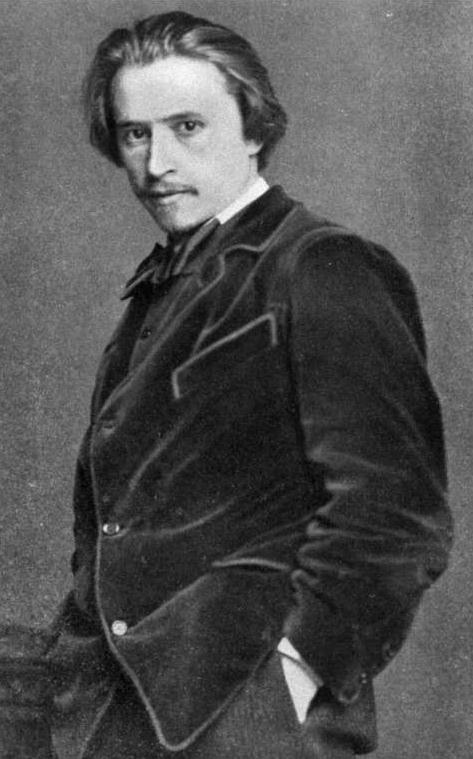

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) in 1910.

- Profession: Composer.

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler: Friend, Pernerstorfer Circle (member). Fellow student at the Conservatory of Vienna

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 13-03-1860 Windischgrätz, Slovenia.

- Died: 22-02-1903 Vienna, Austria.

- Buried: 24-02-1903 Central cemetery, Vienna, Austria. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) attended at funeral. Grave 32A-10.

Hugo Wolf was an Austrian composer of Slovene origin, particularly noted for his art songs, or Lieder. He brought to this form a concentrated expressive intensity which was unique in late Romantic music, somewhat related to that of the Second Viennese School in concision but diverging greatly in technique. Though he had several bursts of extraordinary productivity, particularly in 1888 and 1889, depression frequently interrupted his creative periods, and his last composition was written in 1898, before he suffered a mental collapse caused by syphilis.

Hugo Wolf was born in Windischgrätz (now Slovenj Gradec, Slovenia), then a part of the Austrian Empire. From his maternal side, he was related to Herbert von Karajan. He spent most of his life in Vienna, becoming a representative of “New German” trend in Lieder, a trend which followed from the expressive, chromatic and dramatic musical innovations of Richard Wagner.

A child prodigy, Wolf was taught piano and violin by his father beginning at the age of four, and once in primary school studied piano and music theory with Sebastian Weixler. Subjects other than music failed to hold his interest; he was dismissed from the first secondary school he attended as being “wholly inadequate,” left another over his difficulties in the compulsory Latin studies, and after a falling-out with a professor who commented on his “damned music,”quit the last.

From there, he went to the Vienna Conservatory much to his father’s disappointment, who had hoped his son would not try to make his living from music. Once again, however, he was dismissed for “breach of discipline,” although the oft-rebellious Wolf would claim he quit in frustration over the school’s conservatism.

After eight months with his family, he returned to Vienna to teach music. Though his fiery temperament was not ideally suited to teaching, Wolf’s musical gifts, as well as his personal charm, earned him attention and patronage. Support of benefactors allowed him to make a living as a composer, and a daughter of one of his greatest benefactors inspired him to write, Vally (“Valentine”) Franck, his first love, with whom he was involved for three years.

During their relationship, hints of his mature style would become evident in his Lieder. Wolf was prone to depression and wide mood swings, which would affect him all through his life. When Franck left him just before his 21st birthday, he was despondent. He returned home, although his family relationships were also strained; his father was still convinced his son was a ne’er-do-well. His brief and undistinguished tenure as second Kapellmeister at Salzburg only reinforced this opinion: Wolf had neither the temperament, the conducting technique nor the affinity for the decidedly non-Wagnerian repertoire to be successful, and within a year had again returned to Vienna to teach in much the same circumstances as before.

Wagner’s death in February 1883 was another deeply moving event in the life of the young composer. The song “Zur Ruh, zur Ruh” was composed shortly afterward and is considered to be the best of his early works; it is speculated that it was intended as an elegy for Wagner. Wolf often despaired of his own future in the ensuing years, in a world from which his idol had departed, leaving tremendous footsteps to follow and no guidance on how to do so. This left him often extremely temperamental, alienating friends and patrons, although his charm helped him retain them more than his actions merited.

His songs had meanwhile caught the attention of Franz Liszt, whom he respected greatly, and who like Wolf’s previous mentors advised him to pursue larger forms; advice he this time followed with the symphonic tone poem Penthesilea. His activities as a critic began to pick up. He was merciless in his criticism of the inferior works he saw taking over the musical atmosphere of the time; those of Anton Rubinstein he considered particularly odious. But he was as fervent in his support of Liszt, Schubert and Chopin, whose genius he recognized. Known as “Wild Wolf” for the intensity and expressive strength of his convictions, his vitriol made him some enemies.

He composed little during this time, and what he did write he couldn’t get performed; the Rosé Quartet (led by Vienna Philharmonic concertmaster Arnold Rosé) would not even look at his D minor Quartet after it was picked apart in a column, and the premiere of Penthesilea was met by the Vienna Philharmonic, when they tried it out under their celebrated conservative conductor Hans Richter, with nothing but derision for ‘the man who had dared to criticize “Meister Brahms,'” as Richter himself caustically put it.

He abandoned his activities as a critic in 1887 and began composing once more; perhaps not unexpectedly, the first songs he wrote after his compositional hiatus (to poems by Goethe, Joseph von Eichendorff and Joseph Viktor von Scheffel) emphasized themes of strength and resolution under adversity. Shortly thereafter, he completed the terse, witty one-movement Italian Serenade for string quartet which is regarded as one of the finest examples of his mature instrumental compositional style. Only a week later his father died, leaving him devastated, and he did not compose for the remainder of the year.

Maturity (1888-1896)

1888 and 1889 proved to be amazingly productive years for Wolf, and a turning point in his career. After the publication of a dozen of his songs late the preceding year, Wolf once again desired to return to composing, and travelled to the vacation home of the Werners—family friends whom Wolf had known since childhood—in Perchtoldsdorf (a short train ride from Vienna), to escape and compose in solitude. Here he composed the Mörike-Lieder at a frenzied pace. A short break, and a change of house, this time to the vacation home of more longtime friends, Frederick Eckstein (1861-1939) family, and the Eichendorff-Lieder followed, then the 51 Goethe-Lieder, spilling into 1889. After a summer holiday, the Spanisches Liederbuch was begun in October 1889; though Spanish-flavoured compositions were in fashion in the day, Wolf sought out poems that had been neglected by other composers.

Wolf himself saw the merit of these compositions immediately, raving to friends that they were the best things he had yet composed (it was with the aid and urging of several of the more influential of them that the works were initially published). It was now that the world outside Vienna would recognize Wolf as well. Tenor Ferdinand Jäger, whom Wolf had heard in Parsifal during his brief summer break from composing, was present at one of the first concerts of the Mörike works and quickly became a champion of his music, performing a recital of only Wolf and Beethoven in December 1888.

His works were praised in reviews, including one in the Münchener Allgemeine Zeitung, a widely read German newspaper. (The recognition was not always positive; Brahms’s adherents, still smarting from Wolf’s merciless reviews, returned the favor-when they would have anything to do with him at all. Brahms’s biographer Max Kalbeck ridiculed Wolf for his immature writing and odd tonalities; another composer refused to share a program with him, while Amalie Materna, a Wagnerian singer, had to cancel her Wolf recital when allegedly faced with the threat of being on the critics’ blacklist if she went on.)

Only a few more settings, completing the first half of the Italienisches Liederbuch, were composed in 1891 before Wolf’s mental and physical health once again took a downturn at the end of the year; exhaustion from his prolific past few years combined with the effects of syphilis and his depressive temperament caused him to stop composing for the next several years. Continuing concerts of his works in Austria and Germany spread his growing fame; even Brahms and the critics who had previously reviled Wolf gave favorable reviews. However, Wolf was consumed with depression, which stopped him from writing—which only left him more depressed. He completed orchestrations of previous works, but new compositions were not forthcoming, and certainly not the opera which he was now fixated on composing, still convinced that success in the larger forms was the mark of compositional greatness.

Wolf had scornfully rejected the libretto to Der Corregidor when it was first presented to him in 1890, but his determination to compose an opera blinded him to its faults upon second glance. Based on The Three-Cornered Hat, by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón, the darkly humorous story about an adulterous love triangle is one that Wolf could identify with: he had been in love with Melanie Köchert, married to his friend Heinrich Köchert, for several years. (It is speculated that their romance began in earnest in 1884, when Wolf accompanied the Köcherts on holiday; though Heinrich discovered the affair in 1893 he remained Wolf’s patron and Melanie’s husband.) The opera was completed in nine months and was initially met with success, but Wolf’s musical setting could not compensate for the weakness of the text, and it was doomed to failure; it has not yet been successfully revived.

A renewal of creative activity resulted in Wolf’s completion of the Italienisches Liederbuch with two dozen songs written in March and April of 1896, the composition of three Michelangelo Lieder in March, 1897 (a group of six had been projected) and preliminary work during that year on an opera, Manuel Venegas.

Final years (1897-1903)

Wolf’s last concert appearance, which included his early champion Jäger, was in February 1897. Shortly thereafter Wolf slipped into syphilitic insanity, with only occasional spells of wellbeing. He left sixty pages of an unfinished opera, Manuel Venegas, in 1897, in a desperate attempt to finish before he lost his mind completely; after mid-1899 he could make no music at all and once even tried to drown himself, after which he was placed in a Vienna asylum at his own insistence. Melanie visited him faithfully during his decline until his death on 22 February 1903, but her unfaithfulness to her husband tortured her and she killed herself in 1906.

Music

Wolf’s greatest musical influence was Richard Wagner, who, in an encounter after Wolf first came to the Vienna Conservatory, encouraged the young composer to persist in composing and to attempt larger-scale works, cementing Wolf’s desire to emulate his musical idol. His antipathy to Johannes Brahms was fueled equally by his devotion to Wagner’s musical radicalism and his loathing of Brahms’ musical conservatism.

He is best known by his lieder, his temperament and inclination leading him to more intimate, subjective and terse musical utterances. Although he initially believed that mastering the larger forms was the hallmark of a great composer (a belief his early mentors reinforced), the smaller scale of the art song proved to provide an ideal creative outlet for his musical expression and came to be regarded as the genre best suited to his peculiar genius. Wolf’s lieder are noted for compressing expansive musical ideas and depth of feeling, fed by his skill at finding the just right musical setting for the poetry that inspired him .

Though Wolf himself was obsessed with the idea that to compose only short forms was to be second-rate, his organization of lyrics of particular poets (Goethe; Mörike; Eichendorff; Heyse & Geibel in the Spanish and Italian Songbooks) into semicyclical anthologies, finding connections between texts not explicitly intended by the poets he set and his conceptions of individual songs as dramatic works in miniature, mark him as a talented dramatist despite having written only one not particularly successful opera, Der Corregidor.

Early in his career Wolf modelled his lieder after those of Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann, particularly in the period around his relationship with Vally Franck; in fact, they were good enough imitations to pass off as the real thing, which he once attempted, though his cover was blown too soon. It is speculated that his choice of lieder texts in the earlier years, largely dealing with sin and anguish, were partly influenced by his contraction of syphilis. His love for Vally, not fully requited, inspired highly chromatic and philosophical lieder that could be regarded as successors to Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder cycle. Others were as distant from those in mood as possible; lighthearted and humorous. The rarely heard symphonic poem Penthesilea is tempestuous and highly colored as well. Although Wolf admired Liszt, who had encouraged him to complete the work, he felt Liszt’s own music too dry and academic and strove for color and passion.

1888 marked a turning point in his style as well as his career, with the Mörike, Eichendorff and Goethe sets drawing him away from Schubert’s simpler, more diatonic lyricism and into “Wölferl’s own howl”. Mörike in particular drew out and complemented Wolf’s musical gifts, the variety of subjects suiting Wolf’s tailoring of music to text, his dark sense of humor matching Wolf’s own, his insight and imagery demanding a wider variety of compositional techniques and command of text painting to portray. In his later works he relied less on the text to give him his musical framework and more on his pure musical ideas themselves; the later Spanish and Italian songs reflect this move toward “absolute music”.

Wolf wrote hundreds of lieder, three operas, incidental music, choral music, as well as some rarely heard orchestral, chamber and piano music. His most famous instrumental piece is the Italian Serenade (1887), originally for string quartet and later transcribed for orchestra, which marked the beginning of his mature style.

Wolf was famous for his use of tonality to reinforce meaning. Concentrating on two tonal areas to musically depict ambiguity and conflict in the text became a hallmark of his style, resolving only when appropriate to the meaning of the song. His chosen texts were often full of anguish and inability to find resolution, and thus so too was the tonality wandering, unable to return to the home key. Use of deceptive cadences, chromaticism, dissonance, and chromatic mediants obscure the harmonic destination for as long as the psychological tension is sustained. His formal structure as well reflected the texts being set, and he wrote almost none of the straightforward strophic songs favoured by his contemporaries, instead building the form around the nature of the work.