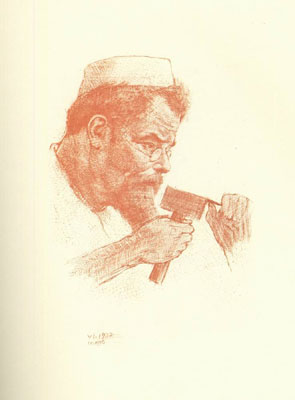

Max Klinger (1857-1920). Portrait by Emil Orlik (1870-1932), 1902.

- Profession: Sculpter, painter.

- Residences: Leipzig, Karsruhe.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 18-02-1857 Leipzig, Germany.

- Died: 05-07-1920, Grossjena, Naumburg (Saale), Germany.

- Buried: 08-07-1920 Weinberg, Naumburg (Saale) Germany.

Max Klinger was a German Symbolist painter, sculptor, printmaker, and writer. Klinger was born in Leipzig and studied in Karlsruhe. An admirer of the etchings of Menzel and Goya, he shortly became a skilled and imaginative engraver in his own right. He began creating sculptures in the early 1880s. From 1883–1893 he lived in Rome, and became increasingly influenced by the Italian Renaissance and antiquity.

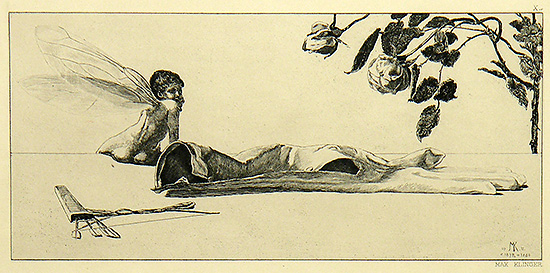

His best known work is a series of ten etchings entitled Paraphrases about the Finding of a Glove (printed 1881). These pictures were based on images which came to Klinger in dreams after finding a glove at an ice-skating rink. In the leitmotivic device of a glove – belonging to a woman whose face we never see – Klinger anticipated the research of Freud and Krafft-Ebing on fetish objects.

In this case, the glove becomes a symbol for the artist’s romantic yearnings, finding itself, in each plate, in different dramatic situations, and performing the role that we might expect the figure of the beloved herself to fulfil. Semioticians have also seen in the symbol of the glove an example of a sliding signifier, or signifier without signified—in this case, the identity of the woman which Klinger is careful to conceal. The plates suggest various psychological states or existential crises faced by the artist protagonist (who bears a striking resemblance to the young Klinger).

Paraphrases about the Finding of a Glove by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Printed 1881.

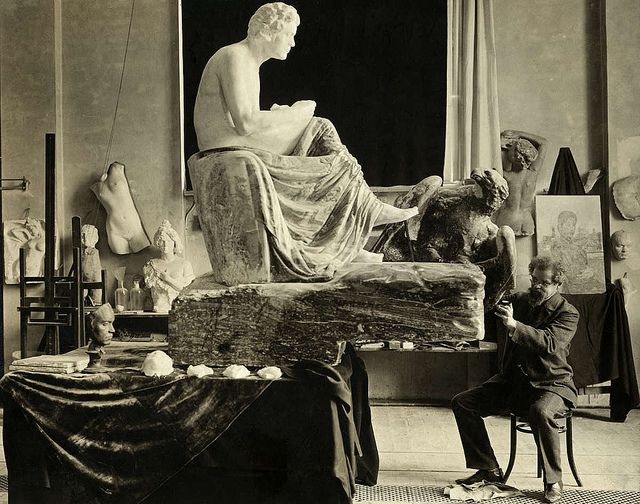

Klinger traveled extensively around the art centres of Europe for years before returning to Leipzig in 1893. From 1897 he mostly concentrated on sculpture; his marble statue of Beethoven was an integral part of the Vienna Secession exhibit of 1902.

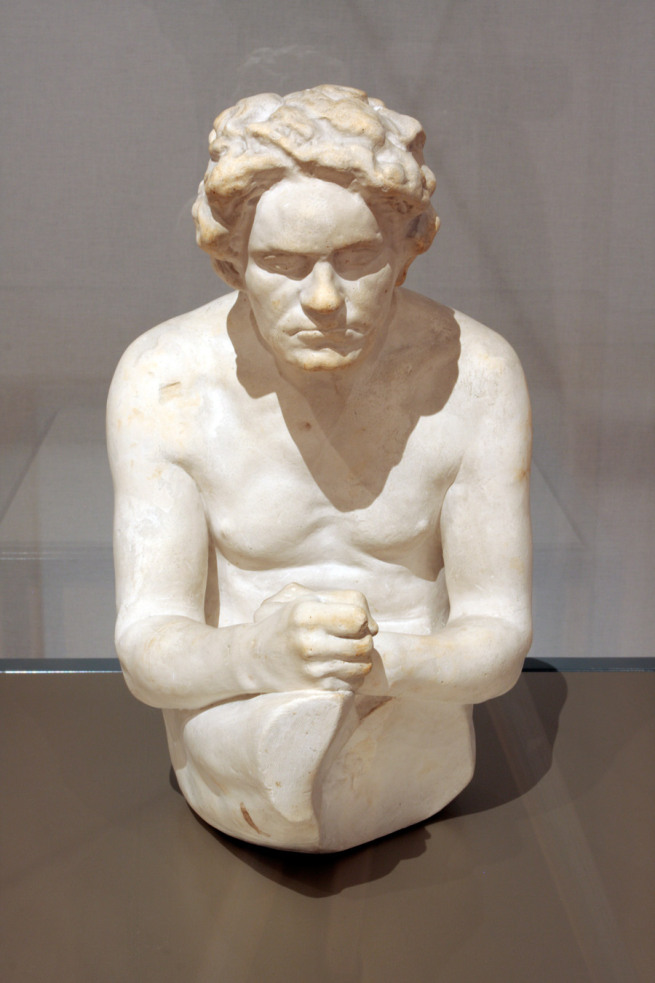

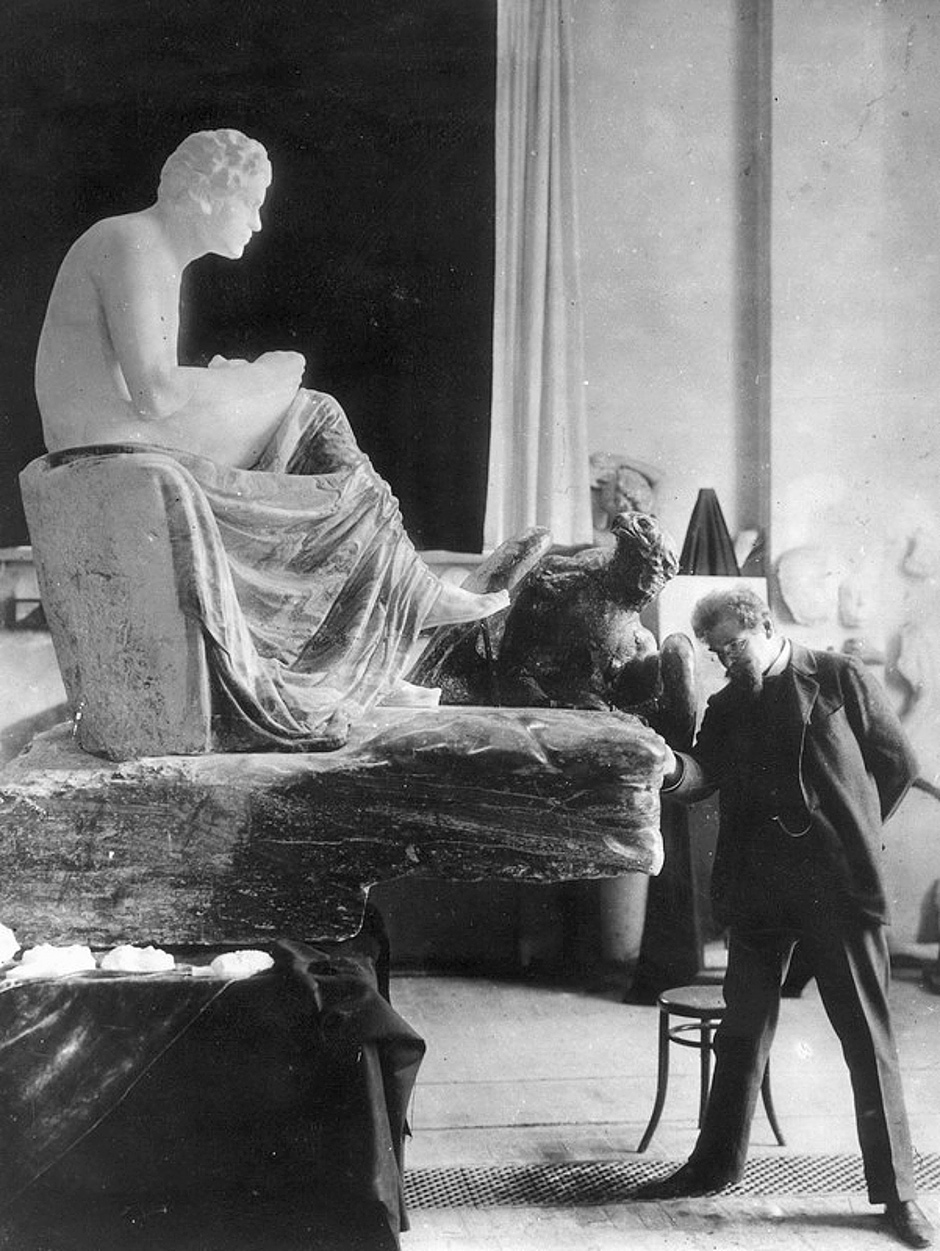

Beethoven (plaster) by Max Klinger (1857-1920), 1902.

1902 Beethoven Statue at the Secession

The Vienna Secession’s fourteenth exhibition, dedicated to Ludwig van Beethoven, was one of the movement’s most widely attended and popular shows. The Secessionists revealed their ideas about art, space, and experience through various artistic contributions paying tribute to the great composer.

Year 1902. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) statue by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Secession (association).

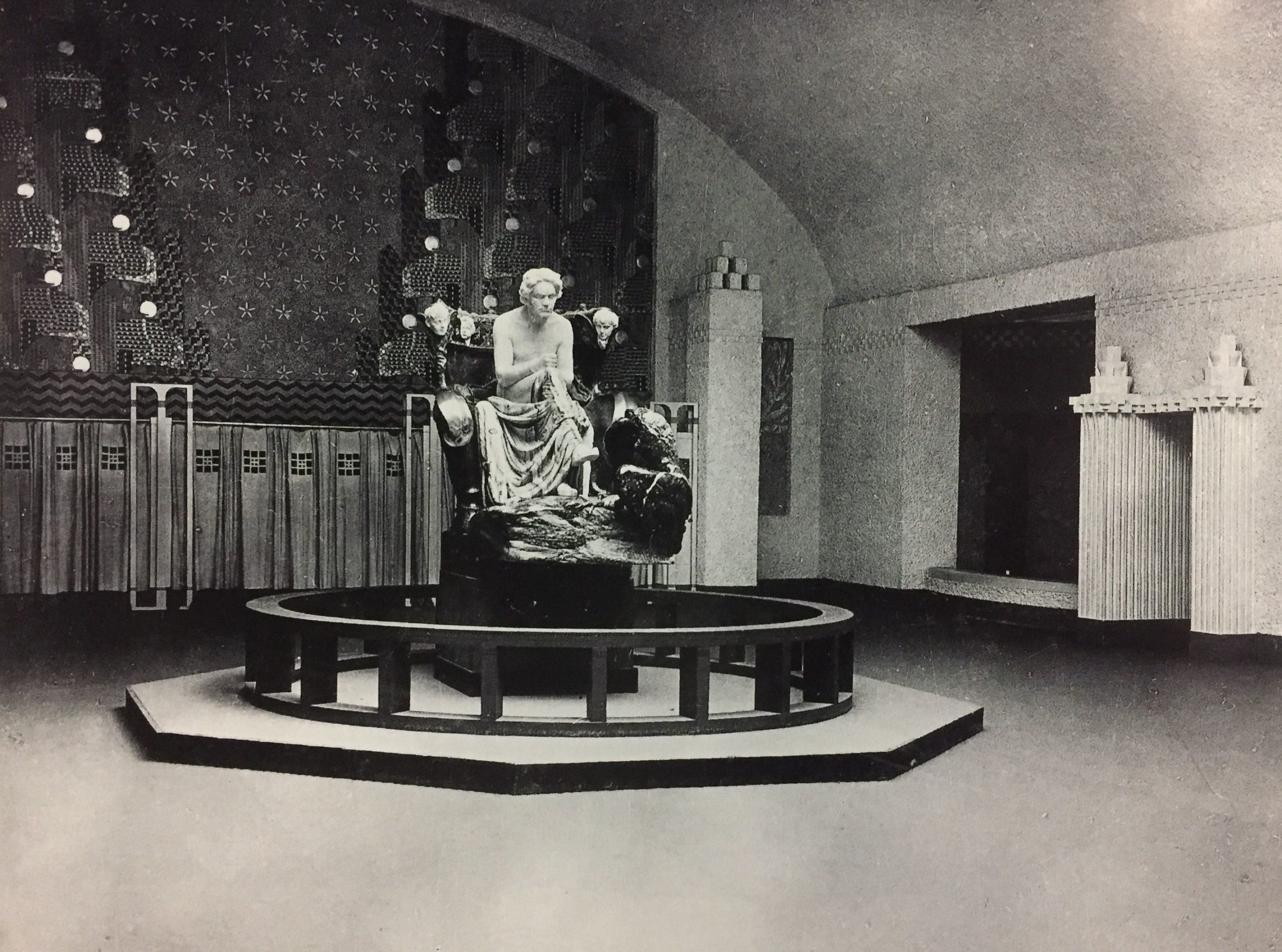

A total of twenty-one artists participated in the exhibition. Two of the most recognizable were Max Klinger, an honorary member of the Secession from Leipzeig, and Gustav Klimt, the Secession’s president. Klinger’s statue of Beethoven was the exhibition’s centerpiece and, as such, was placed in the middle of the Secession House’s main hall. Klimt’s frieze was originally meant to supplement Klinger’s piece, but it later became the more famous of the two, and one of Klimt’s most recognizable works.

Year 1902. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) statue by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Secession (association).

Klinger’s statue of Beethoven was roundly criticized. While most revered Beethoven as a modern father of music, Klinger chose to depict the icon naked and crouching. Most international and Viennese critics found Klinger’s interpretation of Beethoven confusing, if not repellant. One wrote: “The ‘Homage’ that the Secession extols on Max Klinger’s Beethoven Statue . . . unmistakably reveals that they could think of no greater honor for Beethoven than to stick him in the middle of an Assyrian bathhouse” (Celenza, “Music and the Vienna Secession: 1897–1902,” 210).

While most critics did not understand Klinger’s representation (reviews from the Viennese music community are conspicuously absent), some recognized the sculpture’s magnificence and acknowledged its detailed symbolism. Klinger had dedicated fifteen years (and a significant investment of 150,000 marks) to his vision.

On the back of the throne appear Biblical scenes, one of which some scholars believe depicts Beethoven as John the Evangelist, a thesis supported by the eagle (John’s biblical symbol) near Beethoven’s feet. The statue is made of the finest marble, ivory, and bronze and weighs an epic 5,000 kilos.

Year 1902. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) statue by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Secession (association).

The aforementioned criticism that Klinger’s statue resembles an Assyrian bathhouse-goer, however, is not unfounded; rather, it reveals a particular goal of the Secessionists: to create Raumkunst or “spatial art.” The men of the Secession wanted their exhibition (the building, the art, the furniture, and even the “third space” of the printed press) to be an all – encompassing, spatial experience for the viewer – something one could abstractly liken to the captivating moment of entering a bathhouse.

With this goal in mind, the Secessionists designed the main hall, the home of Klinger’s statue, as a Tempelkunst or a place specifically designed to complement the “visual and philosophical essence” of a work of art (“Music and the Vienna Secession: 1897-1902,” 208). Similar perhaps to an Assyrian temple rather than a bathhouse, the main hall was very much a place for veneration.

Year 1902. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) statue by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Secession (association).

The Secessionists’ goal of providing an experiential exhibition, however, did not begin and end with the building, press, and interior design. Even the works of art were themselves infused with this idea. Richard Wagner, the conductor of one of the most famous performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1846), coined the term “absolute music” in the performance’s program booklet. The term refers to a piece of music, such as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, that is so complete in and of itself that it is nearly perfect.

Wagner, along with some contemporaries (most notably Friedrich Nietzsche), rejected this idea of “absolute music.” Instead, he promoted the idea that music as transcendent as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony needs words, specifically poetry, in order for people to fully comprehend the piece.

To this end, Wagner put the Fourth Movement of Beethoven’s Ninth to Friedrich Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy.” Wagner’s rejection of “absolute music” influenced the Secessionists’ ideas about their exhibition space, and also specifically Gustav Klimt, who fashioned part of his famous Beethoven Frieze, a segment referred to as “Ode to Joy (This Kiss to the Whole World),” after the ideas behind Wagner’s 1846 performance.

Year 1902. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) statue by Max Klinger (1857-1920). Secession (association).