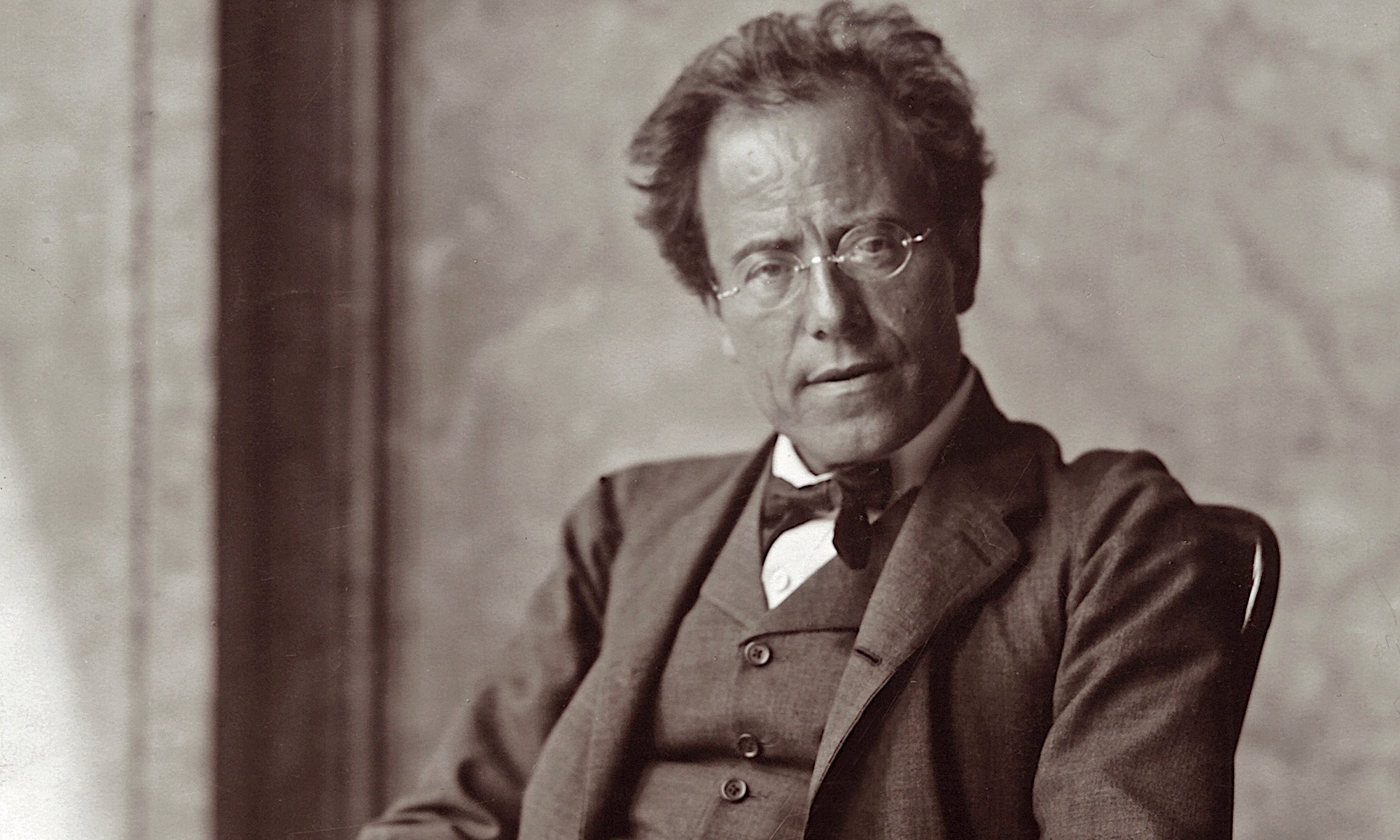

- Profession: Critic Neue Freie Presse, professor University of Vienna.

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler: Influential critic, pro Brahms, anti Wagner and Bruckner.

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 11-09-1825 Prague, Czech Republic.

- Died: 06-08-1904 Baden, Austria. Aged 78.

- Buried: 09-08-1904 Central cemetery, Vienna, Austria. Grave 18-1-9. With Sofie Hanslick, aged 88.

Eduard Hanslick was a German Bohemian music critic. He was born in Prague (then in the Austrian Empire), the son of Joseph Adolph Hanslik, a bibliographer and music teacher from a German-speaking family, and one of his piano pupils, the daughter of a Jewish merchant from Vienna. At the age of eighteen Hanslick went to study music with Václav Tomášek, one of Prague’s renowned musicians. He also studied law at Prague University and obtained a degree in that field, but his amateur study of music eventually led to writing music reviews for small town newspapers, then the Wiener Musik-Zeitung and eventually the Neue Freie Presse, where he was music critic until retirement.

Whilst still a student, in 1845, he met with Richard Wagner in Marienbad; the composer, noting the young man’s enthusiasm, invited him to Dresden to hear his opera Tannhäuser; here Hanslick also met with Robert Schumann.

In 1854 he published his influential book On the Beautiful in Music. By this time his interest in Wagner had begun to cool; he had written a disparaging review of the first Vienna production of Lohengrin. From this point on, Hanslick found his sympathies moving away from the so-called ‘music of the Future’ associated with Wagner and Franz Liszt, and more towards music he conceived as directly descending from the traditions of Mozart, Beethoven and Schumann — in particular the music of Johannes Brahms (who dedicated to him his set of waltzes opus 39 for piano duet).

In 1869, in a revised edition of his essay Jewishness in Music, Wagner attacked Hanslick as ‘of gracefully concealed Jewish origin’, and asserted that his Jewish style of criticism was anti-German. It is sometimes claimed that Wagner caricatured Hanslick in his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as the carping critic Beckmesser (whose name was originally to be Veit Hanslich).

Hanslick’s unpaid lectureship at the University of Vienna led in 1870 to a full professorship in history and aesthetic of music and later to a doctorate honoris causa. Hanslick often served on juries for musical competitions and held a post at the Austrian Ministry of Culture and fulfilled other https://mahlerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MF-Projects-2.pngistrative roles. He retired after writing his memoirs, but still wrote articles on the most important premieres of the day, up to his death in 1904 in Baden.

Hanslick’s tastes were conservative; in his memoirs he said that for him musical history really began with Mozart and culminated in Beethoven, Schumann and Brahms. He is best remembered today for his critical advocacy of Brahms as against the school of Wagner, an episode in 19th century music history sometimes called the War of the Romantics. The critic Richard Pohl, of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, represented the progressive composers of the “Music of the Future”.

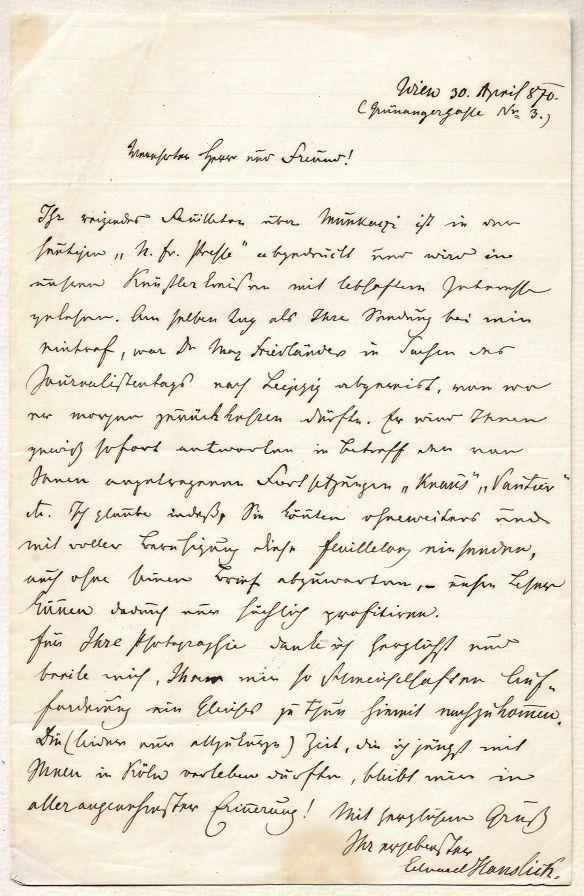

30-04-1870. Letter by Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904). “Verehrter Herr uund Freund! Ihr reizender Feuilleton über (…) ist in der heutigen “N(euen) fr(eien) Presse” abgedruckt und wird in unsern Künstlerkreisen mit lebhaften Interesse gelesen. Am selben Tag als Ihre Sendung bei mir eintraf, war Dr. Max Friedländer in Sachen des Journalistentags nach Leipzig abgereist, von wo er morgen zurückkehren dürfte”. Copyright: Bert and Judith van der Waal van Dijk (cbjvdwvd).

Being a close friend of Brahms from 1862, Hanslick possibly had some influence on Brahms’s composing, often getting to hear new music before it was published. Hanslick saw Wagner’s reliance on dramatics and word painting as inimical to the nature of music, which he thought to be expressive solely by virtue of its form, and not through any extra-musical associations. On the other hand, he referred to extra-musicality when he asked, “When you play Chopin’s mazurkas, do you not feel the mournful and oppressive air of the Battle of Ostroleka (1831)? (Hanslick 1848, p. 157).

The theoretical framework of Hanslick’s criticism is expounded in his book of 1854, Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Beautiful in Music), which started as an attack on the Wagnerian aesthetic and established itself as an influential text, subsequently going through many editions and translations in several languages. Other targets for Hanslick’s heavy criticism were Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf. Of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, he accused composer and soloist Adolph Brodsky of putting the audience “through hell” with music “which stinks to the ear”; he was also lukewarm towards the same composer’s Sixth Symphony.

Hanslick is noted as one of the first widely influential music critics. While his aesthetics and his criticism are typically considered separately, they are importantly connected. Hanslick was an outspoken opponent of the music of Liszt and Wagner, which broke down traditional musical forms as a means of communicating something extra-musical. His opposition to “the music of the future” is congruent with his aesthetics of music: the meaning of music is the form of music. It is along these lines that Hanslick became one of Brahms’s champions and often pitted him against Wagner. For this reason, Brahms is often mistakenly positioned as being anti-Wagnerian himself, a historical interpretation that disregards Brahms’s and Wagner’s mutual admiration for each other.