- Address: Piccadilly 28, Regent street 73, Viene Street.

- 2,127 seats.

- Gustav Mahler himself in London (1892).

- Year 1892.

Conducted by Gustav Mahler:

St. James’s Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25-03-1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, and Vine Street and George Court. There was a frontage on Regent Street, and another in Piccadilly:

London. St. James’s Hall. Map.

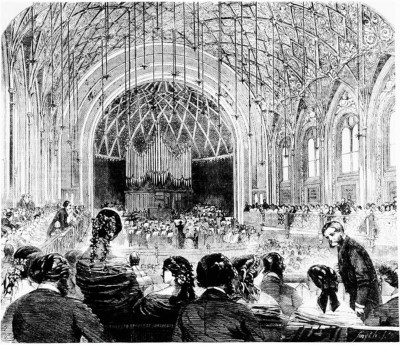

1858. London. St. James’s Hall. Opening.

Taking the orchestra into account, the main hall had seating for slightly over 2,000 persons. It had a grand hall 140 feet (43 m) long and 60 feet (18 m) broad, the seating was distributed between ground floor, balcony, gallery and platform and it had excellent acoustics. On the ground floor were two smaller halls, one 60 feet (18 m) square; the other 60 feet (18 m) by 55 feet (17 m).

The Hall was decorated in the ‘Florentine’ style, with features imitating the great Moorish Palace of the Alhambra. The Piccadilly facade was given a Gothic design, and the complex of two restaurants and three halls was hidden behind Nash’s Quadrant. Sir George Henschel recalled its ‘dear old, uncomfortable, long, narrow, green-upholstered benches (pale-green horse-hair) with the numbers of the seats tied over the straight backs with bright pink tape, like office files.’

1885. London. St. James’s Hall.

The Hall was built jointly by two music publishing firms, Chappell & Co. and Cramer & Co., in the hope of attracting the growing audiences for fine musical performances that attended the Crystal Palace and the halls being built in the provinces. It stood empty for nearly a year after its opening. For almost half a century thereafter, the Hall was London’s principal concert hall, to be succeeded by Queen’s Hall in the 1900s and later by Wigmore Hall, the Royal Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall. It became famous for its ‘Monday Pops’ concerts and Ballad Concerts, as the home of the Philharmonic Society and the Christy Minstrels and for the many famous conductors and performers who gave important performances there.

F. H. Cowen succeeded Sullivan as conductor from 1888-1892. In his first season Edvard Grieg played his Piano Concerto in A minor and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky made his first appearance before an English audience, introducing two works. Johan Svendsen and Charles-Marie Widor also conducted in that season, and Clara Schumann made her farewell performance to the Society. Tchaikovsky returned in 1889 to conduct his Piano Concerto No. 1 with Wassily Sapellnikoff making his English debut (who three years later created a furor with the Liszt E flat concerto); and Agathe Backer-Grøndahl and Eugène Ysaÿe also made their English debuts.

In 1890, Dvo?ák conducted his Fourth Symphony. Paderewski, who gave four recitals at St. James’s Hall for his début in 1890, returned there for the Society in 1891 to perform the Saint-Saëns’ C minor, and the Rubinstein D minor, concerti. Leonard Borwick and Frederic Lamond also performed there for the Society. Cowen gave many concerts of contemporary English composers such as Sullivan, Hubert Parry, Alexander Mackenzie, Charles Villiers Stanford, and of his own works.

Gustav Mahler: 1892 Concert London 29-06-1892.

In 1892 Alexander Mackenzie succeeded Cowen. In the 1893 season, Tchaikovsky gave the English premiere of his Fourth Symphony, Saint-Saëns conducted his Le Rouet d’Omphale and played his G minor concerto, and Max Bruch conducted his own Second Violin Concerto with Ladislas Gorski as soloist. In November 1893, a presentation was made to the Society’s Secretary Francesco Berger in appreciation of ten years service. Soon afterwards, Queen’s Hall opened its doors, and the Society moved there in the following February.

The Chappell ballad concerts were being managed by William Boosey in 1902, when the hall was owned by a private company. The controlling share was held by T. P. Chappell, chairman of Chappell’s: he turned down a good offer to buy the hall because Boosey felt strongly about its old connection with the Saturday and Monday ‘Pops’ and the Chappell ballad concerts. But Chappell died in June 1902, and the other shareholders accepted a new offer without consulting Boosey, who was badly put out. Then Queen’s Hall came into the market, and a friend of Boosey’s acting in that interest pointed out that Queen’s Hall would be worth much more if St James’s Hall ceased to operate.

Boosey realised that Messrs Chappell could benefit most by becoming lessors of Queen’s Hall, and it was immediately arranged with the result that Chappell’s controlled Queen’s Hall from 1902 down to 1944. The 11-year-old violinist Franz von Vecsey made his English debut at St James’s Hall in April or early May 1904. It continued in use until February 1905 when it was demolished. The Piccadilly Hotel was afterwards built on the site.

More on The St. James’s Hall, Piccadilly

In 1853 Charles Moreing of No. 14 Regent Street, architect, entered into articles of agreement with the Commissioners of Woods and Forests whereby he undertook to repair or rebuild No. 28 Piccadilly and the extensive workshops situated behind. Subsequently Moreing acquired several adjacent small houses in Vine Street and George Court (both now Piccadilly Place) and in 1855 he was negotiating for the sale of his interest to a public company which was to be formed for the purpose of erecting a large concert hall there. The provisional committee of the St. James’s Hall Company, which was formed about this time, included William Chappell and T. F. Beale, musical publishers, (Sir) Julius Benedict, conductor, and John Ella, violinist and concert director.

In its prospectus the company stated that ‘The growing taste for Musical Performances of a high order, and upon an extensive scale, renders it necessary that some suitable provision should be made at the West End of London for such entertainments’. The need for a hall had long since been supplied in Liverpool, Birmingham and elsewhere, but ‘the Metropolis remains singularly deficient in proper accommodation for such performances. . . . The proposed building will be expressly designed with a view to aid the effect of instrumental and choral performances.’

In November 1855 the company’s architect, Owen Jones, submitted designs for a public building to be called St. James’s Hall, and in February 1857 the Commissioners approved them. Shortly afterwards the company acquired the leases of Nos. 69, 71 and 73 Regent Street, which abutted on the north side of the site of the hall. This valuable addition was used to provide an extra entrance to the hall, and a first-class restaurant.

The St. James’s Hall, which for nearly half a century was to be London’s principal concert hall, was erected in the centre of the block now occupied by the Piccadilly Hotel, and possessed access to Piccadilly on the south and Regent Street on the north (fig. 7). On the ground floor there were two small halls, above which stood the great hall. Owen Jones had been superintendent of the works at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and it was therefore not surprising that, in the opinion of The Builder, his design displayed novelties of construction which may ‘be found to belong to the commencement of an alteration in the current practice of building. We refer especially to the use of iron, less as an auxiliary than as a main element in the framework of a structure.’. The builders were Messrs. Lucas. The St. James’s Hall was opened on 25 March 1858, with a charity concert in aid of the Middlesex Hospital.

The three concert halls were contained in an oblong building some 140 feet in length from east to west, and 75 feet in width, including the corridor along the south side. In the ground storey were two halls of similar size, the east hall being planned in the form of a wide but short-armed cross with galleries in its east, north and south arms. The west hall was an oblong with a gallery on its long east side and a platform recessed into the west wall. The oblong body of the great hall on the first floor was some 95 feet long and 57 feet wide. A straight-fronted gallery extended along the north and south sides, and across the east end. Each long side wall was divided by piers into eight equal bays, and in each end wall was a great arch, 38 feet wide, the west opening to an apse containing choir seating and an organ, and the east opening to the back stalls and the gallery.

The architectural scheme and decoration of the great hall, designed by Owen Jones, must have been impressive and in many ways beautiful. There was probably little of interest below the gallery, which had a railing of cast iron, with geometrical frets in panels, rather Moorish in character. In every bay of the side walls was a tall round-arched recess, containing a decorative panel below a ‘Florentine’ window of two lights, the marginal frames of these recesses being decorated with ‘flowing scroll ornaments, on a ground of orange-chrome yellow’. The round arches were, in turn, set in recesses with two-centred arches, forming tympana that were modelled with ‘groups of figures in bold relief, holding scrolls on which are inscribed the names of Mozart, Handel, Beethoven, Haydn, Auber, Meyerbeer, Spohr, Weber, Gluck, Purcell, Rossini, Cherubini, and other eminent composers’.

On the piers between these pointed arches were slender colonnets, supporting the ribs outlining the groins over the recesses, and traversing the surface of the great semi-circular barrel-vaulted ceiling, forming a pattern of lozenge-shaped panels over which smaller lozenges were placed, the whole being decorated with arabesques ‘rich in colour and gilding; the smaller panels . . . Alhambran gold on a red ground’. The wide marginal surrounds of the great east and west arches were simply treated, being divided by ribs into three concentric bands, and the semi-dome of the western apse was divided by interlacing ribs into a pattern of lozenges, diminishing in size towards the crown. The hall was ‘not lighted at night by a central chandelier, but by gas stars of seven jets each, suspended from the ceiling. The figures in the various designs were modelled by [Raphael] Monti; the other enrichments, by De Sarchy, are of plaster and canvas run into moulds’. The floor of the hall was of marqueterie.

London. St. James’s Hall, ground floor and first floor.

The narrow front towards Piccadilly, designed by Owen Jones, was a highly original composition, decidedly eclectic in style (Plate 30a). The twin doorways, and the two windows of the first and second floors, were recessed within a tall round-headed arch with a strongly moulded reveal. This arch was set in a plain face finished with a Graeco-Egyptian cornice and crested with anthemion ornament. The infilling of the arch was very elaborate, with ‘Florentine’ windows of cast iron, their arched heads springing from curiously detailed colonnets. Below the upper pair of windows were apron panels with a high relief decoration of putti, and in the tympanum of the arch was a relief symbolizing music.

Many famous musicians appeared at the St. James’s Hall, including Dvorák, Grieg, Liszt, Paderewski, Saint-Saëns, Sullivan and Tchaikovsky. The acoustics of the building were extremely good, but the seats were uncomfortable and kitchen odours from the restaurant sometimes floated into the auditorium. Worse still, the sound of the Moore and Burgess Minstrels (who performed in one of the smaller rooms for over twenty years) could sometimes be heard upstairs in the main hall.

The catering side of the business was greatly enlarged in 1874-1875 by the acquisition and rebuilding of Nos. 24–26 (consec.) Piccadilly, with a street-frontage of some forty-five feet. The new building contained buffets, grill-and dining-rooms and offices, and could be entered from the concert halls. The dining-rooms are said to have been ‘notable as having been perhaps among the first in the metropolis to possess each a small kitchen of its own—an indispensable adjunct to hot and rapid service’. The building was designed by Walter Emden and was in the Venetian Gothic style, the materials used for the Piccadilly elevation being red brick, Dumfries stone, red terra-cotta and mosaic on a gold ground.

The general contractors were Lucas Brothers of Lambeth; the masonry and stone carving was by William Plows, the mosaics by Alexander Gibbs, and the terra-cotta by Messrs. Johnson and the Ditchling Potteries. The Piccadilly front was four storeys high, not counting the mezzanine, and must have been very colourful with its wide variety of materials employed. The windows of the ground, first and second floors were grouped in pairs on each side of a single light, and all were dressed with slender colonnets and, apart from the ground-floor lights, with cusped arches. The third-floor windows were recessed behind a ‘Ca’d’Oro’ gallery.

The main entrance to the hall from Piccadilly was entirely rebuilt in 1882-1883, with a slightly wider frontage. The architect was again W. Emden, whose designs on this occasion were ‘after the Early English style, without any very strict adherence to old examples’. The front may more accurately be described as curiously French in character, with its trio of gabled doorways, and the high attic above the central feature, flanked by tourelles and crowned with a steep ‘chisel’ roof. The top of the building stood over a hundred feet above the pavement. The contractor was Herbert Lea of Warwick Street.

In 1885 the Metropolitan Board of Works decided that the hall was ‘so defective in its structure that special danger from fire may result to the public frequenting the same’, and therefore required the company to make thirty modifications, mostly in order to improve access. In 1899 the London County Council required a further twenty-nine alterations. At about the same time the Council was also considering the widening of the north side of Piccadilly between the Circus and Sackville Street, and the company therefore decided to modernize their premises and make very extensive alterations.

Gustav Mahler: 1892 Concert London 29-06-1892

In 1901 the company signed an agreement with the Commissioners of Woods and Forests whereby it was to undertake heavy structural expenditure in return for a new lease of all its property.

But the St. James’s Hall no longer enjoyed its old pre-eminence in musical affairs (the Queen’s Hall had been opened in 1893 and the Wigmore (then called the Bechstein) Hall in 1901) and it was probably not making a large enough profit to justify the high rent which the Crown would have demanded after the renewal of the lease. In 1903 the company therefore sold the benefit of their building agreement of 1901 with the Office of Woods to the P. and R. Syndicate, whose intention was to demolish the hall and erect a large first-class hotel. The St. James’s Hall continued in use until February 1905, when it was demolished to make way for the Piccadilly Hotel.

2016. London. Vine Street. St. James’s Hall.

2016. London. Vine Street and Swallow Street. St. James’s Hall.

2016. London. Regent Street near Air Street. St. James’s Hall.

2016. London. Air Street alley. St. James’s Hall.