- Profession: Director New York Metropolitan Opera (MET).

- Residences: Vienna, Bremen, New York.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 03-09-1855 Bielitz, Austria.

- Died: 27-04-1909 Merano, Austria (Italy).

- Buried: 13-05-1909 Cypress Hills cemetery, Brooklyn, America. Grave ?

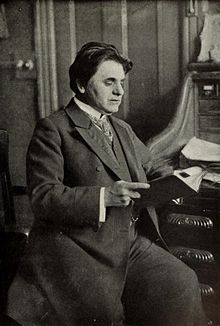

Heinrich Conried was a theatrical manager and director of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Born into a Silesian weaver family of Jewish origin he received his education at the Realschule in Vienna. Early on, he was an actor in at the Burgtheater in Vienna. Only 21 years old he became manager of the failed Bremer Stadttheater. His success in rescuing the theater not only moved the Senate of the city to pass a resolution thanking him, but also brought him to the attention of Adolf Neuendorff, who was the manager of the Germania Theatre in New York. On invitation of Neuendorff Conried moved in 1878 to New York City, where he became chief stage manager of the Germania Theatre. In 1881 he moved to the Thalia Theatre as artistic manager and in 1882 he became artistic manager of the New York Concert Company.

In 1893 he assumed the management of the Irving Place Theatre. In 1903, he succeeded Maurice Grau as director of the Metropolitan Opera (until 1908). His first season at the Met was notable through the first production of Parsifal outside of Bayreuth, against the wishes of Cosima Wagner, who went to court but failed in her attempt to forbid the production.

By December 31, 1913, when the copyright of Parsifal expired, the work had been represented 43 times at the Metropolitan Opera. Enrico Caruso (1873-1921), who until then had refused all offers to come to America, was persuaded by Conried to come to New York and sing at the Met. Soon after he had become director of the Metropolitan Opera, he conceived the New Theatre. On May 1, 1908 he retired from the Metropolitan Opera House due to his poor health. Immediately afterwards he voyaged to Europe. He died on April 27, 1909 in the Hotel Meranerhof in the city of Meran from an apoplectic stroke in the presence of his wife and sister.

Funeral

On March 30th he was at the Hotel Du Cap Ampeglio Bordighera, Italy, and, finding no relief from the pain which so constantly weakened him, he returned to Meran (Merano), where he was stricken with paralysis, and with inflammation of the lungs. Here it was that he died on April 27, 1909. Even in his death, the Metropolitan Opera House profited, in as much as his life was insured by them for $150,000.

No sooner did the news of Mr. Conried’s death reach America than pressure was imme-diately brought to bear on Mrs. Conried to consent to a public funeral. She finally cabled her willingness, and Johann Andreas Dippel (1866-1933), then https://mahlerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MF-Projects-2.pngistrative manager of the Metropolitan, in the name of the Directors, offered the Opera House.

On May 11th, the S.S. Kronprinzessin Cecilie, carrying Conried’s body, Mrs. Conried, and their son Richard, arrived in New York. This trip back was to have been the Impresario’s hundredth voyage, and his death came as a personal loss to the Directors of the line. A dramatic coincidence was the Cecilie’s meeting, as she approached her pier, the outward-bound Kronprince Wilhelm, carrying many artists who had sung at the Metropolitan under Conried’s management — Scotti, Zenatello, the tenor lent by Hammerstein, Maria Gay, and Geraldine Farrar, whom Conried had first presented. The body was taken to the Conried home, where it remained until May 13th, the date set for the funeral.

Four thousand invitations to the services were issued, and the supply was immediately exhausted. At least twice that number of per- sons endeavored to gain admittance, while a body of police tried to keep the crowds in or-der. The funeral cortege passed down Broadway toward the Metropolitan Opera House, and people stood on the sidewalk with uncovered heads all along the route. The doors of the Metropolitan were opened some time before the hour set for the services. The immense auditorium was in darkness, except for the stage, and the great crowd waited in silence. The stage itself was set for the second act of Verdi’s “Falstaff,” with added funereal touches, most conspicuously placed in the centre of the stage being a catafalque of six steps, covered with black cloth, and standing seven feet high. It took over four thousand yards of black crepe to cover the proscenium arch. The catafalque was literally banked in floral decorations and cut flowers.