- Gustav Mahlers’ winter trip to a bell foundry in Zehlendorf.

- Year 1895.

- 08-12-1895 Letter to Anna Bahr-von Mildenburg (1872-1947) about the trip.

- Bells for the premiere of Gustav Mahlers Symphony No. 2 in Berlin: 1895 Concert Berlin 13-12-1895 – Symphony No. 2 (Premiere).

- Three deep bells of unspecified pitch.

- History Symphony No. 2.

- Orchestration Symphony No. 2.

- Movement 5: “Aufersteh’n”. Im Tempo des Scherzos. Wild herausfahrend. In the Leipziger ‘Neue Zeitung fur Musik’: A row of big bells were hanging on a wooden frame.

Gustav Mahler travelled in half an hour by train from Berlin to Zehlendorf and stayed about two hours.

Mahler probably met Johann Heinke (Bell foundry meister, Mittelstrasse 1 in Zehlendorf, assistent of Gustav Collier).

He purchased church bells for the first performance, finding all other means of achieving this sound unsatisfactory. He wrote of this final movement: ‘The increasing tension, working up to the final climax, is so tremendous that I don’t know myself, now that it is over, how I ever came to write it.’

Collier foundry

- 1875: Charles Collier moved in 1875 from Berlin North to Zehlendorf (West).

- 1883: The factory was finished.

- 1893: Wilhelm II had visited the foundry.

- 1895: Gustav Louis Guillaume Collier (1845-1908) was a bell founder working in the Berlin area and bells from the foundry can be found in a wide area around the German capital.

- 1895: Collier, bell foundry workshop in Zehlendorf, Glockenstraße 2 (Glockenstrasse 2, Bell Street No. 2) near the old village.

- 1895: Gustav Mahler visited the foundry. He probably met Johann Heinke (Bell foundry meister, Mittelstrasse 1 in Zehlendorf, assistent of Gustav Collier).

- 1914: Production of cannons.

- 1918: Last Collier died on the France Front. Factory closed. Some 3000 bells were casted by the Colliers.

In a letter from Berlin 08-12-1895 to Anna Bahr-von Mildenburg (1872-1947), Gustav Mahler described very graphically and with a certain comfortable cheerfulness his efforts at finding the necessary instruments for the bell sounds.

The letter is characteristic for the care that Mahler devoted to the correct realization of his intentions. It also shows that Mahler did not use special sound effects because of a practica experience with some new instrument, but rather that the idea of the sound was there for him first and that only later did the question come up about its realization.

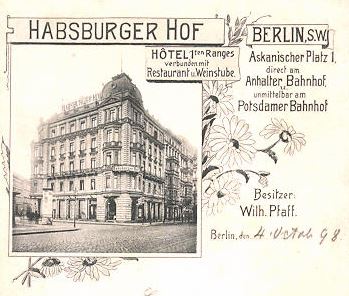

“I need for my symphony,” he writes, “as you know, at the end of the last movement, bell sounds that can be executed by no musical instrument. Hence, I thought from the outset that only a bell founder could help me.Now, I finally discovered such a founder; to reach his workshop, one must travel about a half an hour by train. It is in the vicinity of Grunewald. I headed off very early in the morning, it had snowed beautifully, and the frost enlivened my somewhat depressed body and spirit, for I had also slept little that night. As I arrived in Zehlendorf — that is what the place is called — and sought my way through firs and spruces completely covered with snow, everything very rural, a lovely church joyously gleaming in the winter sunshine, my heart became full and I saw how free and happy a man suddenly becomes when he comes back again out of the unnatural and restless bustle of the great city into the quiet house of nature . . .

After a prolonged search, I discovered the foundry; I was received by a simple old gentleman with fine white hair and beard and such peacefully friendly eyes, that I suddenly felt as if I had been transported to the times of the old master guild. Everything was dear and beautiful to me. I spoke with him, and he was certainly somewhat verbose and slow to me, the impatient one. He showed me glorious bells, among others a great and mighty one that he had cast on order of the German emperor for the new cathedral. The sound was mysterious and powerful. I had thought of something similar for my work. But the times are already long past when only the most costly and the most significant things are good enough to serve a great work of art. So I looked for a few somewhat more modest bells that would nonetheless be sufficient for my purposes, and said goodbye after a stay of about two hours with the dear old one. The way back was again glorious.

But now back to the general management: the lobbying was in full force. These faces! These bony people! Every inch of their faces carried the traces of the self-tormenting egoism that makes all men so unhappy! Always I and I—and never Thou, Thou my brother!”

Bell in 1892 produced by Bell foundry Collier.