- Profession: Painter, graphic. Secession (member).

- Residences: Prague, Vienna, Berlin.

- Relation to Mahler: See Paintings, drawings and silhouettes.

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 21-07-1870 Prague, Czech Republic.

- Died: 28-09-1932 Berlin, Germany.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 New Jewish Cemetery (Jewish Cemetery of Prague-Zizkov), Zizkov Hrbitov, Prague, Czech Republic. Vinohradska 1835, Praha 3, Prague, Okres Praha, Prague Capital City, 130 00 Czech Republic

- See: Paintings, drawings and silhouettes.

Emil Orlik was a painter, etcher and lithographer. He was born in Prague, which was at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and lived and worked in Prague, Austria and Germany. Emil Orlik was the son of a tailor. He first studied art at the private art school of Heinrich Knirr, where one of his fellow pupils was Paul Klee.

From 1891, he studied at the Munich Academy under Wilhelm Lindenschmit. Later he learned engraving from Johann Leonhard Raab and proceeded to experiment with various printmaking processes.

After performing his military service in Prague, he returned to Munich, where he worked for the magazine Jugend. He spent most of 1898, travelling through Europe, visiting the Netherlands, Great Britain, Belgium, and Paris. During this time he became aware of Japanese art, and the impact it was having in Europe, and decided to visit Japan to learn woodcut techniques. He left for Asia in March 1900, stopping off in Hong Kong, before reaching Japan, where he stayed until February 1901.

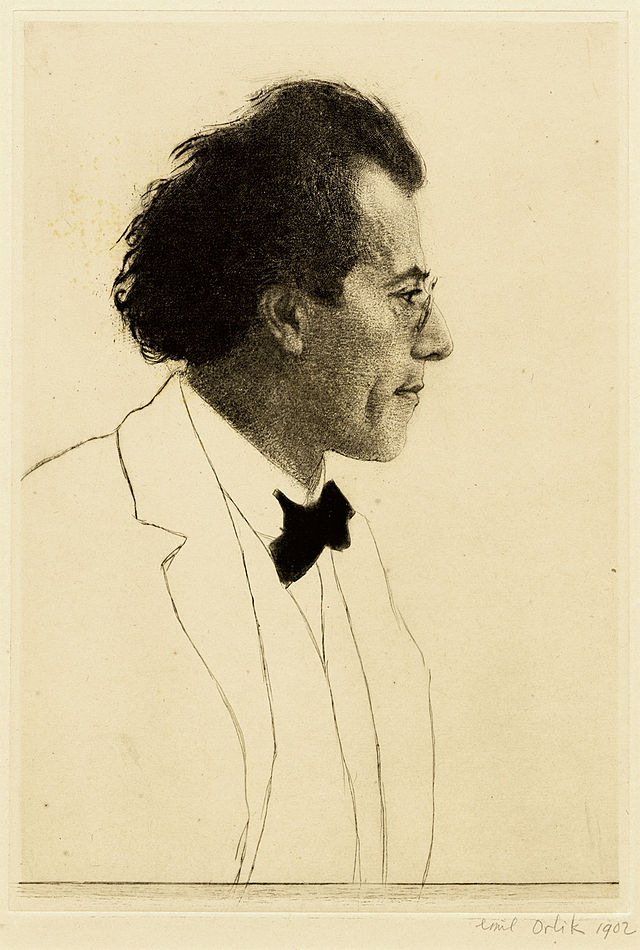

Year 1902. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) by Gustav Mahler by Emil Orlik (1870-1932)

1901. Japanese pilgrims on their way to Fujiyama by Emil Orlik (1870-1932).

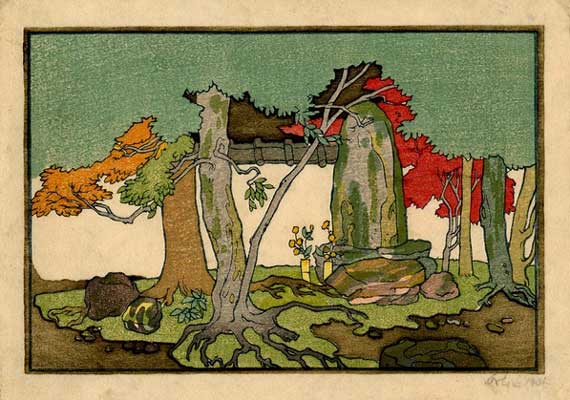

Temple Garden in Kyoto by Emil Orlik (1870-1932).

In 1905 Emil Orlik moved to Berlin and took a post at the “School for Graphic and Book Art” of the Museum of Decorative Arts (Kunstgewerbemuseum), now part of the Berlin State Museums. He taught at the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts, where one of his students was George Grosz.

More

Emil Orlik was born Prague on 21-07-1870. At that time Prague was the capital of a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and thus he was an Austrian citizen, not Czechoslovakian as is frequently stated. His family, being Jewish, lived near the Prague ghetto. His father was a master tailor as was his brother Hugo. There was a large German speaking community in Prague (called Bohemian Germans) including an artistic circle which included friends of Orlik’s such as Franz Kafka, Franz Werfel (1890-1945), Max Brod and Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926).

Throughout his school years Orlik had been passionate about drawing and on leaving school in 1889 he was allowed by his father to go to Germany, hoping to be enrolled at the Academy of Fine Art there. He was not accepted however, so he enrolled at the private art school of Heinrich Knirr in Munich, where a fellow pupil was Paul Klee. Orlik’s target remained the Munich Academy and he gained a place in 1891 under Professor von Lindenschmit who soon recognised his talents and allocated him a small studio.

Orlik worked hard, copying old masters at the Munich Pinakothek, constantly improving his techniques. In 1893 he won the silver medal for two of his pastel drawings which were shown at the academy’s annual exhibition, with the honour of hanging near works by Adolph von Menzel, one of the most prominent artists in Germany. The Academy had a department led by Professor Raab teaching copper engraving. Orlik enrolled for these classes but was at loggerheads with the professor for branching away from the curriculum, experimenting with all aspects of etching and lithography. He was soon doing work beyond Raab’s understanding.

In 1893 Orlik impetuously left the academy as he felt constrained by conservative academic training. He wanted to start working in more modern styles and was drawn to the Munich Naturalistic movement and the circle around Wilhelm Leibl. After a year of military training he returned to Prague in 1894 and painted and made prints of his friends and surroundings there.

In 1896 Orlik returned to Munich to work with his fellow pupil and life-long friend Bernhard Pankok on their first essays in the making of colour woodcut prints. They had seen examples of Japanese woodcut prints and were fascinated by them. He began contributing illustrations to the journal Jugend. By 1897 Orlik was such an accomplished print-maker that four of his small etchings were chosen for publication in the prestigious art magazine PAN. Also illustrated in PAN was a reproduction of his first poster ‘Die Weber’, designed for the play of the same name produced by Gerhart Hauptmann (1868-1946).

Hauptmann was so impressed by the poster that he invited Orlik to Berlin to visit his studio and this was the first stepping stone to Orlik’s involvement in the theatre. He went on to become a leading set and costume designer for many productions. Through his friend the writer Maria Rainer Rilke came the opportunity to become a book illustrator. By the end of 1897 Max Lehrs, assistant director of the Kupferstichkabinett (Graphics Collection) in Dresden began to add prints by Orlik to this important museum print collection. Lehrs can be considered to be the ‘discoverer’ of Orlik and he bought may of Orlik’s prints for his own extensive collection.

They were lifetime friends and maintained a correspondence almost until the artist’s death. Much of the details of Orlik’s travels and day-to-day life is known from this correspondence, which has amazingly been preserved. A book titled Malergr?sse (Artists Greetings) was published by Prestel in 1981 illustrating and transcribing the profusely illustrated letters and postcards.

In 1898 Orlik made his first journey abroad, visiting England, Scotland, Belgium and Holland as well as making the first of his many visits to Paris. There he came into contact with the woodcut artist Felix Vallotton and in London with William Nicholson who was making highly innovative woodcut posters and prints. He recorded his travels in numerous etchings, lithographs and woodcuts.

On returning to Prague he established himself in an atelier in an old tower with fine views over the picturesque city. He retained this studio until 1904. But by 1899 he was living in Vienna and showed works in the third exhibition of the Vienna Secession, of which, as a member, he also contributed to the group’s publications on modern art trends, including ‘Japonisme’. The Society was gaining in importance and visitors came from abroad, including K?the Kollwitz and Max Liebermann from Germany, and Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Camille Pissarro from Paris.

There was much interchanging of ideas and discussion of Japonisme which was having such an impact throughout Europe, particularly on Art Nouveau and Jugendstil artists, and the Nabis school in Paris. At the same time artists in America were also coming under this influence (notably Mary Cassatt and Helen Hyde).

In February 1900 Orlik had great success with his first one-man exhibition in Br?nn in Austria, showing works in many media. It was at this time that Max Lehr introduced Orlik to Marie von Gomperz and her family. Her father, Max von Gomperz was a wealthy industrialist and patron of the arts. He bought from and commissioned many paintings and other works by Orlik. Marie Gomperz and Orlik developed a life-long friendship documented through their correspondence which continued until the time of Orlik’s death. The extensive Gomperz collection of his work was exhibited at the Jewish Museum in Vienna in 1997.

Orlik’s oeuvre reflects this patronage and friendship through many portraits of members of the family and of their country estate of Oslawan in Slovakia and its surroundings.

Meanwhile, in March of 1900 Orlik undertook his first voyage to the Far East, the momentous ‘Reise nach Japan’. He wanted to learn at first hand and at its source how to master the techniques which were of such fascination to him. He absorbed much knowledge from the artists, woodblock-carvers and printers with whom he worked. He wrote many letters with descriptions of his travels in Japan to friends in Europe and Reiner Maria Rilke contributed an article to the magazine ‘Ver Sacrum’ relating the descriptions written to him by Orlik. He wrote to Max Lehr on 22-02-1901 that he had spent a fortune on acquiring prints, netsuke and other Japanese artefacts.

As soon as Orlik arrived home in November 1901 he had to prepare for an important exhibition of his work to be held at the prestigious Cassirer Gallery in Berlin in December. During the following year Orlik had a series of one-man shows in many venues, including one at the Rudolfinum in Prague at which the entire exhibition was bought by the Prague Kupferstichabinett.. At the XIIIth exhibition of the Vienna Secession he showed 16 works, all of Japanese subjects, alongside works by Max Klinger.

His name now appeared in the index of the Berlin Secession, together with those of Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Monet and Camille Pissarro. Many articles appeared in various publications about his Japanese travels, the artefacts he brought back and his work. He travelled again to England and Paris, where the work of Cezanne made a great impression on him.

At the end of 1904 Orlik was appointed head of the department for graphic art and book illustration at the Academy of the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin, the teaching post he retained until his retirement in 1930. Among his many pupils who gained fame in their own right was George Grosz who wrote admiringly of Orlik’s teaching in his autobiography.

Orlik was now established in Berlin and began working on his costume and stage designs for the Deutsches Theater, led by Max Reinhardt. Many more articles about him and his work appeared in various publications, including one in ‘The Studio’ in London. At this time Orlik met and became friendly with the Berlin Secession group led by Max Liebermann, who had just returned from Paris and was to become the leading German Impressionist painter. Other important members of the group were Lovis Corinth, Erich Buttner and Max Slevogt. The SPOG group was also founded Slevogt, Pankok, Orlik and Grundberg. Grunberg was a dentist but also a fine amateur artist.

Orlik had met the author Lafcadio Hearn in Japan. Hearn had assumed Japanese citizenship under a Japanese name and he lectured at a number of universities writing many books on the country and its culture which were widely read in England and America and greatly furthered knowledge in Europe of Japanese life, philosophy and art. Orlik both translated Hearn’s books into German and illustrated them.

Over the next few years Orlik was indefatigable in holding exhibitions in many venues and in working in theatre design. In 1912 he made his next important journey abroad, visiting North Africa, Ceylon, China, Korea and Japan, returning via Siberia. In Egypt he executed an outstanding series of etchings later published in a portfolio Aus Aegypten.

Returning to Germany he continued to play a leading role in the Berlin Secession until 1913 when he and Liebermann both resigned. Book design became an important part of Orlik’s oeuvre, as well as ex libris labels for literally hundreds of friends and book collectors. Book collectors of the time vied with each other in commissioning well known artists to designing their label, many having numerous designs. In all, Orlik designed 136 ex libris and although about a dozen were made gratis for close friends, the work was lucrative. He was paid up to 500 marks each, a considerable sum in pre-World War I days.

Orlik was also called upon to design colour posters for exhibitions, theatre productions and even commercial products. He produced hundreds of posters most of which are today highly sought after and scarce.

In December 1917 Orlik was appointed official artist to the Best-Litovsk Peace Conference at which Russia and Germany ended their conflict. He produced 72 portrait studies at the conference, including a number of Leo Trotsky. Many of these he later published as lithographs in a portfolio.

1919. Portrait by Emil Orlik (1870-1932) of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) for Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951). 24-04-1920. Gustav Mahler Festival Amsterdam 1920. Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951). Gedenkboek. Commemorative book. 1895-1920. Trade edition. Publisher Martinus Nijhoff (1920), The Hague.

After the war he continued working at a frantic pace, exhibiting at many venues throughout Europe. He also became interested in photography, experimenting with the use of light. He was one of the pioneers in the use of photographs as studies for graphics and paintings, particularly for his portraits of leading celebrities. He claimed that photography permitted him to obtain the essence of his endeavours towards the perfect portrait. His earliest essays in photography were made around 1917, but by the mid-twenties he produced brilliant photo portraits of Marlene Dietrich, Albert Einstein and many others.

In December 1923 Orlik made his last voyage out of Europe. He received a commission to paint the portrait of a sitter in Cincinnati. His passage and a two month’s stay in the USA were provided. While in America he had an exhibition in New York. The City fascinated him and he wrote to Gerhart Hauptmann (1868-1946): “After overcoming the first confusion it is a completely different world. The city is amazing. The dollar rules here!”. He said he found it easier to get used to China than to New York.

After his return to Europe he continued to work intensely and his fame increased. He became one of the best known artists of the day. He continued travelling in Europe – to Spain, Italy, England and France. Portrait commissions and graphic work kept him busy till the time of his death from a heart attack in Berlin on 28-09-1932, nine days after his great friend Max Slevogt.

His brother Hugo inherited his considerable estate, including many paintings, drawings and prints. During his many visits to Paris he had acquired a fine collection of works by his friend Henri Matisse and by many other prominent artists, including Cezanne. Hugo Orlik and his family perished during the war at the hands of the Nazis. The only survivor of the family was an aunt who, after the war, regained some of what was left of Emil’s effects.