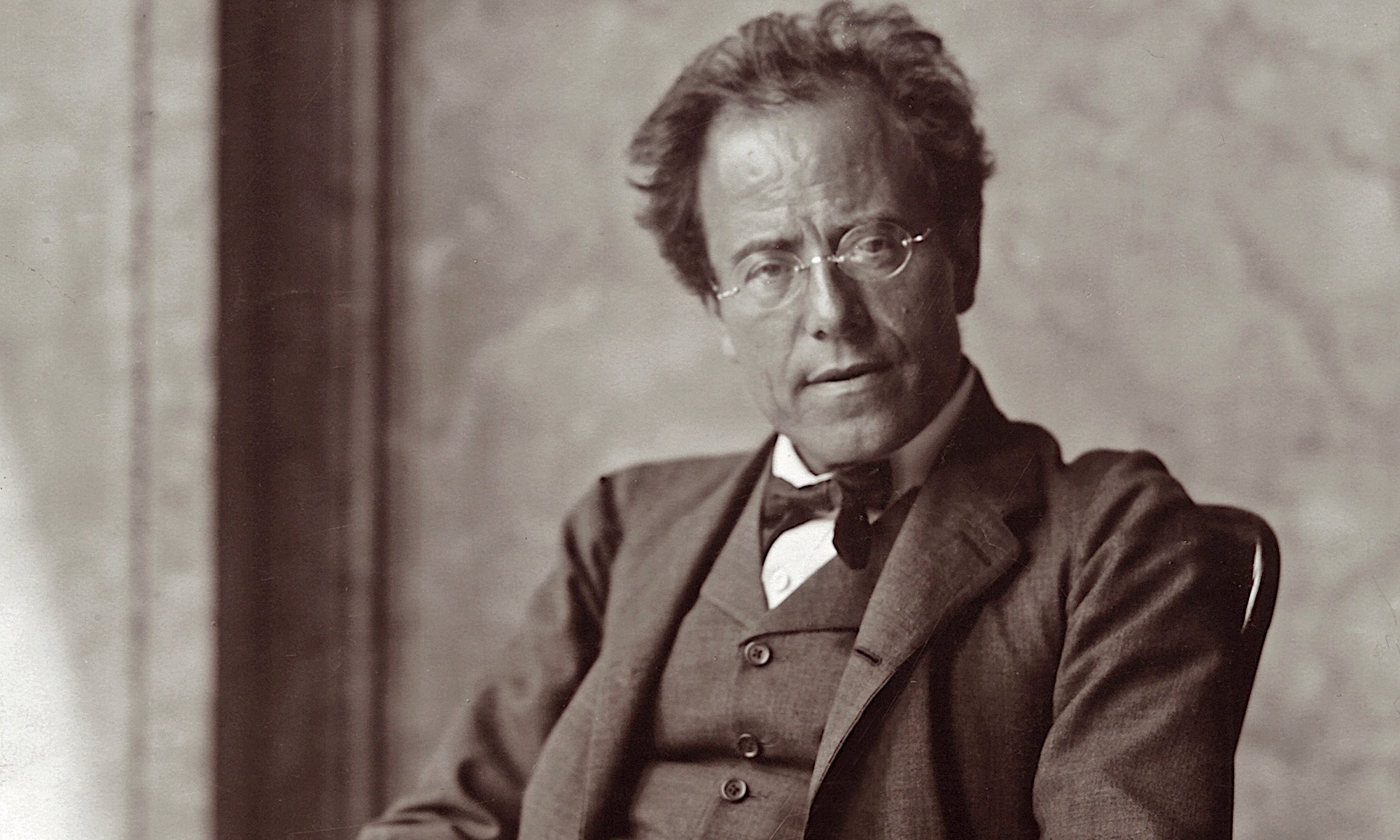

Rückert-Lieder is a song cycle of five Lieder for voice and orchestra or piano by Gustav Mahler, based on poems written by Friedrich Ruckert (1788-1866).

- Lied Ruckert 1: Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder

- Lied Ruckert 2: Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!

- Lied Ruckert 3: Um Mitternacht

- Lied Ruckert 4: Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen

- Lied Ruckert 5: Liebst du um Schoenheit

Friedrich Ruckert (1788-1866), an editor and professor of Oriental languages, wrote poetry in imitation of Asian and Middle Eastern styles, in addition to the beautiful examples of German lyric romantic poems which Mahler collected for this set of songs.

Much of Mahler’s music is driven by melody, and he sometimes became so attached to the melodies of his songs and the messages which they conveyed that he appropriated many of them for use in his symphonies. One of Mahler’s special gifts was his ability to convey complex emotions with seemingly simple melodic lines. A good example of this can be found in the song Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft! where the opening line, “I breathed a gentle fragrance!” is brought to life with Mahler’s luxuriant melodic setting, and we can almost smell the gentle fragrance drifting by.

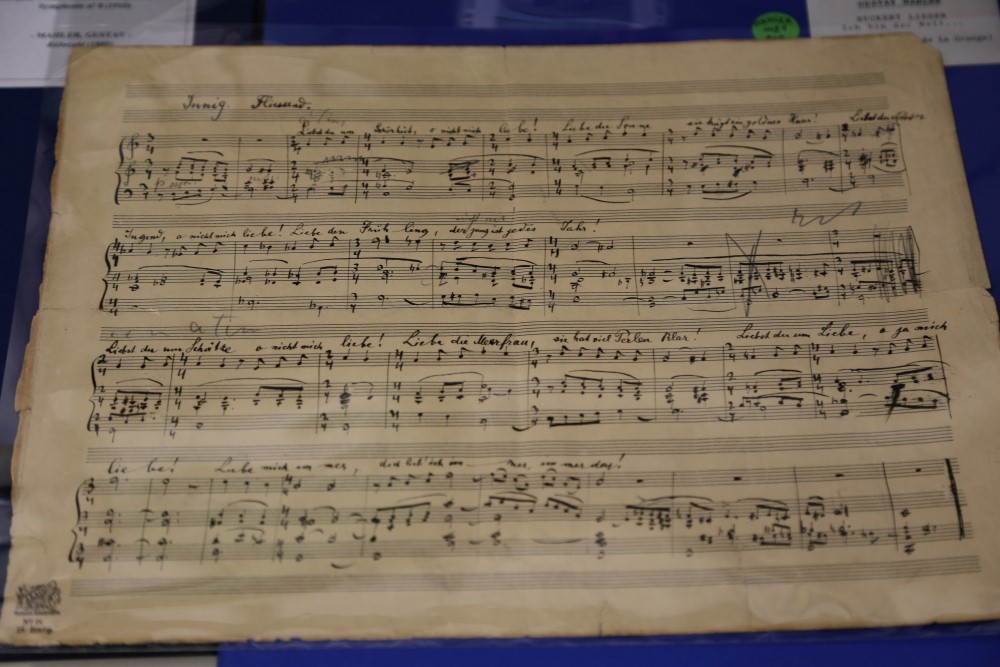

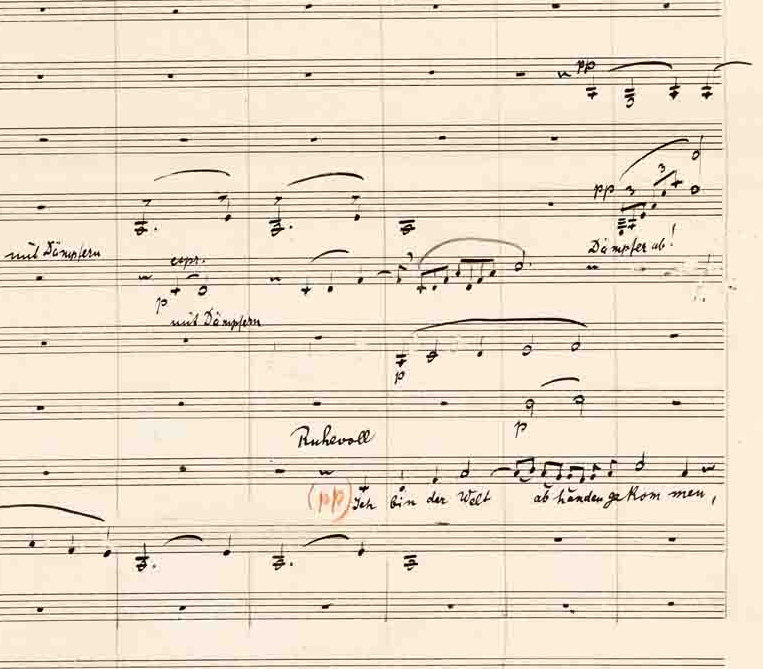

When one reads through the texts of Mahler’s Rückert Lieder, it is not difficult to see why they were so attractive to the hyper-romantic composer. Liebst du um Schönheit (“If you love for beauty”) was a present from Mahler to his wife Alma. This song is in the voice of a poor artist who has very little money or physical attractiveness, a predicament which Mahler related to himself. Of the third song, Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen (“I am lost to the world”), Mahler once said, “It is truly me.” In this poem, Rückert exquisitely captures the ethos of the romantic artist – a solitary figure, withdrawn from the world and all of its earthly distractions, destined to be alone and forgotten. The poetry’s tone of peaceful resignation is captured and amplified in the music, and indeed Mahler was a master at composing music in this vein.

The largest song in the set, Um Mitternacht (“At midnight”), takes us on a far-reaching journey of the soul. Mahler exploits the poem’s symmetrical construction, using repetition of phrases and patterns to draw us deeper and deeper into the night. By the end of the song Mahler leads us into a Wagner-like music drama, grounding us in the reality of time, yet transcending human and earthly spiritual boundaries.

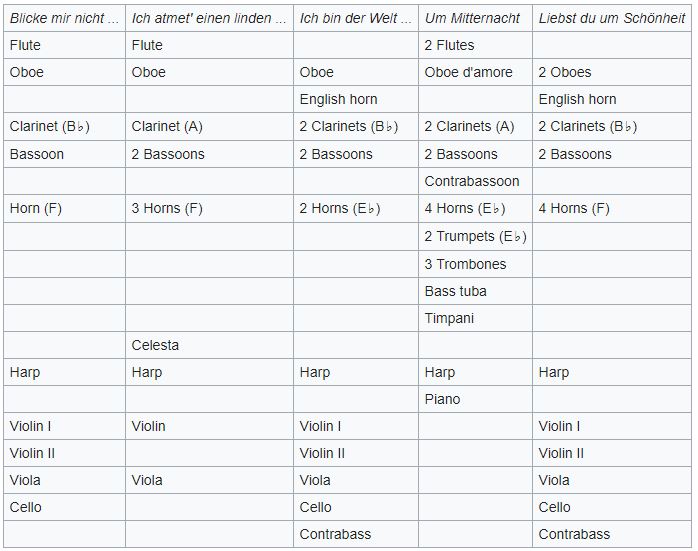

There is no hint in the Rückert-Lieder of Mahler as purveyor of orchestral gigantism. Except for the brooding, starkly scored ‘Um Mitternacht’ (wind and brass, without strings), these are his most lyrical songs. Mahler matches their subjective intimacy with orchestration of vocal eloquence, at once intricate and exquisitely delicate: in the gossamer textures (no cellos or basses) of ‘Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!’ (‘I breathed a gentle fragrance!’) that prefigure the ravishing chinoiserie of Das Lied von der Erde; or the veiled, plangent contrapuntal weave of cor anglais, clarinets, horns and muted strings in ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (‘I have lost touch with the world’), on the familiar Romantic theme of withdrawal into a secluded world of love, art and nature.

For economic reasons, concert-goers hear the Rückert-Lieder far more often with piano than with orchestra. Yet like the Wunderhorn songs and the Kindertotenlieder, their conception is essentially orchestral. Once experienced, it is hard to forgo the keening cor anglais in ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’, the mournful clarinets, oboe d’amore and nocturnal horns – and the final symphonic blaze – of ‘Um Mitternacht’, or the con sordino murmurings of ‘Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!’. However sympathetic the performers, the piano versions tend to stand in relation to the orchestral as a pen-and-ink sketch does to a painting.

Although Mahler’s two chosen soloists at the pioneering 1905 Lieder-Abend mit Orchester were baritones, most recordings feature mezzo-sopranos, the voice type we now think of as quintessentially Mahlerian. The published edition opens with the scherzo of the set, ‘Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder’ (‘Do not look into my songs’ – Mahler hated anyone prying into his unfinished works), followed by ‘Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft!’. Then come the longest, most profound songs, ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ and ‘Um Mitternacht’, with ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’ as a radiant envoi. This ordering can work in performance, though many singers prefer to end with the two ‘big’ songs, or to separate them with ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’.

Whatever their chosen order, any singer tackling the Rückert-Lieder must be attuned to their tenderness and intimacy, while conductors need an acute feeling for instrumental balance and pacing, not least in ‘Um Mitternacht’, with its many shifts of metre and tempo.

In their orchestral guise, four of the Rückert-Lieder were premiered at a sold-out concert in Vienna (1905 Concert Vienna 29-01-1905 – Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Kindertotenlieder, Ruckert-Lieder (Premieres)) that many Lieder lovers might be tempted to nominate as the greatest ever showcase of new songs: a ‘Lieder recital with orchestra’ – itself a revolutionary concept – in January 1905 that also included the premieres of the Kindertotenlieder and settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Crucially, Mahler chose the small Brahms-Saal of the Musikverein so that the songs could be performed ‘in the manner of chamber music’, in an apt acoustic.

Listening Guide