studio 8-H. Toscanini’s final broadcast performance, an all-Wagner program, took place on April 4, 1954, in Carnegie Hall. That June, he participated in his final recording sessions, remaking portions of two Verdi operas so they could be commercially released. Toscanini was 87 years old when he retired. After his retirement, the NBC Symphony was reorganized as the Symphony of the Air, making regular performances and recordings, until it was disbanded in 1963. It was heard one last time (as the NBC Symphony Orchestra) in the 1963 telecast of Gian Carlo Menotti’s Christmas opera for television, Amahl and the Night Visitors.

Last years

With the help of his son Walter, Toscanini spent his remaining years evaluating and editing tapes and transcriptions of his performances with the NBC Symphony for possible future release. Many of these recordings were eventually issued by RCA Victor. Sachs and other biographers have documented the numerous conductors, singers, and musicians who visited Toscanini during his retirement. He was a big fan of early television, especially boxing and wrestling telecasts, as well as comedy programs.

Toscanini died on January 16, 1957 at the age of 89 at his home in the Riverdale section of the Bronx in New York City. His body was returned to Italy and was buried in the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan. His epitaph is taken from one account of his remarks concluding the 1926 premiere of Puccini’s unfinished Turandot: “Qui finisce l’opera, perché a questo punto il maestro è morto” (“Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died”). During his funeral service, Leyla Gencer sang an aria from Verdi’s Requiem. In his will, he left his baton to his protégée Herva Nelli, who sang in the broadcasts of Otello, Aïda, Falstaff, the Verdi Requiem, and Un ballo in maschera. Toscanini was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987.

Personal life

Toscanini married Carla De Martini on June 21, 1897, when she was not yet 20 years old. Their first child, Walter, was born on March 19, 1898. A daughter, Wally, was born on January 16, 1900. Carla gave birth to another boy, Giorgio, in September 1901, but he died of diphtheria on June 10, 1906. Then, that same year (1906), Carla gave birth to their second daughter, Wanda.

Toscanini worked with many great singers and musicians throughout his career, but few impressed him as much as Vladimir Horowitz. They worked together a number of times and recorded Brahms’ second piano concerto and Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto with the NBC Symphony for RCA Victor. Horowitz also became close to Toscanini and his family. In 1933, Wanda Toscanini married Horowitz, with the conductor’s blessings and warnings. It was Wanda’s daughter, Sonia, who was once photographed by Life playing with the conductor. During World War II, Toscanini lived in Wave Hill, a historic home in Riverdale. Despite the reported infidelities revealed in Toscanini’s letters documented by Harvey Sachs, he remained married to Carla until she died on June 23, 1951.