- Profession: Composer.

- Residences: Prague, Vienna, Leipzig, Brno.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 03-07-1854 Hukvaldy, Czech Republic.

- Died: 12-08-1928 Ostrava, Czech Republic.

- Buried: Central Cemetery, Brno, Czech Republic. Just of the main walkway.

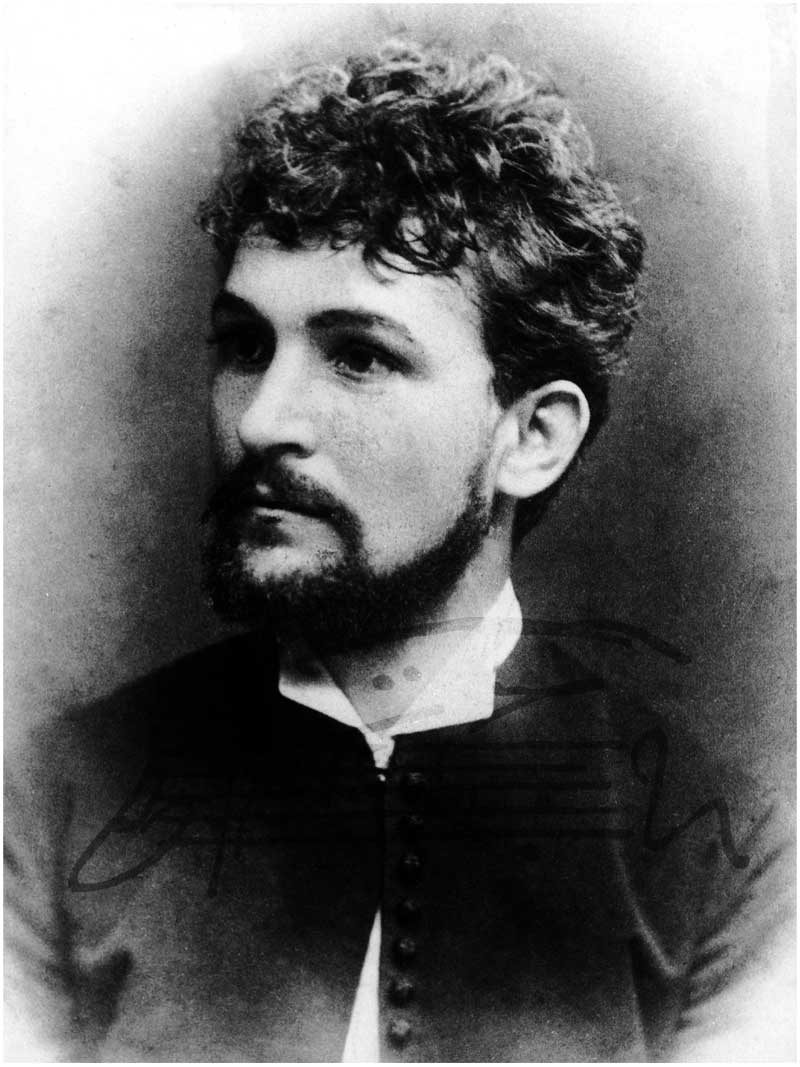

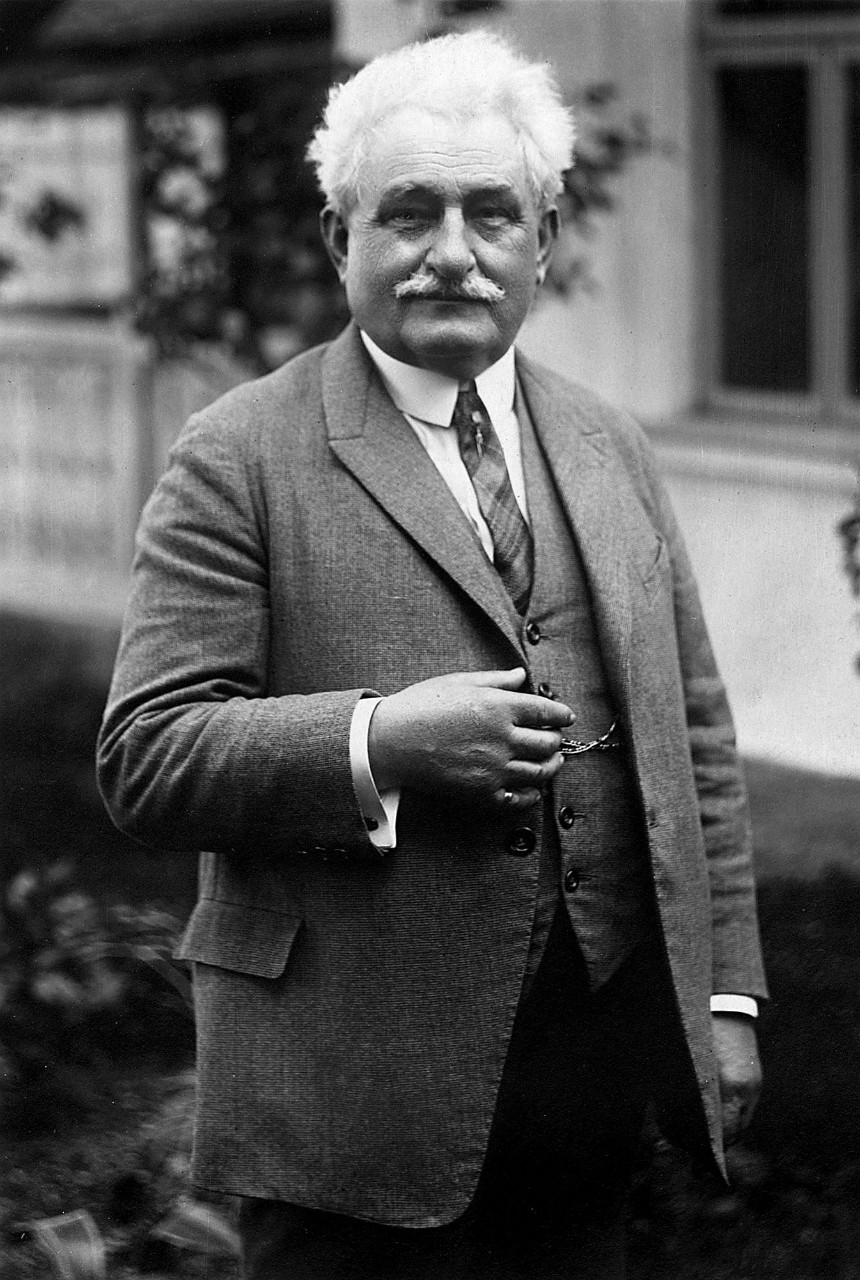

Leoš Eugen Janáček (Janacek) was a Czech composer, musical theorist, folklorist, publicist and teacher. He was inspired by Moravian and other Slavic folk music to create an original, modern musical style. Until 1895 he devoted himself mainly to folkloristic research and his early musical output was influenced by contemporaries such as Antonín Dvorák. His later, mature works incorporate his earlier studies of national folk music in a modern, highly original synthesis, first evident in the opera Jenufa, which was premiered in 1904 in Brno. The success of Jenufa (often called the “Moravian national opera”) at Prague in 1916 gave Janáček access to the world’s great opera stages. Janáček´s later works are his most celebrated.

They include operas such as Kátya Kabanová and The Cunning Little Vixen, the Sinfonietta, the Glagolitic Mass, the rhapsody Taras Bulba, two string quartets, and other chamber works. Along with Antonín Dvorák and Bedrich Smetana, he is considered one of the most important Czech composers.

Leoš Janáček, son of schoolmaster Jiří Janáček (1815–1866) and Amalie (née Grulichová) Janácková (1819–1884), was born in Hukvaldy, Moravia (then part of the Austrian Empire). He was a gifted child in a family of limited means, and showed an early musical talent in choral singing. His father wanted him to follow the family tradition, and become a teacher, but deferred to Janáček’s obvious musical abilities. In 1865 young Janáček enrolled as a ward of the foundation of the Abbey of St. Thomas in Brno, where he took part in choral singing under Pavel Krížkovský and occasionally played the organ.

One of his classmates, František Neumann, later described Janáček as an “excellent pianist, who played Beethoven symphonies perfectly in a piano duet with a classmate, under Krížkovský’s supervision”. Krížkovský found him a problematic and wayward student but recommended his entry to the Prague Organ School. Janáček later remembered Krížkovský as a great conductor and teacher.

Janáček originally intended to study piano and organ but eventually devoted himself to composition. He wrote his first vocal compositions while choirmaster of the Svatopluk Artisan’s Association (1873–76). In 1874 he enrolled at the Prague organ school, under František Skuherský and František Blažek. His student days in Prague were impoverished; with no piano in his room, he had to make do with a keyboard drawn on his tabletop. His criticism of Skuherský’s performance of the Gregorian mass was published in the March 1875 edition of the journal Cecilie and led to his expulsion from the school – but Skuherský relented, and on 24 July 1875 Janáček graduated with the best results in his class. On his return to Brno he earned a living as a music teacher, and conducted various amateur choirs.

From 1876 he taught music at Brno’s Teachers Institute. Among his pupils there was Zdenka Schulzová, daughter of Emilian Schulz, the Institute director. She was later to be Janáček’s wife. In 1876 he also became a piano student of Amálie Wickenhauserová-Nerudová, with whom he co-organized chamber concertos and performed in concerts over the next two years. In February 1876, he was voted choirmaster of the Beseda brn?nská Philharmonic Society. Apart from an interruption from 1879 to 1881, he remained its choirmaster and conductor until 1888.

From October 1879 to February 1880 he studied piano, organ, and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory. While there, he composed Thema con variazioni for piano in B flat, subtitled Zdenka’s Variations. Dissatisfied with his teachers (among them Oscar Paul and Leo Grill), and denied a studentship with Camille Saint-Saëns in Paris, Janáček moved on to the Vienna Conservatory, where from April to June 1880 he studied composition with Franz Krenn. He concealed his opposition to Krenn’s neo-romanticism, but he quit Josef Dachs’s classes and further piano study when he was criticised for his piano style and technique. He submitted a violin sonata (now lost) to a Vienna Conservatory competition, but the judges rejected it as “too academic”. Janáček left the conservatory in June 1880, disappointed despite Franz Krenn’s very complimentary personal report. He returned to Brno where on 13 July 1881, he married his young pupil Zdenka Schulzová.

In 1881,Janáček founded and was appointed director of the organ school, and held this post until 1919, when the school became the Brno Conservatory. In the mid-1880s Janáček began composing more systematically. Among other works, he created the Four male-voice choruses (1886), dedicated to Antonín Dvo?ák, and his first opera, Šárka (1887–88). During this period he began to collect and study folk music, songs and dances. In the early months of 1887 he sharply criticized the comic opera The Bridegrooms, by Czech composer Karel Kova?ovic, in a Hudební listy journal review: “Which melody stuck in your mind? Which motif? Is this dramatic opera? No, I would write on the poster: ‘Comedy performed together with music’, since the music and the libretto aren’t connected to each other”. Janáček’s review apparently led to mutual dislike and later professional difficulties when Kova?ovic, as director of the National Theatre in Prague, refused to stage Janáček’s opera Jen?fa.

From the early 1890s, Janáček led the mainstream of folklorist activity in Moravia and Silesia, using a repertoire of folksongs and dances in orchestral and piano arrangements. Most of his achievements in this field were published in 1899–1901 though his interest in folklore would be lifelong. His compositional work was still influenced by the declamatory, dramatic style of Smetana and Dvo?ák. He expressed very negative opinions on German neo-classicism and especially on Wagner in the Hudební listy journal, which he founded in 1884. The death of his second child, Vladimír, in 1890 was followed by an attempted opera, Beginning of the Romance (1891) and the cantata Amarus (1897).

In the first decade of the 20th century Janáček composed choral church music including Ot?enáš (Our Father, 1901), Constitutes (1903) and Ave Maria (1904). In 1901 the first part of his piano cycle On an Overgrown Path was published, and gradually became one of his most frequently performed works. In 1902 Janáček visited Russia twice. On the first occasion he took his daughter Olga to St Petersburg, where she stayed to study Russian. Only three months later, he returned to St Petersburg with his wife because Olga was very ill. They took her back to Brno, but her health was worsening. Janáček expressed his painful feelings for his daughter in a new work, his opera Jen?fa, in which the suffering of his daughter became Jen?fa’s.

When Olga died in February 1903, Janáček dedicated Jen?fa to her memory. The opera was performed in Brno in 1904, with reasonable success, but Janáček felt this was no more than a provincial achievement. He aspired to recognition by the more influential Prague opera, but Jen?fa was refused there (twelve years passed before its first performance in Prague). Dejected and emotionally exhausted, Janáček went to Luha?ovice spa to recover. There he met Kamila Urválková, whose love story supplied the theme for his next opera, Osud (Destiny).

In 1905 Janáček attended a demonstration in support of a Czech university in Brno, where the violent death of František Pavlík (a young joiner) at the hands of the police inspired his 1. X. 1905 piano sonata. The incident led him to further promote the anti-German and anti-Austrian ethos of the Russian Circle, which he had co-founded in 1897 and which would be officially banned by the Austrian police in 1915. In 1906 he approached the Czech poet Petr Bezru?, with whom he later collaborated, composing several choral works based on Bezru?’s poetry. These included Kantor Halfar (1906), Mary?ka Magdónova (1908), and Sedmdesát tisíc (1909). Janáček’s life in the first decade of the 20th century was complicated by personal and professional difficulties. He still yearned for artistic recognition from Prague.

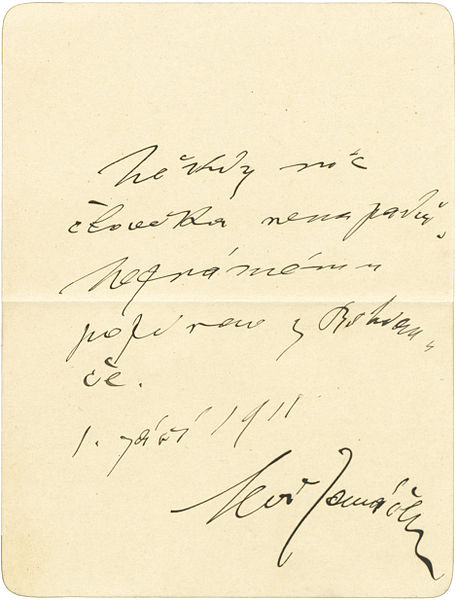

Leos Janacek (1854-1928) “Manchmal fällt dem Menschen nichts ein. Dem Unbekannten ein Gruß aus Bohdanec.” (01-09-1911).

He destroyed some of his works – others remained unfinished. Nevertheless, he continued composing, and would create several remarkable choral, chamber, orchestral and operatic works, the most notable being the 1914 Cantata V??né evangelium (The Eternal Gospel), Pohádka (Fairy tale) for cello and piano (1910), the 1912 piano cycle V mlhách (In the Mist) and his first symphonic poem Šuma?ovo dít? (A Fiddler’s Child). His fifth opera, Výlet pana Brou?ka do m?síce, composed from 1908 to 1917, has been characterized as the most “purely Czech in subject and treatment” of all of Janáček’s operas.

In 1916 he started a long professional and personal relationship with theatre critic, dramatist and translator Max Brod. In the same year Jen?fa, revised by Kova?ovic, was finally accepted by the National Theatre; its performance in Prague (1916) was a great success, and brought Janáček his first acclaim. He was 62. Following the Prague première, he began a relationship with singer Gabriela Horváthová, which led to his wife Zdenka’s attempted suicide and their “informal” divorce. A year later (1917) he met Kamila Stösslová, a young married woman 38 years his junior, who was to inspire him for the remaining years of his life. He conducted an obsessive and (on his side at least) passionate correspondence with her, of nearly 730 letters. From 1917 to 1919, deeply inspired by Stösslová, he composed The Diary of One Who Disappeared. As he completed its final revision, he began his next ‘Kamila’ work, the opera Ká?a Kabanová.

In 1920 Janáček retired from his post as director of the Brno Conservatory, but continued to teach until 1925. In 1921 he attended a lecture by the Indian philosopher-poet Rabindranath Tagore, and used a Tagore poem as the basis for the chorus The Wandering Madman (1922). At the same time he encountered the microtonal works of Alois Hába. In the early 1920s Janáček completed his opera The Cunning Little Vixen, which had been inspired by a serialized novella in the newspaper Lidové noviny.

In Janáček’s 70th year (1924) his biography was published by Max Brod, and he was interviewed by Olin Downes for The New York Times. In 1925 he retired from teaching, but continued composing and was awarded the first honorary doctorate to be given by Masaryk University in Brno. In the spring of 1926 he created his Sinfonietta, a monumental orchestral work, which rapidly gained wide critical acclaim.

In the same year he went to England at the invitation of Rosa Newmarch. A number of his works were performed in London, including his first string quartet, the wind sextet Youth, and his violin sonata. Shortly after, and still in 1926, he started to compose a setting to an Old Church Slavonic text. The result was the large-scale orchestral Glagolitic Mass. Janáček was an atheist, and critical of the organised Church, but religious themes appear frequently in his work. The Glagolitic Mass was partly inspired by the suggestion by a clerical friend, and partly by Janáček’s wish to celebrate the anniversary of Czechoslovak independence.

In 1927 – the year of the Sinfonietta’s first performances in New York, Berlin and Brno – he began to compose his final operatic work, From the House of the Dead, the third Act of which was found on his desk after his death. In January 1928 he began his second string quartet, the Intimate Letters, his “manifesto on love”. Meanwhile, the Sinfonietta was performed in London, Vienna and Dresden. In his later years,Janáček became an international celebrity. He became a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1927, along with Arnold Schoenberg and Paul Hindemith. His operas and other works were finally performed at the world stages.

In August 1928 he took an excursion to Štramberk with Kamila Stösslová and her son Otto, but caught a chill, which developed into pneumonia. He died on 12 August 1928 in Ostrava, at the sanatorium of Dr. L. Klein. He was given a large public funeral that included music from the last scene of his Cunning Little Vixen, and was buried in the Field of Honour at the Central Cemetery, Brno.