Transcript

The beginning of Symphony with a funeral march may well be considered typically malaria. Both the second and third symphonies made ample use of the funeral march to set the stage for the entire work, presenting the tragic elements and antagonistic forces to be overcome when each of these symphonies reaches its conclusion. Mahler also included a funeral cortege in his First Symphony and in his Wunderhorn song der Tamboursg’sell . Earlier composers such as Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Chopin incorporated funeral martyrs in their works. Haydn’s military symphonies third movement has one Beethoven’s third Symphony second movement, Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream incidental music and show pounds Piano Sonata number two and B flat minor all have one, but more gives special purpose to this funeral march, making it representative not only of death itself but of the negative destructive side of the human spirit establishes the dramatic frame of reference for the entire Symphony. The overcoming of humanity’s tragic fate, through a struggle between positive and negative forces during which diverse elements of the human spirit are explored and integrated into the substance of the symphonies lifeworld thus to achieve fuller self-understanding. Although the undeveloped repetition of the funeral march theme may seem monotonous, there is a method in its own very treatment. In Nietzschean terms may connote the eternal return of human suffering, the endless cycle of the tragic fate of mortality. The monotony of the main themes many repetitions contrasts with the trio, which response to the tragedy, with outrage and deep sorrow in different ways with each reprise. Only perhaps in Revelge, the Wouderhorn song, had Mahler expressed his anger at the senseless injustice of human suffering with such ferocity as he does in the first trio. The contrast between brooding melancholy and ferocious anger is as extreme as it gets in a single movement of a Mahler symphony. Music becomes seething with ill-tempered rage. Sudden violent outbursts abruptly forgo transition, as divergent mood swings arise without warning, flattered major and minor keys taint the music with a pathetic stain.

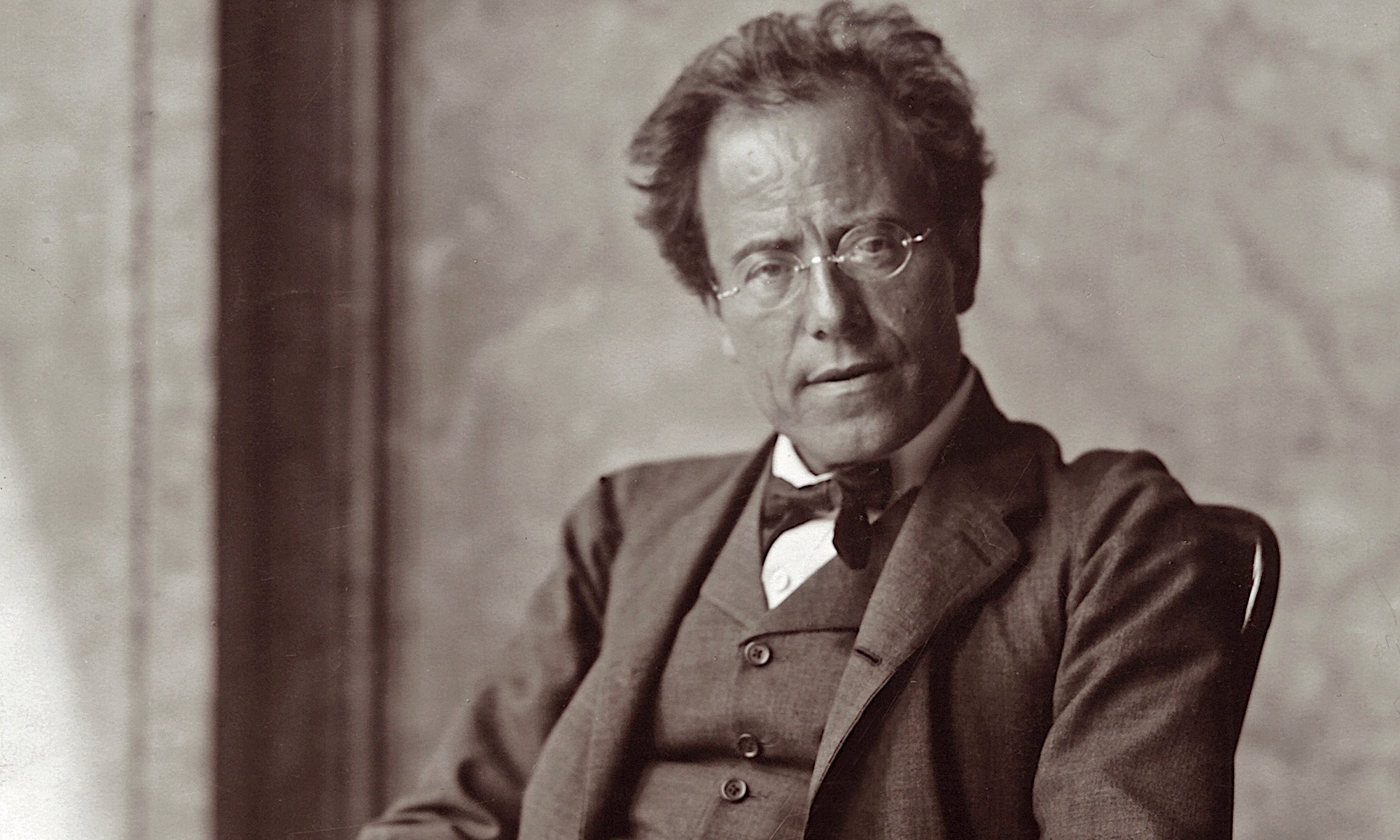

Motivic elements such as the opening trumpet figures, and a rising minor ninth that falls to the octaves are wrenched from melodic material or rhythmic accompaniment, and use throughout the symphony as symbols of tragic fate, and Mahler’s and rage reaction to it. All these elements combined to generate a movement of profound patels more deeply expressive of tragedy and unrestrained and his ferocity than in any other music written before the turn of the last century. Unlike mother’s earlier funeral marches, the first movement begins with an introduction of considerable length, 34 bars, on a single unaccompanied instrument, the trumpet, Mahler pronounces the tragic fate of humankind. man appears alone, as if stark naked and left with no support or protection to face ultimate annihilation. The solo trumpets military fanfare set in the slow even and deliberate tread of a funeral procession begins with a figure that recalls the so called fate motto from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Here it is.

In Mahlerian terms, Mahler creates a full-length introductory subject out of military tattoos associated in the previous symphonies with the hero. As in the Second Symphony, the hero has died and is being led to his grave, the source of this extensive opening sequence of trumpet tattoos is the der Kleiner Appell from the first movement of the Fourth Symphony.

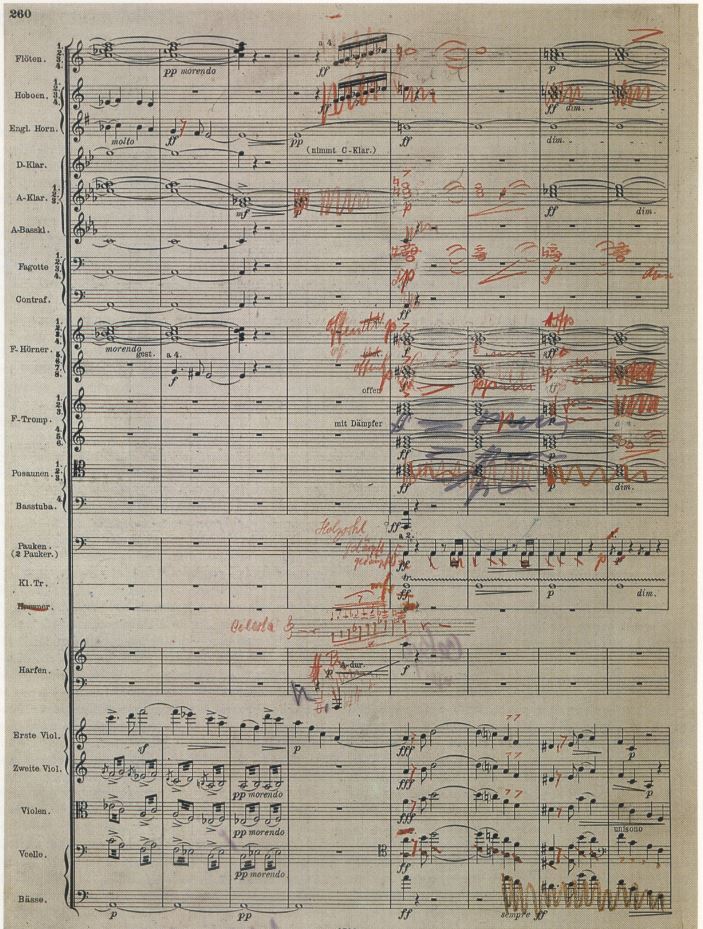

Mahler forces us to consider not only how the two symphonies relate, but whether this relationship puts the earlier Symphony in a new perspective. As a focal point in the fourth, the appearance of der Kleiner Appell to open the fifth may be considered as the fulfillment of a prophetic vision. In the fourth, it happened unexpectedly in the midst of a joyful frolic, demolished by an orchestral explosion, in the fifth that comes out of nowhere, is played without accompaniment to any kind, including any steady funeral march beat. The triplet figure a Beethoven’s fate motto takes on motivic significance, we’ll call it motive x, is a tragic predisposition to life that colors the symphonic world of part one. The same triplet figure played an important role in the funeral march from the first movement of both the second and third symphonies. By combining the motive of the hero with the Beethovenian fate motif, Mahler presents the essence of the human dilemma. To be the hero of one’s own life, one must overcome the painful sense of doom that thoughts of death can engender and affirm life. The trumpet expands upon the model feet, adding dotted rhythms characteristic of Mahler’s march music, they reach higher and higher until the entire orchestra takes over, with a massive thrust of a major on a semi cadence. Then the trumpet continues its fatalistic call on dotted rhythms accompanied by rhythmic replicas of the opening tattoos and the full orchestra. Three powerful chords form an elongated version of the terror motive with which the finale of the second Symphony begins. They give way to the opening tap to thrust out by the entire orchestra in a furious volley of triplets that express outrage at the cruel fate of the hero, in this case, all humanity. While heavy trilled chords synced to the depths, a new motive is heard in the horns. We’ll call it motive, why? three notes in dotted rhythm, the first falling by a half step, the motive of wall, and the second falling by a much wider interval. Here is the motive.

This motive seems to convey a sense of hopelessness in the face of the inevitable it will return in Das Lied von der Erde, during the orchestral interlude between the two poems of their op sheet. The third repetition of motive why falls by a ninth such a plunge being symbolic of a leap of death. A case on like clipped dotted rhythm will call motive z, stated solemnly by trombones now emerges.

The skip step rhythm of motive z provides the basic funeral march tread, which is later incorporated into the main theme of the movement soon to appear, softly and haltingly the moody funeral march theme begins very softly in first violins and cellos. Mahler has the violins play in their low register and the cellos in their high register, forming almost a unison-like effect, but with a slightly darker hue than if given to the violins alone. Pizzicato notes on strong beats mark the temple.

For the most part, this solemn tune functions as the principal theme of the movement. It is rather mild for a funeral march, certainly not as morose as the one appearing in Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, or as plodding as in Chopin second Piano Sonata. In fact, this funeral march theme sounds more like the third subject of the Adagio movement from Bruckner Sixth Symphony, which is doleful in character but is uncharacteristic of a funeral march. Yet like both the Beethoven and Chopin themes, Mahler’s funeral march is built around dotted rhythms that rise or fall by a half step, relating them to motive z, and giving them a rocking motion suggestive of a Jewish lullaby. A short lilting phrase appears in the first part of a theme that seems out of character for funeral march music. I have note followed by a grace note a dotted rhythmic figure and ending with a little Slavonic stand step the entire two bars forming a gruppetto.

This tuba thematic fragment relates to a similar phrase in the lighthearted klezmer music that occurs during the funeral march movement of the First Symphony.

There this dance rhythm seems more appropriate for the light-hearted folk theme in which it appears than it does in the context of this funeral march. Also, in contrast, with the first symphonies funeral march, the funeral procession that opens a fifth evokes no memories of happier times to relieve the sorrow of mourning. Instead, a change in mood only brings on raging anger.

After a full cadence, the Beethovenian feet model of the opening fanfare returns in the cellos accompanied by the processional beat of motive Z, soon the entire orchestra builds on the triplet tattoos from the introduction until the trumpet again picks up its opening fanfare, intensified by rapid ascending and descending scales. As before, the reprise of the introduction concludes with a series of upbeat triplets for full orchestra connected by a military drum roll and followed by an extension of the trumpet fanfare on the motive why, with trilled, descending chromatics in low woodwinds and strings.

The march theme returns in an extended treatment that varies the theme slightly with each statement and adds more woodwind coloration. The theme is then given over entirely to the woodwinds, when the key changes to a flat set against an inverted variant of the theme and the cellos, woodwinds, and strings alternate in developing the principal theme, while horns trombones, and military side drum add motive Z, that sets the pace for the funeral quarter. When the strings take up the theme at the end of the A section, and the tonality reverts back to C sharp minor. The theme now incorporates motive Y, another instance in which basic rhythmic figures that first appeared will have no thematic significance become part of the theme as it develops.

An abbreviated version of the case on like march phrase of motive Z, with trills against the triplet upbeat to the introduction closes the section and the music dies away, still in the doldrums of profound tragedy. As the march rhythms fade, the third trumpet concludes the A section quietly on motive X from the opening fanfare. Suddenly the fanfare is thrust aside, just as it is about to conclude by the forceful entrance of the olders on an upbeat, that begins a three-note model, consisting of a rising super octave into a falling minor second keynoting wall. This figure is ripped out of the march theme, and disfigured by widening the rising interval to a 12th. It hurdles the music into the first trio in B flat minor with extreme violence, and shocks us out of the gloomy but quiet funeral music of the asexual, racing wildly and furiously the music vents its anger at the injustice of human tragic fate, on a new theme and the first trumpet, propelled by raging eighth note figuration in strings, and fraught with descending chromatics that is sometimes pounded out emphatically on quarter-note triplets. Mahler directs the strings to play as vehemently as possible. syncopated trombone chords add to the tension, repeated falling fourths in the base of the beginning of the trio. Recall the funeral march tread appearing in the first and second symphonies here played in double time. The first part of the trumpet theme consists mainly of wide rising leaps, and descending chromatic dotted rhythms, falling seconds of wall, underlying the tragic character of the theme. This music might be considered as Mahler’s j’accuse against life itself, or its creator, for allowing such unremitting human suffering.

The trumpet theme second part is composed of two arch-like phrases that you’re in for a resolution to the conflict between man’s fate and his longing for redemption, it also relates to the funeral march theme of the A section. With all of its rage, this trio theme still projects a ray of hope, in an arching phrase heard in the solo trumpet at the end of the last segment, this phrase will return in the second movement to counteract an even stronger negative reaction to life’s tragic suffering. As we just heard, in the midst of the trio’s uncontrolled fury, that trumpet tattoos of the introduction abruptly return, hurdling out their triplet rhythms motive x two which is added in a falling minor second of wall, only to be subjected to a deluge of wild string figuration.

Woodwinds ring out fragments of the trio theme, after a timpani volley again on falling fourths. The horns take up the arching phrase of the trumpet theme and force it to rise heavenward, seeking relief from the painful recall of human tragedy. Just as the trio section seems to be headed toward a conclusion, it revives with renewed fury.

In this second part of the first trio, the rising theme of hope becomes more prominent.

The music presses onward and upward on the trumpet’s angry theme, set against the hopeful rising theme and violins, soaring to greater heights than before. Emphasis on weak beats connotes a sense of undaunted courage in the face of inevitable defeat. The theme reaches a powerful climax on the motive of the wall only to burst forth yet again on the enraged string figuration that accompanies the trumpet’s theme.

At the beginning of the trio, in the midst of the anger theme, the opening trumpet fanfare returns as if out of nowhere to close the first trio. It is apparent that no resolution has yet been achieved although the return of the rising theme of hope in the horns is a sign that all may not yet be lost.

The recurrent use of the trumpet fanfare as a bridge to the return of the A sections funeral march gives the movement a rando like quality. As the tonality changes back to the tonic C sharp minor, shuttering chromatic tremeloes with accents on weak beats, add an icy chill to the funeral music’s tragic character. Soon the entire introduction returns with the same sequence of strong chords, and upbeat triplets from the end of the movements opening section.

With the inevitability of pure logic, the funeral march theme now marked shwer: heavy, returned softly and woodwinds against the march tread of moto Z, or trumpet players and even gloomier variation of it. Then the opening of the trio theme and trues, reminding us of its angry accusation, after a modulation into B flat minor, a key of the first trio, a trio theme shifts to woodwinds and solo horn in a calmer mood to usher in a brief statement of the swaying phrase from the second part of a funeral march theme. Another variation on this theme follows inverting the dotted rhythmic figure with which it begins, adding a gruppetto as well as the opening phrase from the trio theme, thereby both absorbing and tempering its wrath. The cadence with which this dramatic variation concludes is a direct quote from the first song from the Kindertotenlieder cycle, which is sung to the words Heil sei dem Freudenlicht der Welt, Hail to the joyful light of the world, hear the invocation of light as a symbol of redemption brings hope, as the A section dies away on a more subdued statement of the trumpet tattoo, played quietly on the timpani.

Here is the phrase from the first song of Kindertotenlieder.

As the triplet upbeats of the opening fanfare subside and the timpani the second trial begins in a completely different mood than before. Its violent anger has disappeared, instead, the solemnity of the funeral march carries over into the second trio. Although Paul Becker considers the violin theme with which the second trio begins to be a new theme, it is actually a transformation of the trumpet theme from the first trio, now mollified into a mournful song-like melody, akin to the funeral march, the motives X and Y from the opening of the funeral march accompany the second trio theme, thus conflating march and trio. They’re rising ninth that give way to falling minor seconds sound like little heartbreaking sighs. Cellos take up the variegated trio theme briefly until it is transferred to the violin, a horn asserts the rising theme of hope as if to instill a sense that there may yet be light at the end of this long dark tunnel of despair.

Strings take up the theme of hope, as in the first trio, again reaching heavenward for some sign that redemption is possible. They managed to arouse some passion from the beleaguered spirit as the tempo presses forward on a brief recollection of the string figuration from the first trio, but it’s no longer ill-tempered as before. The theme of hope, its fragmentation, producing the motive of longing struggles with the trio theme, and becomes more assertive, as its anguish intensifies until both themes merge into overpowering tragic chords, marked clog and sorrowful that explode out of the entire orchestra. Here the movement reaches its climax, all of the torture was a pain the dreadful thoughts of death have brought seem to be distilled in these overwhelming sustained chords. From a great height, the music descends in stepwise motion, held back for emphasis on shivering tremolo strings that chill the atmosphere. A sense of unremitting bubble hopelessness overwhelms the music as it gives way to total collapse, trombones menacingly and tone and ascending chromatic figure in half-note triplets, out of which the trumpet fanfare returns in an abbreviated version of the movement’s introduction, string tremeloes descend chromatically, adding a tremulous quality to the dark, solid music. The funeral march continues on the following dotted rhythms of the trumpet fanfare, anticipating the next movement. Cellos and basses take up this falling figure in a heavy-laden temple and in orientation, and the funeral procession slows down to a crawl.

As the tonality comes to rest on its home key of C sharp minor, the solo trumpet begins for the last time the solemn fanfare with which the movement began. This time its upbeat triplets are punctuated by woodwinds and skeletal rattling of colonial strings with intermittent timpani rolls. The tattoos shift from the beat trumpet to muted F trumpet and rise higher, each triplet figure broke off by the distance sound of a soft bass drum roll.

Mahler creates the sensation that the procession is gradually fading away, as he transfers the last triple tattoo to the flute, which holds on to its final note, the tonic for 2 long measures. Only the distant roll of a bass drum can be heard after the flute ceases, then a sudden jolt on a strong pizzicato note in bass strings pointedly punctuates the conclusion of the movement with an exclamation point.

One is left with a feeling of utter desolation. The terrible questions about the meaning of life and death remain unanswered. The conflict between opposing forces of the human spirit unresolved.

By Lew Smoley