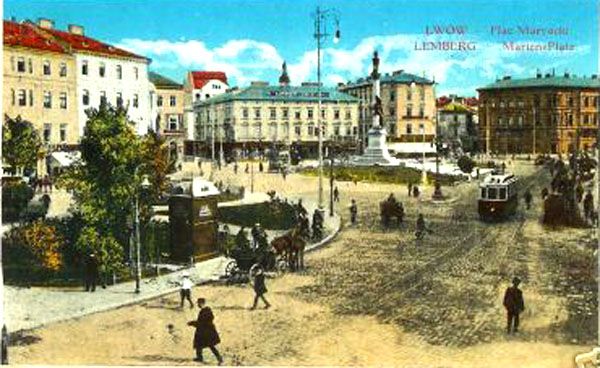

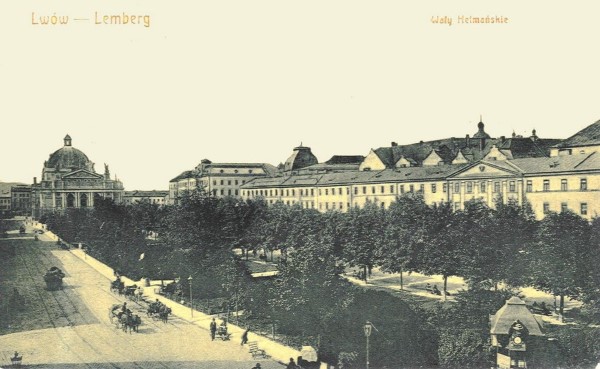

- Also: Lwów, Lwow, Lvov (Poland). Now Lviv in Ukraine.

- In 1903 capital of the Austrian province of Galizia.

- Year 1903.

Lviv is located on the edge of the Roztochia Upland, approximately 70 kilometers (43 miles) from the Polish border and 160 kilometers (99 miles) from the eastern Carpathian Mountains. The average altitude of Lviv is 296 meters (971 feet) above sea level.

Its highest point is the Vysokyi Zamok (High Castle), 409 meters (1342 feet) above sea level. This castle has a commanding view of the historic city centre with its distinctive green-domed churches and intricate architecture.

The old walled city was at the foothills of the High Castle on the banks of the River Poltva. In the 13th century, the river was used to transport goods. In the early 20th century, the Poltva was covered over in areas where it flows through the city; the river flows directly beneath the central street of Lviv, Freedom Avenue (Prospect Svobody) and the Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet.

Habsburg Empire

In 1772, following the First Partition of Poland, the region was annexed by the Habsburg Monarchy to the Austrian Partition. Known in German as Lemberg, the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. Lemberg grew dramatically under the Austrian rule, increasing in population from approximately 30,000 at the time of the Austrian annexation in 1772, to 206, 100 by 1910; while the poverty in Austrian Galicia was raging.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries a large influx of Austrians and German-speaking Czech bureaucrats gave the city a character that by the 1840s were quite Austrian, in its orderliness and in the appearance and popularity of Austrian coffeehouses.

In 1773, the first newspaper in Lemberg, Gazette de Leopoli, began to be published. In 1784, a German language university was opened; after closing again in 1805, it was reopened in 1817. German became the language of instruction.

During the 19th century, the Austrian https://mahlerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MF-Projects-2.pngistration attempted to Germanise the city’s educational and governmental institutions. Many cultural organisations which did not have a pro-German orientation were closed. After the revolutions of 1848, the language of instruction at the university shifted from German to include Ukrainian and Polish. Around that time, a certain sociolect developed in the city known as the Lwów dialect. Considered to be a type of Polish dialect, it draws its roots from numerous other languages besides Polish.

In 1853, it was the first European city to have street lights due to innovations discovered by Lviv inhabitants Ignacy ?ukasiewicz and Jan Zeh. In that year kerosene lamps were introduced as street lights. Then in 1858, these were updated to gas lamps, and in 1900 to electric ones.

After the so-called “Ausgleich” of February 1867, the Austrian Empire was reformed into a dualist Austria-Hungary and a slow yet steady process of liberalisation of Austrian rule in Galicia started. From 1873, Galicia was ‘de facto’ an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary with Polish and Ukrainian (or Ruthenian), as official languages. Germanisation was halted and the censorship lifted as well.

Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm and provincial https://mahlerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MF-Projects-2.pngistration, both established in Lviv, had extensive privileges and prerogatives, especially in education, culture, and local affairs.

The city started to grow rapidly, becoming the 4th largest in Austria-Hungary, according to the census of 1910. Many Belle Époque public edifices and tenement houses were erected, the buildings from the Austrian period, such as the Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet built in the Viennese neo-Renaissance style, still dominate and characterise much of the centre of the city.

During Habsburg rule, Lviv became one of the most important Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish cultural centres. In Lviv, according to the Austrian census of 1910, which listed religion and language, 51% of the city’s population were Roman Catholics, 28% Jews, and 19% belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Linguistically, 86% of the city’s population used the Polish language and 11% preferred the Ukrainian language.

At that time, Lviv was home to a number of renowned Polish-language institutions, such as Ossolineum, with the second largest collection of Polish books in the world, Polish Academy of Arts, National Museum (since 1908), Historical Museum of the City of Lwów (since 1891), Polish Copernicus Society of Naturalists, Polish Historical Society, Lwów University, with Polish as official language since 1882, Lwów Scientific Society, Lwów Art Gallery, Polish Theatre, Polish Archdiocese.

Furthermore, Lviv was the centre of a number of Polish independence organisations. In June 1908, Józef Pi?sudski, W?adys?aw Sikorski and Kazimierz Sosnkowski founded here the Union of Active Struggle. Two years later, the paramilitary organisation, called Riflemen’s Association, was also founded in the city by Polish activists.

At the same time, Lviv became the city where famous Ukrainian writers (such as Ivan Franko, Panteleimon Kulish and Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky) published their work. It was a centre of Ukrainian cultural revival. The city also housed the largest and most influential Ukrainian institutions in the world, including the Prosvita society dedicated to spreading literacy in the Ukrainian language, the Shevchenko Scientific Society, the Dniester Insurance Company and base of the Ukrainian cooperative movement, and it served as the seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Lviv was also a major centre of Jewish culture, in particular as a centre of the Yiddish language, and was the home of the world’s first Yiddish-language daily newspaper, the Lemberger Togblat, established in 1904.

- Flute virtuoso and composer Albert Franz Doppler (1821-1883) was born in Lemberg.

- Pianist Mieczyslaw Horszowski (1892-1993) was born in Lemberg.