Cyclical connections with earlier movements that appear in the final movement are more extensive and more subtly integrated into the symphonies content than in any symphonic movement Mahler had written previously, rather than merely quoting or even paraphrasing themes or motives from earlier movements, Mahler reworks them into new thematic and motivic material, while retaining the rhythmic and cordial motives of fate that bind the entire Symphony together.

The rhythmic fate motive is pounded out on the timpani with brute force, while the Major to Minor chordal fate motive is powerfully stated by the brass evoking the tragic fate of the hero. The rhythmic fate motive appeared in the first and second movements, laying the groundwork for the hammer blows of fate that fell the hero in the finale, the chordal fate motive appeared at the close of the first movements first subject at the corresponding point in the recapitulation at the end of the scherzo, and appears at the beginning of the finale, reinforcing the prophecy of doom that hovers over the entire symphony.

Integration of the introductory material into the Sonata structure in Rondo like fashion, recalls a similar procedure used in the first movement of the Third Symphony, where the opening horn call not strictly part of the exposition, returns at the beginning of the recapitulation.

The use of three principal subjects in the exposition has precedents in Bruckner symphonies, but in the finale of Mahler’s sixth, they correspond to the first movement themes. Even the main exposition tempo of both movements is essentially the same Allegro energy code. The usual order of subjects in the recapitulation is reversed here, as it is in the first movement. Although the third subject opens the recapitulation, as it does in the first movement. The first subject soon reappears and gradually takes over.

Another deviation from standard Sonata practice is the reprise of the first theme group in the Mediant minor, C minor instead of A minor. Also, neither the chorale theme that recalls the first movements brass Chorale, nor the second subject that is a distorted version of the motive of redemption, or ever recapitulated.

In its extraordinary length and complexity, the development section takes on a new significance. As Robert Samuels points out, it no longer functions as a dynamic antithesis to static basic relationships. But here it becomes the battlefield, in which a cataclysmic conflagration ensues between opposing forces brought together from earlier movements. Three times during the development, the music surges ahead in waves striving to reach a climax, only to be crushed by hammer blows of fate.

In a quasi narrative analysis, the exposition presents a dramatic persona, opposing forces personified as individual thematic subjects, even more than in the fifth symphony, frequent tempo shifts, unusual key modulations and complex thematic transformations can make it difficult to grasp this enormous movement. Wide intervals distort the thematic material, and leaping octaves within themes. Recall the importance of octave leaps and other movements.

The veiled German six chord with which the movement begins, creates an aura of mystery, anticipated with much greater force and the orchestral outburst before the scherzo’s coda. Constantin Floros suggests that Mahler’s use of motives has a quasar impressionistic quality. He envisions the entire movement as operating on two different levels. As he says, “one is unreal, dreamlike and far removed, the other is in the foreground and real”.

Clipped dotted rhythms from the first two movements return and permeate the main argument of the finale. These dotted rhythms give a martial quality to the march that carries the opposing forces into battle. Unlike the first movement that ends with a dynamic surge of A major, the minor tonality prevails here, enveloping the music and gloom and desolation just before the final pronouncement of fate. Three fateful hearables the last of which fells the hero have enormous impact, the first to virtually divide the central part of the movement into a tripartite substructure. Mahler eliminated the last of the hammer blows after the premiere. Until recently, most commentators including Alma Mahler, claimed that Mahler had made this decision because of his superstitious fear that it might portend his own death. Erwin Rohde claims that Mahler eliminated the third hammer stroke, because, as he put it, “it exaggerated the feeling of an ultimate ending, which actually is no ending” on the contrary, Redlich contends that Mahler wanted to reinstate the third stroke, but did not have time to have yet another revised version of the symphony published.

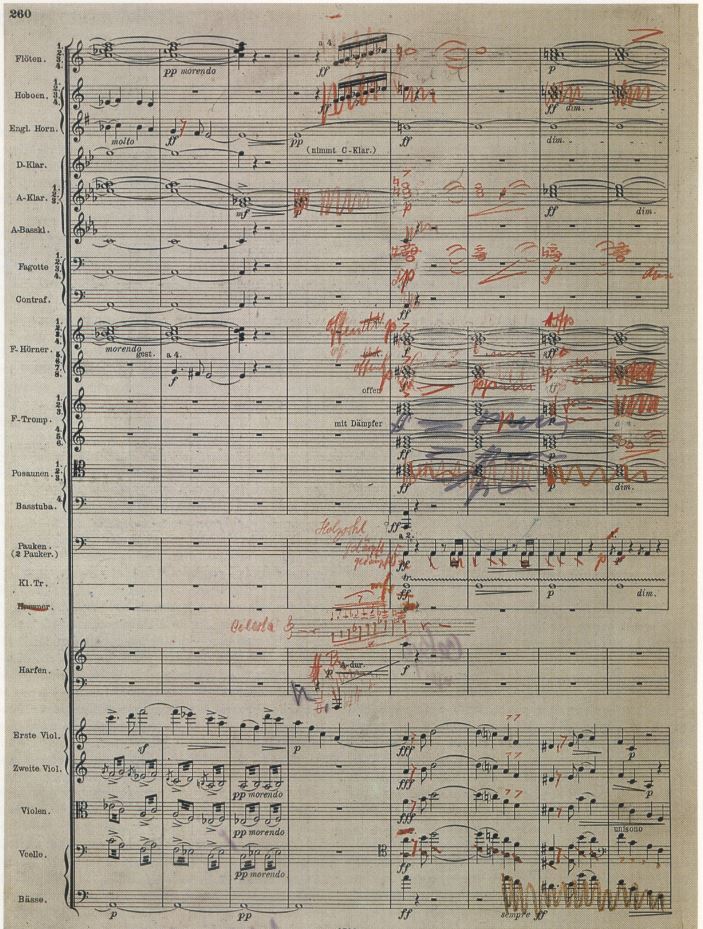

The Mahler Gizelle Sharp’s critical edition of the score, edited by rocks, substitutes and ascending glissando in celestia, harp and flute, as a lead in to the measure in which the third hammer blow appeared in the first published edition. Several conductors, including Leonard Bernstein, on the recording that we’ve chosen to post, have included the third hammer stroke in their recorded performances, but confuse the issue by retaining the rest of the revised orchestration at the place where the hammer is reinserted.

Since the third hammer blow is not an essential musical element, and unlike the others appears not at a climax but in the midst of the reprise of the introduction before the clock the coda begins. It has little impact on the musical structure.

Richard Strauss always the showman could not understand why the hammer strokes became progressively weaker, he felt that an opportunity to heighten the drama was thereby missed. It is likely that Mahler chose to make each succeeding stroke less powerful than the previous one, to symbolize the gradual weakening of the hero and his resolve to fight on. It is interesting to note that the Ritter poem upon which Strauss based his Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) refers to hammer blows of death. Floros connects the six and another Strauss work, suggesting that the symphony is a kind of tragic counterpart of unhealed. Laban the hero’s life, in which tragic annihilation is substituted for heavenly transfiguration. It is not unlikely that Mahler considered the movement and the entire Symphony as his own Hilden Laban and feared that its tragic conclusion might be prophetic of his own end.

Within a year after the premiere, Mahler suffered three blows of fate:

– He lost his first child will fatal illness

– He was diagnosed with what could be a fatal heart disease, and,

– He left his position as music director of the Vienna State Opera, one that he coveted for most of his mature life.

He would never recover from these devastating blows. In a certain sense, Mahler’s terrifying vision of fate is more horrible than death itself. It represents not merely the end of life, but complete oblivion. The meaning of vO Tom’s dreadful realization of finality, when he uttered the words does end at the climax of his monologue in act two of The Valkyrie.

Could all that the hero Mahler, if you will, had accomplished in his lifetime, been for not, despite his conceit that his time will yet come? Might Mahler have feared that his own fate would be the kind of earthly oblivion so touchingly expressed in each been developed abandoned common, but a clickable post mortem or worse, that his works would be misunderstood and abused when he can no longer influence their performance?

Alma tells us how profoundly Mahler related to the symphony, after the final rehearsal for its premiere, she came upon Mahler in his dressing room, bathed in perspiration, pacing up and down in a terrible state of anxiety, wringing his hands and moaning pitifully. He apparently conducted the first performance badly for trying to keep his emotions under control.

If there is so much in the finale that is positive and redeeming, that the brief pronouncement of fate with which it ends seems insufficient to nullify the courageous impulse that drives much of the music in the outer movements. Jacques de 36 suggested that the undaunted strength and courage displayed throughout the finale, even after the second hammer blow, are too substantial to be completely annihilated by the last explosion of A minor and the strokes of fate with which the symphony ends. In an historical approach Redlich exceeds the conclusion has a vision of the end of an era and a portent of the tragic fate of the human race that came terrifyingly close to annihilating itself in the 20th century.

The extensive introductory section can be divided into five sub sections, each of which contains essential thematic and motivic material that will either return intact or as elements of principal themes during the rest of the movement.

The first subsection begins in C Minor, on a soft low C punctuated by a strong pizzicato note in low strings. A mysterious German six chord that tore mon calls a superimposed seventh embellished with rising arpeggios in celestia and harp envelops the atmosphere in a veiled mist, shuttering string tremeloes chill the atmosphere with foreboding. First violins, a certain arden theme that strives upward valiantly from a rising octave, only to fall in accented quarter notes.

The second measure of the violence theme includes the three rising notes of the motive of longing with which the first movements on the theme began. But these notes neither serve as an upbeat to the theme nor resolved downward. Instead, they continue to rise, producing the effect of longing unresolved. The descending part of this theme, portends the dunkel refrain from the first movement of Das Lied von der Erde song to the words dark is life, so is death. The tonic, a minor is firmly established on a strident statement of the third and fourth measures of the striving theme. Theme A we’ll call it, seamless played in horns and strings, accompanied by a powerful pronouncement of both the cordial and rhythmic motives of fate, sinking to the depths of the string ensemble. The first sub section concludes as it began on a mysterious low C.

The second sub section of the introduction, opens with a dark morose theme, we’ll call it theme B. It’s played by the tuba and begins with the rising octave of the striving theme, and continues with a dotted rhythmic figure, motive X, that is a variant of the march beat from the first movement and was used flippantly in the scherzo, it is accompanied by offbeat plucks in the harp, that descending chromatically. Other images from the first and scherzo movements also reappear, such as the 32nd note upbeat in woodwinds, which now resolves into the motive of whoa, we’ll call motive Y, a falling minor second, inversion is added to this second introductory theme, theme B.

Flowing tones on notes of an A minor seventh chord in woodwinds, harp and celestia and tremolo violas from the first movement follow here, recalling the undulating rhythm that permeates the baseline and the third symphonies Nietzsche movement, instead of cowbells, deep bells accompany this music and introduce a horn call will call theme C, based upon the introductory theme B that anticipates the bright third subject of the exposition.

Recollections of the first movement are bound as another horn continues to expand upon elements from both the hero and Alma themes of the first movement. At the same time, low winds present a figure, we’ll call theme D. That has characteristics of the first movements hero theme, and will become part of the expositions first theme.

This figure contains both a dotted rhythm and a rising octave from A and B introductory themes and relates to a phrase from the fifth song of Kindertotenlieder. String tremolo sometimes jumped out of the musical fabric, adding a spectral quality that also recalls the scherzo, isolated musical cells suddenly enter and disappear like phantoms. The celestia brings back the dotted rhythms of the first movement march, the tuba lumbers in with a variant of motive X, the dotted rhythmic figure from the B theme, now ending with a falling octave.

When an oboe defiantly plays the same figure twice as fast following it up with motive Y, horns jump in abruptly with a grotesque paraphrase of the hero’s theme from the first movement, we’ll call this theme Z, which counters the initial upward octave leap with a super octave plunge. This ghastly phrase is actually a distortion of the trial ally march rhythm from the Wunderhorn song Revelge. The isolated dotted rhythm of motive X can also be found and Revelge, the tempo suddenly races ahead as the same sequence of motives just played by tuba and oboe is repeated over continued string tremeloes.

After a brief but even more terrifying outburst of this passage, the tempo calms down on descending dotted rhythms slumping into the base.

The third subsection of the introduction begins as the key changes back to C minor. First low woodwinds and then brass present a dirge like chorale that is reminiscent of the hillside Chorale, from the top or movement of Smith and his mouth lost. The shape of the chorale’s second part relates it to the chorale bridge passage of the first movement, and also to the striving theme that opened the finale, and to the Diaz era chorale from the finale of the Second Symphony. It ends on a full cadence with a powerful statement of the chordal and rhythmic fate motive, all ushered in by the 32nd note upbeat figure of motive Y.

As the tempo presses forward, the fourth subsection of the introduction in G major begins with string tremeloes that recapture the shadowy atmosphere of the opening. A harp plucks out a variant of the preceding chorale while low woodwinds quietly play an elongated version of the single measure motive C that they introduced during the introduction second subsection by adding to this motive arising variant of the dotted rhythm of motive X. The woodwinds begin to piece together what will become the first theme of the exposition. Horns invert this figure anticipating its treatment during the exposition and add to it and accented turn figure from the hillside chorale.

Swelling string tremeloes against pluck tones in the harp introduce the closing section of the introduction. Woodwinds, horns and low strings expand upon various motivic elements from the introduction, particularly lows that anticipate themes of the exposition, such as motives X, Z, and theme D. As the music builds to a climax, the three note upbeat of the Alma theme is added with great force. The fourth subsection ends as the third did, with the rising 32nd note upbeat of motive Y, ushering in another outburst of the chordal fate motive. This time stated even more powerfully than before by the full orchestra, but without the tympani’s rhythmic fate motive.

The tempo quickens to allegro moderato on repeating clip dotted rhythms from the first two movements in the base, thus beginning the fifth and final subsection of the introduction, which also serves as a transition to the exposition. A brisk marching pace is set to a variant of the company’s fate motive, decorated with rising and falling versions of motive Y upbeat, has the repeating dotted rhythms turned into rapid fire 16th notes, the tempo hurries on driving intently toward the exposition, the inverted upbeat of motive Y, and the dotted rhythm of motive X will soon combine into the first theme and impel the music forward to a rapid galope, agitated trumpet tattoos drive the music directly into the expositions first theme.

In basically the same tempo as the first movement, allegro energy Co. The exposition begins immediately with the first principal theme, of which we just heard the beginning at the end of the last excerpt.

Its assertive bravado and driving energy recall the hero’s theme of the opening movement. Several thematic and motivic figures from the introduction combined to form this theme, the striving themes first two notes are converted from an octave interval to a rising major second, with a second note trill.

The cellular motive X appears both in its original and inverted forms, a string of dotted rhythms gives the theme it’s martial character, and theme D is added in its entirety at the end of the first part. The first movements march tread is disguised in the timpani, glockenspiel and side drum. A demonic element is added by the reappearance of the motive of the devil’s dance from the first two movements

Mahler begins to develop the first theme immediately after its initial statement, inverting and overlapping its elements in a fascinating variety of permutations, representing fate as the underlying theme of the movement, march like eighth’s in the trombone turned the harmony from Major to Minor as the tempo becomes wait here for the entrance of the second theme, based upon motivic figures from the introduction, horns strongly assert this strange theme that combines a distorted version of the octaves contained in motive C, with the ascending scale from the striving theme, set against the continuation of the dot and rhythms of the march like phrase from the first theme. This rather morbid second theme functions in opposition to the first like an antagonist bent on destroying its enemy.

As with the first theme, the second is developed immediately after its first statement, principally by inversion, juxtaposed against variants of the original that emphasize wide intervalic leaps, winds hint at the introductions Husar chorale, also a possible source of the second theme, relentlessly forceful and assertive. These two principal themes are interconnected and developed in the full orchestra. The rising upbeat of motive Y and the bass ushers in a brief rhythmic segment that sounds like a Shostakóvich in gallop, giving the impression of a charge into battle, and recalling the rapid marches in the first and second movements.

Mahler will recycle this music for us in the first movement of the Seventh Symphony, as the strings continue with swirling 16th note figuration, a trumpet and trombone play the defiant theme D in canonic imitation, after which low woodwinds and brass play its inversion. Soon the music softens its zeal and fierceness gradually dissipating.

Unexpectedly the tonality modulates to D major, and a third principal theme appears quietly in first horn against repeating triplets and woodwinds. Based upon theme C from the introduction, this sunny new theme contrasts markedly with the dark aura and riveting intensity of the first two themes. It expresses the hero’s confidence in his mission to overcome the negative impulses exposed in the first two movements. He or the third theme sounds much like a clarion call to victory. In addition to a reference to the introductory themes C, it contains several other elements from the introduction, some of which already appeared in the first theme, such as the clip dotted rhythms of motive X. In an inverted form sourced in theme D, an excerpt from the first theme appears here in woodwinds caught up in the resilience of the third theme. Violins offer an exhilarating counter theme, based upon the first theme combined with the first part of the third theme, high strings over harp arpeggios, rhapsodize on the third theme, as the music pleads for redemption.

But that please cut short abruptly by the return of the clip dotted march rhythms, now more agitated than before. With this unanticipated switch from the soaring lyricism of the violins counter theme to the stridency of the march rhythm, we enter the closing section of the exposition. Trumpets bring back the third theme and variation, while violins ardently assert their counter theme, and horns add a note of defiance on motive Z from the second theme. Moving forward aggressively these elements combine as the exposition comes to a close, they seem to stumble into the development on a falling octave wail on all eight horns with bells held upward without any transition. The german six chord with which the movement began returns, this time in D minor, to usher in a capsulated reprise of the introduction. The violin striving theme now falls instead of rising, and cellos and basses treated in canonic imitation, its ardent yearning having been diffused gradually the tempo slows as the music from the introduction is reintroduced in a different order than originally, the tuba plays an augmented version of theme D sounding ever more mysterious than before, cowbells, string tremeloes and harp and chillest chords accompany fragmentary motives from the introductions second subsection over a sustained D pedal in low strings. The rising 30 seconds of motive Y are inverted and the first horn gives a ghost like aura to a falling phrase from the expositions first theme. Trumpet and trombone quietly begin the third subsection with the introductory themes C, recalling the sunlight of the expositions third principle theme, as if from afar. Woodwinds echo the brass with an augmented variant of the last measure of theme C, the music seems to be enveloped in a night missed, sounding veiled and mysterious. Suddenly, the clip dotted rhythms of the march figure that impel the music forward during the bridge passage to the exposition. Now brusquely intrude upon the quiet scene, woodwinds cry out against fate, with a moan of whoa, on motive Y, from the introductions second subsection in a dialogue with bass march rhythms. On their last woeful cry of distress, the woodwinds hold on to the top note over a diminished sixth chord in D that resolves to a bright F sharp major chord. This chordal harmonic shift prepares the way for the return of the expositions assertive third theme in horns against two warning cries of motive Y.

After the third theme tries to reassert itself, motive Y breaks in with its ominous portent of inevitable tragedy. During this passage, Mahler’s harmonic creativity is clearly an evidence. Although he begins the reprise of the third theme and F sharp major, the horns play it in B flat, then the subsequent return of motive Y shifts the harmonic underpinning to match the tonality of the third theme through the use of a diminished sixth chord. Undaunted by these auguries of fate, woodwinds returned with the romantic counter theme that first appeared in high violins sweeping away all thoughts of tragedy in a rhapsodic outpouring by the entire orchestra, embellished with harp, arpeggios. Rising octaves reinforced the heroes courage and fortitude. The introduction striving theme combines with a third subjects counter theme to become one. A trumpet call rises above the orchestra on an elongated version of the tail end of theme C, that recalls the Otello fragment that appeared in the finale of the Third Symphony.

As ascending and descending scales from the gloomy hillside chorale of the introductions third subsection work their way into the musical fabric. Accented quarter note triplets replace eighth’s in the first theme, making it sound even more emphatic, profuse polyphony of thematic and motivic material evolves during this extensive development of the first subject. Music of tremendous assertiveness and vitality continues unabated for nearly 50 measures. But then negative elements invade, falling octaves contradict the rising octaves of the first subject. Elements from the second subject enter, bringing with them descending chromatics that produce a fearful sense of foreboding tension increases as the music becomes more and more terrifying as it builds to a climax on the third subjects counter theme. At the height of this enormous buildup, horns and trumpets assert a variant of the third theme, intending to go on developing the music’s heroic character but instead of rising, the variant falls and is cut off by an overpowering hammer stroke.

Mahler directs that this gigantic blow should not sound metallic, but like the stroke of an axe. It both aborts the mounting climax before it reaches closure and shatters the heroic music that seems so indestructible during the preceding section. It should not go on notice that the two measures that precede the hammer blow not only present a variant of a phrase from the third theme, but also contain an elongated version of the first two notes of the first theme.

This first hammer blow coming in the midst of a dramatic buildup creates a terrific shock that sends the hero wildly spinning in all directions. It virtually slashes the development in twain, momentarily freezing the music in stark terror.

Trumpets defiantly assert an augmented version of part of the first theme, while trombone simultaneously thunder out the second theme in inverted augmentations, making it even more evident that the latter is what the underside of the former strings enter one measure after the blow in a rapid tempo with wild dotted rhythmic figures reminiscent of the scherzo with its mocking transformation of the heroes march rhythm from the first movement, this figuration then alternates with frantic 16th Note runs that propelled the music forward with great urgency. D minor tonality adds an ominous note to the turbulent agitation that follows. Trumpets and trombones set the chorale theme against the second theme in a terrifying presentment of death. After different sections of the orchestra forcefully assert the clip dotted rhythmic figure from the chorale, it is finally stated with great power in high woodwinds and violins. Trumpets bring back the third theme that sounds like a diminutive version of the chorale, when juxtaposed against it.

The aggressive force asserted during this entire passage gives an impression of the defiance of the hero against the devastating blow struck by the antagonist. Suddenly, the tonality changes to a vibrant A major on waves of broken chord triplets in low strings, and a descending scale in horns. The tempo calms down as strings ascend with a phrase that combines the scalar elements of the introductions striving theme with a transfigured version of the expositions third theme on trumpets and trombones over waves of harp arpeggios.

Despite the destructive force of the first hammer blow, we sense that victory may still be snatched from the throes of defeat. But when the key reverts to F minor, the intensity and agitation that followed the first stroke returns, motives X and Y combine and integrate with elements of the first theme, a turbulent battle rages on an expanded treatment of the Shostakóvich and galloping rhythms that ushered in the exposition. This time, the full orchestra urges the music onward with a sequence of rising trills. This furious music comes to a complete stop, and violent whiplash is strike out from the silence, followed by an attack of pounding, clipped dotted rhythms on the timpani, against a canonic volley of the rising and falling version of the upward thrusting sixteenths of motive Y and the major to minor corral fate motive.

When the key changes to C minor with major key overtones, the timpani is clipped dotted rhythms continue in the bass against a steady beat set by the horns and reads the router, establishing a strong march TRID akin to that of the first movement, motives X and Y combined to form a new thematic conjunction. As the next segment of the development section begins, the heroes strengthened valor seems undiminished despite the traumatic shock of the first hammer blow. As the march continues to develop, undergoing various permutations and combinations of the motive combination X-Y, Mahler reverses the position of X and Y and as one measure of the darted march rhythm, to forge yet another thematic variant representing the valley and character the hero who has apparently come through the first stage of the battle unscathed. Horns echo the third theme against the violins more embellished version. Let’s listen from the development of the march music.

After various sections of the orchestra take turns with a new heroic theme motive X-Y. Motive X falls by an octave transforming the new theme motive set against the phrase from the second part of the first theme in trombones. When the key shifts to G major horns enter above the new heroic theme with the morrow second theme. It’s malevolence given a grotesque quality by octave and super octave leaps and dives, trombones threatened with menacing chromaticism.

Galloping rhythms return to add impulse to the increasing agitation as another battle between the first and second themes begins. Motive Y disengages from the new heroic theme, which soon disappears to serve as either a rising or falling upbeat for these two principal themes. Just as this second encounter gets started, violins lift the orchestra out of the foray, elevating the music to a higher plane in a resplendent A major, on the partially inverted version of the striving theme that opened the development, the music calms down as a brief state of equilibrium is established. But the fact that the striving theme descends rather than asons from its rising octave, is a sign that the second conflict has already caused the heroes of injury. Just as unexpectedly as it arose, the uplifting music fades as the tempo continues to hold back.

English horns and second, violins enter quietly with an inverted version of the first theme, imbued with a pail on earthly light, says Delamar. The theme now projects a menacing quality as it slowly rises from the depths and builds to a climax that portends a catastrophe, as before the first hammer stroke. Now, however, the reconfigured third theme has a deathly aura. The second of the two rising notes that hinted at the first theme, just before the first stroke fell, is no longer trill, thus losing its vibrancy. At the height of an abbreviated orchestral build up, the expected climax is shattered by the terrifying thud of the second hammer stroke. Not only does the stroke market change of key to D minor, but serves to further split the development. Although reinforced by symbols in tam-tam and mark fortissimo instead of fortissimo as before, this second hammer blow does not seem to severely diminish the hero strength. Instead of becoming disheartened, the hero reacts to the blow as if it were a signal to return to battle. The first and second themes engage each other, their combat propelled forward by torrents of rapid 16th note string figuration.

Soon the gloomy hillside chorale descends over this fateful struggle as the pace quickens, the chorales kinship with the second theme makes them allies, as both seem to overwhelm the heroic first theme. For an all too brief moment, the spiritually uplifting segment that interrupted the battle earlier tries to intercede but it’s rising and falling octaves are set upon by fragments of the clip dotted rhythm through the mark, an indication that the heroes antagonist is gaining the upper hand this tortured version of what was once an image of great striving and courage. Now strains shed itself of the negative effects of the second stroke of fate as the music presses forward urgently. One sense is that the hero hurls himself against the enemy, with all the strength that he can muster. Two rapid but powerful strokes in the full orchestra rise to what could be the final blow, just as the first two notes of the first theme did twice before, as the development abruptly comes to an end. Instead of a third blow, the mysterious german sixth core that opened the movement veils the music in a ghostly haze. Muted brass enhance the mystical power of the strange chord. As at the opening, this cord is followed by a sequence of rising string tremeloes, this time only briefly extended.

Mahler creates an unusual effect by quietly sustaining a dissonant de pedal, even while the striving theme and C minor, the key in which the movement began enters forcefully in first violins. As it continues, the rising theme begins to lose its strength and immediately diminishes evidence of the effect of a conflict upon the hero’s spirit.

Sounding no less Urian pretentious and abbreviated and slightly reorcastrated reprise of the introduction follows omitting old but its first two subsections, horns no longer support violins on the extension of the striving theme that accompany the fate motive first appearance. Even the Major to Minor chord of fate seems somewhat unfocused. Now play it on a reverse swell that gives as much emphasis to the major as to the minor chord. The model rhythm that accompanies this chordal sequence is played with more brutality than when first heard on the timpani during the opening of the introduction.

After the return of a foreboding second subsection, with its menacing bass, descending chromatics and darting and flickering sounds, cowbells accompany the shimmering chords that embellish themes C, stated by a pair of horns, a lonely oboe, and then a horn can only produce a faint glimmer of the bright third theme. In fact, this joyous theme, Mark grazioso ushers in the recapitulation, not the first theme, as in traditional sonata form, an oboes plays it softly, but with a sprightly air, and the solo violin then gently intones the after theme, reminding us of its relationship to the first movements Alma’s theme of falling phrase from this theme that just introduced the reprise of the third theme is itself a precursor of the delicate third subject of Nachtmusik II from the Seventh Symphony.

After elements of the third theme have developed briefly, an inverted version of the second themes leaping octaves appears in the bass against the second part of the third theme in the violins. That theme now builds to a climax, giving the impression of impending victory. With a powerful broaden statement, played by the full brass choir with added timpani flourish. Just as the third theme reaches for climax, the music abruptly comes to a halt, and the clip dotted march rhythm returns in a rapid tempo. A fragment from the third theme hastens forward intently in the violins, as if urging the hero into battle. Without warning, the battle resumes just when the hero would seem to have proclaimed victory. tonality quickly shifts to a dynamic A major, the hero enters the foray on the third theme, driven forward by swirling 16th note figuration alternating with ascending and descending clip dotted rhythms, revitalized to what would appear to be full strength. The hero fights on courageously, but in the midst of a fierce combat. The timpani remind him of the inevitable end by hammering out the dreaded rhythmic fate motive. At the same time, the ugly image of a second theme appears in trombones like a hideous specter. Let’s listen from where the music approaches what seems like the hero’s victory

As the tempo continues to move forward with increasing intensity, two trumpets powerfully assert the heroic first theme. It joins with its positive counterpart, the third theme, fighting furiously against an enemy that does not seem of equal strength during the struggle. That the three principal themes are not really independent, but different aspects of the hero becomes increasingly apparent as their respective elements engage in contrapuntal interplay, paralleling the relationship between the principal themes of the first movement. Once again, the music rises to a climax, but it fails to materialize. Instead, the first theme group returns in the home key of A minor. Its former strength and vitality showing no sign of diminishing the antecedent of the first theme is played in the bass against his consequent in the treble.

Quickly the hero charges into battle on the Shostakóvichien gallop last heard just before the second part of the development, the so called march development. After an inverted version of the first theme, its original form appears in the full orchestra for the first time since the beginning of the exposition. How strong and courageous it sounds here, having lost none of its power, despite the enemy’s violent onslaughts once more brass bellow the tragic cordial fate motive, but its rhythmic counterpart on the timpani now seems slightly less demonstrative. Raging 16th note figuration in strings, based in part on motive Y, and reminiscent of the furious music that followed the hammer strokes accompanies these fateful pronouncements, the grotesque second subject returns to the combat now in low woodwinds and tuba, with the hero represented by a brilliantly conceived integration of elements from both the first and third themes. The striving theme would soon enters on its rising octave, relates to the octaves of the second theme when pitted against a fragment of the third theme and the bass.

Mahler scatters these elements throughout the orchestra in a brilliant display of thematic and motivic polyphony. It should be noted that the music of the recapitulation has been presented at full strength up to this point, despite having begun with an uncharacteristically repressed treatment of the third theme, over 100 measures before. It will continue in this manner until the closing epilogue. More than 100 measures later. The debilitated striving theme that began the development reasserts itself with falling rather than rising eighth’s, it can do nothing to hinder another powerful statement of the fate motive. The battle rages on as the second theme becomes more aggressive. It combines with the hillside chorale, thereby amassing greater strength against the heroic forces with which it is engaged in mortal combat. While the second theme leads the field, the striving theme briefly enters and violins grotesquely transformed into the monstrous second theme, with contorted into VALIC leaps that widen and become more dissonant. At the same time trumpets tried to keep pace with a strengthened a second theme, by asserting a segment of the first theme that appeared during the introduction as theme D. Motive why hails the return of the galloping rhythm that heightens the intensity of his violent combat. The second theme continues to press forward and the brass over torrents of whirling string figuration that had urged this music forward during the second subsection of the development. Violins tried to ascend to a climax out of a raging torrent of string figuration, as they had earlier when they lifted the furiously combative music out of itself, and transported to music to a peaceful playing on the striving theme. However, this time the upsurge of strings brings with it not the positive striving theme, with his yearning for redemption but the twisted second theme, and a chromatic variant of a fragment of the hillside chorale, neither of which could engender a feeling of spiritual uplift. Instead, they symbolize the destruction of all that is heroic in humankind, the negative side of the human spirit with which the positive side has been in combat throughout this enormous movement. The battle rages on as the galloping rhythms reenter for a few measures. After the music of sins seeking a positive outcome to the conflict, it suddenly collapses has the falling tag end of the third theme, and inversion of motive Y breathlessly hastens the hero’s demise along ascending harp glissando leads to the closing section of the recapitulation.

Once again the tempo becomes more agitated, as the striving theme enters willfully in A major, making every effort to change the course of destiny.

Tinged with chromaticism, the chorale now signifies an attempt to corrupt the striving theme, despite his efforts to free itself with canonic twists and turns from the close knit counterpoint of the chorales deadly grasp. Violins enter on the gruesome second theme, octaves from the striving theme rise and fall in overlapping sequence as if uncertain of which way to turn. Then the first and third themes and horns and violins team up, with an inverted version of the striving theme in woodwinds and violas to make one final effort to forestall the heroes tragic fate. As the tension flags, positive forces rest for a moment to regain their strength. Over waves of string arpeggios, the first theme builds gradually in a weighty tempo against an accented descending scale in horns, valiantly the hero tries to clutch victory from the hands of defeat.

On the brink of a climax, the music collapses on a low A, shaken by a strong tam-tam stroke. But didn’t we expect the third hammer blow here at the end of such intense striving? Instead heralded by a mid measured celestia chord, we hear the mystical german sixth chord that opened the movement bursting out in wins with greater power than ever. What a way to start a coda, yet the music that follows is from the introduction, as if we were to be in for yet another round. Shuttering the string tremeloes again rise to usher in the violence striving theme, played with all the strength that has left at the end of the themes long descending phrase that gradually softens, as if unable to find enough strength to finish. Mahler originally inserted his third and final hammer blow, it was to be played less powerfully than either the first two, but strong enough to fill the weakened hero. The impact of this enormous thud combined with the awesome chordal fate motive the timpani is rhythmic fate motive, and the assertive after theme that had not been heard since fate had made its first appearance at the beginning of the movement is devastating.

Mahler later eliminated this third stroke, replaced it with bass drum and tam-tam, followed by a 16th note ascending scale on the celestia that leads into the fate motives. By doing so he toned down the power of this climactic moment without seriously affecting its musical significance. The recording of the symphony used here includes the third hammer blow.

Following the after themes gradual diminuendo, as it slowly descends to the depths of the orchestra, the closing epilogue begin in a measurably slower tempo, dark and cavernous low brass generate an air of mystery, as they softly in tone a doleful chorale, based upon theme C from the second subsection of the introduction, played in canonic imitation, the mournful sound of what was once a vital striving theme, now sapped of its former strength and assertiveness combines with theme C, and falls helplessly as the music trudges along, limping on a broadened version of the dotted march rhythm, also sapped of its former energy, octaves rise and fall ominously, as if called from the beyond. Finally, the music sinks into the silence of a dark abyss, on a low A minor chord. Out of the depths come the morose tones of theme B, which began the second subsidiary section of the introduction. It’s dotted rhythm is repeated twice a slowly, symbolic of complete resignation to tragic fate. These gloomy sounds sink into the depths and die away to what appears to be an eternity of silence. But just as we seem to come to the end, the entire orchestra suddenly explodes on an enormous A minor chord, to which the timpani pronounces the final sentence of doom, to merciless strokes of the rhythmic fate motive. It is extended by a few grace noted strokes that die away slowly. After one last breath, the movement ends quietly with a single pizzicato note. Neville Cardus described this last note, as like the sound of the last clump of Earth, tossed onto a coffin. Live, sound and fury ends, not with a bang, but with a whimper.

There can be little doubt of Mahler’s intentions here. His hero meets a tragic end, it is also our end, and the tragedy of it is our tragedy. It is not the inevitability of death that is the real tragedy here, but that the hero succumbs to an antagonist that is his own self destructive side. In the fifth symphony, Mahler confronted the dread of death by looking outward into the wellspring of life, examining its positive and negative characteristics and absorbing them into himself in an effort to overcome the destructive effects of the fear of death. In the sixth, the problem is viewed from an internal rather than external perspective. But in confronting his inner self, the hero cannot avoid his own dark side, and he’s ultimately and inevitably destroyed by it. Thus, the tragic fate of humankind is not that life must end in death, but that we may not have the ability to conquer our own negativity.