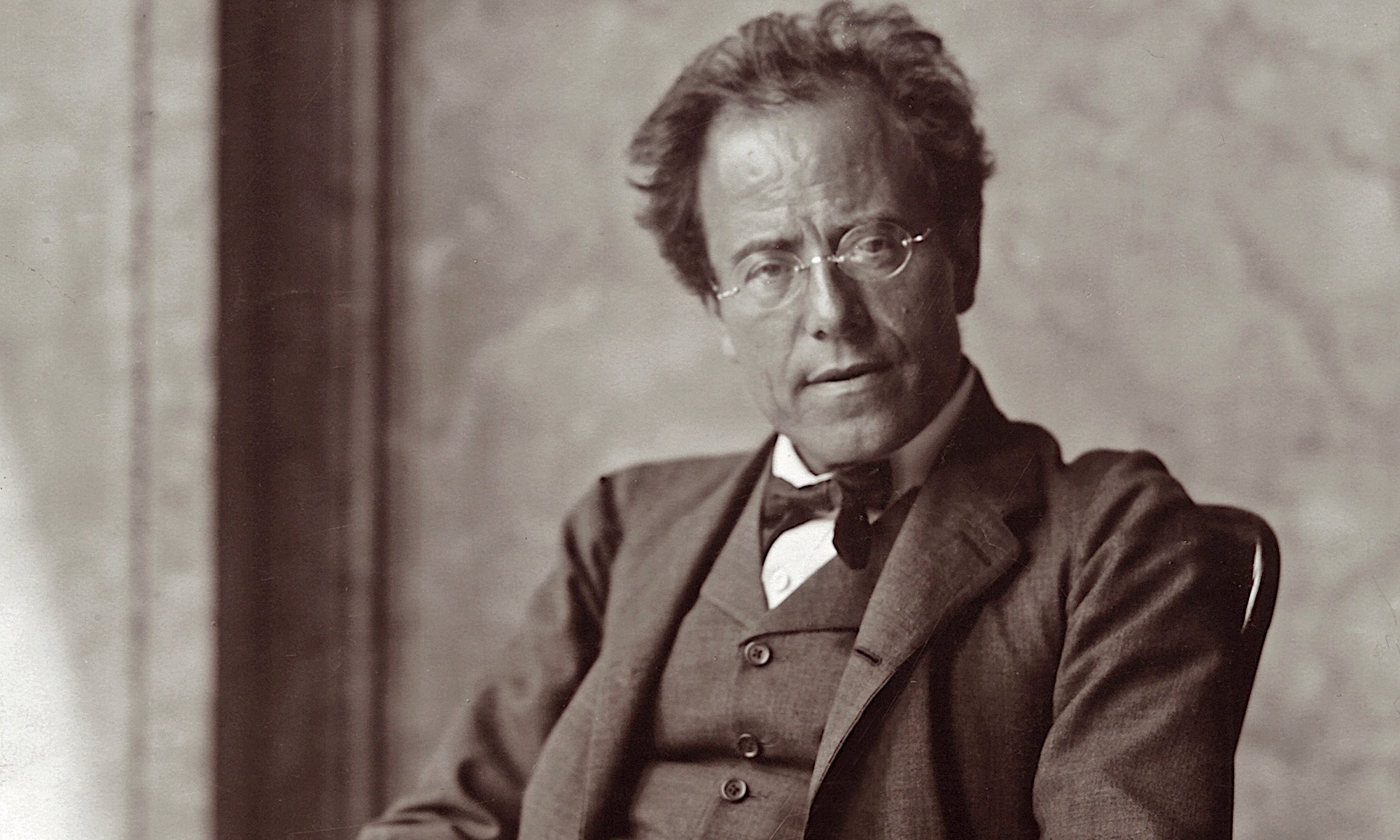

Gustav Mahler’s reading was wide-ranging, extending, as it did, from the classics of world literature to rather more recondite works. Apart from occasional glances as far back as the ancient Greeks and, in particular, to Euripides, Shakespeare was the earliest playwright to engage his attention, which was focused in the main on German classical and Romantic writers, notably Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) but also Hölderlin and E. T. A. Hoffmann.

Among the great humorists whose works he enjoyed were Cervantes, Sterne, Jean Paul (1763-1825) and Dickens, while Dostoevsky and the Dutch novelist Multatuli (see Restaurant Van Laar) were likewise a source of a biding interest. As for more recent literature, Mahler’s reading list was relatively brief, being largely dictated by friendship (Siegfried Lipiner (1856-1911) and Gerhart Hauptmann (1868-1946)), acquaintanceship (Frank Wedekind) or chance encounters (the Russian novelist Dimitri Merezhkovsky, who wrote a successful novel about Leonardo da Vinci and whose essay championing Dostoevsky at the expense of Tolstoi must have appealed to Mahler).

His reading was not limited to belles lettres, however, but also included texts of a more philosophical nature, from Kant, whose works formed part of his reference library, to Frederick August Lange’s History of Materialism and Alfred Edmund Brehm’s Life of Animals, which he is said to have owned in its entirety.

His friend Siegfried Lipiner (1856-1911), who success fully popularized modern science, provided him with information about developments in this field. Unfortunately, Mahler’slibrary has not survived: when Alma had to flee from Vienna in 1938, his books were left behind to be plundered, destroyed and sold. Although a catalogue of them was never drawn up, we are none the less well informed about its contents.