Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858-1921) (published 1923)

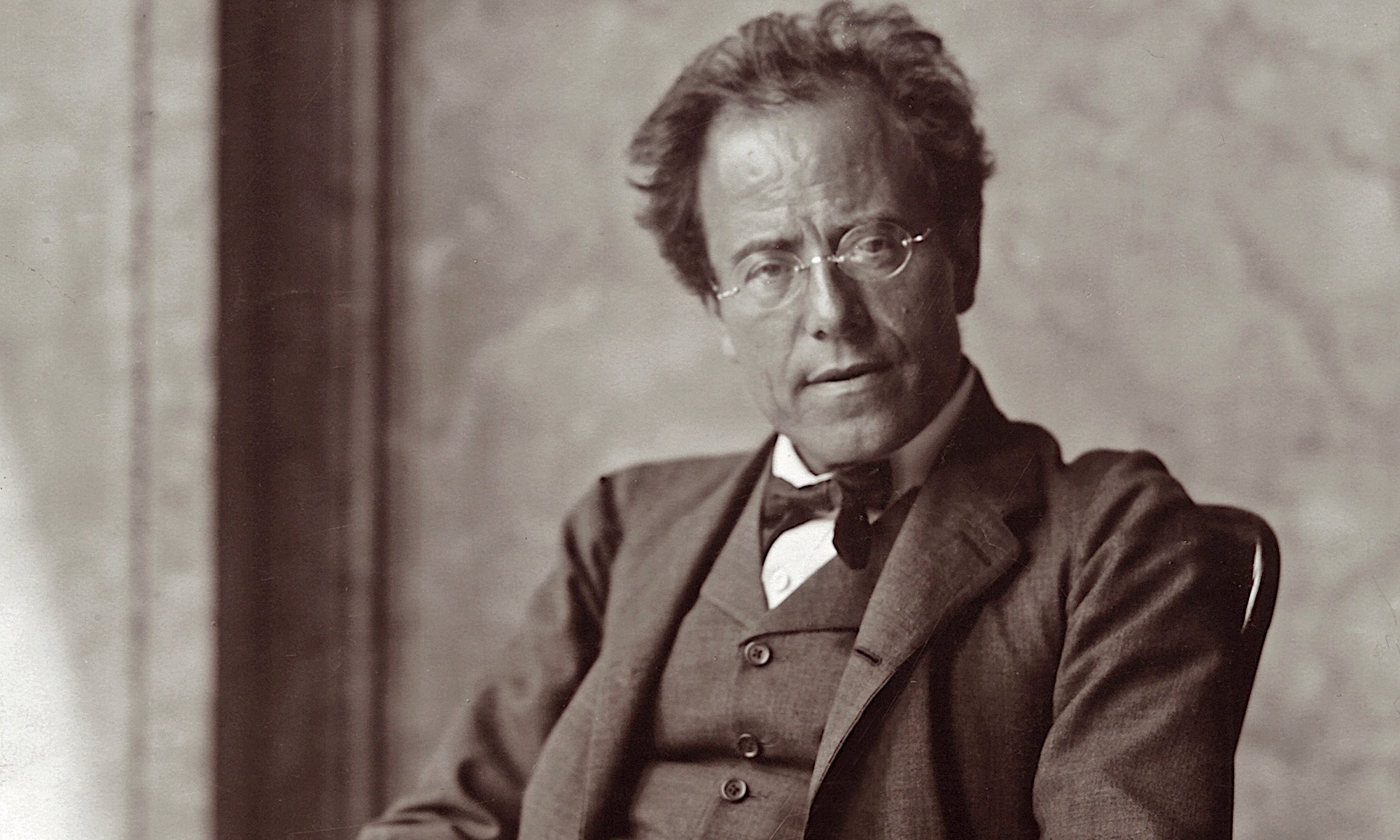

Mahler, whose outward appearance gives so much cause for criticism, used to reply to reproaches about it: ‘I can’t live an aesthetic life; my personality and temperament are otherwise inclined. And if I weren’t what I am, I couldn’t write the symphonies that I do.’

Recently, coming to fetch me at a friend’s he rushed into the house like a whirlwind. He talked brilliantly, in the most exuberant mood, and swept everyone off their feet with his high spirits and sparkling merriment. But after a short time – who knows what had come into his head! – he suddenly fell silent as the grave, sat there lost in his own thoughts, and uttered not another word until he left.

So changeable and inconsistent is he by temperament, that he is never the same for an hour at a time; and with each shift in his own view of things, he seems to see everything around him – particularly where his closest friends and relatives are concerned – in a new light. But in spite of these changes of mood his loyalty is one of his strongest characteristics. Like the indicator of a pair of scales finding the point of balance, he always returns to anyone he has once chosen and taken to his heart. In this respect one could count on him utterly.

He is extremely forgetful and absent-minded, because inwardly preoccupied and distracted. In fact, he used to be much more so. The strangest things would happen to him! The most extreme instance occurred in his youth, while drinking black coffee at a party. Without thinking, he stirred the cup with his cigarette instead of his spoon and then, imagining that he had smoke in his mouth, blew coffee across the table right into his hostess’s face!

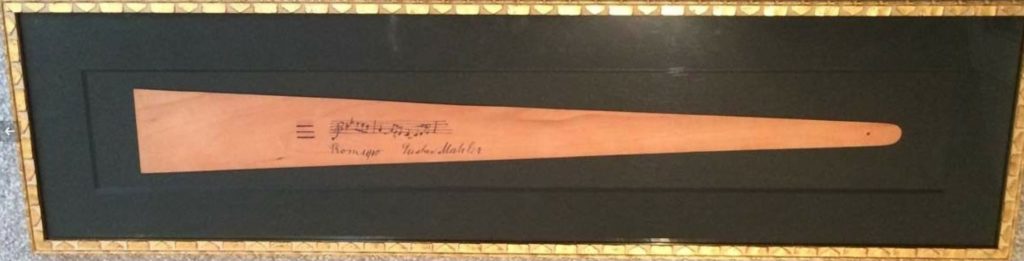

Innumerable tales of this kind are told of him. His Conservatory colleague Winkler told me that once, after a rehearsal of his piano and violin sonata, he ran out of the Musikverein – this was in winter – so lost in thought that he forgot his coat, stick and hat. In fact on the Ringstrasse he even dropped half his music! Luckily some of his colleagues were following, picked up the manuscript and returned it to him safely, along with his clothing.

Needless to say, the neatness and cleanliness of his dress leave everything to be desired. His bootstraps are always sticking up, or a bit of shoelace is hanging out. If he goes out in the morning without being looked over, he often comes back at noon with the white traces of tooth-powder or shaving-soap still on his mouth or cheeks. Sometimes he even forgets to comb his hair, and runs around all day like a Struwelpeter (The figure in the children’s cautionary picture-book, who would not look after his hair or finger-nails.). However, this happens only when he’s travelling; at home, he washes daily from head to foot, including his hair.

Naturally, he is just as untidy in his room. When he leaves it in the morning, it looks as if the Devil had camped out there! The bed is in the most disordered state possible: bolster and bedspread on the floor, the sheet rolled up in a ball in some corner of the bed. Comb, toothbrush, towels and soap are strewn about the room or on the bed, envelopes and bits of paper in the washbasin, nightshirt and dirty linen from one end of the floor to the other.

Most characteristic of Mahler is his walk. It excites notice everywhere – even the children poke fun at it. As he stamps along, he twitches with impatience with every step he takes, like a high-stepping horse, or a blind man feeling his way. If he is engaged in lively conversation with anyone, he grabs him by the hand or by the lapels and forces him to stand where he is. Meanwhile, he himself, growing more and more excited, stamps the ground with his feet like a wild boar.

It’s most extraordinary that Mahler – with his fine sense of rhythm – cannot walk two successive steps at the same pace. Instead, he changes his speed so often that it is utterly impossible for anyone to keep in step with him. Rowing in a boat is even worse, for he makes wildly irregular strokes – now in quick succession, now quite slowly. What’s more, he becomes quite furious if his rowing companion – who is always to blame for everything – bumps oars with him.

Mahler, who is of less than average height, has an apparently-delicate frame, being slight and lean in build. But many a more powerfully-built person might envy him his extraordinary strength and suppleness. For example, he shows great skill and stamina in athletics; he’s an outstanding swimmer, cyclist and mountaineer. I have myself never seen him skate or do gymnastics. In Budapest, when Justi was quite ill, he used to carry her up three flights of stairs in her winter clothes and furs, in order to spare her the climb. And she’s heavier than he is! And no giant could compare with him in his effortless control of the mightiest pianos.

It is almost impossible to judge Mahler’s age from his face. One moment it seems as youthful as a boy’s; the next, it’s furrowed and aged far beyond his years. In the same way, his whole appearance can change from one extreme to the other within a few days, even a few hours. Sometimes he looks full in the face, sometimes strained and haggard. This all depends on the perpetual and swift transformations of his whole spiritual and physical nature. Each transformation possesses him completely, spontaneously and with utmost intensity.

When he is in good spirits, he often looks boyishly young, perhaps because he does not wear a beard. Actually, when he was a young man he had quite a luxuriant, bushy black one. He was wearing it some seventeen years ago when I first met him, and did not have it shaved off till he moved to Prague. Now that the beard’s gone, there’s something about his face, to a superficial eye, that reminds one of an actor’s. But 1 hate to hear people say so. Actually, nothing could have less in common with the empty, artificial and impersonal expression of an actor than Mahler’s features – so intense, so clearly reflecting his spirit and soul in their every configuration, so frank and striking. Is it possible that the outward appearance would not faithfully reflect the inner man?

In earlier years, I used to urge Mahler to let the beard grow again in some form. He protested vigorously: ‘What are you thinking of? Do you imagine that I go clean-shaven out of whim or vanity? I have a very good reason for it. When I am conducting, I communicate with singers and orchestra not only through hand-movements and glances, but also through mouth and lips. I secure the notes with every expression, every tiny facial movement. I can’t do that with my face hidden by a beard. It must be quite free.’

His small, brown eyes are fantastically alive and fiery. I can well believe that some poor devil of a player or a singer might be ready to sink through the ground when Mahler turns his sharp gaze upon him. Neither glasses nor pince-nez (which he wears because he’s short-sighted) can in the least dim those eyes, above which rises his tremendously powerful forehead, in whose bumps and lines you can literally read his thoughts. Two blue veins run jaggedly over his temples (I call them the ‘zigzag lightning veins’) and herald the storm brewing within, by protruding threateningly and conspicuously when he is angry. There can be little more terrifying than Mahler’s head when he’s in a rage. Everything about him burns, twitches and emits sparks, while every single one of his raven-black hairs seems to stand on end separately.

I mustn’t omit to mention a peculiarity in the shape of his head: the straight line from the back of his head to his neck, which reminds one of the head of an otter. Imperious is the hooked nose with its finely sensitive nostrils, and the energetic, rather wide and firm-shutting mouth that conceals a row of irregular, but sound, snow-white teeth. The delicate, rather thin lips, however, are said to betoken a lack of sensuality.

The expression of this mouth, slightly drawn down at the comer – half scornfully, half in anguish – reminds me of Beethoven. But I mustn’t say so in front of Mahler as he is too modest. (He possesses an authentic plaster cast of Beethoven’s features, taken during the composer’s lifetime.) The dourness and severity of Mahler’s mouth are, nevertheless, immediately transformed into their opposite when anything excites his good-natured and humorous laughter. You cannot imagine a more naive, hearty, Homerically boisterous laugh than his. Often, if 1 hear him laughing in the next room or wherever, even without knowing why, I have to laugh aloud myself – so convincing and infectious are his salvoes of merriment.

He must have been like that even as a child. One day, when he had hurt his finger very badly and cried for hours, refusing to be comforted, his father brought him Don Quixote to read. Suddenly his parents heard little Gustav roaring with such loud laughter that they thought he must have gone out of his mind. They rushed to his side, only to find that the adventures of Don Quixote had so taken him out of himself that his really severe pains had guite gone.

See also: Letters from Alfred Roller (1864-1935).