- Profession: Tenor, graphic.

- Residences: Naples, London, New York City.

- Relation to Mahler: Worked with Gustav Mahler.

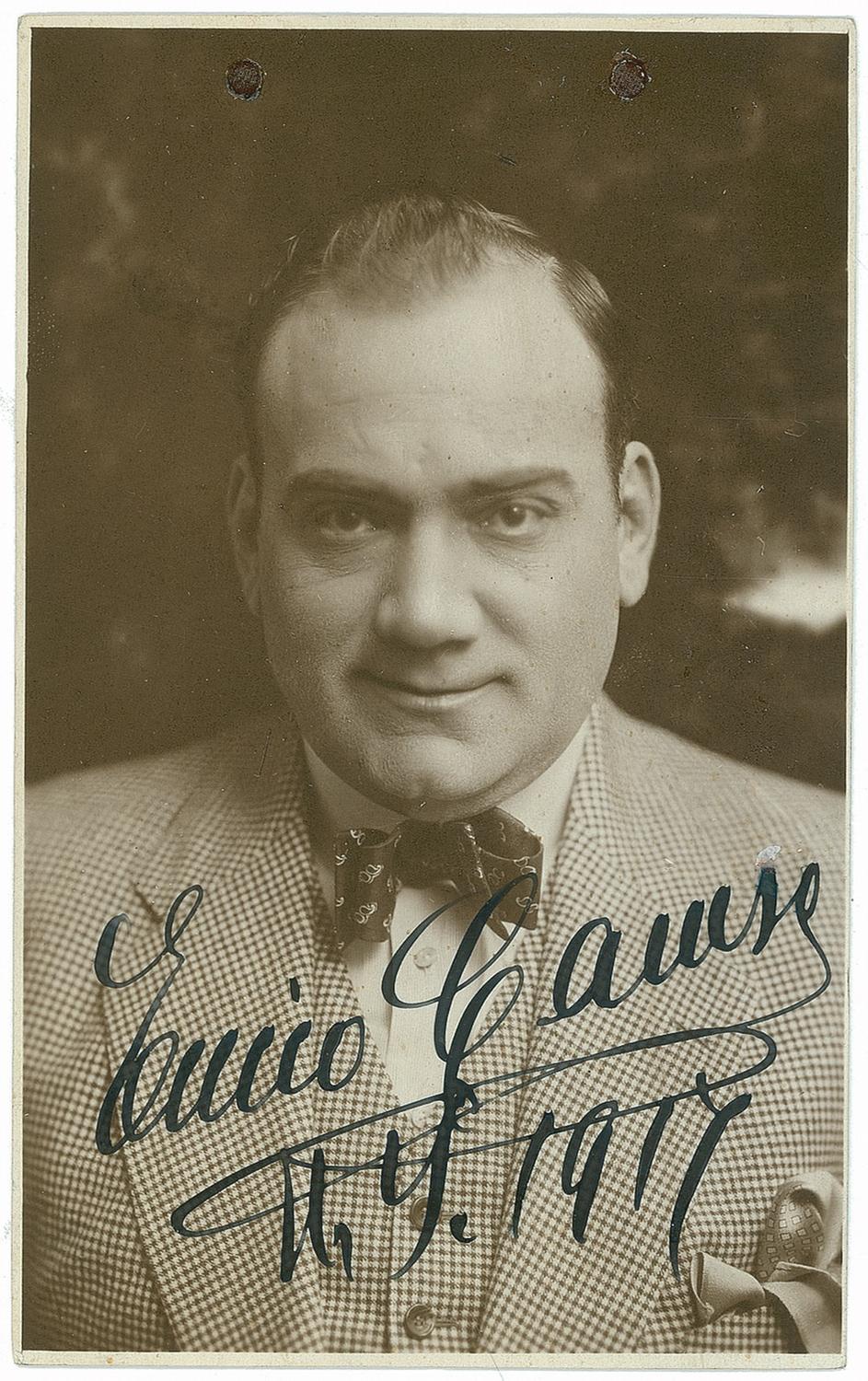

- Correspondence with Mahler: The famous tenor was also a prolific artist noted for his caricatures of musical personalities. See Cartoons and caricatures.

- Born: 25-02-1873 Naples, Via San Giovannello agli Ottocalli 7, Italy.

- Died: 02-08-1921 Naples, Italy.

- Buried: Cimitero di Santa Maria del Pianto, Naples, Italy.

- Opera. No performance together with Gustav Mahler in America.

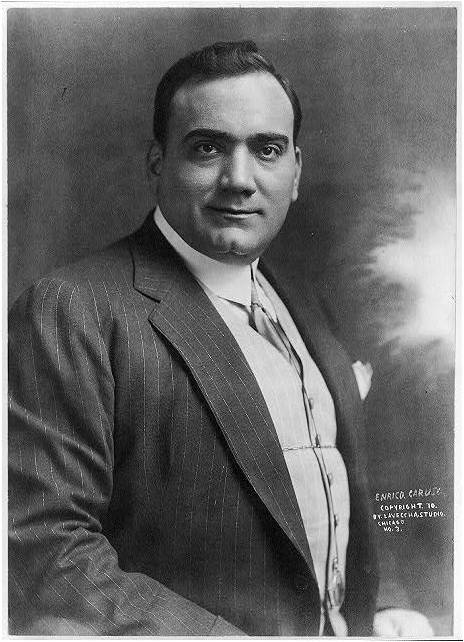

Enrico Caruso was an Italian operatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles from the Italian and French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the dramatic. Caruso also made approximately 290 commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920. All of these recordings, which span most of his stage career, are available today on CDs and as digital downloads.

Early life

Enrico Caruso came from a poor but not destitute background. Born in Naples in the Via San Giovannello agli Ottocalli 7 on February 25, 1873, he was baptized the next day in the adjacent Church of San Giovanni e Paolo. Called Errico in accordance with the Neapolitan dialect, he would later adopt the formal Italian version of his given name, Enrico (the equivalent of “Henry” in English). This change came at the suggestion of a singing teacher, Guglielmo Vergine, with whom he began lessons at the age of 16.

Caruso was the third of seven children and one of only three to survive infancy. There is a story of Caruso’s parents having had 21 children, 18 of whom died in infancy. However, on the basis of genealogical research (amongst others conducted by Caruso family friend Guido D’Onoforio), biographers Pierre Key, Francis Robinson, and Enrico Caruso Jr. & Andrew Farkas,have proven this to be an urban legend. Caruso himself and his brother Giovanni may have been the source of the exaggerated number. Caruso’s widow Dorothy also included the story in a memoir that she wrote about her husband. She quotes the tenor, speaking of his mother, Anna Caruso (née Baldini): “She had twenty-one children. Twenty boys and one girl – too many. I am number nineteen boy.”

Caruso’s father, Marcellino, was a mechanic and foundry worker. Initially, Marcellino thought his son should adopt the same trade, and at the age of 11, the boy was apprenticed to a mechanical engineer named Palmieri who constructed public water fountains. (Whenever visiting Naples in future years, Caruso liked to point out a fountain that he had helped to install.) Caruso later worked alongside his father at the Meuricoffre factory in Naples. At his mother’s insistence, he also attended school for a time, receiving a basic education under the tutelage of a local priest. He learned to write in a handsome script and studied technical draftsmanship. During this period he sang in his church choir, and his voice showed enough promise for him to contemplate a possible career in music.

Caruso was encouraged in his early musical ambitions by his mother, who died in 1888. To raise cash for his family, he found work as a street singer in Naples and performed at cafes and soirees. Aged 18, he used the fees he had earned by singing at an Italian resort to buy his first pair of new shoes. His progress as a paid entertainer was interrupted, however, by 45 days of compulsory military service. He completed this in 1894, resuming his voice lessons with Vergine upon discharge from the army.

Early career

At the age of 22, Caruso made his professional stage debut in serious music. The date was March 15, 1895 at the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. The work in which he appeared was a now-forgotten opera, L’Amico Francesco, by the amateur composer Domenico Morelli. A string of further engagements in provincial opera houses followed, and he received instruction from the conductor and voice teacher Vincenzo Lombardi that improved his high notes and polished his style. Three other prominent Neapolitan singers taught by Lombardi were the baritones Antonio Scotti and Pasquale Amato, both of whom would go on to partner Caruso at the Met, and the tenor Fernando De Lucia, who would also appear at the Met and later sing at Caruso’s funeral.

Money continued to be in short supply for the young Caruso. One of his first publicity photographs, taken on a visit to Sicily in 1896, depicts him wearing a bedspread draped like a toga since his sole dress shirt was away being laundered. At a notorious early performance in Naples, he was booed by a section of the audience because he failed to pay a claque to cheer for him. This incident hurt Caruso’s pride. He never appeared again on stage in his native city, stating later that he would return “only to eat spaghetti”.

During the final few years of the 19th century, Caruso performed at a succession of theaters throughout Italy until, in 1900, he was rewarded with a contract to sing at La Scala in Milan, the country’s premier opera house. His La Scala debut occurred on December 26 of that year in the part of Rodolfo in Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème with Arturo Toscanini conducting. Audiences in Monte Carlo, Warsaw and Buenos Aires also heard Caruso sing during this pivotal phase of his career and, in 1899–1900, he appeared before the Tsar and the Russian aristocracy at the Mariinsky Theater in St Petersburg and the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow as part of a touring company of first-class Italian singers.

The first major operatic role that Caruso was given the responsibility of creating was Loris in Umberto Giordano’s Fedora, at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, on November 17, 1898. At that same theater, on November 6, 1902, he would create the role of Maurizio in Francesco Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur. (Puccini considered casting the young Caruso in the role of Cavaradossi in Tosca at its premiere in 1900, but ultimately chose the older, more established Emilio De Marchi instead.)

Caruso took part in a “grand concert” at La Scala in February 1901 that Toscanini organised to mark the recent death of Giuseppe Verdi. Among those appearing with him at the concert were two other leading Italian tenors of the day, Francesco Tamagno (the creator of the protagonist’s role in Verdi’s Otello) and Giuseppe Borgatti (the creator of the protagonist’s role in Giordano’s Andrea Chénier). He embarked on his last series of La Scala performances in March 1902, creating along the way the principal tenor part in Germania by Alberto Franchetti.

A month later, on April 11, he was engaged by the Gramophone & Typewriter Company to make his first group of acoustic recordings, in a Milan hotel room, for a fee of 100 pounds sterling. These 10 discs swiftly became best-sellers. Among other things, they helped to spread 29-year-old Caruso’s fame throughout the English-speaking world. The management of London’s Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, signed him for a season of appearances in eight different operas ranging from Verdi’s Aida to Don Giovanni by Mozart. His successful debut at Covent Garden occurred on May 14, 1902, as the Duke of Mantua in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Covent Garden’s highest-paid diva, the Australian soprano Nellie Melba, partnered him as Gilda. They would sing together often during the early 1900s. In her memoirs, Melba praised Caruso’s voice but considered him to be a less sophisticated musician and interpretive artist than Jean de Reszke—the Met’s biggest tenor drawcard prior to Caruso.

The Metropolitan Opera

The following year, 1903, Caruso traveled to New York City to take up a contract with the Metropolitan Opera. (The gap between his London and New York engagements was filled by a series of performances in Italy, Portugal and South America.) Caruso’s Met contract had been negotiated by his agent, the banker and impresario Pasquale Simonelli. Caruso’s debut at the Met was in a new production of Rigoletto on November 23, 1903. This time, Marcella Sembrich sang opposite him as Gilda. A few months later, he began a lasting association with the Victor Talking Machine Company. He made his first American records on February 1, 1904, having signed a lucrative financial deal with Victor. Thereafter, his recording career ran in tandem with his Met career, the one bolstering the other, until his death in 1921.

Caruso purchased the Villa Bellosguardo, a palatial country house near Florence, in 1904. The villa became his retreat away from the pressures of the operatic stage and the grind of travel. Caruso’s preferred address in New York City was a suite at Manhattan’s Knickerbocker Hotel. (The Knickerbocker was erected in 1906 on the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street.) Caruso commissioned the New York jewelers Tiffany & Co. to strike a 24-carat-gold medal adorned with the tenor’s profile. He presented the medal in gratitude to Simonelli as a souvenir of his many well-remunerated performances at the Met (see illustration, above).

In addition to his regular New York engagements, Caruso gave recitals and operatic performances in a large number of cities across the United States and sang in Canada. He also continued to sing widely in Europe, appearing again at Covent Garden in 1904–07 and 1913–14; and undertaking a UK tour in 1909. Audiences in France, Belgium, Monaco, Austria, Hungary and Germany heard him, too, prior to the outbreak of World War I. In 1909, Melba asked him to participate in her forthcoming tour of Australia; but he declined the invitation because of the significant amount of travel time that such a trip would entail.

Members of the Met’s roster of artists, including Caruso, had visited San Francisco in April 1906 for a series of performances. Following an appearance as Don Jose in Carmen at the city’s Grand Opera House, a strong jolt awakened Caruso at 5:13 on the morning of the 18th in his suite at the Palace Hotel. He found himself in the middle of the San Francisco Earthquake, which led to a series of fires that destroyed most of the city. The Met lost all the sets, costumes and musical instruments that it had brought on tour but none of the artists was harmed. Holding an autographed photo of President Theodore Roosevelt, Caruso ran from the hotel, but was composed enough to walk to the St. Francis Hotel for breakfast. Charlie Olson, the broiler cook, made the tenor bacon and eggs. Apparently the quake had no effect on Caruso’s appetite, as he cleaned his plate and tipped Olson $2.50. Caruso made an ultimately successful effort to flee the city, first by boat and then by train. He vowed never to return to San Francisco and kept his word.

In November 1906, Caruso was charged with an indecent act allegedly committed in the monkey house of New York’s Central Park Zoo. The police accused him of pinching the bottom of a married woman. Caruso claimed a monkey did the bottom-pinching. He was found guilty as charged, however, and fined 10 dollars, although suspicions linger that he may have been entrapped by the victim and the arresting officer. The leaders of New York’s opera-going high society were outraged initially by the incident, which received widespread newspaper coverage, but they soon forgot about it and continued to attend Caruso’s Met performances. Caruso’s fan base at the Met was not restricted, however, to the wealthy. Members of America’s middle classes also paid to hear him sing—or buy copies of his recordings—and he enjoyed a substantial following among New York’s 500,000 Italian immigrants.

Caruso created the role of Dick Johnson in the world premiere of Puccini’s La fanciulla del West on December 10, 1910. The composer conceived the music for the tenor hero with Caruso’s voice specifically in mind. With Caruso appeared two more of the Met’s star singers, the Czech soprano Emmy Destinn and baritone Pasquale Amato. Toscanini, then the Met’s principal conductor, presided in the orchestra pit.

Later career and personal life

From 1916 onwards, Caruso began adding heroic parts such as Samson, John of Leyden, and Eléazar to his repertoire. Caruso toured the South American nations of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil in 1917, and two years later performed in Mexico City. In 1920, he was paid the then-enormous sum of 10,000 American dollars a night to sing in Havana, Cuba.

The United States had entered World War I in 1917, sending troops to Europe. Caruso did extensive charity work during the conflict, raising money for war-related patriotic causes by giving concerts and participating enthusiastically in Liberty Bond drives. The tenor had shown himself to be a shrewd businessman since arriving in America. He put a sizable proportion of his earnings from record royalties and singing fees into a range of investments. Biographer Michael Scott writes that by the end of the war in 1918, Caruso’s annual income tax bill amounted to $154,000.

Prior to World War I, Caruso had been romantically tied to an Italian soprano, Ada Giachetti, who was a few years older than he was.Though already married, Giachetti bore Caruso four sons during their liaison, which lasted from 1897 to 1908. Two survived infancy: Rodolfo Caruso (born 1898) and singer/actor Enrico Caruso, Jr. (1904–1987). Ada had left her husband, manufacturer Gino Botti, and an existing son to cohabit with the tenor. Information provided in Scott’s biography of Caruso suggests that she was his vocal coach as well as his lover. Statements by Enrico Caruso, Jr. in his book tend to substantiate this. Her relationship with Caruso broke down after 11 years and they separated. Giachetti’s subsequent attempts to sue him for damages were dismissed by the courts.

Towards the end of the war, Caruso met and wooed a 25-year-old socialite, Dorothy Park Benjamin (1893-1955). She was the daughter of a wealthy New York patent lawyer. In spite of the disapproval of Dorothy’s father, the couple wed on August 20, 1918. They had a daughter, Gloria Caruso (1919–1999). Dorothy lived until 1955 and wrote two books about Caruso, published in 1928 and 1945. The books include many of Caruso’s letters to his wife.

A fastidious dresser, Caruso took two baths a day and liked good Italian food and convivial company. He forged a particularly close bond with his Met and Covent Garden colleague Antonio Scotti — an amiable and stylish baritone from Naples. Caruso was superstitious and habitually carried good-luck charms with him when he sang. He played cards for relaxation and sketched friends, other singers and musicians. Dorothy Caruso said that by the time she knew him, her husband’s favorite hobby was compiling scrapbooks. He also amassed a valuable collection of rare postage stamps, coins, watches and antique snuffboxes. Caruso was a heavy smoker of strong Egyptian cigarettes, too. This deleterious habit, combined with a lack of exercise and the punishing schedule of performances that Caruso willingly undertook season after season at the Met, may have contributed to the persistent ill-health which afflicted the last months of his life.

Illness and death

On September 16, 1920, Caruso concluded three days of Victor recording sessions at Trinity Church in Camden, New Jersey. He recorded several discs including the Domine Deus and Crucifixus from the Petite messe solennelle by Rossini. These recordings were to be his last.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband’s health began a distinct downward spiral in late 1920 after returning from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography, Enrico Caruso, Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on December 3 had hit him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported).A few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was December 4, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and developed a cough and a “dull pain in his side”. It appeared to be a severe episode of bronchitis. Caruso’s physician, Philip Horowitz, who usually treated him for migraine headaches with a kind of primitive TENS unit, diagnosed “intercostal neuralgia” and pronounced him fit to appear on stage, although the pain continued to hinder his voice production and movements.

During a performance of L’elisir d’amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave only three more performances at the Met, the final one being as Eléazar in Halévy’s La Juive, on December 24, 1920. By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso some morphine and codeine and called in another doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso’s health deteriorated further during the new year. He experienced episodes of intense pain because of the infection and underwent seven surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest and lungs.He returned to Naples to recuperate from the most serious of the operations, during which part of a rib had been removed. According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be examined by an unhygienic local doctor and his condition worsened dramatically after that. The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome, recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 a.m. local time, on August 2, 1921. He was 48. The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst subphrenic abscess.The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of the Church of San Francesco di Paola for Caruso’s funeral, which was attended by thousands of people. His embalmed body was preserved in a glass sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

Historical and musical significance

Caruso’s 25-year career, stretching from 1895 to 1920, included 863 appearances at the New York Metropolitan Opera before he died at the age of 48. Thanks in part to his tremendously popular phonograph records, Caruso was one of the most famous personalities of his day and his fame has endured to the present. He was one of the first examples of a global media celebrity. Beyond records, Caruso’s name became familiar to millions through newspapers, books, magazines, and the new media technology of the 20th century: cinema, the telephone and telegraph. Caruso toured widely both with the Metropolitan Opera touring company and on his own, giving hundreds of performances throughout Europe, and North and South America. He was a client of the noted promoter Edward Bernays, during the latter’s tenure as a press agent in the United States. Beverly Sills noted in an interview: “I was able to do it with television and radio and media and all kinds of assists. The popularity that Caruso enjoyed without any of this technological assistance is astonishing.”

Caruso biographers Pierre Key, Bruno Zirato and Stanley Jackson attribute Caruso’s fame not only to his voice and musicianship but also to a keen business sense and an enthusiastic embrace of commercial sound recording, then in its infancy. Many opera singers of Caruso’s time rejected the phonograph (or gramophone) owing to the low fidelity of early discs. Others, including Adelina Patti, Francesco Tamagno and Nellie Melba, exploited the new technology once they became aware of the financial returns that Caruso was reaping from his initial recording sessions.

Caruso made more than 260 extant recordings in America for the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) from 1904 to 1920, and he earned millions of dollars in royalties from the retail sales of the resulting 78-rpm discs. (Previously, in Italy in 1902–1903, he had cut five batches of records for the Gramophone & Typewriter Company, the Zonophone label and Pathé Records.) He was also heard live from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1910, when he participated in the first public radio broadcast to be transmitted in the United States.

Caruso also appeared in two motion pictures. In 1918, he played a dual role in the American silent film My Cousin for Paramount Pictures. This film included a sequence depicting him on stage performing the aria Vesti la giubba from Leoncavallo’s opera Pagliacci. The following year Caruso played a character called Cosimo in another film, The Splendid Romance. Producer Jesse Lasky paid Caruso $100,000 each to appear in these two efforts but My Cousin flopped at the box office and The Splendid Romance was apparently never released. Brief candid glimpses of Caruso offstage have been preserved in contemporary newsreel footage.

While Caruso sang at such venues as La Scala in Milan, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in London, the Mariinsky Theater in St Petersburg, and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, he was also the leading tenor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City for 18 consecutive seasons. It was at the Met, in 1910, that he created the role of Dick Johnson in Giacomo Puccini’s La fanciulla del West.

Caruso’s voice extended up to high C in its prime and grew in power and weight as he grew older. He sang a broad spectrum of roles, ranging from lyric, to spinto, to dramatic parts, in the Italian and French repertoires. In the German repertoire, Caruso sang only two roles, Assad (in Karl Goldmark’s The Queen of Sheba) and Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, both of which he performed in Italian in Buenos Aires in 1899 and 1901, respectively.