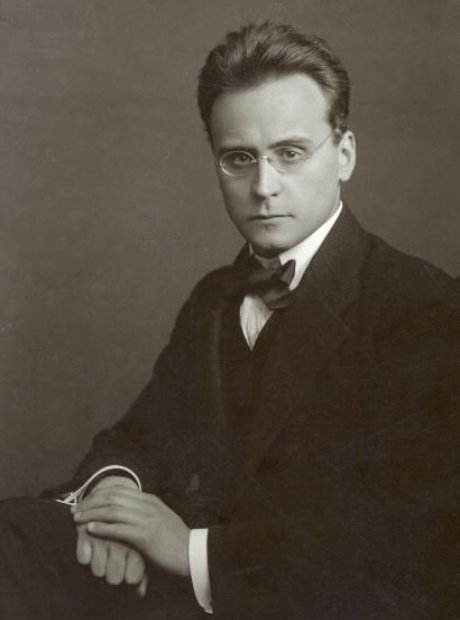

- Profession: Composer.

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 03-12-1883 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 15-09-1945 Mittersill, Salzburg, Austria.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Mittersill cemetery, Zell am See Bezirk, Salzburg, Austria.

Anton Webern was an Austrian composer and conductor. He was a member of the Second Viennese School. As a student, significant follower of, and influence on Arnold Schoenberg, he became one of the best-known exponents of the twelve-tone technique. His characteristically unique innovations regarding schematic organization of pitch, rhythm and dynamics were formative in the musical technique later known as total serialism, so much so as to focus the attention of his posthumous reception in a direction away from, if not apparently antithetical to, his affiliations with German Romanticism and Expressionism.

Youth and education in fin-de-siècle Vienna, Austria-Hungary

Webern was born in Vienna, Austria, as Anton Friedrich Wilhelm (von) Webern. He was the only surviving son of Carl von Webern, a civil servant, and Amelie (née Geer) who was a competent pianist and accomplished singer—the only obvious source of the future composer’s talent. He never used his middle names and dropped the “von” in 1918 as directed by the Austrian government’s reforms after World War I. After spending much of his youth in Graz and Klagenfurt, Webern attended Vienna University starting in 1902. There he studied musicology with Guido Adler, writing his thesis on the Choralis Constantinus of Heinrich Isaac. This interest in early music would greatly influence his compositional technique in later years, especially in terms of his use of palindromic form on both the micro- and macro-scale and the economical use of musical materials.

He studied composition under Arnold Schoenberg, writing his Passacaglia, op. 1 as his graduation piece in 1908. He met Alban Berg, who was also a pupil of Schoenberg’s, and these two relationships would be the most important in his life in shaping his own musical direction.

Red Vienna in the First Austrian Republic

After graduating, he took a series of conducting posts at theatres in Ischl, Teplitz (now Teplice, Czech Republic), Danzig (now Gda?sk, Poland), Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland), and Prague before moving back to Vienna. There he helped run Schoenberg’s Society for Private Musical Performances from 1918 through 1922 and conducted the “Vienna Workers Symphony Orchestra” from 1922 to 1934.

In 1926 Webern noted his voluntary resignation as chorusmaster of the Mödling Men’s Choral Society, a paid position, in controversy over his hiring of a Jewish singer, Greta Wilheim, to replace a sick one. Letters document their correspondence in many subsequent years, and she (among others) would in turn provide him with facilities in which to teach private lessons as a convenience to Webern, his family, and his students.

Civil War, Austrofascism, Nazism, and World War II

Your ‘avowal of faith’ has given me extraordinary joy, your avowal of the viewpoint that art has its own laws and that, if one wants to achieve something in it, only these laws and nothing else can have validity. However, as we recognize this we also sense that, the greater the confusion becomes, the graver is the responsibility placed on us to safeguard the heritage given us for the future.

Webern’s music, along with that of Berg, K?enek, Schoenberg, and others, was denounced as “cultural Bolshevism” and “degenerate art” by the Nazi Party in Germany, and both publication and performances of it were banned soon after the Anschluss in 1938, although neither did it fare well under the preceding years of Austrofascism. As early as 1933, an Austrian gauleiter on Bayerischer Rundfunk mistakenly and very likely maliciously characterized both Berg and Webern as Jewish composers. As a result of official disapproval throughout the ’30s, both found it harder to earn a living; Webern lost a promising conducting career which might have otherwise been more noted and recorded and had to take on work as an editor and proofreader for his publishers, Universal Edition (UE) music publishers. His family’s financial situation deteriorated until, by August 1940, his personal records reflected no monthly income. It was thanks to the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart that Webern was able to attend the festive premiere of his Variations for Orchestra, op. 30 in Winterthur, Switzerland in 1943. Reinhart invested all the financial and diplomatic means at his disposal to enable Webern to travel to Switzerland. In return for this support, Webern dedicated the work to him.

There are different descriptions of Webern’s attitude towards Nazism; this is perhaps attributable either to its complexity, his internal ambivalence, his prosperity in the preceding years (1918–1934) of post-war Red Vienna in the First Republic of Austria, the subsequently divided political factions of his homeland as represented in his friends and family (from Zionist Schoenberg to his Nazi son Peter), or the different contexts in which or audiences to whom his views were expressed. Further insight into Webern’s attitudes comes with the realization that Nazism itself was deeply multifaceted, marked “not a coherent doctrine or body of systemically interrelated ideas, but rather [by] a vaguer worldview made up of a number of prejudices with varied appeals to different audiences which could scarcely be dignified with the term ‘ideology.'”

In broad terms, Webern’s attitude seems to have first warmed to a degree of characteristic fervor and perhaps only much later, in conjunction with widespread German disillusionment, cooled to Hitler and the Nazis; but he was no antisemite. On the one hand, Willi Reich notes that Webern attacked Nazi cultural policies in private lectures given in 1933, whose hypothetical publication “would have exposed Webern to serious consequences” later. On the other, some private correspondence attests to his Nazi sympathies, though he denied these to Schoenberg when asked (only once), who heard rumors, never confirmed to him by Rudolf Kolisch and Eduard Steuermann, denied to him by Louis Krasner, and then very strenuously denied to him by Webern.(As such, Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto of 1934 (or 1935)–36 continued to bear a dedication to Webern.) Webern’s patriotism led him to endorse the Nazi regime, for example, in a series of letters to Joseph Hueber, who was serving in the army and himself held such views. Webern described Hitler on May 2, 1940 as “this unique man” who created “the new state” of Germany; thus Alex Ross characterizes him as “an unashamed Hitler enthusiast”.

Musicologist Richard Taruskin describes Webern accurately if vaguely as a pan-German nationalist but then goes much further in claiming specifically that Webern joyfully welcomed the Nazis with the 1938 Anschluss, at best extrapolating from the account of his cited source Krasner and at worst exaggerating or distorting it, as well as describing it sardonically as “heart-breaking.”Taruskin’s authority on this delicate issue must be credited, if at all, then only with the significant limitations that he has been polemical in general and hostile in particular to the Second Viennese School, of whom Webern is often considered the most extreme and difficult (i.e., the least accessible).

In contrast to Taruskin’s methods and pronouncements, musicologist Pamela M. Potter advises that “[i]t is important to consider all the scholarship on musical life in the Third Reich that, taken together, reveals the complexity of the day-to-day existence of musicians and composers,” as “[i]t seems inevitable that debates about the political culpability of individuals will persist, especially if the stakes remain so high for composers, for whom an up or down vote can determine inclusion in the canon.” In this vein, it might be noted in relation to Taruskin’s claim that Webern wrote to friends (husband and wife Josef Humplik and Hildegard Jone) on the day of Anschluss not to invite celebration or to observe developments but to be left alone: “I am totally immersed in my work [composing] and cannot, cannot be disturbed”; Krasner’s presence could have been a disturbance to Webern for this reason, and musicologist Kathryn Bailey speculates that this may indeed be why he was rushed off by Webern.

There is, moreover, significant political complexity to be treated, more than enough to complicate any consideration of individual culpability: it is imperative to note that some Social Democrats viewed the National Socialists as an alternative to the Christian Social Party and later Vaterländische Front in the context of reunification with Germany; for example, Karl Renner, a chancellor who served in both the First (1919–33) and Second (post-1945) Austrian Republics, favored a German Anschluss as an alternative to the then Austrofascist regime, under which Berg, Webern, and the Social Democrats suffered. And Webern’s professional circle in Vienna included, besides many Jews, many Social Democrats; for example, for David Josef Bach, a close friend of Schoenberg’s as well, Webern conducted many workers’ and amateur ensembles. Under the Nazis, some Social Democrats expected, there might be more work and protections for workers and laborers, as well as other social reforms and political stability, if not democracy; Webern may well have hoped to again be able to conduct and to be better able to secure a future for his family.

Krasner himself painted not a sentimental portrait but one imbued with a wealth of factual and personal detail for its publication in 1987, describing Webern as clearly naive and idealistic but not entirely without his wits, shame, or conscience; Krasner carefully contextualizes Webern as a member of Austrian society at the time, one departed by Schoenberg and one in which the already pro-Nazi Vienna Philharmonic had even refused to play the late Berg’s Violin Concerto. As Krasner vividly recalled, he and Webern were visiting at the latter’s home in Maria Enzersdorf, Mödling when the Nazis invaded Austria; Webern, uncannily seeming to anticipate the timing down to 4 o’clock in the afternoon, turned on the radio to hear this news and immediately warned Krasner, urging him to flee immediately, whereupon he did (to Vienna). Whether this was for Krasner’s safety or to save Webern the embarrassment of Krasner’s presence during a time of possible celebration in the pro-Nazi Webern family or indeed in most of pro-Nazi Mödling, by Krasner’s description, Krasner was ambivalent and uncertain, withholding judgment. Only later did Krasner realize how self-admittedly “foolhardy” he had been and in what danger he had placed himself, revealing an ignorance perhaps shared by Webern. Krasner had even revisited frequently, hoping to convince friends (e.g., Schoenberg’s daughter Gertrude and her husband Felix Greissle) to emigrate before time ran out.

Moreover, Krasner retold from a story related to him in long discussion with Schoenberg’s son Görgi, a Jew who remained in Vienna during the war, that the Weberns, much to their risk and credit, had provided Görgi and his family with food and shelter toward the end of the war at the Weberns’ home in a Mödling apartment belonging to their son-in-law. Görgi and his family were left behind for their safety when Webern fled on foot with his family to Mittersill, about 75 km. away, for safety of their own in light of the coming Russian invasion; Amalie, one of Webern’s daughters, wrote of ’17 persons pressed together in the smallest possible space’ upon their arrival. Ironically, the Russians pronounced Görgi a “Nazi spy” when he was discovered due to the Nazi munitions and propagranda in the Weberns’ basement store-room. Görgi is said to have saved himself from execution by protesting and drawing attention to his clothes, sewn as specified by the Nazis with the yellow Star of David. He continued to live in this apartment with this family until 1969.

Webern is also known to have aided Josef Polnauer, a Jewish friend who, as an albino, managed to largely escape the Nazis’ attention and later edit a publication of Webern’s correspondence from this time with Hildegard Jone, Webern’s then lyricist and collaborator, and her husband, sculptor Josef Humplik.

Webern’s 1944-1945 correspondence is strewn with references to bombings, deaths, destruction, privation, and the disintegration of local order; but also noted are the births of several grandchildren. At the age of sixty (i.e., in Dec. 1943), Webern writes that he is living in a barrack away from home and working from 6 am to 5 pm, compelled by the state in a time of war to serve as an air-raid protection police officer. On March 3, 1945 news was relayed to Webern that his only son, Peter, died on February 14 of wounds suffered in a strafing attack on a military train two days earlier.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), Erwin Stein (1885-1958, Austrian musician, pupil and friend of Schoenberg) and Anton Webern (1883-1945).

Death in Allied-https://mahlerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MF-Projects-2.pngistered Austria

On 15 September 1945, returned home during the Allied occupation of Austria, Webern was shot and killed by an American Army soldier following the arrest of his son-in-law for black market activities. This incident occurred when, three-quarters of an hour before a curfew was to have gone into effect, he stepped outside the house so as not to disturb his sleeping grandchildren, in order to enjoy a few draws on a cigar given him that evening by his son-in-law. The soldier responsible for his death was U. S. Army cook Pfc. Raymond Norwood Bell of North Carolina, who was overcome by remorse and died of alcoholism in 1955. Webern was survived by his wife, Wilhelmine Mörtl, who died in 1949, and their three daughters.

Music

Webern’s compositions are concise, distilled, and select; just thirty-one of his compositions were published in his lifetime, and when Pierre Boulez later oversaw a project to record all of his compositions, including some of those without opus numbers, the results fit on just six CDs. Although Webern’s music changed over time, as it often does in the case of long-time composers’ music, it is typified by very spartan textures, in which every note can be clearly heard; carefully chosen timbres, often resulting in very detailed instructions to the performers and use of extended instrumental techniques (flutter tonguing, col legno, and so on); wide-ranging melodic lines, often with leaps greater than an octave; and brevity: the Six Bagatelles for string quartet (1913), for instance, last about three minutes in total.

Webern’s music does not fall into clearly demarcated periods of division because the concerns and techniques of his music were cohesive, interrelated, and only very gradually transformed with the overlap of old and new, particularly in the case of his middle-period lieder. For example, his first use of twelve-tone technique was not especially stylistically significant and only eventually became realized as otherwise so in later works. As such, the divisions employed below are only a convenient simplification.

Formative juvenilia and emergence from study, opp. 1–2, 1899-1908

Webern published little of his early work in particular; like Brahms, though perhaps for not entirely the same reasons, Webern was characteristically meticulous and revised extensively. Many juvenilia remained unknown until the work and findings of the Moldenhauers in the 1960s, effectively obscuring and undermining formative facets of Webern’s musical identity, highly significant even more so in the case of an innovator whose music was crucially marked by rapid stylistic shifts.

Webern’s earliest works consist primarily of lieder, the genre that most belies his roots in Romanticism, specifically German Romanticism; one in which the music yields brief but explicit, potent, and spoken meaning manifested only latently or programmatically in purely instrumental genres; one marked by significant intimacy and lyricism; and one which often associates nature, especially landscapes, with themes of homesickness, solace, wistful yearning, distance, utopia, and belonging. Robert Schumann’s “Mondnacht” is an iconic example; Eichendorff, whose lyric poetry inspired it, is not far removed from the poets (e.g., Richard Dehmel, Gustav Falke, Theodor Storm) whose work inspired Webern and his contemporaries Alban Berg, Max Reger, Arnold Schoenberg, Richard Strauss, Hugo Wolf, and Alexander von Zemlinsky. Wolf’s Mörike-Lieder were especially influential on Webern’s efforts from this period. But well beyond these lieder alone, all of Webern’s music may be said to possess such concerns and qualities, as is evident from his sketches, albeit in an increasingly symbolic, abstract, spare, introverted, and idealized manner. Other works include the orchestral tone poem Im Sommerwind (1904) and the Langsamer Satz (1905) for string quartet.

Anton Webern (1883-1945) and Richard Strauss (1864-1949).

Webern’s first piece after completing his studies with Schoenberg was the Passacaglia for orchestra (1908). Harmonically, it is a step forward into a more advanced language, and the orchestration is somewhat more distinctive than his earlier orchestral work. However, it bears little relation to the fully mature works he is best known for today. One element that is typical is the form itself: the passacaglia is a form which dates back to the 17th century, and a distinguishing feature of Webern’s later work was to be the use of traditional compositional techniques (especially canons) and forms (the Symphony, the Concerto, the String Trio, and String Quartet, and the piano and orchestral Variations) in a modern harmonic and melodic language.

Atonality, lieder, and aphorism, opp. 3–16 and Tot, 1908-1924

For a number of years, Webern wrote pieces which were freely atonal, much in the style of Schoenberg’s early atonal works. Indeed, so in lockstep with Schoenberg was Webern for much of his artistic development that Schoenberg in 1951 wrote that he sometimes no longer knew who he was, Webern had followed so well in his footsteps and shadow, occasionally outdoing or stepping ahead of Schoenberg in execution of Schoenberg’s own or their shared ideas.

There are, however, important cases where Webern may have even more profoundly influenced Schoenberg. Haimo marks the swift, radical influence in 1909 of Webern’s novel and arresting Five Pieces for String Quartet, op. 5, on Schoenberg’s subsequent piano piece op. 11 no. 3; Five Pieces for Orchestra, op. 16; and monodrama Erwartung, op. 17. This shift is distinctly pronounced in a letter Schoenberg wrote to Busoni, which describes a rather Webernian aesthetic: “Harmony is expression and nothing else. […] Away with Pathos! Away with protracted ten-ton scores […]. My music must be brief. Concise! In two notes: not built, but “expressed”!! And the results I wish for: no stylized and sterile protracted emotion. People are not like that: it is impossible for a person to have only one sensation at a time. One has thousands simultaneously. […] And this variegation, this multifariousness, this illogicality which our senses demonstrate, the illogicality presented by their interactions, set forth by some mounting rush of blood, by some reaction of the senses or the nerves, this I should like to have in my music.” In 1949 Schoenberg still remembered being “intoxicated by the enthusiasm of having freed music from the shackles of tonality” and believing with his pupils “that now music could renounce motivic features and remain coherent and comprehensible nonetheless.”

But with opp. 18–20, Schoenberg turned back and revived old techniques, very self-consciously returning to and transforming tradition by the concluding songs of Pierrot lunaire (1912), op. 21, with, e.g., intricately interrelated canons in “Der Mondfleck,” clear waltz rhythms in “Serenade,” a barcarolle (“Heimfahrt”), triadic harmony throughout “O alter Duft.” And in particular, Pierrot was received by Webern as a direction for the composition of his own opp. 14–16, most of all with respect to contrapuntal procedures (and to a lesser degree with respect to the diverse and innovative textural treatment among instruments in increasingly smaller ensembles). “How much I owe to your Pierrot,” he wrote Schoenberg upon completing a setting of George Trakl’s “Abendland III,” op. 14 no. 4, in which, rather unusually for Webern, there is no silence or rest until a pause at the concluding gesture. Indeed, a recurring theme of Webern’s World War I settings is that of the wanderer, estranged or lost and seeking return to or at least retrieval from an earlier time and place; and of some fifty-six songs on which Webern worked 1914–26, he ultimately finished and later published only thirty-two set in order as opp. 12–19. This wartime theme of wandering in search of home ties in with two intricately involved concerns more broadly evident in Webern’s work: first, the death and memory of members of Webern’s family, especially his mother but also including his father and a nephew; and second, Webern’s broad and complex sense of rural and spiritual Heimat. Their importance is marked by Webern’s stage play, Tot (October 1913), which, over the course of six alpine scenes of reflection and self-consolation, draws on Emanuel Swedenborg’s notion of correspondence to relate and to unite the two concerns, the first embodied but otherworldly and the second concrete if increasingly abstracted and idealized.

The similarities between Tot and Webern’s music are striking. In an often programmatic or cinematic fashion Webern ordered his published movements, themselves dramatic or visual tableaux with melodies that frequently begin and end on weak beats or else settle into ostinati or the background. In them, tonality, useful for communicating direction and narrative in programmatic pieces, becomes more tenuous, fragmented, static, symbolic, and visual or spatial in function, thus mirroring the concerns and topics, explicit or implicit, of Webern’s music and his selections for it from the poetry of Stefan George and later Georg Trakl. Webern’s dynamics, orchestration, and timbre are given so as to produce a fragile, intimate, and often novel sound, despite distinctly recalling Mahler, not infrequently bordering on silence at a typical ppp. In some cases, Webern’s choice of instrument in particular functions to represent or to allude to a female voice (e.g., the use of solo violin), to inward or outward luminosity or darkness (e.g., the use of the entire range of register within the ensemble; registral compression and expansion; the use of celesta, harp, and glockenspiel; the use of harmonics and am steg directions), or to angels and heaven (e.g., the use of harp and trumpet in the circling ostinati of op. 6 no. 5 and winding to conclusion at the very end of op. 15 no. 5).

Technical consolidation and formal coherence and expansion, opp. 17–31, 1924-1943

With the Drei Volkstexte (1925), op. 17, Webern used Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique for the first time, and all his subsequent works used this technique. The String Trio (1926–7), op. 20 was both the first purely instrumental work using the twelve tone technique (the other pieces were songs) and the first cast in a traditional musical form. Webern’s music, like that of both Brahms and Schoenberg, is marked by its emphasis on counterpoint and formal considerations; and Webern’s commitment to systematic pitch organization in the twelve-tone method is inseparable from this prior commitment. Webern’s tone rows are often arranged to take advantage of internal symmetries; for example, a twelve-tone row may be divisible into four groups of three pitches which are variations, such as inversions and retrogrades, of each other, thus creating invariance. This gives Webern’s work considerable motivic unity, although this is often obscured by the fragmentation of the melodic lines. This fragmentation occurs through octave displacement (using intervals greater than an octave) and by moving the line rapidly from instrument to instrument in a technique referred to as Klangfarbenmelodie.

Webern’s last pieces seem to indicate another development in style. The two late Cantatas, for example, use larger ensembles than earlier pieces, last longer (No. 1 around nine minutes; No. 2 around sixteen), and are texturally somewhat denser.

Arrangements and orchestrations

In his youth (1903) Webern orchestrated at least five of Franz Schubert’s various lieder, giving the piano accompaniment to an appropriately Schubertian orchestra of strings and pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns: “Der Vollmond Strahlt auf Bergeshöhn” (the Romanze from Rosamunde), “Tränenregen” (from Die schöne Müllerin), “Der Wegweiser” (from Winterreise), “Du bist die Ruh,” and “Ihr Bild”; in 1934, he did the same for Schubert’s six Deutsche Tänze (German Dances) of 1824.

For Schoenberg’s Society for Private Musical Performances in 1921, Webern arranged, among other things, the 1888 Schatz-Walzer (Treasure Waltz) of Johann Strauss II’s Der Zigeunerbaron (The Gypsy Baron) for string quartet, harmonium, and piano.

In 1924 Webern arranged Franz Liszt’s Arbeiterchor (Workers’ Chorus, c. 1847–48) for bass solo, mixed chorus, and large orchestra; it was premièred for the first time in any form on March 13 and 14, 1925, with Webern conducting the first full-length concert of the Austrian Association of Workers Choir. A review in the Amtliche Wiener Zeitung (March 28, 1925) read “neu in jedem Sinne, frisch, unverbraucht, durch ihn zieht die Jugend, die Freude” (“new in every respect, fresh, vital, pervaded by youth and joy”). The text, in English translation, reads in part: “Let us have the adorned spades and scoops,/ Come along all, who wield a sword or pen,/ Come here ye, industrious, brave and strong/ All who create things great or small.” Liszt, initially inspired by his revolutionary countrymen, had left it in manuscript at publisher Carl Haslinger’s discretion.

Performance style

Webern insisted on lyricism, nuance, rubato, sensitivity, and both emotional and intellectual understanding in performance of music; this is evidenced by anecdotes, correspondence, extant recordings of Schubert’s Deutsche Tänze (arr. Webern) and Berg’s Violin Concerto under his direction, many such detailed markings in his scores, and finally by his compositional process as both publicly stated and later revealed in the musical and extramusical metaphors and associations everywhere throughout his sketches. As both a composer and conductor he was one of many (e.g., Wilhelm Furtwängler, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Hermann Scherchen) in a contemporaneous tradition of conscientiously and non-literally handling notated musical figures, phrases, and even entire scores so as to maximize expressivity in performance and to cultivate audience engagement and understanding.

This aspect of Webern’s work had been typically missed in his immediate post-war reception, however, even as it may radically affect the music’s reception. For example, Boulez’s “complete” recording of Webern’s music yielded more to this aesthetic the second time after largely missing it the first; but Eliahu Inbal’s rendition of Webern’s symphony with the hr-Sinfonieorchester is still far more within the spirit of the late Romantic performance tradition (which Webern seemingly intended for his music), nearly slowing to half-tempo for the whole of first movement and taking care to delineate and shape each melodic strand and expressive gesture throughout the entirety of the work. Günter Wand’s 1966 recording of the Cantata No. 1 (1938–40), op. 29, with the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks et al., may likewise be contrasted with both of Boulez’s renditions.

Legacy

Webern’s music started to spark some interest in the 1920s. By the mid-1940s, they were having a decisive effect on John Cage. However, Webern mostly remained the most obscure and arcane composer of the Second Viennese School in his lifetime. After World War II, interest in Webern increased, and his œuvre acquired what Alex Ross calls “a saintly, visionary aura.” When Webern’s Piano Variations were performed at Darmstadt in 1948, young composers listened in a quasi-religious trance.

Meanwhile, Webern’s characteristically passionate pan-German nationalism and censurable, sordid political sympathies, however naive or delusional, were not widely known or went unmentioned; perhaps in some parts due to his personal and political associations before, his degradation, mistreatment and disillusionment during, and then his fate immediately after the German Reich. Significantly as relates to his reception, Webern never compromised his artistic identity and values, as Stravinsky was later to note.

In 1955, the second issue of Eimert and Stockhausen’s journal Die Reihe was devoted to Webern’s œuvre, and in 1960 his lectures were published by Universal Edition (UE) music publishers. It has been suggested that the serialists’ fascination with Webern’s works came not for their audible content, but rather from the transparency of their scores, which made their musical analysis easier. One of the founders of European post-Webern serialism, Karel Goeyvaerts, wrote: “[the impression of the first time I heard Webern’s music in a concert performance] was the same as I was to experience a few years later when I first laid eyes on a Mondriaan canvas…: those things, of which I had acquired an extremely intimate knowledge, came across as crude and unfinished when seen in reality.”

Webern’s work was a seminal influence on that of Andreae Szervánszky; thus György Kurtág mimics and quotes both Webern and Szervánszky himself variously throughout his own Officium Breve in memoriam Andreae Szervánszky for string quartet, op. 28 (1988–89).