Alexander Lambert (1862-1929).

Alexander Lambert and Josef Casimir Hofmann (originally Józef Kazimierz Hofmann; January 20, 1876 – February 16, 1957) was a Polish-American virtuoso pianist, composer, music teacher, and inventor. Alexander Lambert was a well known piano teacher and director of the New York College of Music.

- Profession: Pianist, pedagogue, Director of the New York College of Music.

- Residences: New York.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 00-00-0000, Year

- Born: 1862 Warsaw, Poland.

- Died: 1929

- Buried: 00-00-0000

Alexander Lambert (1862-1929).

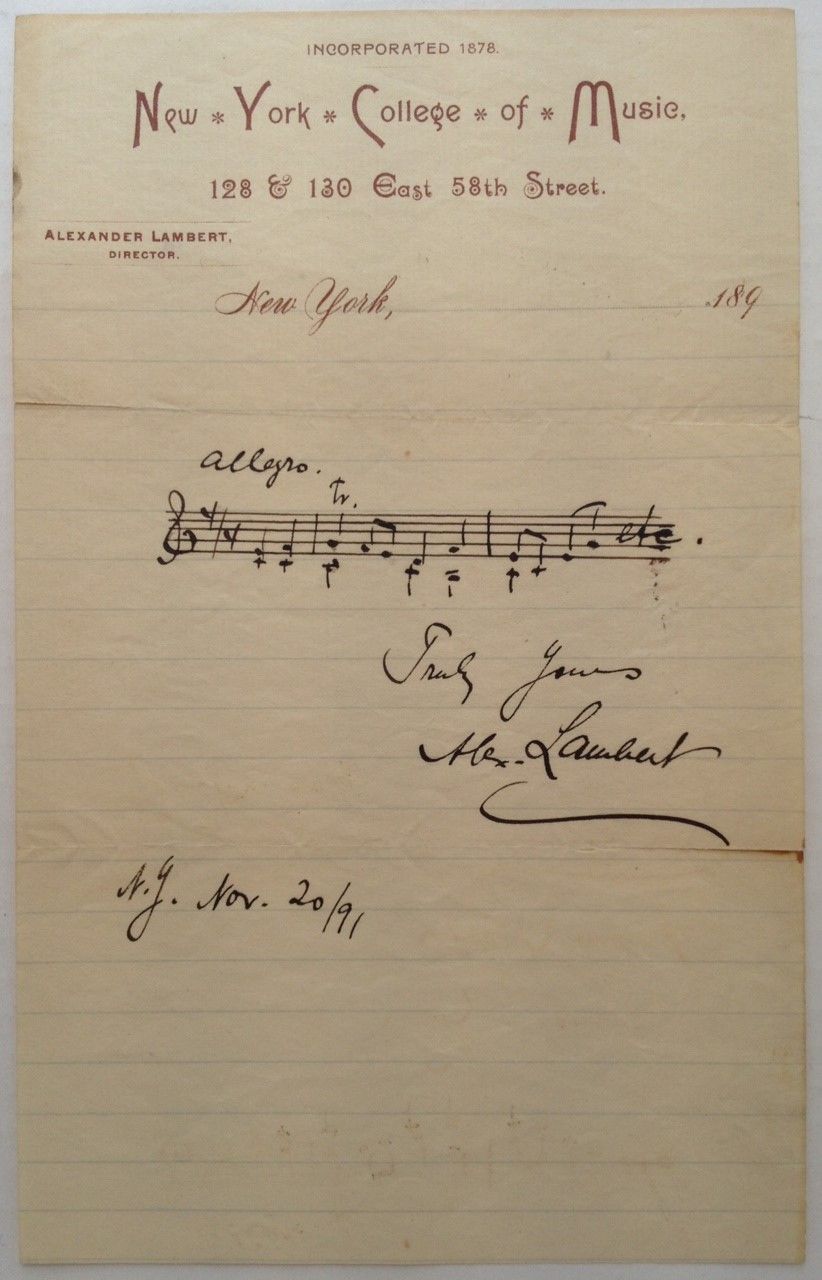

Photo: New York, 1891. unbound. 1 page, 8.25 x 5 inches, New York, November 20, 1891. Three bars of music written in India ink on the letterhead of his New York College of Music. Signed “Truly Yours, Alex Lambert.” Partial tearing along the natural horizontal folds. Very good(-) condition. Friend, teacher, compatriot and collaborator of music with Ignace Paderewski. On one his tours of the United States, Lambert made such a sensation as a composer-performer that he was persuaded to settle in New York City (1888) where he became Director of the New York College of Music. Anytime Paderewski would come to America he would make it a point to visit Lambert and (truncated).

He studied the piano with his father and later with Julius Epstein at the Vienna Conservatory, where Mahler might well have met him. After working with Liszt in Weimar, he moved to New York in 1884 and became director of the New York College of Music (1887-1905). He was the author of several works for piano and of an important teaching manual.

Among American teachers Alexander Lambert takes high rank. For over twenty-five years he has held aloft the standard of sound musicianship in the art of teaching and playing. A quarter of a century of thorough, conscientious effort along these lines must have left its impress upon the whole rising generation of students and teachers in this country, and made for the progress and advancement of American art.

It means much to have a native-born teacher of such high aims living and working among us; a teacher whom no flattery nor love of gain can influence nor render indifferent to the high aim ever in view. There is no escaping a sound and thorough course of study for those who come under Mr. Lambert’s supervision. Scales must be, willingly or unwillingly, the daily bread of the player; the hand must be put in good shape, the finger joints rendered firm, the arms and body supple, before pieces are thought of. Technical study must continue along the whole course, hand in hand with piece playing; technic for its own sake, outside the playing of compositions. And why not? Is the technic of an art ever quite finished? Can it ever be laid away on the shelf and considered complete? Must it not always be kept in working order?

“Have you not seen many changes in the aims of students, and in the conditions of piano teaching in New York, during the years you have taught here?” I asked Mr. Lambert, in the course of a recent conversation.

“Some changes, it is true, I have seen,” he answered; “but I must also say that the conditions attending piano teaching in America are peculiar. We have some excellent teachers here, teachers who can hold their own anywhere, and are capable of producing finished artists. Yet let a pupil go to the best teacher in this country, and the chances are that he or she is still looking forward to ‘finishing’ with some European artist.

They are not satisfied until they have secured the foreign stamp of approval. While this is true of the advanced pianist, it is even more in evidence in the mediocre player. He, too, is dreaming of the ‘superior advantages,’ as he calls them, of European study. He may have no foundation to build upon—may not even be able to play a scale correctly, but still thinks he must go abroad!

Alexander Lambert (1862-1929).

“You ask if I think students can obtain just as good instruction here as in Europe? That is a little difficult to answer off-hand. I fully believe we have some teachers in America as able as any on the other side; in some ways they are better. For one thing they are morally better—I repeat, morally better. For another they are more thorough: they take more interest in their pupils and will do more for them. When such a teacher is found, he certainly deserves the deep respect and gratitude of the American student. But alas, he seldom experiences the gratitude.

After he has done everything for the pupil—fashioned him into a well-equipped artist, the student is apt to say: ‘Now I will go abroad for lessons with this or that famous European master!’ What is the result? He may never amount to anything—may never be heard of afterward.

On the other hand, I have pupils coming to me, who have been years with some of the greatest foreign masters, yet who are full of faults of all kinds, faults which it takes me years to correct. Some of them come with hard touch, with tense position and condition of arms and body, with faulty pedaling, and with a lack of knowledge of some of the fundamental principles of piano playing.

“How do I teach them to acquire power with little effort? Relaxation is the whole secret. Your arm is really quite heavy, it weighs considerable. Act on this principle then: let the arms fall with their full weight on the keys, and you will have all the power you need, provided the fingers are rounded and firm. That is the other half of the secret. The finger joints must be firm, especially the third joint. It stands to reason there can be no power, no brilliancy when this joint is wavering and wobbling.

“I teach arched hand position, and, for children and beginners, decided finger action; the fingers are to be raised, in the beginning, though not too high. Some teachers may not teach finger action, because they say artists do not use it. But the artist, if questioned, would tell you he had to learn finger action in the beginning. There are so many stages in piano playing. The beginner must raise his fingers in order to acquire finger development and a good, clear touch. In the middle stage he has secured enough finger control to play the same passage with less action, and still perform it with sufficient clearness; while in the more finished stage the passage may be played with scarcely any perceptible motion, so thoroughly do the fingers respond to every mental requirement.

“Sometimes pupils come to me who do not know scales, though they are playing difficult compositions. I insist on a thorough knowledge of scales and arpeggios, and a serious study of Bach. I use almost everything Bach ever wrote for the piano; the Two and Three Part Inventions, French and English Suites, Well-tempered Clavichord, and the organ Preludes and Fugues, arranged by Liszt.”