- Profession: Textiles, Secession (member).

- Residences: Vienna.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 11-11-1863 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 18-11-1929 Vienna, Austria.

- Buried: 22-11-1929 Meidling cemetery, Vienna, Austria. Grave B-2-G60.

Although Stolba’s work came in a range of styles, the imagery for his textile work is very much based on the natural world, however stylised it may appear. The stylisation of nature has been a long and fruitful episode in human decorative history, going back to the very beginnings of the human craft system, with stylised depictions painted and engraved onto early ceramics. As an aside, it is interesting to note that ceramics was a relatively late stage in human craft development, and that woven work with natural fibres made into vessels would have come long before any form of ceramic container.

Although basketry and woven work in general would have been a vital ingredient in early human culture, it has rarely survived and therefore stone and ceramic tends to dominate our view of these early cultures, which unfortunately gives us only a partial view of their lives and culture.

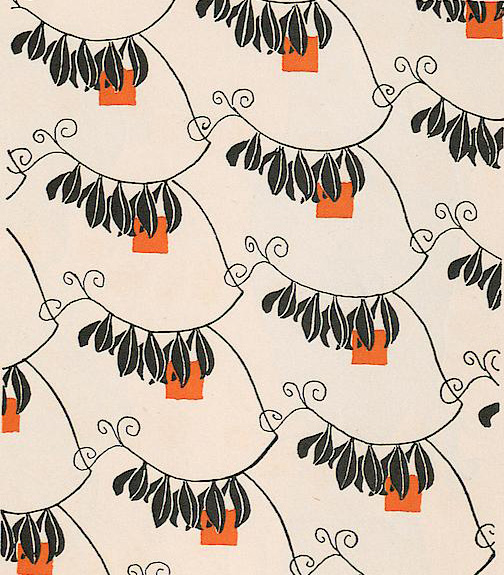

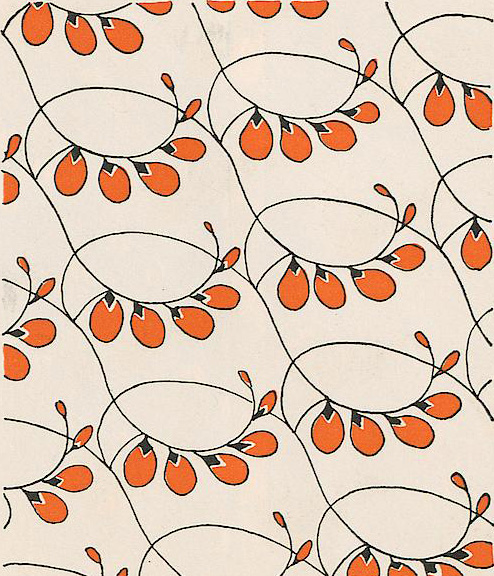

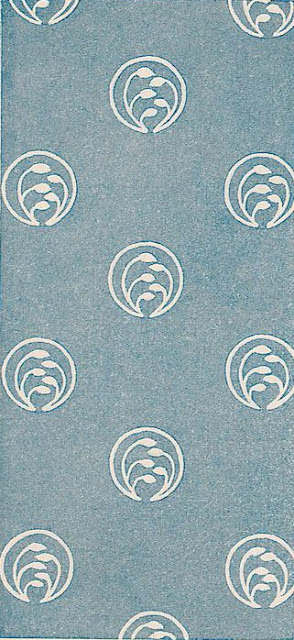

Stolba produced a number of floral interpretations, and as can be seen in these five examples, they ranged from the near representational, to the near abstract. Of course, there is an infinite supply of inspirational starting points that could eventually end up as repeatable pattern work, derived both from the natural and man-made environments, but it is to nature that Stolba found inspiration, at least for these particular decorative pieces. It is how he portrayed floral motifs that is perhaps most important, as the range shown is quite telling.

A flower for example, could conceivably be rendered directly with petals surrounding a flower-head centre in such a way that everyone immediately recognises the shape and style as a flower. However, a flower could also be rendered as four or five dots surrounding a central dot, a couple of differently coloured concentric circles, or even one circle by itself, the ultimate in paired down abstraction. Interestingly, most of these forms of abstraction would still be recognisable to most people as renditions of flowers.

We have to ask ourselves how we still refer to a seemingly random geometrically abstract motif as a flower. Is it part of our unconscious vocabulary that we can seem to easily place non-representational pattern work within the realms of nature? Even though no one has really given us any indication of parameters, we still often manage to render and understand the original inspiration of the creative designer.

Are the roots of nature still buried deep within our unconscious? Very probably. We have spent perhaps ninety-eight or ninety-nine per cent of our four million year history living so close to nature that we were literally cocooned within its framework. It has only been within the last few millennia that as a species we have begun to lose the connection with the natural world, replacing it with our own artificial and recently mechanised versions. However, it is intriguing to think that our brains still hold that four million year relationship, which far outweighs the two or three thousand years of urban man-made life of recent times.

Perhaps this helps to explain why we can easily see the connections with nature, ones that are seemingly hidden within otherwise abstract pattern work.