At the end of the Scherzo movement in the symphony original version, Mahler suggests a suitable pause before the next movement. The radical change in mood seemed to him to necessitate a moment of silence. For what follows is one of the strangest most uncanny movements ever included in the symphony before them. In this movement, Mahler presents a grotesquely ironic funeral march, whose main theme is based on all things upon the popular children’s round forever Jacques, known in German as Buddha Martin. To more aptly fit the occasion Mahler sets the tune in the minor key, thus completely changing its character from that of a light hearted carefree nursery rhyme to a goal for the funeral march, Mahler admitted that even as a child, Buddha Martin struck him not as being gay as it usually was sung, but rather deeply tragic. That gives us some idea of Mahler’s strange character.

As indicated in Mahler’s original program for the symphony, this curious movement was inspired by a well known woodcut, by the 19th-century German artists more it’s fun Shinde, entitled The Huntsman’s funeral. It depicts a hunter’s funeral procession in which the pallbearers and other celebrants are not his companions or fellow Huntsman, but the very animals he stalked on a stint as a romantic artist like Mahler was fascinated with if not deeply troubled by death in the abstract, as was john paul Rector, and eta Hoffman romantic writers of a much earlier period. In advance, Vince would call the pole bearing animals are far from Solon or gloomy, they even appear to celebrate the death of their predator as a conquest.

In his original program, Mahler also referred to etching by the French artist, Jacques callow. Live from 5092 to 1635. Presumably, Mahler intended to indicate that this movement has much in common with Carlos’s artistic penchant for grotesque irony, as it relates to the themes of fate and death. Much like the early romanticism of Hoffman icon Dorf, and john paul Rector, the concept of death was presented with a devilish sometimes ironic twist.

The theme of poetic justice implicit in the bunch tint woodcut so captivated Mahler that it probably served as an essential element in the conception of the movement. molars own sense of the McCobb or grotesque, whether in the service of the ironical or radical or diabolical, already had manifest itself in several of the wounded horn songs, particularly those dealing with military subjects, or legendary tales, in which personification of animals plays a leading role. After the canonic Freyr Jacques of funeral march theme seems to have played itself out. Moller conjures up I nostalgic reverie, in which recollections of joyful moments in the life of the hero flash before the mind, as if in a daydream.

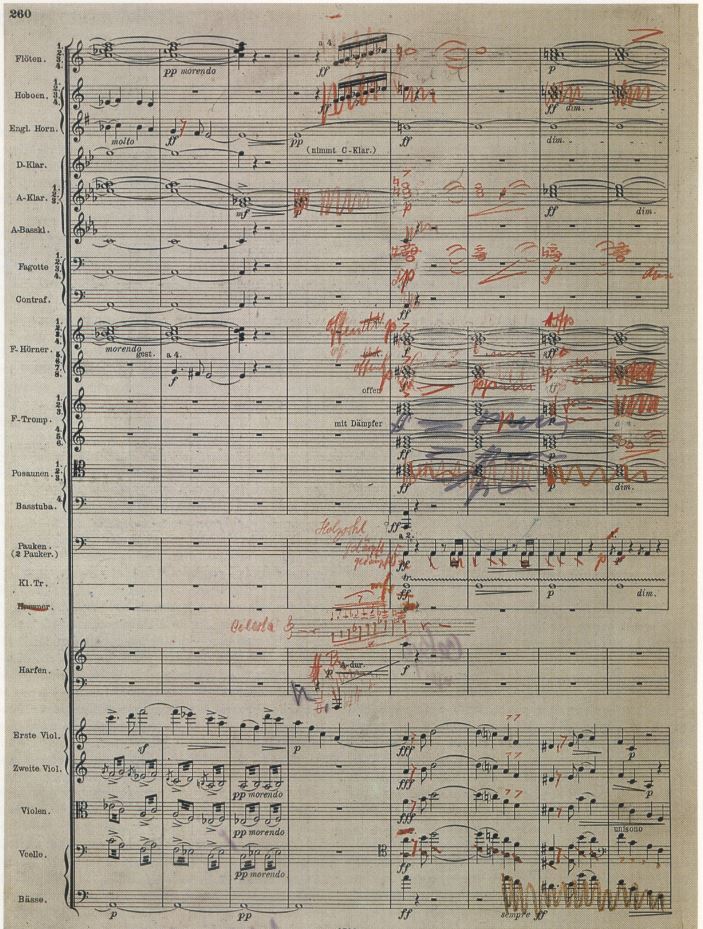

The middle section uses the last of the wayfarer songs for its principal thematic material. an abbreviated version of the funeral march closes one of Mahler’s most fascinating symphonic movements. At the outset, the funeral march tread is immediately established in very soft timpani strokes that Mahler directs to be played in a solemn and measured fashion without dragging the temple. Repeating March tread uses falling fourths the symphonies basic model after just two measures of muted solo double bass in its highest register ekes out the friar aka tune in D minor. Models’ choice of such an EN melodic instrument is a double bass was purposeful. In fact, he substituted the double bass for the cello in one of his numerous revisions of the score, before the first published edition.

Mahler obviously intended to set the tone of the movement immediately as one of grotesque irony by both his choice of this gruff instrument to introduce the prayer Shaka tune, but also by having it played in the instruments high registered person sounds strained and craggy. It would therefore be inappropriate and even counterintuitive. To have the double basis use too much vibrato to sweeten the tone quality.

Mahler’ss perverse treatment of the nursery rhyme tune could imply the childlike innocence thus far pervasive in the symphony has turned sour. Just as the innocence of the animals portrayed in the bunch bent woodcut has been subverted into vengeful animus against their predator Mahler makes inventive use of kinetic imitation akin to a round in which the tune is usually Sung. He directs that each entrance of the tune in a different instrumental group, the played slowly and without any crescendo so that the build up in layers of sound increases the dynamic level naturally. As the round continues to solo oboe enters with a counter melody, which is completely out of keeping with the solemnity of the occasion, instead of a plaintive theme, which would be expected in a funeral march.

The oboe plays a rather cocky was Korean dance tune, stated softly but with defiance.

Notice the contrast between the clip dotted rhythm of the elbows counter theme, characteristic of bohemian dance music, and the simple four-square rhythms of the friarage aka to hear we can sense the effect of bunch Finn’s edging on the music most tellingly, one can just imagine the victorious animals pompously struggling before the dead hunter’s coffin and feign solemnity, that turns to arrogant derisive ease. The use of what amounts to a village band to play the doleful main theme is one of many instances in which Mahler creates an ironic effect that might appear banal, by reason of the thematic content becomes even more outrageous as the funeral march eases into a slow Yiddish dance tune in D minor, played by to oboes in minor thirds, combined with a counter theme for trumpet duet, also in thirds, accompanied by a double-time variant of the opening March Trent. Mahler certainly would have heard the music of this sort in his youth, possibly at a Jewish wedding celebration.

Despite Mahler’s alleged aversion to Jewish ritual, Yiddish music must have had some effect, since it provides him with melodic material by which to evoke and the style Jake reverie of happier times long garden by suddenly this dance tunes abruptly interrupted by a more spirited one. Also in D minor, on E, flat clarinets and bassoons, a fascinating combination of pitches and tambours. It begins off the bead on a rising fourth, and is accompanied by an own power rhythm, played quietly by a Turkish symbol and bass drum, trading up beats and down beats with tapping rhythmic accompaniment in the strings, clipped dotted rhythms and grace note and figures indicate the influence of Gypsy music.

Mahler directs that this brief segment be played with parody and other indications of his whimsical intentions. These two dance themes are intended to evoke a feeling of nostalgic reverie, romanticized memories of the carefree days of youth and the joys of early manhood after only a few measures, the Muse eases its way back to the Yiddish oboe theme, now played by the violins, and supported by the trumpet counter theme, imitated inversion by woodwinds. In a lighter orchestral treatment, the succeeding oompah dance tune also returns briefly, just as softly as before, but with more zest generated by a delightful upward swoop of a seventh in fluid and violins.

One of Mahler’s most masterful transitions now follows as the tonality shifts back to the minor. The second Yiddish dance tune returns now sounding more wistful than before. Almost unnoticeably the original March tread enters on the timpani and lower strings, memories of past happiness now fade, and the reprise of the funeral march with its tragic irony brings us back to stark reality.

As the funeral march slowly fades away on a short cadential figure, the tread peters out and the rhythm becomes more syncopated until it gradually settles on a steady rhythmic pattern. Out of these reconfigured rhythms, the movement’s middle section emerges.

We seem to be floating on an ability cloud of carries us into a serene dream world. Here we linger consoled by the soothing sounds of a romantic idol to last love, a song theme softly enters muted strings.

Here again, Mahler quotes himself, the string’s dreamy theme is the very same melody that Mahler introduced in the middle section of the song deeds five blowing Hogan, the last of the gazelle and songs.

While referring to its appearance here as a tender recollection of loss, youth, and love. The words of the song convey the same meaning, the entire middle section is virtually a direct quotation of the second half of the song, beginning with the words out of this thalassa state I’m to the very end, including the rhythmical transition passage. The melody of the song theme begins on a rising fourth, that is repeated an octave higher in the midst of the theme, thus referring to the symphonies motto, as well as each of the folk themes presented in the D section. The use of two horns for the vocal line, originally sung to the songs final words lieben lied on Veldt on top crown evokes a feeling of tender farewell.

This is the same passage as in the original song, a short pause follows to allow the listener a moment to awaken from this nostalgic dream, before returning to the doleful music of the funeral march. It returns in a capsulized version of the opening section, somewhat more agitated than before.

Mahler directs that the Austrian dance tune heard toward the opening of the movement in the oboe be played arrogantly, first by the E flat clarinet, and then on the flute. Before the flute is finished trumpets in thirds enter on a new Yiddish-sounding tune that replaces the oboe dance theme heard earlier. Although related to it, the home pod dance tune immediately follows without any tempo change, I mean lighter orchestration and before Suddenly, the music plunges headlong into a much faster version of the one pod dance to an example of Mahler’s midstream tempo shifts that often unexpectedly break both the pace and the mood. Hardly has this oompah theme time to assert itself before the tempo eases up on a lovely cook cadential phrase and violins that appeared earlier at the end of the funeral march. Then the yudishe oboe theme finally returns here played softly by oboes clarinets and English horn. Here, it sounds somewhat more melancholy than it did before the bridge passage to the middle section violins and muted cellos follow with an inverted version of the theme set against the original tune in contrary motion. It’s gentle, strange-sounding like a tender lullaby.

When the march tread softly starts up again in the timpani, we realize that it actually was never absent, for it was hidden in pizzicato No Strings throughout the previous section, Mahler provides a delightful touch here by referring to the last three notes of the nursery rhyme tune on the harp.

The brash Harrigan theme played earlier by the oboe Asserts Itself, now played soberly by a solo bassoon, with none of its former arrogance. It finishes with a flick on the cello and a hushed, pizzicato treatment of its last few notes on the violas in typical malaria and fashion fragmented references to earlier music in the movement, the music slowly fades on the original March tread, over the final appearance of the falling fourths in bass clarinet to hardly audible strokes on the bass drum, doubled by pizzicato plugs on the double bass in the movement quietly.

We are left in complete silence to await the onset of the magnificent finale in which Mahler will respond to the intrusion of death in the midst of life, represented by this ironic parody of a funeral march.

By Lew Smoley