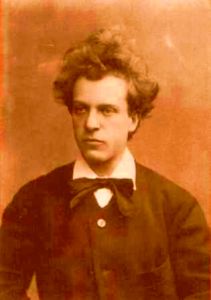

- Profession: Composer.

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler: Friend, classmate University of Vienna (where they shared a room).

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 01-08-1858 Braunhirschengrund, Vienna, Austria.

- Declared crazy: 22-10-1880.

- Died: 25-06-1884 Provincial Lunatic Asylum of Lower Austria, Brunnlfeld, Vienna, Austria. Aged 25.

- Buried: 28-06-1884 Central cemetery, Vienna. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) attended funeral. On 31-03-2004 the Internationale Hans Rott Gesellschaft put up a commemorative plaque at the hitherto anonymous burial place. Location plaque is 23-2-59.

Hans Rott was an Austrian composer and organist. His music is little-known today, though he received high praise in his time from Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner. Rott was born in Braunhirschengrund, a suburb of Vienna. His mother Maria Rosalia (1840-1872, maiden name Lutz) was an actress and singer. His father Carl Mathias Rott (real name Roth, born 1807, married 1862) was a famous comic actor in Vienna who was crippled in 1874 by a stage accident which led to his death two years later.

Hans was left alone to continue his studies at the Conservatory. Fortunately, both his skill and financial need were recognized and he was excused from paying tuition. While studying, he briefly roomed with Gustav Mahler and Rudolf Krzyzanowsky. He studied piano with Leopold Landskron and Josef Dachs, harmony with Hermann Graedener, counterpoint and composition – like Mahler – with Franz Krenn. He studied organ with Bruckner, starting in 1874, and graduating from Bruckner’s organ class in 1877, with honors. Bruckner said that Rott played Bach very well, and even improvised wonderfully (a high compliment since Bruckner himself was a great improviser). Rott was also influenced by the works of Wagner, and even attended the very first Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

During that time Rott was also organist at the Piarist church “Maria Treu” in Vienna. For the final year of his studies in 1878, Rott submitted the first movement of his Symphony in E major to a composition contest. The jury, except Bruckner, was very derisive of the work. After completing the Symphony in 1880, Rott showed the work to both Brahms and Hans Richter, in order to get it played. His efforts failed. Brahms did not like the fact that Bruckner exerted great influence on the Conservatory students, and even told Rott that he had no talent whatsoever and that he should give up music. Unfortunately, Rott lacked Mahler’s inner resolve, and whereas Mahler was able to overcome many of the obstacles in his life, Rott was brought down by mental illness. Hans Rott also wrote a Symphony for String Orchestra in A flat major, in three movements, (1874-1875), and a String Quartet in C minor, a student work in five movements.

Final years

Rott’s mind snapped in October 1880, whilst on a train journey. He was reported to have threatened another passenger with a revolver, claiming that Brahms had filled the train with dynamite. Rott was committed to a mental hospital in 1881, where despite a brief recovery, he sank into depression. By the end of 1883 a diagnosis recorded ‘hallucinatory insanity, persecution mania—recovery no longer to be expected.’ He died of tuberculosis in 1884, aged only 25. Many well-wishers, including Bruckner and Mahler, attended Rott’s funeral at the Central cemetery in Vienna.

Gustav Mahler wrote of Rott:

a musician of genius … who died unrecognized and in want on the very threshold of his career. … What music has lost in him cannot be estimated. Such is the height to which his genius soars in … [his] Symphony [in E major], which he wrote as 20-year-old youth and makes him … the Founder of the New Symphony as I see it. To be sure, what he wanted is not quite what he achieved. … But I know where he aims. Indeed, he is so near to my inmost self that he and I seem to me like two fruits from the same tree which the same soil has produced and the same air nourished. He could have meant infinitely much to me and perhaps the two of us would have well-nigh exhausted the content of new time which was breaking out for music.

Thanks to Rott’s friends, some of his music manuscripts have survived in the music collection of Vienna’s national library. This includes Rott’s Symphony in E major, and sketches for a second Symphony that was never finished. The completed symphony is remarkable in the way it anticipates some of Mahler’s musical characteristics. In particular the third movement is unnervingly close to Mahler. The Finale includes references to Brahms’s First Symphony. Mahler also spoke well of Rott’s Lieder, of which all eight surviving complete songs have been performed in concert since 2002 and four sung by Dominik Wörner were recorded in 2009 on the Ars label. We also know of a Sextet, which Mahler never heard and has also been lost. In his last years, Rott wrote a lot of music, only to destroy what he wrote soon after writing it, saying it was worthless.

Bruckner and Mahler were the first to recognise Rott’s talent. Mahler himself included references to Rott’s work in his own music. However, in the 20th century, Rott’s work was largely forgotten; and only in 1989 was Rott’s Symphony in E major finally premiered by the Cincinnati Philharmonia Orchestra under Gerhard Samuel, in a performing edition prepared by Paul Banks. A CD recording followed. Other recordings of the symphony have since been issued, and other Rott works have been occasionally revived, including his Julius Caesar Overture, Pastoral Overture and Prelude for Orchestra.

More on Hans Rott

Hans Rott was born on August 1, 1858 in Braunhirschengrund, a suburban parish of Vienna (today Vienna XV) as illegitimate son of the actor Carl Mathias Rott (real name Roth) and the singer and actress Maria Rosalia Lutz. After his parents had married his father legitimized him in 1863.

From 1874 to 1878 he studied at the Conservatoire for Music and Performing Arts of the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna: piano with Leopold Landskron, organ with Anton Bruckner, harmony with Hermann Grädener and composition with Franz Krenn (together with Gustav Mahler and others).

1876 Rott, a member of the Viennese Academic Wagner Society, attended the first Bayreuth Festival. From 1876 to 1878 he was employed as organist at the Piaristen Church (Maria Treu) in Vienna with lodgings in the Piaristen Monastery. His rooms became the meeting point for numerous fellow students and friends, among them the musicians Rudolf Krzyzanowski, Gustav Mahler, Hugo Wolf, the philologist and archaeologist Friedrich Löwy (as from 1887 Löhr) as well as the scholar of German philology Joseph Seemüller.

Still during his musical studies Rott became an orphan in 1876. Anton Bruckner tried in vain to find a post as organist in St Florian resp. Klosterneuburg for his “favourite student”. From 1878 on Rott made a living by giving private music lessons and he received financial support from his friends.

When in September 1880 he presented his First Symphony to Johannes Brahms, a member of the jury deciding on the grant of a state scholarship Rott had applied for, he met with a harsh rebuff by Bruckner’s antipode. And yet another of his hopes was doomed: Court Opera Conductor Hans Richter, although showing an interest in a performance of the symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, was reluctant to commit himself.

In October 1880 chain of unfortunate accidents exerting a heavy psychic strain on Rott caused an already lurking insanity to break out. During a train ride to Mulhouse in the Alsace where he had accepted a position as music director and choir master he pointed a pistol at a fellow traveller to prevent him from lighting a cigar. The reason for his conduct he gave was that Brahms had had the carriage filled with dynamite.

In February 1881 Rott was transferred from the Psychiatric Hospital of the General Hospital in Vienna to the Provincial Lunatic Asylum of Lower Austria. The diagnosis was: insanity, hallucinatory persecution mania. He continued composing at the asylum, later on, however, he gradually developed a deep depression and destroyed some of his compositions. Following several attempts of suicide he finally died of tuberculosis on June 25, 1884 not yet 26 years old.

More on Hans Rott

Hans Rott (1858-1884): The Missing Link Between Bruckner and Mahler by Tess James

The relationship between Gustav Mahler and his friend/significant influence Hans Rott is discussed in this essay, as well as the relationship of Bruckner and his favourite student Rott. The essay contains a brief treatment of Rott’s major work, the symphony in E Major and discusses how the history of music would have changed, had he lived longer.

What music has lost in him is unmeasurable. His first symphony soars to the heights of such genius as to make him the founder of the new symphony as I know it. (Mahler on Rott)

You will not find a finer young man or a better musician (Bruckner on Rott)

Every once in a while, a name is resurrected from the forgotten shrouds of musical history which has remained there unjustly, giving rise to an exciting new field of research. One of these is Viennese-born composer Hans Rott, who lived from 1858–1884. He was a favourite student of Bruckner as well as one of the major influences on his friend and contemporary Gustav Mahler.

This past summer, I was in Vienna, together with Bob Freeman and Patricia Hall, both from the music department of UCSB. We found ourselves sitting in a little café, somewhere behind the Spanish riding school. Bob expertly ordered the most delightful pastries from the menu as he informed me that I was in shock, and needed something to get me on my feet again, preferably something with plenty of cream on top. “That always helps” he insisted as the waiter placed the first creamy-spongy cake-thing before me.

What had happened to bring us to this point? We had all run into each other at the Musiksammlung (Music collection) of the Oesterreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library). Bob had been in Austria for several weeks, on sabbatical, researching at the nearby Melk abbey and here in Vienna. Patricia, lucky woman, was off to Basel the next day. I had barely arrived to research the life of Mahler’s contemporary, and Bruckner favourite student, Hans Rott. That day, I had just survived my first encounter with the typical Viennese “Beamte”, who ran the Musiksammlung that day, in the absence of its kind director, Inge.

Inge was a beautiful, former opera singer whom we all loved. The “Beamte” were a completely different story. For anyone who ever wants to do research in Vienna, a little hint: Beamte are civil servants, but they don’t serve. They are unkuendbar (cannot be fired) and they have all the power. A special breed among them also pride themselves on being rude. The more friendly you are to them, the ruder they become.

That day, I had tracked clear across Vienna in the summer’s heat, and got lost a few times before making it to the Musiksammlung. Once there, exhausted and dehydrated, I had asked for a glass of water. This had been greeted by a “Beamte” with a tirade of abuse as she shuffled off to get me a glass of water. “Is she always that friendly?” I had asked another Beamte, who, completely straight faced and meaning it, said “yes”. By this time, the first Beamte had returned, thrust the glass into my hand together with another tirade of verbal abuse, and I was reduced to a nervous wreck, until Bob found me, and dragged me to the café.

Freeman advised me not to smile when I wanted something next time, but to be very assertive, and very straight-faced. “Ts Ts Ts” Freeman said, “you don’t realise it, but you are in shock. You are not used to being treated like this”.

As I ate my cake and drank a cup of strong, Viennese coffee to steel myself for going back into the Musiksammlung. I wished for nothing more than to change history—anything to mean that the papers I needed were not at the Musiksammlung. But the nature of the research made it worth the while, although it had been a “Rotten” day.

Hans Rott was born in Vienna on August 1st 1858, the son of a famous stage actor and Franz von Suppe contemporary, Karl Mathias Rott. Music ran in the family; Rott Sr. and von Suppe appeared together at the Theater an der Wien. By the time Hans Rott died in an insane asylum in 1884, he had left behind piles of scores of music, none of which had ever been performed or published.

This in itself would have only marked him as another forgotten could-have-been, had it not been for the quality of the music. In 1900, Rott’s friend Gustav Mahler borrowed the score of Rott’s 1st symphony, and was extremely impressed. He discussed it with Natalie Bauer-Lechner in the same year. “It is completely impossible to estimate what music has lost in him. His first symphony soars to the heights of such genius as to make him the founder of the new symphony as I understand it” (Bauer-Lechner, 1923).

It is clear that Mahler subsequently “enshrined the memory of his friend in his own music” (Banks 1989) or, as one critic put it upon hearing Rott’s first symphony in E Major (1878) “Mahler, you have blown your cover.”

The music and life of Hans Rott hence deserves closer examination on several counts: its own merit, its influence on Mahler, and Bruckner’s influence on Rott. Although Rott was in effect not discovered until 1989, and his music and biographical studies are still young, Rott has already found some important champions for his work.

The famous Vienna based American conductor Dennis Russel Davies, who performed Rott’s E-major symphony last year in September in Vienna, could hardly contain his enthusiasm. “A brilliant work” he said in a telephone conversation from Portugal. “I was very impressed.” So impressed that next year he will head the premiere a Rott piece, the orchestral work “Pastorales Vorspiel.” Russel Davies first heard of Rott through his German manager, Stuttgart based Dr. Schroeder. “I listened to the symphony and loved it,” Schroeder recalls. “So I put it to Dennis. He was at once impressed enough to perform it with the Vienna Radio Symphony orchestra at the Berlin Festival.”

Rott researchers like myself have already been approached by the program directors of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra with a view of performing the Rott symphony there in the year 2000 under the direction of James Levine.

This past year marked another important incident for Rott. In September 1998, Paul Banks and I both travelled from England to Vienna for the touching world premiere of Rott’s string quartet during the “Berliner Festspiele.” The premiere was undertaken by the Rosamunde Quartet, which is highly successful across Europe, under the direction of former Berlin Symphony and now Munich Philharmonic Orchestra first viola Helmut Nicolai. Also part of the Rosamunde quartet is Andreas Reiner (violin).

“The work is very original and touching. We spent a long time in rehearsal, and the most difficult aspect deals with the uneven proportions of the movements. There is a very long and repetitive slow movement, an extremely short scherzo, and a first movement in the shape of that of a symphony. The writing throughout is of a fine and sensitive quality, it is an extremely well and beautifully sounding work,” explains Reiner.

“It just sounds so wonderful,” he exclaims seconds later, adding: “the scherzo is a first rate quartet virtuoso piece which we will use as an encore in the future. On a very personal note, apart from all sorts of reasoning, I very simply like the quartet. It touches me very much as an original statement of a very special soul.”

The piece was received well by critics and public, which is especially interesting since many did not know who Hans Rott was.The story of Rott is still new to the general public, although he may well become the most important discovery of the changing millennium.

The Rott discovery story starts with Paul Banks, a Mahler scholar from England, the subject of whose 1989 PhD was Mahler’s early years. “Rott was always one of the names who popped up from Mahler’s youth, along with Krzyzanowski, von Kralik etc.” Banks recalls. “One day, I decided to investigate his scores. I got hold of the first symphony he wrote, and I recall siting in the music library in Vienna, unable to believe what I was reading. The piece was brilliant, although not perfect. It was, like Mahler said, as if Rott had aimed for the longest possible throw and not quite reached the mark.”

Rott’s symphony in E major (1878) is typical of Rott’s orchestral music. The instruments used are double woodwind and contra bassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 tromboni, 3 timpani, triangle and strings.

The brass writing alludes to Mahler with its unusually frequent instruction “Mit aufwaerts gerichtetem Schalltrichter” (Banks, 1989).

The symphony has four movements, the slow one being placed second. The second movement is indeed reminiscent of Mahler’s 3rd symphony, and of the last two movements of his sixth. Interesting to note is that the movement begins in A major and ends in E major. Banks (1989) points out that “the scherzo which follows is in C Major. This results in the emphasis of the Emajor/Cmajor juxtaposition heard in the opening movement.”

Banks was the first to recognise the influence on Mahler of Rott’s third movement, “not only in matters of thematic material, but also in questions of formal design.” Although Mahler’s symphonic scherzi are often constructed on a large scale, the third movement of the 5th symphony is certainly the longest (819 bars) and the only example of a scherzo bearing the whole weight of the symphonic structure. It is unique in that the trio is preceded and followed by long transitions” (Banks 1989).

Banks also highlights the importance of Rott as a link between Bruckner and Mahler. Rott was Bruckner’s favourite student and, according to notes by Heinrich Krzyzanowski, destined to become the new Bruckner.

“The character of the main material of Rott’s scherzo is that of a Laendler, the style of which looks back to Bruckner and forward to Mahler’s first symphony. In contrast to Bruckner’s writing, this movement never repeats itself. Rather, the polyphonic writing culminates in a fugato which clearly foreshadows similar passages in Mahler’s fifth symphony.” (Banks 1989)

When Banks spoke to Hyperion records chief Ted Perry about Rott, he decided on a recording, under the direction of Gerhard Samuel, who first performed the symphony in Paris and London in 1989. “I had never heard of Rott until Dr. Banks spoke to me,” recalls Perry. “But when I read the scores, I realised it was too good to be ignored.”

Critics around the world reacted favourably to the 1989 world-premiere performance and recording of the symphony, the feedback ranging from awe to astonishment that such a work could have remained undiscovered until then.

An increasing number of noted scholars and researchers are now working on various aspects of Rott, of whom much remains to be discovered, both musically and biographically. Paris Mahler scholar Isabel Wearck is one of many into whose direction Rott-fan Henri de la Grange pointed. She has recently been involved in some radio programs about Rott, one of which from Germany carried the title “Rott—why knowing him is a must for the serious musicologist.”

Several questions arise from this: who was Hans Rott? What do we know of him, aside from the fact that he wrote a genial symphony and many other brilliant works which we are still to discover and hear performed?

Rott grew up in Braunhirschengrund/Vienna. His early family life was problematic. Rott’s mother Christine died when he was only two years old. His father Karl Mathias was a famous comedy actor at the Theater an der Wien, who had turned to acting after a brief career in music, including a stint as an appointed organist. As an actor, Karl won distinguished honours and awards, including the prestigious “Goldene Verdienstkreuz mit der Kron”.

Rott was Karl’s child from the second marriage, together with his brother Karl. There were also several half siblings from the first marriage. Karl’s third wife, the actress Maria Lutz was thirty years younger than her husband. She died, aged 33, in 1872.

Rott displayed the signs of genius early in life, showing multi-faceted talent. He attended high school and later a commercial business school, from which he graduated with highest recommendations. He began his symphony for strings in 1874, the same year he entered the Vienna conservatoire as a student.

At the conservatoire, Rott took organ classes with Bruckner. He excelled, achieving first grade each year, and winning first prize in the organ competitions of the second and third years.

Bruckner was so impressed with his student that he wrote him a glowing recommendation as an organist to St. Florian in 1878. A notable friendship had developed between Bruckner and his favorite student, causing Bruckner to stand with him in the “cheap” ranks, rather than sit at his place of honour, during performances which they attended together. Rott interrupts one letter to Kzyzanowski, stating that Bruckner had just come to his door to express his consternation at not seeing more of him at the local pub (Kreysing, 1998).

Other studies of Rott include piano with Leopold Landskron. Although he received first grade and won a first prize in 1875, Krzyzanowski reports that both Rott and Bruckner remained questionable piano players, their instrument clearly being the organ.

Rott’s harmony studies began in 1874/5 with Herman Graedner, and counterpoint was studied with Franz Krenn (1875–76). His friends Mahler and Krzyzanowski studied alongside him, but it was Rott who was considered to be the most talented of his circle. The friendship Mahler/Rott was significant, Mahler having spoken about Rott as an important personal and professional influence on him. On one occasion, Mahler’s mother remarked to her son that Rott was the more talented composer of the two.

In 1876/7 Rott took his finals in organ, but began experiencing problems on a personal level. Always a conscientious student, who prided himself in attaining top grades and the approval of his family, Rott’s life was dealt a severe financial and emotional blow with the death of his father in 1876, leaving him orphaned at age 18.

The loss of his father meant severe financial loss for Rott. Following the stage accident of his father in 1874, the Rott family fortune went into steep decline. After the death of his father, Rott was left destitute. According to Krzyzanowski, he suffered hunger in these years. In only a few short years, he had gone from being the well-respected son of a famous actor to becoming a destitute, struggling orphan.

The conservatoire, recognising Rott’s talent and hardship, exempted him from fees in his second year, and awarded him a free place for his third and forth years.

In 1876, he was forced to take up a badly paid post as organist with the Piaristen Monastery in Vienna, as he was also supporting his younger brother Karl. Rott lived mainly of cheap sausages called “Extrawurst”, and suffered from the hostile attitude of the prior. In 1878, he was wrongly accused of theft of a score by the monks, and resigned in outrage. Although this accusation was later cleared, Rott remained deeply wounded by what he sensed was a deep betrayal.

Personal notes of this time show Rott to be a soft personality devoid of ill-will toward anyone, but with a deep need for love and acceptance. His friends and musical acquaintances from the “Akademischer Wagnerverein” gave him this in his early years. He joined there in 1876, the Verein including such notable names as Mahler and Wolf.

Rott was unwilling to align himself with the streams of his time, and stood alone as an individualist. He admired and studied the music of Brahms, Bruckner and Wagner, refusing to choose one to the exclusion of the others. Elements of all three are reflected in his music, most of which has been preserved and which ranges from symphonies to chamber music and songs.

As his finances declined, disappointment in his fellow men mounted after a betrayal by his close friend Rudolf Krzyzanowski. Rott withdrew more into himself and his music. Financially, he was supported mainly by Friedrich Seemueller, with whom he spent a serene last vacation in 1880 in rural lower Austria.

Rott was ashamed at being financed by Seemueller, which is shown in his notes. In early 1880, he suffered emotionally on three counts: his lack of immediate family, the rejection of his art and finally, an unhappy love affair.

Not much is known as present about the love affair which remains a crucial missing link to Rott’s story. His notes indicate that he fell in love with a woman named Louise, who either rejected him or initially loved him back but was promised to someone else and then forced to reject him. All notes so far indicate that Rott was a virgin at the time of his death, loyal to Louise, for whom he wrote the symphony in E Major.

His financial situation and shame forced Rott to accept a post outside Vienna. He was offered a position as choirmaster in Muehlhausen (Mullhouse) in Alsace but in 1880 made a last ditch effort to remain in Vienna.

Vienna was extremely important to Rott, who had grown up there and had no family to return to once he left. Also, Vienna was Louise’s hometown, and he clearly hoped to stay close to her. Rott believed that he had to “save” Louise from an unhappy, possibly forced marriage she was about to enter into.

His plan was to win the Beethoven competition with his symphony in E Major, and to further this aim he visited Brahms in 1880. Alluding to the similar elements found in the finale of Rott’s symphony to his own C Minor symphony, Brahms harshly stated that Rott could not have possibly written the work himself and told the young composer that he had no talent whatsoever. During the competition, the symphony was laughed at by the jury, which included Goldmark and Brahms. Bruckner was incensed at its members, predicting that “you will hear great things yet from this young man.”

Shaken, but encouraged by Bruckner not to give in, Rott wrote a pleading letter to Hans Richter, outlining his despair at the prospect of leaving Vienna. He expressed the hope that Richter would include the symphony in the programme of the Philharmonic Orchestra and thus enable him to find an alternative income.

Richter met with Rott after several delays, on October 14, 1880, and expressed himself favourably about the symphony, encouraging Rott to keep composing. But he was not willing to incorporate this early work in the programme of the Philharmonic Orchestra.

Rott must have become convinced that Brahms was conspiring against him, jealous of his talents as a musician. Forced to accept the posting at Mullhouse, on the train there Rott used his pistol to keep a fellow passenger from lighting a cigar because “Brahms had fixed the train with dynamite.” He was taken to the Landesirrenanstalt (insane asylum), where he was interned as a patient of the lowest, non-paying class, and died of tuberculosis within three and a half years, on June 25, 1884.

Little is known of Rott’s time at the clinic, except that he kept composing and that he was visited by his friends. He had applied for a state stipend prior to leaving Vienna, but had not heard back from the board. Now, too late, the stipend was awarded to him. A surviving letter of Rott from the asylum to the music director of Mullhouse where he officially renounces the post as choir director, expresses his hope of getting well again and of being able to stay in Vienna.

Rott’s funeral on June 28, 1884 at the Zentralfriendhof Vienna was attended by Anton Bruckner, who arrived early and spent a significant amount of time alone with the coffin of his young friend. At the funeral itself, Bruckner was seen crying, and stated openly that Brahms’ uncalled-for, harsh treatment of an already isolated young composer was to blame for his demise.

Today’s Vienna shows little evidence of the tragedy which took place there some 100 years ago, without which our perception of music from that time may have well changed from Bruckner, Brahms, Mahler to Bruckner, Brahms, Rott, Mahler.

The Piaristenkloster still stands, but it has been painted a new colour. The organ where Bruckner and later Rott played is still there, and another organist now touches the same keys. One can walk up to it on the same steps Rott and Bruckner once walked, and look out over the courtyard, the same view they once enjoyed. At night, an outdoor café makes it possible to sit in the courtyard of the abbey, imagining the sights and sounds Rott must have heard during his short nights spent sleeping there before getting up for the 6 am mass. The interior garden remains largely the same, and one gets an idea of Rott’s retreat at times when he wanted to get some peace and quiet between composing his own works and performing for the Piaristen.

Rott’s last dwelling at the Rothenturmstrasse has been bombed in the war, and later rebuilt into a business complex. Neither his room nor his home can be made out, but Bob Freeman and myself are greeted by an insurance company’s secretary who has never heard of Rott nor Mahler.

The cemetery where Bruckner once cried for Rott is still the same. But Rott’s grave, after the cemetery officials initially insist that he is not buried where he is supposed to have been buried, turned out to have been re-used. It now houses some family called Schwarz. Not even a stone remains to indicate that the body of Hans Rott is buried there, beneath them.

The insane asylum where Rott was interned and died still stands, but it has been completely rebuilt and modernised. All documents have been destroyed which pertain to Rott. Surviving documents about the former head of the clinic and Rott’s attending physician, Dr. Theodore Meynert, give some indication of conditions there.

A visit to the Institute for History of Medicine shows that only in the 1850s torture was abandoned as a means of treating mental patients. Rott found slightly better conditions, which had changed, from the attitude that physical pain ought to be inflicted regularly on mental patients to keep them from brooding, to one of indifference.

Records indicate that a short stay at the asylum of a student named Sigmund Freud, which had taken place during Meynert’s and Rott’s time, ended in conflict between Meynert and Freud over Meynert’s rejection of psychotherapy as a treatment option. Records show that during Rott’s time, Meynert experienced the onset of mental instability himself, which caused him to keep his dead son’s heart in a glass on his desk and also affected the attitude to his patients. Records further indicate that insufficient isolation between tuberculosis and regular patients at the clinic could have led to Rott contracting the disease, which later caused his death.

A visit to the dusted archives of the Meynert clinic shows a high death rate from “natural causes” for physically healthy, young patients. This may be indicative of conditions or treatment methods at the clinic. Indicative could also be the resignations of several staff who found themselves unable to deal with conditions at the clinic of the noted brain anatomist.

A short walk to the grocer across the road from the archive reveals that “Extrawurst”, the impoverished Rott’s main means of sustenance, still exists. It can be bought for a couple of shillings, and tastes rather good as it is laced with garlic.

A visit to the Musiksammlung reveals Rott’s handwritten, personal papers and scores. He practised calligraphy frequently, conscious of his neatness, and did his shopping list on the sides of his scores which he clearly felt were of no use to anyone aside himself. A note in which Rott speaks of the fear of losing his mind highlights his increasing isolation, the pain of not having a family to call his own, and states his inability to continue living without love while composing just for the sake of it, without anyone taking notice.