Helsinki (Helsingfors, Helsinge fors, i.e. Helsinge Rapids, Stadi, Helsset)

When a town was founded in Forsby village in 1548 it was named Helsinge fors, i.e. Helsinge Rapids. The name refers to the Vanhankaupunginkoski rapids at the mouth of the river. The town was commonly known as Helsinge or Helsing, from which the Finnish name Helsinki developed.

The name Helsinki has been used in Finnish official documents and in Finnish language newspapers since 1819, when the Senate of Finland moved to Helsinki from Turku (Swedish: Åbo). The decrees issued in Helsinki were dated with Helsinki as the place of issue. This is how the form Helsinki came to be used in written Finnish. As part of the Grand Duchy of Finland in the Russian Empire, Helsinki was known as Gelsingfors in Russian.

In Helsinki slang the city is called Stadi (from the Swedish word stad, meaning “city”). Hesa (short for Helsinki), is not used by natives to the city. Helsset is the Northern Sami name of Helsinki.

Helsinki was established as a trading town by King Gustav I of Sweden in 1550 as the town of Helsingfors, which he intended to be a rival to the Hanseatic city of Reval (today known as Tallinn). Little came of the plans as Helsinki remained a tiny town plagued by poverty, wars, and diseases. The plague of 1710 killed the greater part of the inhabitants of Helsinki.

The construction of the naval fortress Sveaborg (In Finnish Viapori, today also Suomenlinna) in the 18th century helped improve Helsinki’s status, but it was not until Russia defeated Sweden in the Finnish War and annexed Finland as the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland in 1809 that the town began to develop into a substantial city. During the war, Russians besieged the Sveaborg fortress, and about one quarter of the town was destroyed in an 1808 fire.

Russian Emperor Alexander I of Russia moved the Finnish capital from Turku to Helsinki in 1812 to reduce Swedish influence in Finland, and to bring the capital closer to St Petersburg. Following the Great Fire of Turku in 1827, The Royal Academy of Turku, at the time the country’s only university, was also relocated to Helsinki, and eventually became the modern University of Helsinki.

The move consolidated the city’s new role and helped set it on a path of continuous growth. This transformation is highly apparent in the downtown core, which was rebuilt in neoclassical style to resemble St Petersburg, mostly to a plan by the German-born architect C. L. Engel. As elsewhere, technological advancements such as railroads and industrialization were key factors behind the city’s growth.

Gustav Mahler

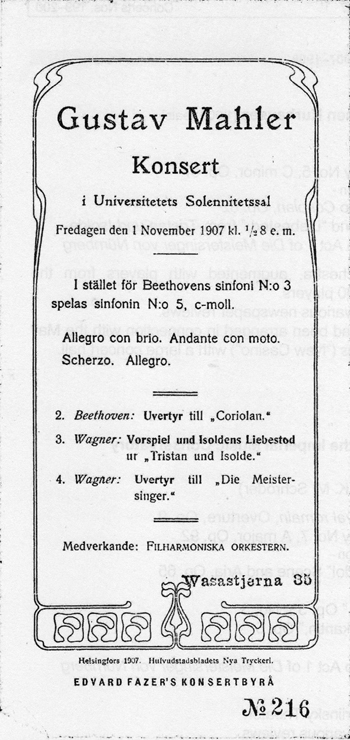

His visit to Helsinki formed one element in an extended tour lasting from 19 October to 12 November to the Russian empire (within which, from 1809–1917, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy. It was his last such journey while Director and it has been comprehensively documented by Henry-Louis de La Grange. On this trip Mahler conducted twice in St Petersburg, and once in Helsinki (1907 Concert Helsinki 01-11-1907), but he performed his own music (the Fifth Symphony) only in St Petersburg (on 9 November).

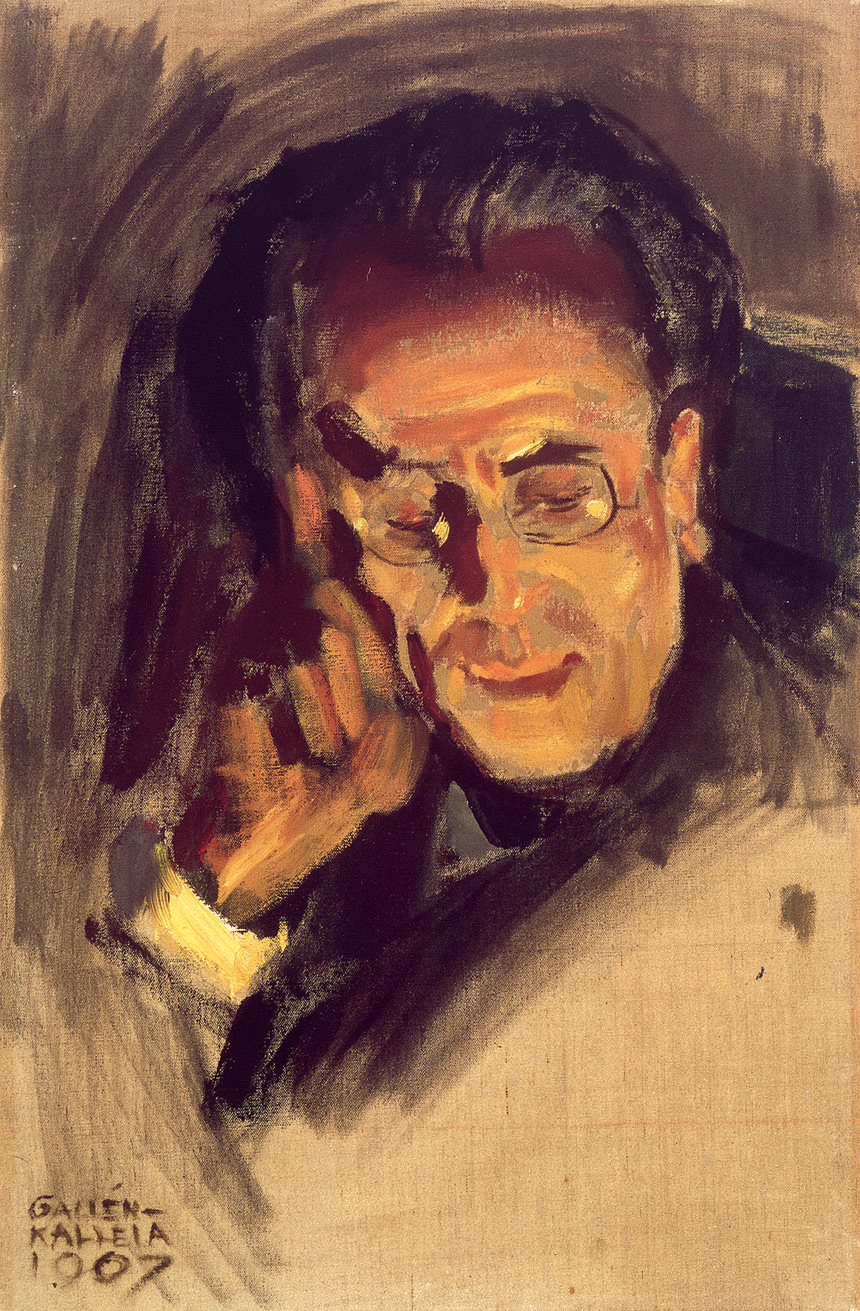

However, if the visit to Helsinki did not directly contribute to the dissemination of his works in Finland, it offered Mahler an opportunity for personal and musical contacts. He not only met Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) more than once, but also the conductor and composer Robert Kajanus, with whom he got on rather well, and who he heard perform works by Sibelius (Valse triste and Vårsång, op. 16) and Josef Suk (Fantastické scherzo, op. 25); he was also able renew the acquaintance of the artist, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931).

Akseli Gallen-Kallela

They had first met in early 1904, at the time of the Nineteenth Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, at which Gallen-Kallela had a number of works on display, and were presumably introduced by either Carl Julius Rudolf Moll (1861-1945) or Alfred Roller (1864-1935) (Head of Stage Design at the Court Opera), both of whom, as members of the Secession, were in correspondence with their Finnish colleague.

In turn, it was through Gallen-Kallela that Mahler met in Helsinki the architect Eliel Saarinen (1873-1950) and visited Hvitträsk, the house – ‘more a castle really’, according to Mahler – built by Saarinen with his two partners, Herman Gesellius, and Armas Lindgren. Interestingly Mahler immediately made comparisons with Viennese architectural trends, describing it as ‘very much à la [Josef] Hoffmann … like a Finnish Hohe Warte’.

Although Mahler had not promoted his own music, his brief visit attracted an enormous amount of press coverage, and ensured that his career continued to attract attention in Finland even after his departure from his preeminent position in Vienna. So it was an, at the time relatively little-known singer, with (apparently) only one Mahler song in her repertoire, who introduced Mahler’s music to wider musical circles within and beyond the capital.

Year 1907. Gustav Mahler. Oil paining by Akseli Gallen-Kallela. Just after this painting was completed, Mahler wrote about it to his wife, Alma: ‘When it got dusk, we sat in the twilight in front of the open fire, where huge logs blazed and glowed as though in a smithy. Gallen, who had kept his eyes fixed on me throughout the trip in the most singular way (as if he’d spottted a hare), suddenly set up an easel and began on my portrait. Lit up only by fire, quite a la Rembrandt…. An hour passed: I had to go and was just bidding them all farewell when my host brought the easel along and there, to the wonder of all, was my portrait – completely finished. Very fine as a painting and also a strong likeness. You would be astonished!’.

Dagmar Hagelberg-Raekallio

Dagmar Hagelberg-Raekallio (née Sarlin; 1871–1948) was born in the small central Finnish town of Viitasaari, was trained as a singer in Viborg/Viipuri and Paris, but seems not to have developed any significant public performing career until her thirties. In the event this was relatively short-lived as a thyroid operation damaged her vocal chords. Nevertheless, Hagelberg-Raekallio deserves a secure place in Finnish performance history for having been perhaps the first singer to perform foreign-language songs in Finnish, a controversial strategy in a bilingual country.

The aim was ostensibly to promote a better understanding of the text among listeners who were unfamiliar with French, Italian or German, but inevitably the practice invited accusations of nationalism. Hagelberg-Raekallio’s concert in Helsinki on 16 November 1907 adopted this strategy, with translations of songs by Schubert, Mendelssohn and Chopin appearing alongside Finnish songs, but comprehensive details of the programme seem not to have been published in the press.