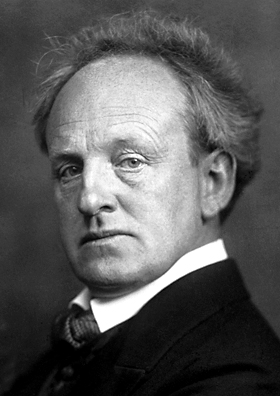

Gerhart Hauptmann (1868-1946).

- Profession: Playwright.

- Residences: Breslau, Berlin.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 15-11-1862 Obersalzbrunn, Poland.

- Died: 06-06-1946 Agnetendorf, Poland.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Island cemetery of cloister, Hiddensee, Germany.

Gerhart Hauptmann was a German dramatist and novelist. He is counted among the most important promoters of literary naturalism, though he integrated other styles into his work as well. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1912. Gerhart Hauptmann was born in 1862 in Obersalzbrunn, now known as Szczawno-Zdrój, in Lower Silesia (then a part of Prussia, now part of Poland). His parents were the Robert and Marie Hauptmann, who ran a hotel in the area. As a youth, Hauptmann had a reputation of being loose with the truth. Beginning in 1868, he attended the village school and then, in 1874, the Realschule in Breslau for which he had only barely passed the qualifying exam. Hauptmann had difficulties adjusting himself to his new surroundings in the city.

He lived, along with his brother Carl, in a somewhat run-down student boarding house before finding lodging with a pastor. He also ran into problems with the Prussian-influenced school. Above all the strictness of the teachers and the better treatment of his noble classmates. His dislike and numerous illness which kept him from attending class, led to his having to repeat his first year. Over time, he came to appreciate Breslau because of the opportunity to visit the theater.

In the spring of 1878, Hauptmann left the Realschule to learn agriculture on his uncle’s farm in Lohnig (today ?agiewniki ?redzkie in Gmina Udanin, Poland). After a year and a half, however, he had to break off his training. He was not physically prepared for the work and he had a contracted a life-threatening lung ailment that troubled him for the next twenty months.

After he failed to pass an officer entry exam for the Prussian Army, Hauptmann entered the sculpture school at the Royal Art and Vocational School in Breslau in 1880. There he met Josef Block who became a lifelong friend. After a temporary expulsion, due to “poor behavior and insufficient diligence,” and a quick reinstatement at the recommendation of sculptor and Professor Robert Härtel, Hauptmann left the school in 1882. For his brother’s wedding, he wrote a short play, Liebesfrühling, that was performed on the night before the wedding. Also at the wedding, he met the bride’s sister, Marie Thienemann. He secretly became engaged to her and Marie began supporting him financially, which enabled him to begin a semester of studying philosophy and literary history at the University of Jena, which he soon quit.

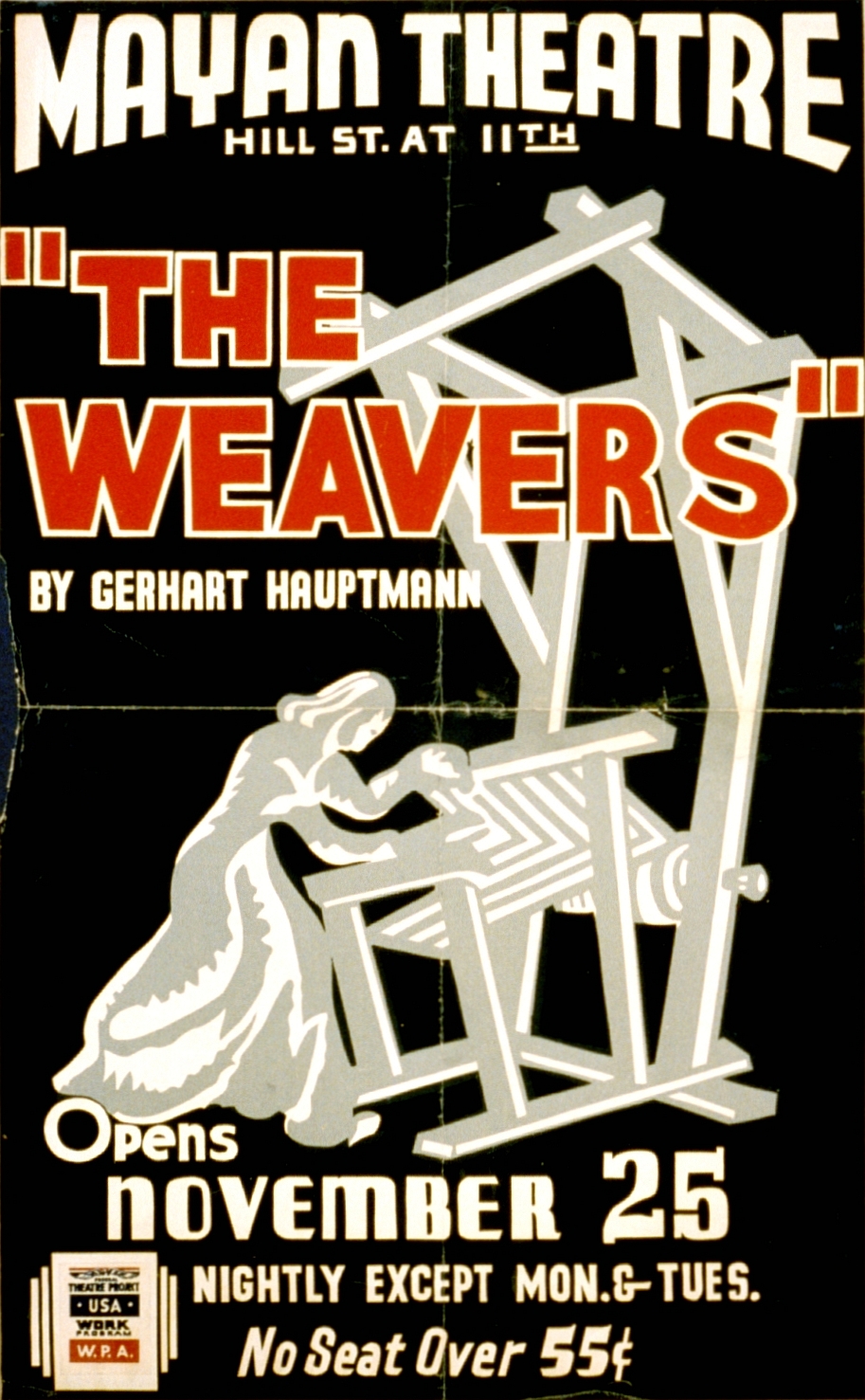

After he left Jena, Marie financed a Mediterranean trip, which he undertook with his brother Carl. On the trip, he decided to settle in Rome as a sculptor, however he had little success. His attempt to establish himself as part of Rome’s German expatriate community also failed and his large clay sculpture of a German warrior collapsed. Hauptmann returned to Germany, disappointed and began a brief stint at the Royal Academy in Dresden before beginning to study history at Humboldt University of Berlin. While there, he devoted his interests to the theater rather than to his studies. In 1891 he moved to Schreiberhau in Silesia. It was followed by The Reconciliation (1890), Lonely People (1891) and The Weavers (1892), a powerful drama depicting the uprising of the Silesian weavers in 1844 for which he is best known outside of Germany.

Hauptmann married Marie Theienemann in Radebeul on May 5, 1885. In July, they took their honeymoon to Rügen along with Carl and his wife, Marie’s sister, Martha. They visited the island of Hiddensee, which would become a favorite retreat of Hauptmann’s. Because the city air bothered Gerhart’s lungs, the couple spent the first four years of their marriage in the town of Erkner where their three sons were born. In 1889, they moved to Charlottenburg in Berlin. There he joined the naturalist literary club “Durch,” which included among others Karl Bleibtreu and Wilhelm Bölsche.

During this period he began to write. His first work was a “novelistic study” Signalman Thiel in 1888. His first play, Before Sunrise, was first staged in 1889, directed by Otto Brahm. It inaugurated the naturalistic movement in modern German literature. It was followed by The Reconciliation (1890), Lonely People (1891) and The Weavers (1892), a powerful drama depicting the rising of the Silesian weavers in 1844 for which he is best known outside of Germany. His work also included comedies, including Colleague Crampton (1891) and The Beaver Coat (1893).

In 1893, he also took actress Margarete Marschalk as his lover. In order to get some distance, Marie moved to the US with their sons. Hauptmann prepared the first French performance of his play The Assumption of Hannele and then went after Marie, without even staying for the premiere. The rift, however, was not to be bridged. After several years of separation, the marriage was ended in July, 1904. However, Marie continued to live in the villa Hauptmann had built in Dresden.

From 1901, Hauptmann lived with Margarete Marschalk in Agnetendorf (today Jagni?tków in Poland). He called it “the mystical protective sheathing of my soul.” In the preceding year, Margarete had born him a son, Benvenuto. In September, 1904, they were married; this second marriage lasted until his death, though it was thrown into a serious crisis in 1905 and 1906 by his affair with a 16-year-old actress, Ida Orloff.

In 1910, Hauptmann’s first novel was published, The Fool in Christ, Emanuel Quint, which told the story of a wandering preacher who mixed sun worship and Christianity together. His 1912 novel, Atlantis became the basis for a Danish silent film of the same name. The novel was written one month before the RMS Titanic disaster, and the film’s 1913 release was less than one year after the event. The storyline for both involved a romance aboard a doomed ocean liner, and the similarity to the disaster became obvious. This coincidental untimeliness caused the film to be banned in Norway due to perceived insensitivity. Nevertheless, excited by the possibilities of this new medium, Hauptmann wrote several screenplays (e.g. Appolonius of Tyre), none of which was ever filmed.

Around the turn of the century, Hauptmann began to receive official recognition. Three times he was awarded the Austrian Franz-Grillparzer-Preis. He also received honorary doctorates from Worcester College at Oxford in 1905 and from the University of Leipzig in 1909. In 1912, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature “primarily in recognition of his fruitful, varied and outstanding production in the realm of dramatic art.”

Kaiser Wilhelm II, however, did not care for the “social democratic” poet. He vetoed the awarding of the 1896 Schiller Preis (for The Assumption of Hannele) and at the instigation of his son, Crown Prince Wilhelm, in 1913, a Breslau production of Hauptmann’s play Commemoration Masque (Festspiel in deutschen Reimen) was canceled, because in it the hundredth anniversary of the Liberation of Germany from Napoleon was depicted with a pacifistic rather than patriotic or jingoistic tone. However, the very same Hauptmann who had criticized militarism in the Masque, the very next year was among those who supported the war. Hauptmann signed the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, a manifesto signed by 93 German scientists, scholars and artists, declaring their unequivocal support of German military actions at the beginning of World War I.

Hauptmann also published supportive poems (many of which read as unintentional satires and which he later crossed out in the manuscript). In 1915, Wilhelm II awarded him the Order of the Red Eagle, Fourth Class. After Germany’s military defeat and the fall of the monarchy, Hauptmann fled to the pacifist colony Monte Verità in near Locarno, Switzerland. Several years later, he wrote Till Eulenspiegel, a poetic memorial to Hans Paasche, the pacifist and reformer who was assassinated by ultra-nationalists.