This article has been provided thanks to the generosity of Michael Haas from Forbidden Music.

You can check get his book here.

- Profession: Musicologist, composer. Univ. prof. dr. phil.

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 21-10-1885 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 09-11-1974 Oxford, England. Aged 89.

- Buried: 29-11-1974 Central cemetery, Vienna, Austria. Grave 32C-38.

Egon Joseph Wellesz was an Austrian-born British composer, teacher and musicologist, notable particularly in the field of Byzantine music. Although both parents of Wellesz’s were Hungarian Christians, they both had Jewish ancestry. He received a Protestant upbringing, but later converted to Catholicism. Wellesz studied in Vienna under Arnold Schoenberg – purportedly his first private pupil – as well as Guido Adler, who founded the musicological institute in Vienna and was a leading editor of the Austrian Denkmaler. These dual influences shaped much of his musical and scholarly thought. In 1913, Wellesz embarked upon what would become a lifelong interest in the musical achievements of Byzantium.

Wellesz left Austria for England in the wake of the Anschluss – more specifically, Wellesz was in Amsterdam at the time by good fortune, to hear his orchestral piece Prosperos Beschwörungen conducted by Bruno Walter on that day. In England he was interned as an enemy alien, ultimately in Hutchinson Camp in the Isle of Man, but he gained his release in 1943 thanks to the intercession of H. C. Colles, the long standing chief music critic of The Times.

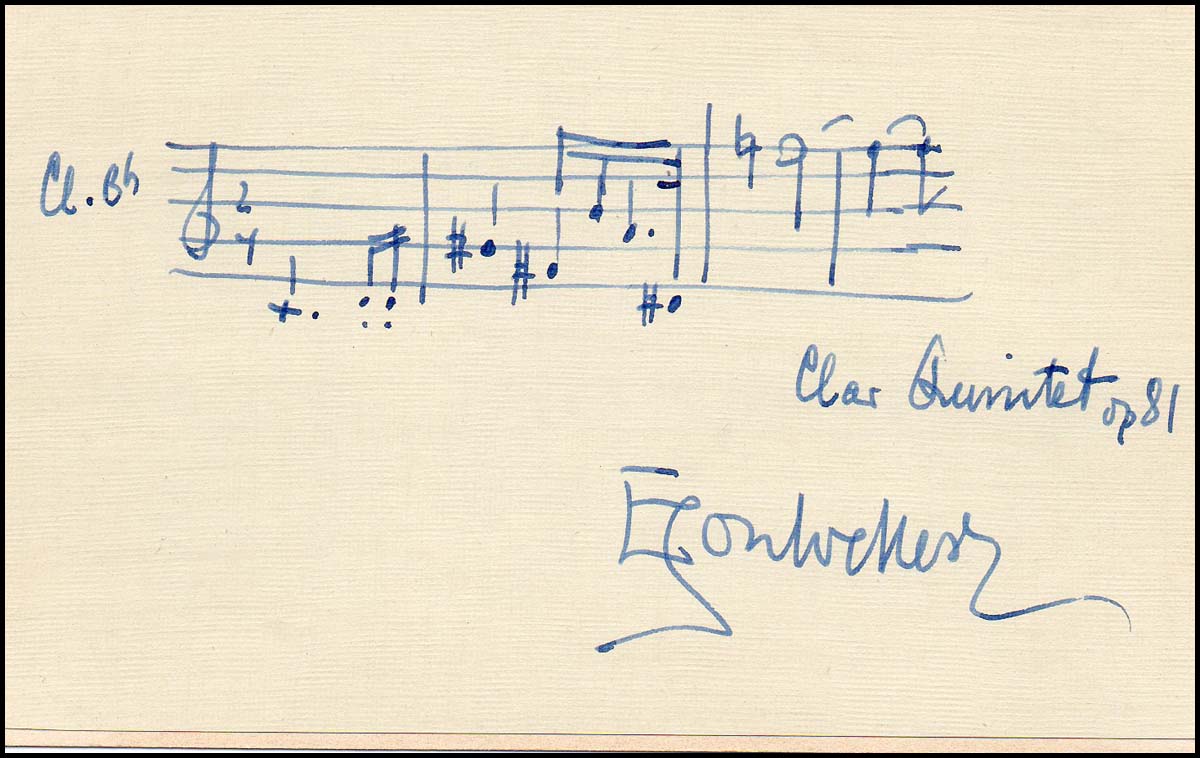

Altogether he wrote nine symphonies and an equal number of string quartets, the former starting, in 1945 only with his arrival in England and the latter series of works spread throughout his life. Other compositions by him include operas, one of which (Die Bakchantinnen) was revived and recorded a few years ago; an octet with the same orchestration as Schubert’s; piano and violin concertos (one of each); and a suite for violin and orchestra.

Stylistically his earliest music, somewhat like that of Ernst Krenek, is in a harsh but recognisably tonal style; there is a definite second period of sorts around the time of the first two symphonies (1940s) in which his music has a somewhat Brucknerian sound – in the symphonies sometimes an equal breadth, though still with something of a 20th-century feel and harmonies – but after his fourth symphony (the Austriaca) his music is more tonally vague in character, with serial techniques used. This idiom is consistent with hints of tonality, such as can be found in his eighth string quartet. Despite his composing, Wellesz remains best known for his extensive scholarly contributions to the study of Byzantine music. These contributions brought for him an honorary doctorate from Oxford (where he later taught) in 1932. A portrait was made of Wellesz by Jean Cooke, who had been commissioned for the work by Lincoln College, University of Oxford.

Compositions

Wellesz’s works as a composer amount to at least 112 works with opus numbers as well as some 20 works without opus number. He busied himself in a variety of media. Recently, interest in Wellesz’s music has increased. A complete recording of his nine symphonies is available, although his music has generally been sparsely represented on CD or LP. His 3rd symphony (1950-19511), published posthumously, received its world premiere in Vienna in 2000. Several of his symphonies have titles, including the second (The English), and the seventh (Contra torrentum).

More

Wellesz was born into a comfortable middle-class Jewish family originally from the Hungarian half of the Dual Monarchy. He related in later life to friends in Oxford that he sat on the lap of Johannes Brahms. Presuming this to be true, it would indicate that his family was one of the well-off families that made up the Liberal circles that Brahms frequented such as Miller zu Aichholz family and Ludwig Botzmann. He studied piano as a child with Carl Frühling, another Brahms disciple who had also been the piano teacher of Wellesz’s mother. Hearing Gustave Mahler conduct Der Freischütz at the age of 14 convinced him that he would become a composer. Notwithstanding this desire, after completion of the Franz Joseph Gymnasium he entered Vienna’s university to study Jurisprudence. It was not long, however, before he switched to musicology and began to study with Mahler’s friend from childhood, Guido Adler.

Despite his passionate interest in Baroque opera – a passion that Adler helped promote and would accompany Wellesz throughout his life and influence his own work, it was a fellow musicology student, Karl Horwitz (1884-1925) who in 1905 would bring Wellesz to Arnold Schoenberg, who at the time was teaching at the progressive school run by Eugenie Schwarzwald.

Wellesz found himself in the same group of young composers as Alban Berg and Anton Webern and remained close to both until his enforced exile in 1938. He was thus the forgotten fourth composer present during the evolution of Vienna’s Second School. During these opening years of the 20th century, his interests were equally divided between early music and the avant-garde. It was in one of the now famous Schwarzwald salons that he met his wife, the art historian Dr. Emmy Stross, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish banking family.

Egon married Emmy Stross in 1908. Under her married name, Emmy Wellesz, she would become an eminent art historian. Her early interest in Syrian art would likewise stir Wellesz’s interest in the origins of Western music, and eventually lead him to his studies into the Byzantine musical notation of the early church.

Though born Jewish, Wellesz would eventually become a devout Roman Catholic, composing much church music and receiving honours from the Vatican. Nevertheless, it was not until 1917, nine years following their marriage that both Emmy and Egon officially withdrew from Vienna’s Jewish community. It could also be speculated that he felt a public departure from the Jewish Community might shield him from anti-Semitism at the university. Neither Egon nor Emmy would ever refer to their Jewish origins – even in the darkest days following Austria’s annexation, they maintained their status as monarchists, and thus as ‘political refugees’. In any case, Great Britain, as with most countries in 1938, accorded political opponents to Nazism a higher status than Jews, who were deemed to be fleeing Germany out of less signficant ‘racial’ grounds.

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler was without doubt Vienna’s most important and dynamic musical personality in these early years. He was music director of the Imperial Opera and despite huge conflicts, left an imprint, which at the time was even more significant than his work as composer. As Wellesz grew more established in Vienna’s musical circles, he became acquainted with Mahler, who took an interest and helped the younger composer. After Mahler’s death in 1911, Wellesz continued his friendship with Alma and was instrumental in her acceptance of the completion of Mahler’s 10th Symphony by Deryck Cooke and Berthold Goldschmidt. Certainly Wellesz had a clear memory of Mahler’s orchestral balance and tempi when conducting his own works. Over the years, he would become recognised as one of Vienna’s most important Mahler authorities. Herbert von Karajan invited him to give the Gustav Mahler Memorial speech at Vienna’s State Opera in 1960 – the only special event in Vienna planned to honour his centenary year.

In detail

When Wellesz entered Vienna’s University, it was to study law. In 1905, however, he managed to change his subject to musicology, which he studied with the eminent Guido Adler. In 1908 Wellesz completed his Dr. Phil. With Summa cum laude. His dissertation was on the Baroque Austrian composer and contemporary of Christoph Willibald Guck, Giuseppe Bonno, the Italian, but Austrian born predecessor to Salieri. With this and subsequent works on Johann Heinrich and Anton Andreas Schmelzer, as well as Cavalli and the Venetian School, Wellesz positioned himself as a specialist in Baroque opera.

Guido Adler published Wellesz’s edition of J.J. Fux’s opera Costanza e fortezza in his noted series Monuments of Music in Austria. Fux’s Costanza e fortezza was originally commissioned for the coronation of the Emperor Charles the VI and was first performed on August 28, 1723. In 1961, Wellesz received the Fux Medal Pro Musica Austriaca in recognition of his pioneering research in Austria’s early Baroque opera. Four years later in 1965, Wellesz published his Fux monograph with Oxford University Press.

In 1913, Wellesz was appointed to a lectureship in music history at the university, which was converted to professorship without tenure in 1929. His lectures spanned from Vienna’s earliest Baroque in the 17th century to musical developments in the 20th century.

Wellesz first came to Britain in 1906 where he attended lectures in English literature at Cambridge University. In the photo above, taken at the congress of the Musicological Society in 1910, he presented a paper on ‘figured bass’. This encounter brought him into contact with a number of important figures in British musical life who wold be associated with Wellesz during the founding of the International Society of Contemporary Music in 1923. They would also be important in awarding him an honorary doctorate from Oxford University in 1932, and provided him with the necessary resources to emigrate following Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in 1938. In addition, they were able to find him work on Groves Dictionary of Music while based in Oxford until his appointment as fellow of Oxford’s Lincoln College.

Dr. Eugenie Schwarzwald (1872-1940) was a pioneering teacher who founded a school which embodied a number of progressive pedagogic principles in Vienna. It was through her that Wellesz would meet his future wife Emmy and his most important teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, whom Schwarzwald had invited to teach harmony, counterpoint and composition. Wellesz was later joined by Anton Webern, whereas Alban Berg had been studying with Schoenberg prior to Wellesz.

Schwarzwald’s school (featured elsewhere on the Forbidden Music blog) was meant for Vienna’s bright young women, not ‘ladies’ and produced some of the city’s sharpest minds and talents such as the actor Helene Weigel (wife of Berthold Brecht); the writers Hilde Spiel and Vicky Baum along with Anne Freud and of course Emmy Stross, Egon’s future wife.

Schwarzwald did not just run a school, but also a lively salon inviting people such as Oskar Kokoschka, Adolf Loos, Jakob Wassermann, Peter Altenberg and Egon Friedell. It was at such a salon that Egon met Emmy, and later Bartók’s associateBéla Balász (who supplied Bartók with the treatment to The Wooden Prince). Bartók was so taken with Wellesz’s compositions that he pursuaded his own publisher in Budapest, Rószavögyi to take on Wellesz’s works as well.

Wellesz was one of the first to present the music of Debussy, and the French Impressionists in Vienna. His own Vorfrühling – or Early Spring displays more than a passing influence, while keeping the sunlight a darker, central European shade. This adds a sense of foreboding to Viennese Impressionism as heard not only in Vorfrühling but also in Schoenberg’s Guerrelieder, or Webern’s Im Sommerwind. Such influences could also be heard in works by Alexander Zemlinsky and Franz Schreker (1878-1934).

Karl Horwitz, a fellow student of Guido Adler brought Wellesz to Schoenberg around 1905. After a year of harmony and counterpoint, Bruno Walter advised Wellesz to ‘go his own way’. More than a decade later, Wellesz would introduce Josef Matthais Hauer, the originator of the so-called 12-tone system to Schoenberg. Many years later in Oxford, Wellesz explained the relationship of the two composers as ‘Hauer was to Schoenberg as Satie to Debussy’.

Wellesz admired Schoenberg profoundlyand wrote the first monograph of the composer, published in 1920. Alban Berg, in a letter to Wellesz underlines ‘we four’ when referring to himself, Webern, Schoenberg and Wellesz as the original core of the class. Indeed Wellesz would achieve success before his fellow students and use his influence to help Berg and Webern obtain performances in Germany.

Despite the obvious incorporation of French Impressionism into Vorfrühling, the op. 6 piano works are a clear indicator of Schoenberg’s influence. Wellesz showed only the greatest respect for Schoenberg, whose own feelings for Wellesz were more ambivalent. Letters between the two indicate a true closeness, but later while in American exile Schoenberg turned against Wellesz and wrote a lengthy denunciation of him, disowning him as a student.

The years after the First World War and before the rise of National Socialism were the most dynamic of Wellesz’s career. Parallel to his work as Byzantinist, his own compositions began to dominate the most important stages in Central Europe. With the single exception of his Singspiel Scherz, List und Rache, (Jest, Cunning and Revenge), his stage works distinctively recalled the pageantry of the high Baroque with radical usage of movement and dance in opera. His ballets too, were championed by such revolutionaries as Rudolf Laban, Kurt Joos, Ellen Tels and Max Terpis. By the time his works were banned in 1933, his highly ceremonial and colourful musical language had become a distinctive feature. Wellesz had indeed ‘gone his own way’ and it would seem that his fascination with Baroque theatre was in fact, a greater influence than Schoenberg in these inter-war years.

Jakob Wassermann, best known for his book My Life as German and Jew, was a frequent guest of Eugenie Schwarzwald in Altaussee, where he too kept a large summer house. It was there that he and Wellesz met and Wassermann agreed to supply a libretto for an opera entitled Princess Girnara, a story of spiritual beauty defeating the curse of physical ugliness and thus standing in contrast while anticipating Zemlinsky’s Der Zwerg and growing out of the same Zeitgeist as Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten. In both the operas by Zemlinsky and Schreker, spiritual beauty is crushed by physical ugliness. Universal Edition (UE) music publishers, publishers of both Zemlinsky and Schreker must have thought highly of this first opera as they managed to plan a double premiere in both Hanover and Frankfurt in 1921.

At the same time, Wellesz was quickly establishing himself in chamber music circles as well. The Kolisch Quartet, famous for their performances of Schoenberg’s Quartets took up Wellesz’s fourth quartet, which they performed in London in 1920. During the performance, they projected the score on a screen behind the players that ran parallel to the performance.

It was also around this time that Wellesz wrote his book on ‘Orchestration’, which at the time was thought to be the most important work to appear on the subject since Berlioz. Wellesz’s first stage work – even earlier than Princess Girnara was a ballet called Das Wunder der Diana or The Miracle of Diana. It was performed in Mannheim in 1924 and the treatment was by Béla Balász. Wellesz’s suite op. 16 from 1913 is a virtual study in anticipation of the ballet and offers an idea of the musical language of Miracle of Diana.

In 1920, the same year as publication of his Schoenberg biography, Wellesz composed Persisches Ballett or Persion Ballet, based on a treatment by Ellen Tels. It was performed at the Donaueschingen Festival in a version for small orchestra in 1924. The work is dedicated to Schoenberg.

It was also at Altaussee while visiting the Schwarzwalds that Wellesz became acquainted with Hugo von Hofmannsthal who owned Prielau Castle at near-by Zell am See. Hofmannsthal only worked with one other composer: Richard Strauss. Yet he provided Wellesz with the treatment for the ballet Achilles auf Skyros, premiered in Stuttgart in 1926 and the opera Alkestis premiered to great acclaim in Mannheim in 1924. He also offered the Wellesz the treatment to Die Opferung des Gefangenen or The Sacrifice of the Prisoner.

Together the three works form what would become ‘The Heroic Triolgy’ based on ancient cultures and rites, offering opportunities of pageantry with combinations of movement and opera. It is certainly clear that the association between the two men was neither as close nor as interactive as between Strauss and Hofmannsthal. In fact, the relationship would appear to have been far closer between the daughters and wives of the two families where correspondence is addressed in the familiar ‘Du’, whereas Wellesz and Hofmannsthal continued to address each other as ‘Sie’. In any case, Hofmannsthal either presented Wellesz with works that were already completed, or discussed treatments with Wellesz, leaving him to finish off whatever was necessary.

Opferung des Gefangenen, was the combined work of the choreographer Kurt Joos and Egon Wellesz. It was neither a true ballet nor an opera, but employed double roles for each character as both singing and dancing figures. It was premiered in Cologne in 1926

Alkestis and Achilles auf Skyros, both libretti and treatments provided by Hofmannsthal allowed Wellesz to exploit the full pageantry of the Baroque. He employed a movement chorus that was unlike anything seen on an opera stage before. The initial run of Alkestis, despite great appreciation shown by Ernst Toch, was met with considerable bewilderment by the public. Its return runs in Cologne and Stuttgart confirmed the work in the repertoire where it stayed until its removal in 1933 by the Nazis.

In 1924, Rudolf Laban, choreographer and head of the ballet at Berlin’s State Opera mounted Wellesz’s Die Nächtlingen or Those of the Night. It was choreographed by Max Terpis. The opening movement was only for percussion and there were entire movements danced without any music at all. The public had never seen anything like it and it was not a success. Yet the concepts were revolutionary and provided modern dance with opportunities it had never had, anticipating developments in ballet by many decades.

Wellesz composed another one-act opera called Scherz List und Rache, which Otto Klemperer had requested in order to have a second work to perform with Kurt Weill’s Der Protagonist. Plans came to nought and the work did not receive its premiere until 1928 in Stuttgart. It remained popular, however, and established itself in six major opera houses before its removal in 1933.

Die Bakchantinnen or the Bacchae, was premiered in Vienna’s State Opera on June 20th 1931 conducted by Clemens Kraus. It was a success with both critics and the public and Kraus’s intention of taking the work with him to Munich was thwarted by the Nazi take-over in 1933. Wellesz hammered out the libretto himself after discussions with Hofmannsthal, who since 1882 until shortly before his death had expressed a desire to rework the Pentheus myth.

Ad hoc musical events had taken place since the end of the war in 1918, such as the Mahler Festival in Amsterdam in 1920. In 1922, Wellesz, Rudolf Réti and several other Schoenberg students decided it was necessary to mount a reconciliatory music festival that brought contemporary composers from all different corners of the globe together. Initially, a chamber music festival was announced for Salzburg in 1922. With its success, it was decided to make it into an annual event and thus was founded in 1923, the International Society for Contemporary Music. Neither the Berlin nor Viennese factions would countenance the other city being the society’s headquarters so it was suggested by the American contingent to base the organisation in London. Cambridge professor Edward Dent was elected as its president.

After its first events, held in Salzburg, the organisation began to meet in different European cities, with Prague in 1924 and Venice and Prague in 1925. Other important ‘meetings’ were in Siena in 1928 and Florence in 1934. One of the most important festivals was in 1936 in Barcelona which saw the posthumous premiere of Alban Berg’s violin concerto.

Following the success of Die Bakchantinnen, Wellesz was chosen as the first Austrian composer since Joseph Haydn to receive an honorary doctorate at Oxford University. As already stated, these connections would be life-saving within only a few years. In recognition of his doctorate, Wellesz composed a cantata entitled Mitte des Lebens (Midlife) which received a fair number of international performances.

With the departure of Wellesz’s works from all of Germany’s opera and ballet ensembles in 1933, a new era approached which anticipated even greater hardships to come. Yet, initially, Wellesz seemed to have luck on his side. Invitations in 1933 to give public lectures in Britain not only helped him financially, but also consolidated his position within the British music establishment. From 1933 until 1938, he found himself at the very least, in sympathy with the new corporatist, Roman Catholic government, often referred to as Austro-Fascism, a form of ultra-right wing resistance to Hitler’s National Socialism. He composed several religious works and participated in the general wave of Catholic renewal sweeping Austria at the time. He had the further good fortune to be in Holland just as Austria was being ‘annexed’ by Hitler. He was attending performances of his Tone Poem Cycle Prosperos Beschwörungen (The Encantations of Prospero) with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter. He did not return. Connections with the Fürstenburg family brought him together with sympathetic British aristocracy until H.C. Colles and Edward Dent could relodge him at the Atnenaeum Club in London. There followed a compositional silence of five years.

The noted architect Josef Hoffmann designed an ‘artist-colony’ of villas in Kaasgraben, a leafy outskirt of Vienna. The small community became one of Vienna’s most exclusive addresses. The Welleszes moved into their Kaasgraben home in 1913 where their neighbours were amongst many others, the music publisher Emil Hertzka and the painter and stepfather to Alma Mahler, Carl Moll.

Documentation shows the difficulty of leaving Austria following the Nazi take-over and the incredible difficulty of receiving any restitution after the war. In a letter from England, Egon expresses his satisfaction at Emmy’s decision to sell the Kaasgraben villa and to join him in England where his prospects are better. Ironically, this letter was used against his post war claim of having to sell ‘under duress’. In the end, the Austrian post-war government offered a paltry £360 ‘compensation’ to the Welleszes. What is interesting, is the fact that upon writing the letter, Wellesz had no position that was comparable with his professorship in Vienna, nor does he mention the reasons for having to leave Austria. He and Emmy insisted until their dying days, that they had to leave Austria because they were ‘monarchists’. Had they been able to bring themselves to admit their Jewish origins, they may have achieved slightly better results. The Gestapo papers that requisitioned all of their belongings make only one case against Egon ‘Israel’ and Emmy ‘Sarah’ Wellesz – their Jewishness. Yet even in questions of justice, the Welleszes refused to see themselves as Jews. They saw themselves as devout Catholics. To have done otherwise would have yielded to the language of their persecutors, creating a dilemma that left them paying a heavy price for injustices.

Bruno Walter’s invitation by the Concertgebouw was to conduct two different programmes in both Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Each concert would contain a work by a living Austrian composer. As such, the invitation for the concerts, falling as it did in March 1938, saved the lives and immediate careers of Bruno Walter, Egon Wellesz and Enrst Krenek, whose piano concerto represented the other living Austrian composer. None of them would return to Austria again until after the war.

Wellesz’s ‘Prospero’ was dedicated originally to the Concertgebouw and its conductor Mengelberg. As the letter above shows us, there seems to have been some thoughts on the appropriateness of the dedication as it was apparently scratched out – whether by the publishers or the composer in light of Mengelberg’s equivocal position during the Nazi years.

Wellesz was well connected upon his unplanned arrival in London in March 1938. Initially housed by sympathetic aristocrats, he was moved by Edward Dent to the Athenaeum Club in London until H.C. Colles could secure a grant, where initially he worked on Groves Dictionary of Music – an association he kept for many years. His move to the city of Oxford was the logical consequence of his many contacts, leading to expectations that he would more easily find employment within the university.

One of Wellesz’s last works while still in Austria was his highly expressive setting of Sonnets by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, perhaps anticipating his association with England, despite the fact he offers both her name and the work in a German translation. Originally composed for soprano and string quartet, he later expanded the accompaniment to full string orchestra.

From 1938 until 1943, Wellesz stopped composing. He broke the silence with his fifth quartet, a movement of which he entitled ‘in Memoriam’. In a later explanation, he noted that the work had been composed under terrible circumstances in the darkest of times and that the title was a reference to his earlier life and earlier friendships. After the war, Karl Amadeus Hartmann would incorporate Wellesz’s ‘In Memoriam’ quartet into his new music series in Munich.

The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo was written in 1944. The text is by the British Roman Catholic poet Gerald Manley Hopkins and reflects on hope and faith. Its edgy beauty is in many ways deeply symbolic for this period of war and exile.

Wellesz had started to develop an interest in Byzantine liturgical music in 1915, at a time when this area was still totally unfamiliar to the west. Over the centuries, its notation had slowly faded from the collective musical memory. It was not until 1904 that Oskar Fleischer (1856-1933) finally established the intervallic signs using the above shown ‘Papdikai’ while remaining unable to encrypt the dynamic and rhythmic ones. Wellesz returned to study ancient thesis of Byzantine musical theory related to ‘neums’ or notational symbols. Wellesz took Fleischer’s work along with work by Jean-Baptists Thibaut (1872.1938) and established that the 6 symbols for the ascending second also showed different dynamic characteristics. As all larger intervals were shown as a compilation with a symbol for the second, there emerged six different dynamic variants. At precisely the same time, the British musicologist Henry Julius Tillyard (1881-1968) working in relative obscurity in Cardiff, came up with the same conclusion. Tillyard and Wellesz would become close associates and rather than becoming rivals, formed the Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae in 1931,which was located in Denmark under the direction of the Danish Philologist Carsten Høeg (1896-1961).

One of the few works influenced by Wellesz’s research in Byzantium was his Mirabile Mysterium op. 101 commissioned by the Austrian Radio in 1967. The work is for soloists, mixed chorus and orchestra. Wellesz uses seven of the Patriach’s Sophronios of Jerusalem’s (7th century) twelve Troparias, which announce the mystery of God becoming man on Christmas. The narrator recites the text in German parallel to the chorus, which sings in Greek.

The policy of internment was extremely controversial. It was Churchill who decided that there was no measure too extreme in fighting what many saw as Nazi Fifth Columnists posing as Jewish refugees. Until then, only ‘enemy aliens’ deemed a serious security risk had been interned. Churchill’s policy of general internment of Germans, including families of 2nd or even 3rd generation Germans, Italians and Austrians created a bizarre situation of German Nazis and Italian fascists in Great Britain at the outbreak of war, being interned together with the anti-Axis political refugees and thousands of fleeing Jews.

Over time, camp life took on its own routine. Wellesz wrote in one letter to his wife that it was like a spa, but with only men. ‘But what men!’ he goes on to write. Indeed, the cream of the German speaking intelligentsia found itself locked up together. In due course, there would be camp newspapers, and eventually, a camp university with public lectures offering such subjects as nuclear physics, or Byzantine musical notation depending on who was free and interested. Chamber music groups sprung up and there were art classes offered by the likes of Kurt Schwitters. These developments were slow in coming and dependent on the goodwill of the commanding officers.

The indignities of camp life soon became a psychological weight that resulted in Wellesz suffering a total mental breakdown. Hans Gál in his own memoirs tells of bullying and suicides. Most felt that with the fall of France, Jews were simply being rounded up in anticipation of Britain going the same way. Only after the intervention of Ralph Vaughan Williams, H.C. Colles and Edward Dent could Wellesz be returned to academic life in Oxford.

The British – as did every country except Mexico – saw Austrians, following the ‘Anschluss’ as Germans. For this reason, Austrian organisations were founded to differentiate themselves. Chief amongst them was the Austrian Centre. Though founded primarily with support from the Communist Party and funded from Moscow, it set itself up, at least overtly, as non-partisan and anti-Nazi until the Hitler Stalin pact. This was also the case with the larger German refugee cultural initiatives. In anticipation that the war would be lengthy and wishing to put doctrinal distance between refugee needs and Soviet subsidies, a number of Austrians, including the Communist Georg Knepler, help found the Anglo-Austrian Music Society.

After heavy lobbying from the Incorporated Society of Musicians (ISM), every effort was mae to keep Austrian and German musicians out of Great Britain. Once allowed to enter the country, an equally strenuous effort was made by the ISM to keep them from working. Dame Myra Hess who organised midday concerts at London’s National Gallery simply ignored this ordinance allowing many Austrian musicians rare opportunities to perform in public. As Austrians did not wish to be thought of as Germans, they formed a number of specific Austrian initiatives collectively grouped together under the ‘Free Austria Movement’ (FAM). At these various centres, they could take language courses, trace relatives, seek legal advice and so on.

As the war drew to an end, Wellesz began to reconnect with his Austrian heritage. Such an experience was not unusual. Many Austrians and Germans had stopped speaking the language ‘of the enemy’ – even in private. Correspondence was always in English due to censorship. The view that Hitler did not represent the true nature of Germanic, or Austrian culture ran deep. It was during a holiday in the Lake District, an area of England that reminded Wellesz of the lakes in Austria, that the thematic ideas first occured to him for a symphony. To write a symphony at all was already a declaration of cultural nationality. It was the uniquely Austrian musical form and had largely been abandoned by Modernist as superseded by newer, more plastic musical concepts. To return to the symphonic ideal, and to do so in its very classical form, something that differentiated his Prospero from the symphonies of Mahler and others, was a psychological confirmation of homeland.

Over the next quarter century, Wellesz would go on to compose nine symphonies along with a large torso entitled ‘Epilogue’. The first four follow strict classical structure and suggest highly condensed Bruckner in an expressive, largely tonal language. The slow movements of all of the first four symphonies offer undisguised musical homages to Mahler with music that is deeply felt and profoundly poignant. The First Symphony was premiered by the Berlin Philharmonic on the 14th of March, 1948 – exactly 10 years following the fateful ‘Anschluss’ – and conducted by Sergiu Celibidache.

There followed in rapid succession the next three symphonies – all in keeping with the first symphony’s diatonic tonality and strict classical sonata form. The Symphony no. 2 ‘die Englische’ was premiered in 1949 by Karl Rankl in Vienna with the Vienna Symphony orchestra. As with the other early symphonies, its slow movement is rhapsodic and Mahlerian while remaining distinctively Wellesz with its wide intervals and frequent use of unison.

The British conductor Adrian Boult commissioned Wellesz’s Third Symphony, only for it to be rejected by the heads of Broadcasting at the BBC. Boult, who had already conducted the Second Symphony was spineless in his defence of the commission and it remained unperformed until long after Wellesz’s death. It is one of Wellesz’s strongest works and the reasons for its BBC rejection must remain a mystery, though correspondence from Wellesz to his daughter suggests that residual chauvinism and a distaste of continental developments – especially those from Germany and Austria – may have been at the heart of the decision. Wellesz writes ‘I have shown them proof that I am now a British subject!’ Other émigrés suffered similar fates. Composers such as Berthold Goldschmidt or Karl Rankl tried, like Wellesz, to cater for English musical developments and all would suffer the indignities of public and humiliating rejections.

The Symphony no. 4 ‘Austriaca’ is the last of Wellesz’s classical symphonies, and received its premiere in 1955 in Vienna under the baton of Rudolf Moralt. Despite its name, its slow movement offers a destinct homage to Elgar through a very Central European lens:

From Symphony no. 5 onwards, Wellesz’s musical language becomes more overtly radicalised. His Fifth Symphony starts off with a 6-tone row which in the development is expanded to 12 tones. He would not return to 12-tone composition again in his subsequent four symphonies. Correspondence between Wellesz and Dr Herbert Vogg, his publisher at Doblinger, indicated that musical trends were moving sharply away from tonality and though Wellesz made great protestations that he was equally able to develop a musical idea both tonally and atonally, it appears that his first symphonic departure from tonality would logically be a return to the safety of Schoenbergian dodecaphonic writing. In other instances, he despared of the avant-garde of the 1950s and ’60s, referring to it as ‘polished one-day Modernism’.

Though Wellesz’s subsequent symphonies would become highly expressive with no tonal centre, they held to a fairly classical symmetry that meant that the careful listener would never find himself lost on a drifting sea of atonality. Repeated listening, results in Wellesz’s unique use of wide intervals and angular subjects seeping under the skin of the listener, drawing them into Wellesz’s individual, highly emotional sound world.

Only when the Arts Council of Great Britain put forward a competition for a new opera in English, with the suggestion that it would be mounted for the Festival of Britain in 1951, would Wellesz be motivated to return to music theatre. Incognita is based on a novel from 1692 by the Restoration dramatist William Congreve and adapted into an opera libretto by Elizabeth Mackenzie. Despite such British stalwarts as Malcolm Arnold, Albert Coats, Cyril Scott, Bernard Stevens and Lennox Berkeley also entering, the winning operas were composed by the émigré composers Berthold Goldschmidt with Beatrice Cenci, and Karl Rankl and his Deirdre of the Sorrows. The competition required that submissions be anonymous and when winners were revealed to be former ‘enemy aliens’, any previous suggestion that there might be staged performances were silently dropped, followed by plentiful hand-wringing by the organisers. We can safely assume that had Wellesz’s Incognita even made it to the final rounds, it would have suffered the same fate. Wellesz claimed that he and Mackenzie wrote Incognita with no specific performance goal in mind, but Lewis Foreman writing for the British Music Society pages in 2004 discovered that Wellesz had indeed entered it into the Arts Council competition. The £300 commission fee would have been very welcome, apart from any confirmation that he had not lost his dramatic talent in the intervening years. That it did not make the final rounds, let alone the final selection probably led Wellesz to claim later that he and Mackenzie had simply written the work out of admiration for the author and the subject matter. With the Oxford University Opera Club’s performance in 1951, it received a staging, thus paradoxically achieving somewhat more than the ‘winners’ Goldschmidt and Rankl.

Wellesz’s professor of musicology, Guido Adler did not die until 1941. He was cared for in his last days by his daughter Melanie Adler, and as a Jew, was ‘protected’ most likely, by contacts of Baldur von Schirach, the NSDAP Gauleiter for Vienna. Adler’s Professorship of Comparative Musicology was taken over, against his wishes, by his former student Robert Lach in 1927. Lachs joined the Nazi Party in Austria while it was still illegal in 1933. Erich Schenk, originally from Salzburg, but teaching in Rostock, was brought to Vienna as professor of musicology by Lach in 1940. Schenk wished to obtain Adler’s library upon his death and was surprised when his daughter Melanie refused to hand it over. She had already agreed with a family friend, Prof. Rudolf von Ficker, to sell the library to the University in Munich in Exchange for a modest sum of money and a document that guaranteed safe passage out of Nazi Germany. Schenk arranged for the sale to be blocked and informed the Gestapo. She was arrested and murdered in Maly Trostinez on 26th May, 1942.

Schenk was later praised in post-war Austria for having saved the library for the ‘Fatherland’, but von Ficker accused him in 1945 of obtaining it through deceit, at the price of Melonie Adler’s extermination. The evidence was damning, but Schenk was let off, claiming that it was he who had protected Adler and Melanie from deportation. Following his election as Dean of the Department of Philosophy in 1950 and as professor of musicology, Schenk blocked all attempts by students to research any of Vienna’s Jewish composers, halting at various Points, dissertations on Mahler and Schreker. In each case, his reasons were openly anti-Semitic and even reported as such in the local press. In 1957, Schenk was promoted to Rector of the University and either deliberately, or through his machinations, made it impossible for Wellesz to return. Unlike many musical refugees, Wellesz wished to be restored to his professorship in Vienna. Indeed, most would have seen him as the obvious candidate to take over Adler’s former position. It was not to be. A full outline of the Schenk-Guido Adler library episode can be obtained (in German) on the following site: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Schenk

It was not possible to ignore Egon Wellesz in Austria. His symphonies had been premiered in Vienna on a regular basis. In 1953, he was awarded Austria’s highest prize for cultural Achievement – its ‘Staatspreis für Musik’. Members of the Vienna Philharmonic requested an Octet in 1948 that could be performed as a companion work to the Schubert.

He was elected to all of the various societies and institutions that were proving useful for providing prestige rather than restitution. It’s not easy to know how he felt. Wellesz enjoyed the trappings of prestige and felt a justifiable entitlement to the recognition he was granted. It must remain unresolved if he was disappointed by his inability to realise his wish to return to his native country with his former professorship restored. Wellesz would often mention to friends how poorly informed his students at Oxford were. He was neither allowed to teach composition, nor was he ever promoted to professor. Indeed, music scholarship was considered of secondary importance to the more central task of training church organists. It was a humiliation at Oxford that Wellesz found difficult to take and impossible to understand.

Towards the end of his life, Wellesz was approached to compose a Viola concerto. All that survives of the original intention is a beautiful, and typically expressive work for solo Viola entitled ‘Präludium’, performed by Gottfried Martin on November 2nd 1972, only a week before Wellesz’s death in Oxford on November 9th.