Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps (1864-1945).

- Profession: Writer, critic, journalist, salonniere (Palais Lieben-Auspitz, Vienna). Austrian publicist, with a well-visited salon, a central figure in Viennese cultural life around 1900.

- Residences: Vienna, Salzburg, Paris, Algiers.

- Relation to Mahler: Closest friend Alma Mahler (1879-1964).

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 13-04-1864 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 16-10-1945 Paris, France.

- Buried: 00-00-0000 Pere Lachaise cemetery, Paris, France. Her husband is buried in Dobling cemetery, Vienna, Austria.

See also: House Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps.

Bertha or Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps, born as Bert(h)a Szeps was an Austrian writer, journalist, and critic. Berta Szeps was the daughter of Galician Jewish liberal newspaper publisher Moritz Szeps and was raised in Vienna. She was married to the Hungarian anatomist Emil Zuckerkandl. From end of the 19th century until 1938, she led an important literary salon in Vienna, originally from a villa in Döbling, later in the Oppolzergasse area. Many famous Viennese artists and personalities including Gustav Klimt, Gustav Mahler, Max Reinhardt, Arthur Schnitzler and others frequented the salon. Protégés of the salon include Anton Kolig and Sebastian Isepp of the Nötsch Circle. Her sister Sofie Szeps (aka Sophie) was married to Paul Clemenceau, the brother of the French President Georges Clemenceau, and, therefore, she also had good ties to Parisian artistic circles. She also translated a number of plays from French to German and was a cofounder of the Salzburg Music Festival. In 1938, she emigrated to Paris and later to Algiers.

Berta Szeps-Zuckerkandl was one of the most remarkable personalities of Viennese society during the last decades of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and up until the darkest hours of history during the Second World War. Due to the unique position of her father, Moriz Szeps, boss of the newspaper »Neues Wiener Tagblatt« and closest advisor to the unfortunate Crown Prince Rudolf, who committed suicide in Mayerling, it was not hard for her to establish contacts within European high society.

Her marriage to Emil Zuckerkandl, a famous anatomist of the Viennese School, opened the door for her into the world of science. Berta Zuckerkandl was active for almost half a century as a novelist, journalist and writer, but what she truly loved was modern art. Her salon was a meeting place for countless artists, literati and academics, and her circle of friends included Auguste Rodin, Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Gustav Mahler and Max Reinhardt.

On one of the rare occasions when Mahler attended such a social event at Zuckerkandl´s salon, in November 1901, he met Alma Schindler, who was known throughout Vienna for her beauty. He fell in love with her immediately and married her just a few months later. For many years, Berta was Alma´s closest friend, someone to whom Alma did not merely owe the meeting with her first husband.

Berta Zuckerkandl was one of Austria’s foremost cultural impresarios and ambassadors-at-large, who energetically championed the creation of an Austrian avant-garde in art, design, and literature. Eyewitnesses cite her salon as the birthplace of the Vienna Secession (1897); the salon also nurtured the Wiener Werkstätte (“Viennese Workshops” for design, founded in 1903) and the Salzburg Music Festival after the First World War. The ideas discussed in her salon were propagated in her columns for Viennese newspapers and articles in German art journals, such as Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration.

More

Berta Zuckerkandl was a journalist and art critic of the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung and later of the Neue Wiener Journal. Hostess of a famous Viennese salon, she fought for the recognition of modern Austrian art, for a cultural and political dialogue between Austria and France, and for pressing humanist causes for almost fifty years, between 1890 and 1938.

Born on April 13, 1864, to Amalie (Schlesinger) (1838-1912) and the newspaper tycoon Moritz Szeps (1834-1902), the founder and publisher of the Wiener Tagblatt, Berta Zuckerkandl was the second daughter of five children. Among the experts whom her father hired to tutor his daughters at home, was the renowned art historian Albert Ilg (1847-1896), who favored Baroque art. Zuckerkandl grew up witnessing her father’s stormy career and political engagements. Moritz Szeps was a close advisor of the liberal Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf (1858-1889), and a supporter of an alliance between Austria and France through his connections with liberal French politicians such as Léon Gambetta (1838-1882) and Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929). Clemenceau’s brother, Paul, married Szeps’ eldest daughter Sophie. Berta continued her father’s political mission, opposing Austria’s annexation movement to Germany after WWI, and promoting cultural exchange with France. During her visits to Paris Berta became acquainted with famous artists such as Eugène Carrière (1849-1906) and Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Learning about the Dreyfus affair at her sister’s salon, Zuckerkandl supported the fight to recognize his innocence.

In 1886, Berta married Emil Zuckerkandl (1849-1910), a professor of anatomy. Their only son was born in 1895. Among the guests in the early days of her renowned salon were her husband’s colleague, the neuropsychiatrist Richard Krafft-Ebing (1840-1902), the author and critic Hermann Bahr (1863-1934) and the composers Johann Strauß the younger (1825-1899) and Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Fighting side by side with her colleagues, Bahr and Ludwig Hevesi (1843-1910), Zuckerkandl raised the flag for modern Austrian art, defending and promoting such artists as Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), and architects Otto Wagner (1841-1918) and Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956), as well the reputation of the Vienna Sezession and the Viennese Workshops (“Wiener Werkstätte”). Furthermore, she introduced to the Austrian public new personalities such as the German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) and the French fashion designer Paul Poiret (1879-1944). Her salon became an important artistic center. In 1905, Zuckerkandl provoked a sensation by publishing an interview with Klimt, who, in the name of the freedom of art, declared that he would buy back the panels he had designed for the Viennese university ceiling, which had been rejected by the Austrian Ministry of Education. In 1908, Zuckerkandl published a selected collection of her essays on contemporary art.

During WWI, despite growing national chauvinism, Zuckerkandl had the courage to reveal herself as a pacifist by publishing an open letter by young French authors calling for peace. At the same time she published an appeal for a humanitarian commission for the suffering Jews in Galicia and demanded tolerance from the Viennese toward the flood of immigrants, mainly Jews, from the eastern provinces. In 1917, Zuckerkandl utilized the close connections to French politicians which she had established at her sister’s salon and, together with her brother Julius Szeps (1867-1924), the editor of the liberal newspaper Fremden-Blatt, strove for a separate peace between Austria and the allies. After the war, recognized by both the Socialist and the Conservative parties as an unofficial Austrian diplomat, Zuckerkandl arranged informal contacts with French politicians. Utilizing her French connection, Zuckerkandl’s two major achievements were to enable the Hoover commission to aid ailing Austria after the war and, more than ten years later, to persuade the Austrian Chancellor to review the case of Philipp Halsmann, a Jew from Riga visiting Tyrol with his father, who was jailed after being falsely accused by a local antisemitic restaurant owner for killing his father. As a result of her intervention, Halsmann was pardoned.

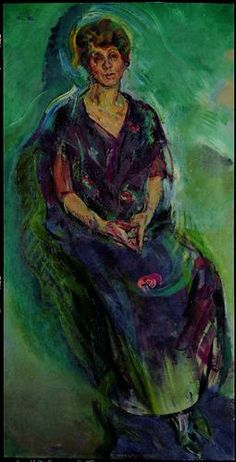

House Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps by Anton Kolig (1915).

During the 1920s, Zuckerkandl promoted the theater projects of Max Reinhardt (1873-1943) and Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929), especially the Salzburg Festivals. She moved to the inner city and began the second round of her salon, hosting such famous authors as Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), Franz Werfel (1890-1945), Felix Salten (1869-1945), Richard Beer-Hofmann (1866-1945) and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, as well as leading Socialists and Conservatives such as Julius Tandler (1869-1936) and Ignaz Seipel (1876-1932). At the end of 1922 she left the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung and began publishing in the Neue Wiener Journal and, sporadically, also in the Wiener Tag, Volkszeitung and Bühne and other journals. In 1924, Zuckerkandl published a series of interviews with politicians, including the British and the French prime ministers and finance ministers. Committed to an Austrian-French dialogue, Zuckerkandl translated into German the plays of the French dramatists Paul Géraldy (1885-1983), Henri Lenormand (1882-1951), Jean Anouilh (1910-1987), Marcel Achard (1899-1974) and Jacques Bousquet (1883-?) – work for which she was awarded the Order of the Legion of Honor.

In 1934, after the establishment of the Austro-Fascist government in Austria, Zuckerkandl gave up her political activities. Following the annexation of Austria in March 1938, she escaped to Paris, where her son Fritz had been living since 1935. In Paris she established her third salon, where her guests included the conductor Bruno Walter (1876-1962) and Alma and Franz Werfel. Together with other emigrés she worked for the liberation of Austria. Zuckerkandl’s memoirs were published in English, French and German. A film script on the ‘Tiger’, Georges Clémenceau, was published as a book in 1944. In spring 1940, she fled to Algeria, where her son was already waiting for her. After the liberation of Algeria at the end of 1942, she worked in the Austrian section of a radio station established by the Allies. In September 1945, she returned, sick, to Paris, where she died on October 16, 1945.

Works

- Die Pflege der Kunst in Österreich 1848-1898.

- Dekorative Kunst und Kunstgewerbe. Wien, 1900

- Zeitkunst Wien 1901-1907. Heller, Wien, 1908

- Ich erlebte 50 Jahre Weltgeschichte. Bermann-Fischer Verlag, Stockholm, 1939

- Clemenceau tel que je l’ai connu. Algier, 1944

- Österreich intim. Erinnerungen 1892-1942. Propyläen, Frankfurt/Main, 1970 (paperback edition: Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main, 1988; ISBN 3-548-20985-8)