Transcript

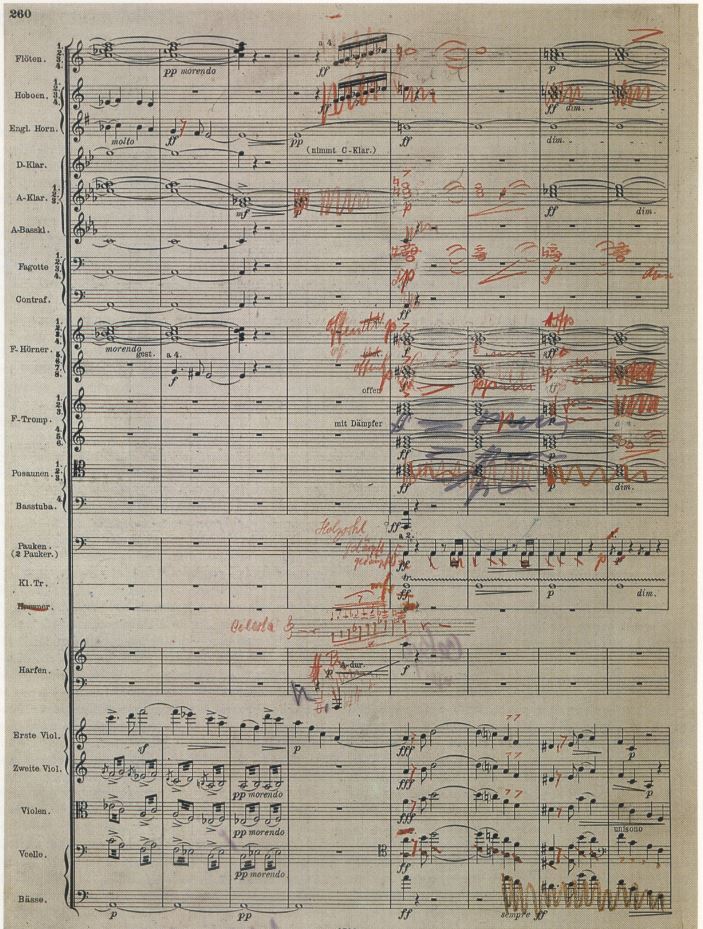

On the title page of the sketches for this movement, Mahler again poured out his grief:

The Devil dances it with me

Madness, seize me, the accursed!

Destroy me so that I may forget that I exist!

that I may cease to be

that I for…

And then it breaks off, with such an expression of deep anguish that reveals his inner demon as self tormentor. Mahler summarizes the conceptual essence of the Fourth Movement. As in so many of scherzo’s, Mahler creates a polar duality between two divergent dance themes. One raging wildly, the other joyful and carefree, abrupt alternations.

Between these two themes and their integration are also typical of Mahler’s approach to thematic development in the scherzo’s of his last period. As they become entangled in each other, these contrasting themes take on an increasingly combative posture, each struggling to overpower the other. Mahler’s cynicism is evident in his willingness to give the victory to the negative antagonist. He clearly had doubts about our ability to withstand the destructive instincts deeply embedded within us. But during his late period Mahler’s, increasing need to accept such a victory, as a natural part of life, enabled him to overcome pessimism in the finales of his last three symphonies. Since the basic premise of scherzo two is consistent with that have scherzo movements from Mahler’s earlier symphonies, it is not surprising to find that this scherzo contains many references to motives and phrases from them, rhythmic motives from the Fifth Symphony central movement, and subtle references to material from the burlesque movement of the ninth are intricately integrated into the themes presented in the second scherzo imbued with demonic mockery. Mahler combines the ferocity of the burlesque with the light-heartedness of the fifth’s middle movement, treating them as opposing forces. The raging violence of the Trinklied from Das Lied Von der Erda also permeates the first subject. Other indications of the connection between scherzo two and the Trinklied, or they’re sharing the same opening temple marking Allegro pesante and the appearance in the scherzo has a direct quotation from the Trinklied lead, in which the singer bemoans the vanity of human hopes.

Mahler also quotes motivic material from the preceding purgatorial movement, particularly the erbarme motive, with its painful expressions of a plea for redemption from tragic fate. One feels the full force of demonic fury from the very beginning yet in a schizophrenic role reversal, the trio’s gay waltz theme seems completely unaffected by the scherzo’s fuming rage. Beginning forcefully and energetically, the music keeps shifting between opposing subjects as they go round and round, caught in the grip of a wild dance macabre. Soon exhausted under the exertions of many climaxes, the first dance winds down virtually to a standstill, ending with the deadened sounds of percussion on skeletal fragments of the dance subject, a spectral representation of all the remains of this furious devil dance, almost entirely percussive and nonthematic, the closing section anticipates the endings of both Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du Soldat and Shostakovich his Fourth Symphony. When these faint percussive rhythms finally disappear, the movement ends with a forceful stroke on a muffled bass drum, on the last page of the sketches, where this shocking drum stroke appears, Mahler again writes deeply personal words that could only have been meant for his wife. “You alone know what it means,” he says, “Farewell my liar, farewell, farewell, farewell”. Other explanations are scrolled all over the page. The first line of this touching expression farewell refers to that final drum stroke.

Alma told the now-familiar story of an incident that took place outside the Mahler’s hotel room one Sunday when they were staying at the Mayfair Hotel in New York City. A funeral procession for a young fireman, who had lost his life in the line of duty was proceeding down Central Park West and hold it for a moment right under the Mahler’s window. Someone spoke a few words in the fireman’s honor, the silence that followed was broken by the sound of the single stroke of a muffled bass drum. The scene moved Mahler to tears, by incorporating this drum stroke into the 10th, his last Symphony, he undoubtedly intended to symbolize in it, the irrevocable finality of death.

Scherzo two begins with a ferocious orchestral explosion on an A minor chord with added sixth. This violent outburst shakes us awake from the dream fantasy of the purgatorial and typically Mahlerian fashion. A brief introduction presents important motivic figures that will become part of the first theme group.

– First, a falling octave in trochaic rhythm. We’ll call that motive one.

– Second, a ländler-like triadic figure in dotted rhythm, which we’ll call motive to.

Motive one recalls the importance of octaves in the Sixth Symphony, while the rhythmic configuration of motive two played a prominent role in the scherzo of the fifth. The sketches indicate that Mahler had some difficulty determining just what material this introduction should contain. But his intention to present principle motors at the outset is beyond question. To enhance the demonic character of the scherzo sections, Deryck Cooke enlarges the percussion ensemble, using xylophone glockenspiel, military drum, tom-tom triangle and router. Mahler already used these instruments in earlier scherzos to enhance the demonic nature of the music, piercing strokes on the xylophone or glockenspiel, double fragments of thematic material, making them sound audaciously arrogant. After this wild little brief introduction, the first subject enters immediately with full force, crafted from both of the introductions motives into one and two bar snippets. The first theme is thrust out furiously in the violins in Angular lines to the falling octaves of motive one and the dotted rhythm of motive two, a trumpet adds an ascending upbeat phrase that recalls the 32nd note rising upbeat figure in the sixth symphonies finale. A similar upward thrusting figure appears in the Trinklied movement of Das Lied Von der Erda and a variant of it in the second movement of the seventh symphony.

Mahler occasionally inverts this upbeat figure, four shifts it within the measure so that it begins on a strong rather than a weak beat, violins offer a variation of the first theme, in which the interval of the falling octave changes to a sixth and the dotted rhythmic figure evens out into three-quarter notes that fall stepwise extrapolating upon a counter theme heard first in the horns. A trumpet then plays its own variant of the theme, with overtones of Trinklied’s opening virtually an abbreviated version of its first theme. Following the initial statement of the first theme with variations is typical of Mahler’s technique of continuous thematic development. During the entire opening scherzo section, the music is tense and forceful. Its dynamic level remains at forte or fortissimo for all but a few moments when the music softens for the second theme, heavy accentuation, wide intervals that thrust upward or plunge downward emphatically, and thematic fragmentation, characterize the first theme in his efforts to stay within the confines of the sketches Deryck Cooke avoids the temptation of creating dense polyphony out of the scherzo material. In contrast, Clinton Carpenter adds contrapuntal lines, sometimes based upon material from other Mahler symphonies, thereby making the texture excessively dense and congested.

As the first theme continues to develop, violins inserted, typically malaria and dance figure that begins with an upward thrust of a minor seventh, and follows with a dotted rhythm. This thematic variant originates in the woodwinds as an ascending counter theme, that contrasts with the following phrases of the first subject. It also duplicates the rhythm of an important figure from the trio theme of the first scherzo and is kin to the vamp-like repeating violin figuration that introduces the vocalist at the beginning of the B section of Trinklied, oboes and English horn quote the anapestic motor B from the Purgatorio movement, while violins added to the theme, various elements of the first theme are scattered around the orchestra until the theme proper returns in second violins, with motive B now permanently lodged within it. Let’s listen from the beginning of the movement to this point in the first subject.

Horns enter assertively with a new phrase that begins with an upbeat of a rising fourth, followed by an upward arching phrase that rises on two-quarter notes and falls on a variant of motive B.

During the course of the movement, this short phrase functions like a moto akin to the erbarme motive shuttering string tremeloes in the minor mode, momentarily dark in the atmosphere. clarinets rather mildly tried to reinstate the first theme, and then a horn expands upon it. Violins offer a scherzando-like counter theme that contains the falling scalar phrase of erbarme and its dotted rhythm converted to even quarter notes, one of which is embellished with a mordant.

Together with the horns version of the first theme, the erbarme related counter theme, ushers in the second subject, played softly and plaintively by the first oboe while retaining the ländleresque, clipped dotted rhythm of the first theme. This new theme is sober, more flowing, and has little if any of its vivacity, roughness, and angularity. It recalls a thematic figure from the B flat tree when the Fifth Symphony is scherzo movement.

The second theme seems rather bemused, even melancholy. It also contains several variants of a turn figure so significant in both Der Abschied and the last two movements of the Ninth Symphony. The closing phrase of the second theme harkens back to the barman variant, which introduced it. In contrast to the first theme, the second is presented with a simple wolf speed accompaniment in pizzicato strings, that gives way to choral harmonies, muted horns intrude upon the salt strains of this following theme, with their chilling fate motive, apparently unaffected by this ominous interruption, the second theme continues, first in woodwinds, and then more hesitantly in violins. As the music builds, it becomes more assertive, as if pleading to end the wild dance just begun. On the brink of a climax, horns respond to the violin’s plea for the phrase from the second theme that sounds merciless and arrogant, reminiscent of the first theme, although it also appears to be a rhythmic variant of erbarme. This phrase begins on an upward thrusting octave leap, played at the beginning of the bar, rather than as an upbeat, it will return in the finale to mark the reappearance of the demonic spirit. In response, the full orchestra explodes with a crashing dissonance.

At the climax of this passage, violins repeat the horns fate motto against the erbarme motive, played by woodwinds and falling chromatically after an upward thrust of a super octave. This climactic passage looks both to the past into the future, it recalls the painful outpourings of the erbarme motive, and the wicked motive B from the purgatorial movement and foreshadows the fateful Return of the entire passage in the finale, also significant is the incorporation of material from the first subject as a consequence to the violin statement of the tragic motto figure. After the music calms down oboes close the square toe section with a phrase from the first subject, punctuated by trombones on the darting motive B from the purgatorial movement. Oboes pick up this demonic figure hesitatingly, adding it to their musical line, but with an elongated first note.

As the music softens the oboe theme just heard leads into the first trio, shifting to C major, the trio begins with a charming syncopated waltz theme, played softly and expressively in a dialogue between first and second violins. With its duple meter rhythm played in triple time, the trio seems to float on air propelled and first by the clarinets Calliope-like rhythmic figuration. Second violins add a hint of the scherzo’s first theme, particularly motive to the trio theme also contains the dynamic variant of erbarme that was included in the scherzo second subject, in a slight variation, first played by an oboe. Notice how this motive changes character hear it sounds gay rather than ominous as it did when asserted with great power by the horns just before the climax that occurred toward the end of the scherzo section. The trio theme contains a phrase from triply thematic and motivic elements from which pervade this music, also significant is the reappearance of a phrase from the scherzo section consisting of a triplet plus two quarter note figures. At the tail end of the trio theme, the tempo slows down briefly on a skipping upbeat phrase, played by an oboe that repeats at different parts of the bar, giving it a syncopated lilt that interjects a landler like quality. When violins take up the trio theme once more a solo violin toys with this skipping upbeat phrase, oboes and clarinets follow with a variation of the scherzo second theme that now sounds gay and carefree as it joins in the light-hearted spirit of the trio, a trumpet inserts the clipped dotted rhythm from the scherzo’s first theme, then trombones extend the variation of the scherzo second subject against shuttering string Tremeloes.

The next excerpt begins from the opening of the trio and takes us to this point.

Suddenly, the tonality shifts to E minor that dispels the carefree mood, as if a dark cloud passed over the music. The scherzo’s main tempo is reinstated as violas, cellos and bassoons. Play the trio theme with uncharacteristic power against a long, awkward arching phrase and violins, asserted with sharp accents that recall the opening of the finale of The Sixth Symphony. This phrase functions here as a brief bridge passage that leads directly into the reprise of the scherzo section.

Immediately, horns and cellos assert the scherzo’s first theme, against the arching violin phrase from the preceding bridge passage, now played by flutes and clarinets, including the piccolo E flat clarinet that enters in the middle of things and causes the rest of the phrase to shriek with horror. Oboes follow the first theme, with a second, now played strongly, but mournfully, a cello solo in high registered quotes the Trinklied phrase that had been inserted into the trio theme.

Here’s the phrase from the Trinklied movement that relates to the last part of the segment we just heard.

Isolated fragments of thematic material from the scherzo section are played by various instruments in an overlapping sequence. When separated from the second theme, its dotted rhythmic figure, played in stretched falling intervals, is reminiscent of the thrusting second theme from the first movement of the Seventh Symphony. First violins quietly but expressively intercede with the trio theme, as an English horn expands upon the first theme, but the demonic motive B from the purgatorial movement intrudes and keeps repeating, as the music builds on a crescendo toward a climax, in much the same manner as it did during the opening scherzo section, where instead of motive B the violins played falling seconds, which connote both farewell and the motive of whoa made to sound more intense by cutting off the second note of each two-note couplet. As in that earlier orchestral build-up, horns enter mightily on a dynamic variant of a fragment from the second theme that begins with an upward leap of an octave. The climax occurs on a forceful outpouring of erbarme motive but without any countervailing theme, as erbarme expands, it appears to be leading into the trio theme on strongly accented notes that build on a crescendo. This goal is confirmed when the motive telescopes into the return of the trio theme, suddenly played softly by a solo violin. We’ll begin the next excerpt from the approach to the erbarme motive that then leads to the soft Return of the trio theme, played by the solo violin.

But the reprise of the trio theme is short-lived. After only five measures, it eases up and falls helplessly into the scherzo’s principal theme on a long ascending harp glissando, stated by woodwinds against the beginning of the violins, forceful, arching phrase heard just before the scherzo reprise the sdcherzo’s theme bursts out with great force before it reaches a high point where it would begin to fall. The theme shifts gears and concentrates on elements of the scherzo’s first theme.

An oboe and clarinets soon followed by second violins, try to get the second theme back on track, once again, the music builds to a climax at which it explodes with a terrifying blast from the brass on the tragic model from the purgatorial movement that incorporates motive B, this orchestral outburst is cut short and following a short pause, the easy going trio theme returns softly.

Violins play variations of the waltz theme, while muted horns tinker with the ländler-like rhythms from the scherzo second subject, the demonic motive B has by this time become a permanent fixture in the waltz tune, as has the Trinklied phrase within screw pedal like figure played in canonic imitation.

Rhythmic figures associated with the trio present themselves in combination, the flooding waltz upbeat at leaps up by an octave, and the clipped dotted rhythm taken from the trio of the Fifth Symphony scherzo movement. Even the ascending four-note upbeat from the scherzo’s first subject, which was sourced in the six symphonies finale makes an appearance here. The waltz theme crescendos into massive orchestral outbursts on a dissonant chord that leads into a reconfigured version of the moving orchestral passage that followed the words Du aber Mensch in the Trinklied movement of Das Lied. This overpowering expression of grief is suddenly interrupted on a crescendo by the trios waltz tune, the next excerpt begins with the horns, quoting from the scherzo’s movement of the Fifth Symphony, and the rising figure from the six symphonies finale in the trumpet, both played to the rising up beats of the violins.

These constant interruptions and diversions that alternate between scherzo and trio subjects recall the incessant jockeying back and forth between march and minuet in the finale of the seventh Symphony.

When the pain slackens and the dynamic level diminishes, the music becomes restful, providing soothing relief from the tension generated by the scherzo trio rivalry. In a comforting C major, flute, harp, and strings quietly play both a broadened and inverted version of the horn call on elements of the Trinklied theme that had first appeared before the outburst of the erbarme motive that preceded the first trio section, but erbarme has lost its power, it no longer frightens, instead, it begins calmly, by rocking back and forth on a pair of falling fifths. And oboe quietly sounds motive two, which the horns pick up in extended dialogue, oboes hinted the principle was tune until the violins return exuberantly with the trio’s spirited second waltz theme.

But the wicked motive B still threatens to subvert this pleasant music. It comes in slyly as a counter theme on the horns. While the violins play the gay waltz tune in A major. A trumpet takes the waltz theme from the violins, to which an oboe responds with a variant of the flitting upbeat figure. Second violins repeat this figure, while horns cleverly try to disguise the motto phrase that now includes motive B, we hear next from the reprise of the trio themes.

Fragmentation of the second trio theme continues, with its melodic phrases set against each other in violins and horns, wider upward leaps enhance the music’s carefree spirit. We are transported to the world of the fifth symphonies middle movement, brimming over with joie de vivre and hidden within the increasingly contrapuntal web of the spirit in waltz music, are subversive motivic elements, such as the Purgatorio‘s motive B, and erbarme.

Undisguised hints of scherzo subject begin to materialize, infecting the fun-loving spirit of the trio, woodwinds interject a variant of the scherzo’s first theme, while horns add pieces of it to the waltz, particularly the falling octave, the ascending for note upbeat, and the sinister motive B from the Purgatorio. The scherzo’s brusqueness soon overwhelms the trio’s lightheartedness, and the music explodes again, on the same diminished seventh chord that opened the movement as the scherzo subject returns.

Ironically, the scherzo subject is now invaded by elements of the trio’s waltz theme. That theme seems for a moment to have won the day for it returns in D major, after a brief passage of repeating clipped dotted rhythms, akin to those appearing in the closing section that preceded the earlier reprise of the of this segment. As the waltz continues to develop, with its various elements, skillfully interwoven, it now contains some of the scherzo material and the Trinklied phrase becomes part of its melodic line. Both the ländleresque clipped dotted rhythm and the four-note upbeat figure make a noticeable appearance in horn and trumpet while the strings flit about with a light-hearted waltz upbeat, that playfully shifts position within the bar on each repetition.

Just as the waltz tries to reassert itself, a catastrophic orchestral outburst completely shatters the music’s composure with an enormous dissonant ninth chord. As the trumpets give out a scathing blast of the Purgatorio’s motive be from this shattering chord emerges a cry of despair on the erbarme motive extended by further reference to the crinkly theme, over which the trumpets repeat motive B a seventh lower. In this terrifying moment, the deep anguish of the barman phrase is ridiculed by the sarcastic disdain of motive B. The sheer terror of this passage recalls the horrific vision of the graveyard scene from the Trinklied movement made especially poignant by reference to that movement in the erbarme phrase.

This terrifying passage will return in the finale.

Soon the music softens, and the trios syncopated waltz emerges out of the erbarme phrase as if it were a natural outgrowth. When the waltz quiets down fragments of thematic and motivic material from both scherzo and trio are strung together and interrelated, casting a shadow over the music.

First, the landler like the dotted rhythm of motive two enters in mid measure on an oboe, accompanied by descending quarter note Tremeloes in the cellos and a steady waltz rhythm, played by the root of both trio themes follow the second on a pair of horns, and the first in violas, another horn duo plays the Trinklied reference. As this shadowy passage of contrasting themes continues. the horn motto reappears violins tried to resurrect the scherzo’s calming second theme on a crescendo, but it is interrupted in the same way as it had been toward the close of the first scherzo when a ranking phrase ushered in references to the Trinklied theme in the brass that ended with a powerful outcry of erbarme, this time that outcry is without any support from the horn motto, which is here played by the strings.

These orchestral outbursts seem to be merge from nowhere and bring painful reminders of mortality.

On a retard that hints at the trio’s waltz theme, the music stops for a brief pause at the height of a crescendo, and then resumes on a solo viola, tenderly playing the waltz theme. Leaping up beats from this theme played off the beat, seem to have lost their vitality, they tried to revive on a strong crescendo, but to no avail. Trumpets brusquely cast these thematic fragments aside, with an overpowering statement of the horn motto that wavers between D minor and D major, chords repeat this frightening model more haltingly, followed by two repetitions of motive to the second or third lower than the first. Once again, the music recedes from the weight and force of this painful outburst on quiet chords and horns, over descending chromatic pizzicato’s in bass strings, the atmosphere becomes frozen in stillness.

In a much slower tempo, the coda begins in the shadows, with fragments of various themes and motives played by a chamber ensemble of wins and violins. Mahler often ends has skirts or movements with a reduced orchestra playing thematic scraps that slowly die away into nothingness.

This closing section differs markedly from those of scherzo one and the scherzo of the Fifth Symphony, thematic disintegration works as a symbol for the breakdown of human life no less cynically than the triumph of decadence. In scherzo two coda, we sense that the devil dance is over, but that the demonic spirit has won the day, completely enveloping its prey.

Gradually, the dance music steals away as the orchestra deflates to a percussion ensemble, supported by low strings, and a single clarinet, cellos and basses play a steady waltz rhythm, tapping with the back of the bow on the strings as accompaniment to thematic fragments scattered among other instruments. A clarinet sheepishly flexed out the waltz is upbeat, while timpani occasionally insert molars favorite march beat on falling fourths in quickstep tempo.

In the last measures, this evanescent music builds solely on rhythmic figures that virtually evaporate until it completely disappears. When it would seem that we have reached the movements and a moment of complete silence is shattered by a powerful blow on a muffled drum effect is overwhelming.

There is some controversy about how loud this stroke should be, but the arguments for reducing the dynamic levels substantially are not worth mentioning here. So what does it portend on the last page of the sketches for this movement Mahler scrolled another note to Alma, “only you know what it means”. Its meaning will become apparent in the finale which follows without pause.

By Lew Smoley