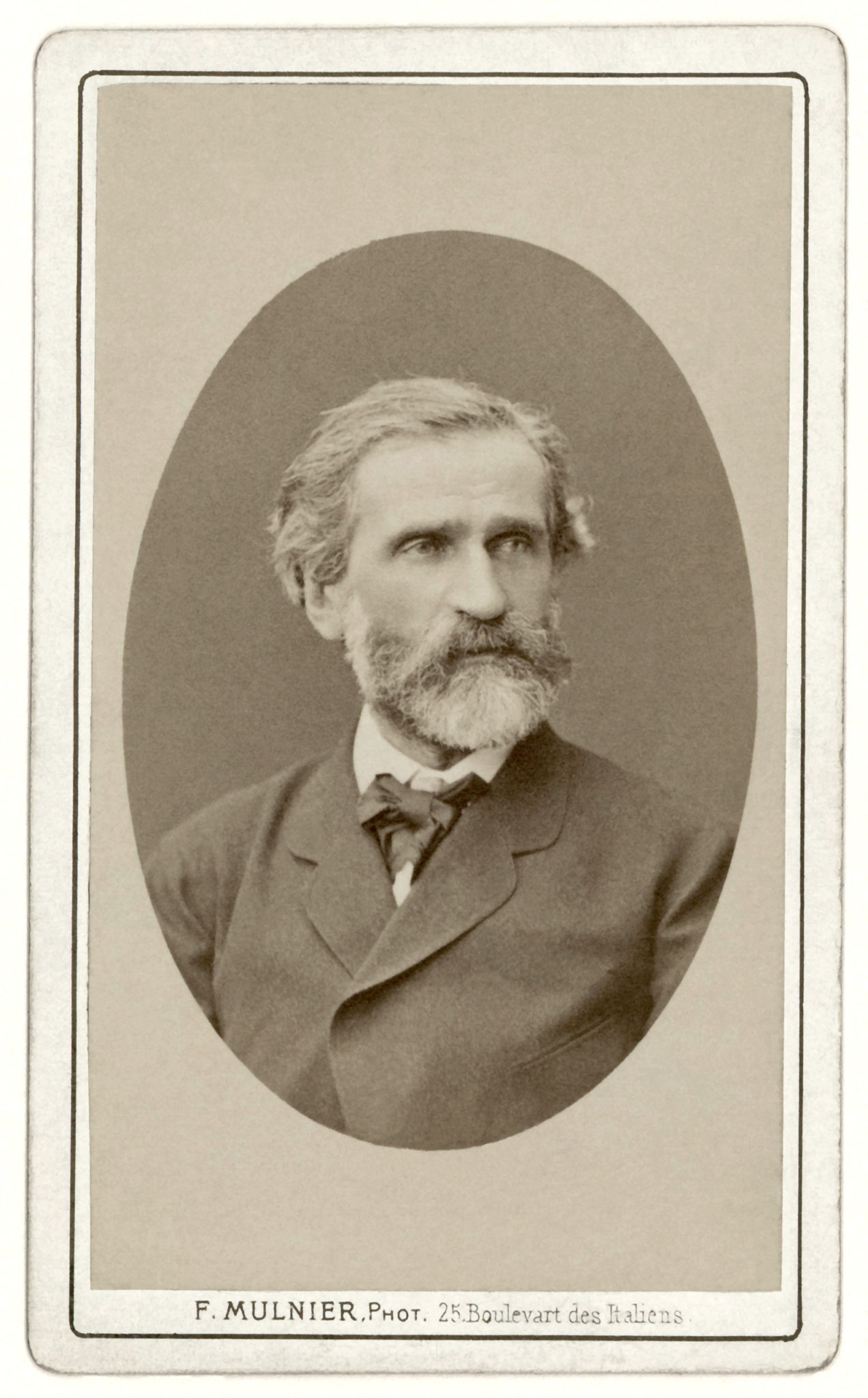

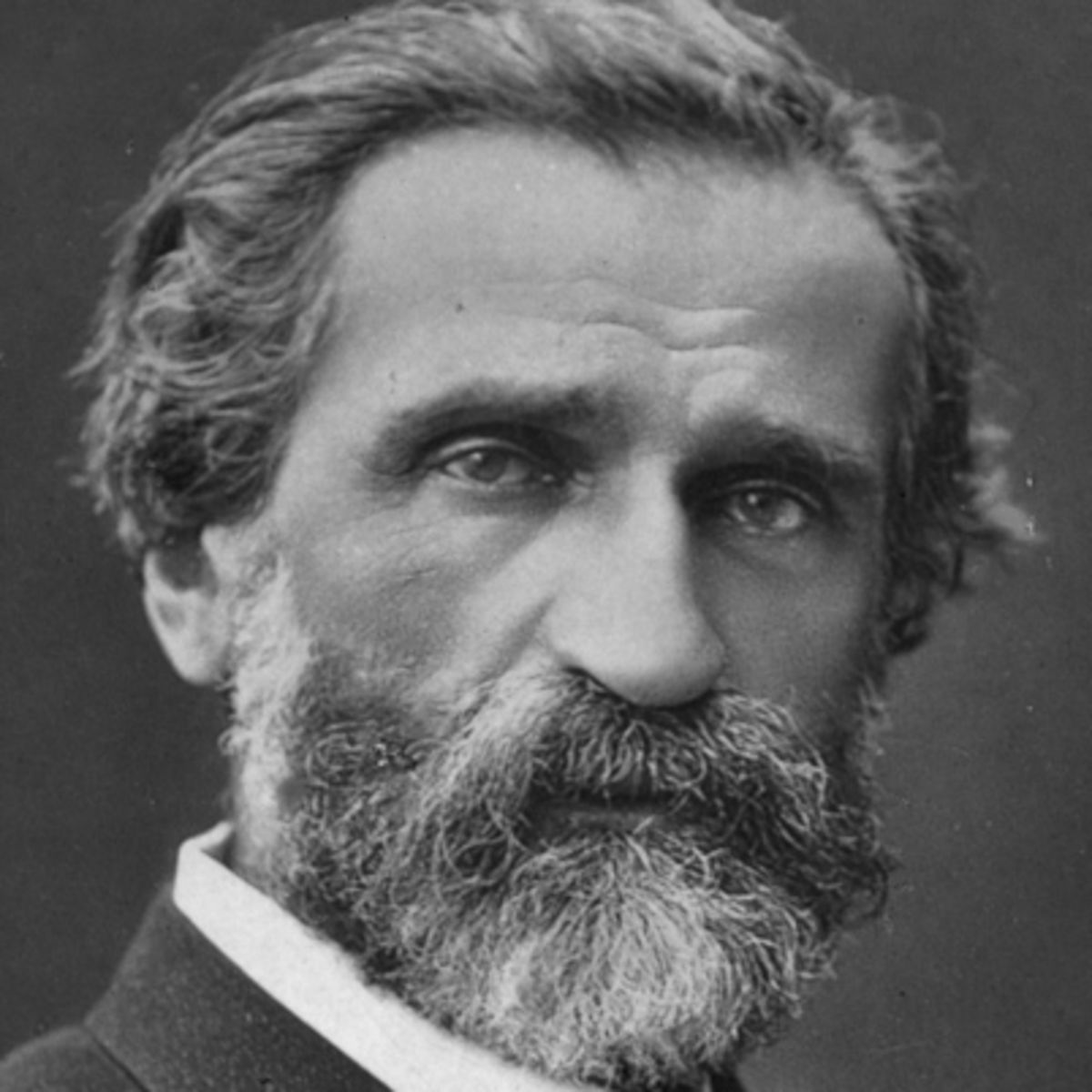

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813-1901).

- Profession: Composer.

- Residences: Italy.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 10-10-1813 Le Ronole (Parma), Italy.

- Died: 27-01-1901 Milan, Italy.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Verdi was initially buried in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale. A month later, his body was moved to the “crypt” of the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, a rest home for retired musicians that Verdi had recently established.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi was an Italian Romantic composer primarily known for his operas. He is considered, with Richard Wagner, the preëminent opera composer of the 19th century. Verdi dominated the Italian opera scene after the eras of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini. His works are frequently performed in opera houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root in popular culture, examples being “La donna è mobile” from Rigoletto, “Libiamo ne’ lieti calici” (The Drinking Song) from La traviata, “Va, pensiero” (The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, the “Coro di zingari” (Anvil Chorus) from Il trovatore and the “Grand March” from Aida.

Moved by the death of compatriot Alessandro Manzoni, Verdi wrote Messa da Requiem in 1874 in Manzoni’s honour, a work now regarded as a masterpiece of the oratorio tradition and a testimony to his capacity outside the field of opera. Visionary and politically engaged, he remains – alongside Garibaldi and Cavour – an emblematic figure of the reunification process (the Risorgimento) of the Italian Peninsula.

The early years: Le Roncole, Busseto and Milan

Verdi was born the son of Carlo Giuseppe Verdi (1785–1867) and Luigia Uttini (1787–1851) in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro and within the borders of the First French Empire after the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813-1901).

The baptismal register, prepared on 11 October, lists his parents Carlo and Luigia as “innkeeper” and “spinner” respectively. Additionally, it lists Verdi as being “born yesterday”, but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October. Today, his birthday is celebrated on 10 October, as certainly was the case of the bi-centennial in 2013. The next day, he was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church in Latin as Joseph Fortuninus Franciscus. The day after that (Tuesday), Verdi’s father took his newborn the three miles to Busseto, where the baby was recorded as Joseph Fortunin François, the clerk writing in French. As biographer George Martin notes, “so it happened, that for the civil and temporal world, Verdi was born a Frenchman.”

When Verdi was almost three, his parents had a baby girl, Giuseppa. However she died in 1833. From the age of four, Verdi was given private lessons in Latin and Italian by the village schoolmaster, Baistrocchi, and at 6 he attended the local school. At the same time, it appears that he began to learn to play the organ, becoming more and more attracted to music that his parents finally provided him with a spinet. As one of the composer’s significant biographers, Mary Jane Phillips-Matz notes, “Verdi’s gift for music was apparent by then, even by 1820 or 1821. This period also began his association with the local church, serving in the choir, being an altar boy for a while, and taken organ lessons. After schoolmaster Baistrocchi’s death, Verdi became the official paid organist at the age of eight.

1820 to 1832: Musical education in Busseto

In regard to Verdi’s family background, musicologist Roger Parker points out that both of Verdi’s parents “belonged to families of small landowners and traders, certainly not the illiterate peasants from which Verdi later liked to present himself as having emerged.” Also, during this time, “Carlo Verdi was energetic in furthering his son’s education…something which Verdi tended to hide in later life,” and, later, Parker states that, during these early years in Busseto, “The picture emerges of youthful precocity eagerly nurtured by an ambitious father and of a sustained, sophisticated and elaborate formal education [but about which, later in life, Verdi would give] the impression of [having] a largely self-taught and obscure youth.”

In 1823, when he was 10, Verdi’s parents arranged for the boy to attend school in Busseto, enrolling him in a Ginnasio—an upper school for boys—run by Don Pietro Seletti. He was looked after by Pietro Michiara and his musical family, while the parents remained in charge of the inn at Le Roncole. However, Verdi returned regularly to play the organ on Sundays, walking the several kilometres. In Busseto, the future composer’s education was greatly facilitated by visits to the large town library with its 10,000 volumes. At age 11 he began to train in Italian, Latin, the humanities, and rhetoric. By the time he was 12, Verdi began lessons with Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella at San Bartolomeo, director of the municipal music school and co-director of the local Società Filarmonica (Philharmonic Society).

It was with Provesi that Verdi was given his first lessons in composition and, beginning a year or two later, he was to write that “From the ages of 13 to 18 I wrote a motley assortment of pieces: marches for band by the hundred, perhaps as many little sinfonie that were used in church, in the theatre and at concerts, five or six concertos and sets of variations for pianoforte, which I played myself at concerts, many serenades, cantatas (arias, duets, very many trios) and various pieces of church music, of which I remember only a Stabat Mater”.

The other director of the Philharmonic Society was Antonio Barezzi (it), a 29-year-old wholesale grocer and distiller, who was described by a contemporary as a “manic dilettante” when it came to music [and who], as Phillips-Matz notes, “had mastered several instruments, among them the flute, clarinet, and ophicleide”. A regular member of the Philharmonic orchestra, Barezzi invited members to the spacious salon of his townhouse where they held rehearsals and performances. During those years, the Busseto Philharmonic was composed of 38 musicians, a considerable number of whom had been playing for over 15 years. They could also draw upon four tenors, two basses, a soprano or two, plus a full chorus.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813-1901).

The young Verdi did not immediately become involved with the Philharmonic, so arduous were his other duties and the broad range of his studies. This resulted in some conflicts with his two principal teachers—Provesi for music and the priest Seletti at the Ginassio where he focused on academic studies, but by June 1827, he had completed the academic work, graduating with honours. After that time, he was able to focus solely on music under Provesi until June 1829. Fortuitously, when Verdi was 13, he was asked to step in as a replacement to play in what became his first public event in the town; he was an immediate success largely playing his own music to the surprise of many and it gave him immediate recognition in his home town.

By 1829/30, Verdi had established himself as a major force in the Philharmonic: “no one of us could rival him” reported the Secretary of the organisation, Giuseppe Demald? who was Barezzi’s first cousin. His account of those times, Ceni biografici del Maestro Verdi appears in Phillips-Matz’s biography. Additionally, these years saw Verdi develop a lifelong interest in the writings of William Shakespeare (several of whose works he made into operas from 1847 forward); of Alessandro Manzoni whose I promesi sposi—a major work of Italian fiction—had a significant impact on the 16-year-old Verdi when he read it; and, thirdly, of the dramatist Vittorio Alfieri. Verdi would name his children Virginia and Icilio Romano after characters in Alfieri’s tragedy Virginia.

It was Alfieri’s drama, Saul, which Verdi used as the basis of an eight-movement cantata called I deliri di Saul written at age 15 and performed in Bergamo to great acclaim, Demaldè noting: “The composition is a real jewel, a precious stone..” and Barezzi stating that it was “the first work of some significance…in which he shows a vivid imagination, a philosophical outlook, and sound judgment in the arrangement of instrumental parts”.

In late 1829, it become clear that Verdi needed to expand his musical horizons with either employment in some aspect of music or in further study. He had completed his studies with Provesi, who declared that he had no more to teach him, he was turned down for a local church organist’s post, and he was planning to return to Le Roncole. It was at that point that Barezzi intervened, declaring “You are born for something better than that”.

The young man’s increasingly close connection to the Barezzi family household had one other consequence. Born a few months before Verdi, the Barezzi’s eldest daughter, Margherita, was becoming an accomplished singer and her father was beginning to look for opportunities for her to study in Milan. Verdi had been giving singing and piano lessons to Margherita and they spent time together playing and talking about music. But by 1830, Margherita’s mother discovered that the young couple were in love. That further determined Antonio to have his daughter move away.

At the same time, Carlo Verdi, whose family business was in deep trouble, was exploring possibilities for his son to study music, and he made an application for funding to the Monte di Pietà e d’Abbondanza in Busseto, backed by strong references from Provesi and others. Verdi was invited to stay in the Barezzi household and settled in, continuing to help the Philharmonic with copying scores and all manner of related chores while all awaited news of the Pietà scholarship.

1832 to 1834: Musical education in Milan

Verdi set his sights on Milan, then the cultural capital of northern Italy but, when the successful outcome of his application to the Monte di Pietà e d’Abbondanza was announced, he learned that he would have to wait until 1833 until funds were available. Fortunately, Barezzi recognized and wished to encourage the young man’s talent and he guaranteed initial financial support for a year. Verdi, 18, set out for Milan in June 1832 accompanied by his father and Provesi.

In Milan, where he stayed at the home of his former teacher, Seletti, he applied to study at the Conservatory, but after waiting for several days, he was rejected on several grounds. The Conservatory’s reasoning was based on his limited piano technique (considered crucial by one teacher), his not being a resident of the Lombardy/Venetia region, and that he was older than the normal age to begin study there. Seletti wrote to Barezzi with the news and urging him to come to Milan, but Barezzi made arrangements for the young man to become a private pupil of Vincenzo Lavigna, paid for by him. Lavigna had been maestro concertatore at La Scala and he gave lessons in counterpoint along with a broader range of musical studies, with Verdi’s classes beginning in July and his teacher describing his compositions as “very promising.” Verdi began attending operatic performances and concerts.

A year passed before the young man returned briefly to Busetto. News came of Provesi’s death and Verdi’s attitude towards his studies seemed to change as he enjoyed city life. He frequently attended La Scala and, for example during the 1834-35 season, he would have been able to see Giuditta Pasta as Norma and Maria Malibran in Rossini’s Otello and La sonnambula among others, as well as works by Luigi Ricci, Gaetano Donizetti, and Saverio Mercadante. Also, it was during this period that he attended the Salotto Maffei, Countess Clara Maffei’s salons in Milan. Verdi became a lifelong friend and correspondent.

Italian opera composers active in the primo ottocento and influential on Verdi and his music: (clockwise from lower left) Gioachino Rossini (retired after 1829); Vincenzo Bellini (died in 1835); Luigi Ricci; Saverio Mercadante; Gaetano Donizetti, all still active in Verdi’s early years

During his student days in Milan, Verdi had begun making connections in the world of music that were to stand him in good stead. As the composer told it—48 years later—in his 1879 An Autobiographical Sketch written at Sant’Agata, these connections included an introduction by Lavigna to an amateur choral group, the Società Filarmonica, led by Pietro Massini, a man whom he described as: “if not very learned, was at least tenacious and patient: therefore just what was needed for a society of amateurs. They were organizing at the Teatro Filodrammatico the performance of an oratorio by Haydn, The Creation, [and] my teacher Lavigna asked me if, for my instruction, I wanted to follow the rehearsals, and I accepted with pleasure.”

Attending the Società frequently in 1834, Verdi soon found himself functioning as rehearsal director and continuo player for The Creation when, in the absence of all three rehearsal conductors, Massini asked Verdi to accompany a rehearsal, which he did with success. Verdi goes on to explain how Massini “proposed that I write an opera for the Teatro Filodrammatico….He sent me a libretto, which after being revised by Solera, became Oberto, Conte di Bonifacio”.

Returning briefly to Milan from Busseto in 1836, he conducted Rossini’s La cenerentola but many steps had to be taken before Oberto became a reality on the opera stage. In his 1879 “Sketch”, Verdi supplied the anecdotes of how his first opera came about, but before that could begin to happen, he returned to Busseto for two-and-a-half years.

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813-1901).

1834 to 1839: Return to Busseto

Carlo Verdi came to Milan to take the young man back home in mid-1834, saying he had to be in Busseto for the decision about who would succeed Provesi. However, rival factions in the town campaigned against him, and Verdi did not get the post. Later, however—with Barezzi’s help—he did obtain the secular post of maestro di musica. He taught, gave lessons, and conducted the Philharmonic for several months before returning to Milan in early 1835. In Milan, Barezzi again supported him, lodging him in an apartment with another of his protégés, Luigi Martelli. Verdi was expected to teach Martelli and continue to take lessons from Lavigna so he would become formally qualified for a teaching post. By July 1835, he obtained his certification from Lavigna, who stated that “I therefore believe him to be ready to practice his profession at the level of maestro di cappella.”

Back in Busseto, in 1835, the post of director of the music school remained unfilled. Verdi became its director with a three year contract. He married Margherita in May 1836, and by March 1837, she had given birth to their first child, Virginia Maria Luigia on 26 March 1837. Icilio Romano followed on 11 July 1838, but both died while Verdi was working on his first and second operas, Virginia on 12 August 1838 while the couple was still in Busseto and Ilicio on 22 October 1839 after the couple returned to Milan in February 1839.

Verdi took advantage of his connection to Pietro Massini, informing him in a series of letters from 1835 to 1837 about his progress in writing his first opera using Massini’s libretto based on a work by Antonio Piazza, a Milanese “journalist and man of letters.” By then it had been given the title of Rocester and the young composer expressed hopes of a production at the Teatro Ducale in Parma with professional singers. Only when he encountered difficulties with that idea—the company appearing uninterested in a new work by an unknown composer—did he return to Massini in Milan. In subsequent letters, he continues to ask for Massini’s assistance to stage the opera in Milan.

Last years

On 29 July 1900, King Umberto I of Italy was assassinated by Gaetano Bresci, a deed that horrified the aged composer. While staying at the Grand Hotel et de Milan in Milan, Verdi suffered a stroke on 21 January 1901. He gradually grew more feeble and died nearly a week later, on 27 January. Arturo Toscanini conducted the vast forces of combined orchestras and choirs composed of musicians from throughout Italy at Verdi’s funeral service in Milan. To date, it remains the largest public assembly of any event in the history of Italy. Verdi was initially buried in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale. A month later, his body was moved to the “crypt” of the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, a rest home for retired musicians that Verdi had recently established.