Image: 1903. ‘Amsterdam’ by George Breitner (1857-1923).

Introduction

In the autumn of 1903, Gustav Mahler stepped off the train at Amsterdam’s Central Station with high hopes. He had been invited by Willem Mengelberg, the young phenomenon who had transformed the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra into an ensemble of international standing. What began as a single visit to conduct his Third Symphony would evolve into one of the most fruitful artistic partnerships in classical music history.

Over the course of five visits between 1903 and 1910, Mahler found something precious in Amsterdam: a musical home where his revolutionary symphonies were not just performed, but truly understood. While other European cities remained skeptical of his innovations, Amsterdam’s audiences listened with rare attention, and Mengelberg prepared the orchestra with an obsessive dedication that astonished even the demanding composer. The collaboration between these two men—along with the exceptional musicians of the Concertgebouw Orchestra—would establish a tradition of Mahler performance that continues to this day.

text below by: Jan Brokken

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) visits to the Netherlands:

Visit 1 to the Netherlands: 19-10-1903 until 26-10-1903:

- Amsterdam: Amsterdam railway station, City of Amsterdam, Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO), House Willem Mengelberg, Beurs van Berlage, Port of Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, House Hendrik Jan de Marez Oyens.

- Zaandam: City of Zaandam, Czar Peter House.

- The Hague: City of The Hague, Scheveningen.

- Haarlem: City of Haarlem, Zandvoort.

Visit 2 to the Netherlands: 19-10-1904 until 28-10-1904:

- Amsterdam: Amsterdam railway station, City of Amsterdam, Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO), House Willem Mengelberg, House Hendrik Jan de Marez Oyens, House Boissevain, House Diepenbrock, Hotel American.

- Haarlem: City of Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum.

- Hilversum: Train Amsterdam – Hilversum (v.v.), Hilversum railway station, Gooische steamtram, City of Hilversum.

- Laren: City of Laren, Gooische steamtram, Saar de Swart (1861-1951), Villa De Hoeve.

Visit 3 to the Netherlands: 06-03-1906 until 11-03-1906:

- Amsterdam: Amsterdam railway station, City of Amsterdam, Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO), House Willem Mengelberg, House Diepenbrock, Rembrandt House, Beurs van Berlage, Jewish Broad Street, Restaurant Van Laar.

- Valkeveen: City of Valkeveen, Gooische steamtram, Zuiderzee. Photos 08-03-1906.

- Naarden: City of Naarden, Gooische steamtram, House Boissevain Drafna.

- Laren: City of Laren, Gooische steamtram, Moors between Hilversum and Laren. Photos 10-03-1906.

Visit 4 to the Netherlands: 27-09-1909 until 08-10-1909:

- Amsterdam: Amsterdam railway station, City of Amsterdam, Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO), House Willem Mengelberg.

- The Hague: City of The Hague, Hotel Le Vieux Doelen, Building of Arts and Science.

Visit 5 to the Netherlands (Incognito): 26-08-1910 until 28-08-1910:

Map Gustav Mahler himself in the Netherlands (1903, 1904, 1906, 1909 and 1910).

Gustav Mahler in Amsterdam

In October Year 1909, following the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra’s Dutch premiere of his Seventh Symphony – which he’d conducted himself – Mahler came down with a terrible cold. Waiting for the train at Central Station, he ran out of handkerchiefs and had to cadge two off Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921). Shortly before the express left for Vienna, Mahler asked his composing colleague how he could stand living in a city where, ‘it always rains and there’s so much noise.’ Despite his almost physical aversion – he shuttered whenever he uttered the word Amsterdam – the city would go down in history as Mahler’s second musical home.

Mahler’s fondness for Amsterdam had little to do with the city itself. He wasn’t one to spend his afternoons strolling along the canals or the Amstel river, he wasn’t enchanted by the gabled facades reflected in the gently rippling water. Amsterdam’s mysterious halftones didn’t inspire him to create enigmatic sounds. In fact, the hustle and bustle of the harbours and quays was too much for him. He preferred to flee the city whenever possible, to the dunes at Zandvoort or the heath near Naarden.

It seems that Mahler was deeply impressed by his visit to the Rijksmuseum, and was particularly touched by Rembrandt’s portraits, but you almost have to ask yourself: who isn’t? He paused for a long moment in front of the Night Watch, which would later influence the two Nachtmusik movements of his Seventh Symphony; movements full of impressions, not that you’d immediately think: ah yes, that’s Amsterdam. The march tempo of the first Nachtmusik may be a good match for Rembrandt’s militia preparing to move out, but the music’s mood remains unmistakably Viennese.

The Mengelberg Phenomenon

In the autumn of 1903, when Mahler first set foot on Dutch soil, he arrived with high hopes. That was because of the man who – less than a year earlier, on 09-06-1902 during a music festival in Krefeld, Germany – had invited him to Amsterdam: Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951). Mengelberg was considered a phenomenon because of his illustrious beginnings – as Music Director in the city of Lucerne, Switzerland, and, from the age of twenty-four, as chief conductor of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Mahler was known as a hothead with despotic tendencies, at least whenever he was holding a conductor’s baton and felt dissatisfied with the musicians’ efforts.

Mengelberg, a somewhat pompous but jovial younger man, possessed qualities that were unmistakably brilliant: he could play almost all the orchestral instruments and was – not unimportant to Mahler – also an excellent choir conductor. He had managed, in just a few short years, to pull the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO) out of the provincial mud and raise it to an international standard. Quite an achievement, considering that as a musical metropolis, Amsterdam was still a work in progress.

Mengelberg had invited Mahler to conduct his Third Symphony in Amsterdam, and during a subsequent concert, the First. Mahler jumped at the chance, especially since Mengelberg had promised to thoroughly rehearse the works with the orchestra beforehand. That was no mean feat, especially for the Third Symphony. Not just because of the work’s extraordinary length, the size of its women’s choir and the even-larger boys choir, with a mezzo-soprano thrown in for good measure. More than anything, the work was in every respect new, almost alarmingly so.

- Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) Composer.

- Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Conductor and Composer.

- Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) Conductor.

- Mathilde Mengelberg-Wubbe (1875-1943) Wife of Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) (3.)

- Hilda Gerarda de Booy-Boissevain (1877-1975) Daughter of Charles Boissevain (1842-1927). Wife of Hendrik (Han Henri) de Booy (1867-1964) (the photographer).

- Petronella Johanna Boissevain (1881-1956). Daughter of Charles Boissevain (1842-1927). Not yet married.

- Maria Barbera Boissevain-Pijnappel (1870-1950). Married to Charles Ernest Henri Boissevain (1868-1940), who is the son of Charles Boissevain (1842-1927). Her husband is a brother of Hilda Gerarda de Booy-Boissevain (1877-1975) (5.) and Petronella Johanna Boissevain (1881-1956) (6.)

The fascination with Mahler

The world premiere of Mahler’s Third Symphony took place in June 1902 in Krefeld, Germany, so when Mengelberg invited the composer to Amsterdam, the ink on the score was hardly dry. Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) was already familiar with Mahler’s First and Second symphonies, but only on paper. He heard Mahler’s music live for the first time during that premiere in Krefeld. For Mengelberg, Mahler the conductor was almost more impressive than the music itself. Mengelberg was instantly taken by the fascinating power emanating from him:

‘His interpretation, his technical approach to the orchestra, and his way of phrasing and structuring, seemed to me – as a young conductor – to approach an ideal. So by the time I (…) met him personally, I had already been deeply moved by his music.’

In that music, Mengelberg recognised a new form of artistic expression, and it seemed best to invite the composer to Amsterdam to introduce it personally. Mengelberg had previously given other composers the opportunity to conduct their own works in Amsterdam; he was happy to defer to Richard Strauss or Edvard Grieg, or even the likes of Charles Villiers Stanford and other lesser gods. Before those composers began their first rehearsals, Mengelberg had already rehearsed the score systematically with the orchestra. With Mahler’s Third, he went above and beyond, because he feared a ‘Mahleresque scène.’ Mahler was known as a hothead with despotic tendencies, at least whenever he was holding a conductor’s baton and felt dissatisfied with the musicians’ efforts. And that was almost always the case.

Edam Cheese for breakfast

As for a place to stay, Mahler had been thinking of the Amstel Hotel, but Mengelberg insisted on putting him up in his home (House Willem Mengelberg). That was reason enough for Alma not to accompany her husband to Amsterdam – not then, and not during any of his subsequent visits. Gustav preferred the anonymity of hotels and despised cosiness. He felt embarrassed about accepting favours from friends and colleagues. Would he be reduced to asking Mrs Mengelberg to shine his shoes? The idea horrified him. And he liked to sleep late. Could he show up for breakfast at 10:30?

That didn’t seem to be a problem. As he wrote to Alma Mahler (1879-1964), ‘At half past ten, I was nibbling on a piece of Edam. I haven’t seen much of the city, but I’m staying in a respectable neighbourhood, very close to the Concertgebouw, where I spent the rest of the morning rehearsing.’ Willem and Tilly Mengelberg lived on the Van Eeghenstraat 107. Alma, who surrounded herself with an array of artists ranging from Klimt to Kokoschka, would have been horrified by the interior. Swiss clocks, Delft pottery, mediocre paintings, a lot of glass art with a pious theme – Mengelberg’s father was a sculptor known for religious art and architecture.

As for a place to stay, Mahler had been thinking of the Amstel Hotel, but Mengelberg insisted on putting him up in his home.

Gustav was equally unimpressed, but he had to admit that Mengelberg was a host who put guests at ease and couldn’t be bothered with any highfalutin fuss. Mengelberg was German in a good-natured way – his father and mother came from Cologne – and he spoke the language. With celebrities, he used the same congenial manner he used with his own brothers and sisters. He’d been exposed to some of the music’s greats at an early age.

When he was thirteen, he performed Brahms’ Variations on a theme of Handel on the piano, in the home of family friends in Utrecht, earning him a pat on the back from the composer himself. ‘You understand these matters.’ And while still an undergraduate at the Cologne Conservatory, he once played the chimes, filling in for an unexpectedly absent percussionist during a performance of Don Juan. Richard Strauss was eternally grateful – though still a just a boy, Mengelberg had saved the show.

Not friends

By 1903, Gustav Mahler was already a celebrity, albeit more as a conductor than a composer. From the beginning, Mengelberg had enormous admiration for Mahler. As a composer, he immediately recognised Mahler as the Beethoven of the twentieth century. Yet the story of Mahler and Mengelberg is not about two men who bonded instantly and became best mates. Mahler was much too egocentric for friendship. The only thing that mattered to him was music – his music. His appreciation for Mengelberg only emerged during his first rehearsal with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. ‘Listen to this,’ he wrote excitedly a few hours later to Alma. ‘I couldn’t believe my eyes and ears when they unleashed my Third. It took my breath away. The orchestra is outstanding and very well prepared. I’m curious to hear the choir, it’s reputed to be even better.’

The next rehearsal went just as well, and the third went beyond all expectations. A visit to Zaandam and a walk along the windmills of the Zaanse Schans provided some diversion; Mahler reported in a postcard to Alma that he was even beginning to appreciate the typical Dutch light. But more than anything, it was the final rehearsal that drove Mahler to ecstasy. ‘Yesterday’s dress rehearsal was splendid,’ he wrote to Alma. ‘Two hundred school boys led by their teachers (six in all) bellowing bim-bam, plus a spectacular female choir with one hundred and fifty voices! Stunning orchestra! Much better than in Krefeld. The violins just as beautiful as in Vienna.’

Enthusiastic Amsterdammers

The performance received an extraordinarily good review from Dutch paper the Algemeen Handelsblad and was horribly panned by De Telegraaf. Mahler didn’t care; he had experienced first-hand ‘how the people here are able to listen.’ He couldn’t imagine a better audience. He wrote to Alma the next day, ‘Still thinking about last night. It was sublime. People were uneasy at first, but they warmed up a little after each movement, and once the alto solo began, their enthusiasm slowly grew. The cheering after the final chord was impressive. Everyone said that it was the greatest triumph in living memory.’

Mengelberg had attended all the rehearsals, sometimes in plain sight, but more often half hidden in the back of the hall. He experienced those days as one extended master class, something he would draw on for the rest of his conducting career. He would later say that for musicians, Mahler’s way of interpreting his own music was immensely educational. Mahler kept repeating: ‘What is best in music is not to be found in the notes.’

Mahler wrote to Mengelberg from Vienna, ‘I feel like I have found a second musical homeland in Amsterdam.’

According to Mengelberg, that phrase was at the heart of Mahler’s creations and interpretations, and he never tired of repeating those words and putting them into practice. Two days after the second performance of the Third, Mahler began rehearsing his First Symphony. A more straightforward work, with no soloist or choir; shorter, more traditional and easier to understand. And again, Mahler encountered an enthusiastic orchestra, an orchestra that wanted to learn. Mengelberg had prepared the First down to the finest detail. When Mahler returned home after the performance, he cherished the hope that over time, he would come to rule over a sort of musical island in Amsterdam. From Vienna, he wrote to Mengelberg, ‘I feel like I have found a second musical homeland in Amsterdam.’

Year 1907. Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO) with Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) in the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw.

Revising the score

During 1903-1904 season, in conjunction with Mahler’s performances of the Third and First symphonies, Mengelberg presented an additional four performances of the First Symphony in Amsterdam and The Hague. He went into great detail about everything he’d written in the score of the Third, so in future he could reproduce Mahler’s way of performing the work. In a letter to the composer, Mengelberg pointed out misprints in the score and some illogical leaps in a few passages. He would continue to do that for all the later symphonies Mahler conducted in Amsterdam. Mahler almost never paid attention to criticism. He didn’t care for it. No, instead, he wiped it away as if it was something unpleasant on his hat. This wasn’t arrogance – he was filled with continuous self-doubt – but he wouldn’t allow himself to be thrown off balance in any way.

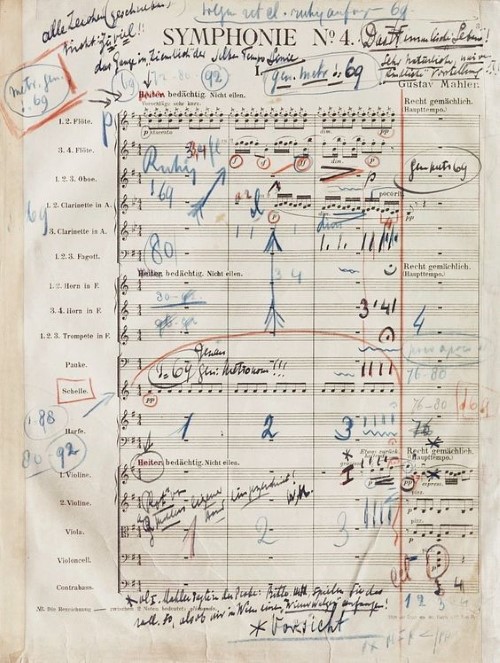

However, Mengelberg’s comments were something he took very seriously because they didn’t just originate from appreciation and admiration of his work, but from a complete oneness with his music. Because he understood Mahler’s method of composing, Mengelberg was able to point out slight omissions and imperfections, problems that could often be resolved with a few minor adjustments. Moreover, Mahler’s working method included making changes to his score if, in practice, he was dissatisfied with the sound. He made changes during every rehearsal and passed them directly on to Mengelberg. These weren’t incidental changes; Mahler wrote hundreds of notes and musical symbols in the score he would conduct from – in the Fourth, there were more than a thousand! Mengelberg would respond to each revision with new suggestions. He became much more than a friend to Mahler. He grew to become a trusted sounding board.

Year 1904. Score Symphony no. 4 with markings from Gustav Mahler and Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951). See 1904 Concert Amsterdam 23-10-1904 – Symphony No. 4 (twice).

The repeat of the Fourth

In 1904, when Mahler returned to Amsterdam to conduct not only his Second, but his brand new Fourth Symphony, he grumbled in a letter to Alma that he was once again obliged to stay with the Mengelbergs. But his tone had shifted. ‘The Mengelbergs were waiting eagerly for me at the station and wouldn’t rest until I had agreed to go with them, and so here I am again, just like last year. They are such kind and selfless people.’

Mahler had a rehearsal with the orchestra the evening he arrived. ‘And do you know,’ he wrote Alma, ‘what they’ve done? That Mengelberg is a genius. They’ve put my composition on the programme twice. After the intermission, it starts again at the beginning. What do you say to that?’ It was indeed to a brilliant way to help the audience become familiar with the new work. To this day, Mengelberg’s unique stunt is mentioned in every biography of Mahler to explain why his innovations caught on so much earlier in Amsterdam than in other cities. For decades, Paris wanted to have nothing to do with Mahler; and in Saint Petersburg, both the older Rimsky-Korsakov and the young Stravinsky reacted with a shrug; while in Helsinki, Sibelius seemed interested but had little affinity.

Following the premiere of the Fourth in Amsterdam, Mahler was in raptures about the musicians. ‘The singer – the Dutch Alida Oldenboom-Lutkemann (1869-1932) – sang the solo simply and with stirring emotion, and the orchestra accompanied her with rays of sunshine. It was a painting with a golden backdrop.’ In 1904, Mahler conducted the Fourth twice, and the Second once. Mengelberg had prepared both symphonies so well that Mahler ended one rehearsal early to visit the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem. ‘You’re very well rehearsed’ he told the astonished members of the orchestra.

Modern

Mahler returned to Amsterdam in March 1906 to conduct his Fifth Symphony. This time he chose to stay with the Mengelbergs because rehearsals started at the – in Mahler’s eyes – ungodly hour of nine, but from the Van Eeghenstraat he could be there in no time.

For this performance, he insisted on three rehearsals in the morning and three in the afternoon, because in Mahler’s own words, the Fifth is ‘difficult, very difficult.’ He’d urged Mengelberg to prepare the piece even better than usual and, starting from October 1905, had plagued the conductor with questions and instructions. Mengelberg had hardly begun studying the score when he was forced to send the manuscript back to Vienna because Mahler had decided to insert some major changes.

After the performance on 08-03-1906, the composer concluded that Mengelberg was, in fact, the only one to whom he could confidently entrust his works. ‘Everything excellently rehearsed. Sounds amazing. The orchestra is fantastic, and they appreciate me. This time it wasn’t back-breaking labour but a pleasure,’ he wrote to Alma, failing to mention that the concert had ended somewhat off-key. The five Kindertotenlieder had been programmed after that seventy-minute-long symphony, and for some of the audience, that was too much of a good thing. Entire rows of people stood up and left before the end of the concert. Mahler simply ignored these fringe elements as being part and parcel of all his performances. Some adored him, some reviled him, and others didn’t know what to think – ‘hideous things next to the most exquisite,’ wrote Elsa Diepenbrock (1868-1939) in her diary.

Her husband, Dutch composer Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921), was considerably more impressed, with both the music and the man. ‘Mahler is very straightforward, doesn’t put on airs; what you see is what you get. Good natured, naive, at times childlike, he peers with ghostly eyes from behind a huge pair of crystal eyeglasses. He is modern in every respect. He believes in the future.’ That’s something Mengelberg also admired in Mahler. In 1909, however, nobody was able to hear how Mahler’s music was forecasting the end of the romantic era.

Hotel Mengelberg or America?

Mahler’s connection with Mengelberg – and Amsterdam – grew even stronger when Mahler turned down an invitation from the Residentie Orkest in The Hague to conduct his Sixth Symphony. ‘Because they’re your competition,’ he said in a letter. In the meantime, Mahler had submitted his resignation to the Vienna Hofoper in order to try his luck in New York. He spared no effort in luring Mengelberg to the United States; he wanted to take his trusted sounding board with him across the ocean. ‘It would be so wonderful to know that you were near me.’

Mengelberg didn’t take the bait; in the decades to follow, he would conduct many times in the United States, but never forsaking his Concertgebouw Orchestra. Mahler’s obligations in America restricted his ability to visit Amsterdam. It wasn’t until October 1909 that he again performed a new work in The Concertgebouw – the Seventh. By then he was raving about his stay at ‘Hotel Mengelberg’ on the Van Eeghenstraat. He described it in the guestbook as a place where ‘a poor musician can find a place to call home.’ He had started to see Mengelberg not only as a critical admirer and devoted apostle but a younger version of himself.

Mahler’s innovations caught on much earlier in Amsterdam than in other cities

Mengelberg was also a composer, although he liked to keep it under his hat. Mahler, however, was curious about Mengelberg’s Rembrandt Improvisations and asked to see the score. The influence of Mahler was clearly evident, and Mengelberg soon came to realise that he’d never escape the shadow of his illustrious role model. Mengelberg decided instead to focus on conducting and accepted – in addition to his post in Amsterdam – the job of chief conductor in Frankfurt. Known for his fresh, direct approach, he soon began to surpass Mahler as a conductor. At least, that’s how Mahler viewed things: when he heard Mengelberg conduct Ein Heldenleben (by arch nemesis Richard Strauss) in Rome, he said afterwards: ‘You have converted me to a Hero’s Life.’ Strauss usually got on Mahler’s nerves.

Year 1909. Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) with Dutch colleagues (photographer: W.A. van Leer for “Weekblad voor muziek”):

From left to right:

- Cornelis Dopper (1870-1939) (Second conductor of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO)).

- Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

- Hendrik Freijer (1876-1955) (Administrator of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO)).

- Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) (Principal conductor of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO/KCO).

- Alphons Diepenbrock (1862-1921) (Composer).

Alma’s gift

Back in Amsterdam, Mengelberg had an innovative idea to call attention to the Seventh: he invited the press to one of Mahler’s rehearsals with the orchestra. As a result, the advance notices and reviews of the performance were full of praise. The brilliance of Mengelberg’s efforts became clear a few days later when Mahler conducted the Seventh – with the selfsame Concertgebouw Orchestra – in The Hague. There, the press had not been invited to a rehearsal, and reviews ranged from fair to middling.

For Mahler, Amsterdam was evolving into a combination of Hotel Mengelberg and the musicians of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. Some were more easily won over than others, but ultimately they all became Mahler enthusiasts. When they performed the Seventh, they pulled out all the stops for Mahler the conductor and the composer. That’s why it’s no coincidence that the hand-written manuscript of the Seventh is still in The Concertgebouw’s possession – it was a gift from Alma Mahler. That manuscript – along with Mengelberg’s own obsessively notated copy of the score – helped set the tone for future performance practices of Mahler’s works in Amsterdam. All the subsequent chief conductors of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, from Bernard Haitink to Riccardo Chailly and Mariss Jansons, have gone on to use that very manuscript.

Final respects

Mahler died rather suddenly on 18-05-1911. He was almost fifty-one years old. At the time, Mengelberg was conducting in Turin, Italy, and was unable to attend the funeral in Vienna. Alphons Diepenbrock went in his place. For the rest of his life, Mengelberg spoke of Mahler in the present tense. ‘As Mahler well knows…’ ‘Mahler thinks…’ ‘Here, Mahler makes a clear caesura…’ During orchestra rehearsals, Mengelberg seemed to be in constant contact with his deceased idol.

He truly paid his final respects in May of 1920 with the Mahler Festival 1920 Amsterdam. Mengelberg, who was celebrating his twenty-fifth anniversary as conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra that year, performed the nine completed symphonies, Das klagende Lied, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Kindertotenlieder, Das Lied von van der Erde and the Rückert Lieder – all in just in fifteen days. In attendance were Alma Mahler (who was lodging in the home an aristocratic lady on the Museum Square), and Arnold Schönberg, another of Mengelberg’s protégés. Alma wrote: ‘Arrival in Amsterdam… harbour… ships’ masts… rigging… busy… chilly, overcast sky… In other words: Holland. In the evening, Mahler’s Second in an incomparably beautiful performance.’

It was a unique festival, with only one (less than modest) ambition: ‘Just as Bayreuth has become the model and benchmark for all performances of Wagner’s work, so has Amsterdam been chosen to become the spiritual centre of Mahler’s art.’ The words are from the festival’s organiser, Dr Rudolf Mengelberg (a distant cousin of the conductor). Amsterdam was destined to become the foremost Mahler metropolis. And that – except for one harrowing period in 1941, when Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s trustees bowed to a command from the German occupying forces and stopped performing Mahler’s music – has always been the case. The city belongs to Mahler and Mahler to Amsterdam.

21-05-1920. Mahler Festival 1920 Amsterdam. Memorial plaque. Group of three. Location: Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw, large hall, near entrance left, front of stage. After a speech by Hendrik Freijer (1876-1955), two plaques designed by sculptor Toon Dupuis (1877-1937) (and executed by the firm Begeer) were unveiled with the effigies of Mahler and Mengelberg.

Text by Jan Brokken