- Year 1908.

- Year 1909.

- Period: 21-11-1908 until 10-04-1909.

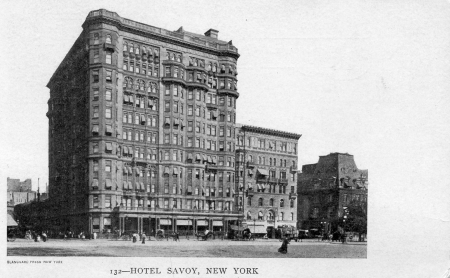

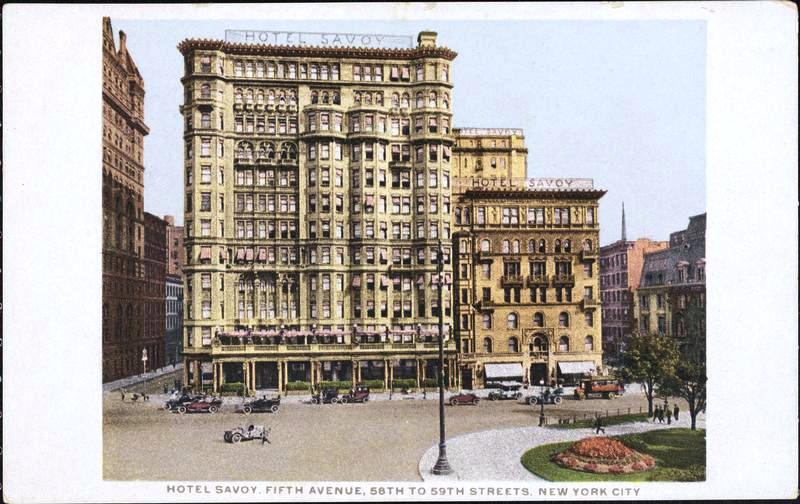

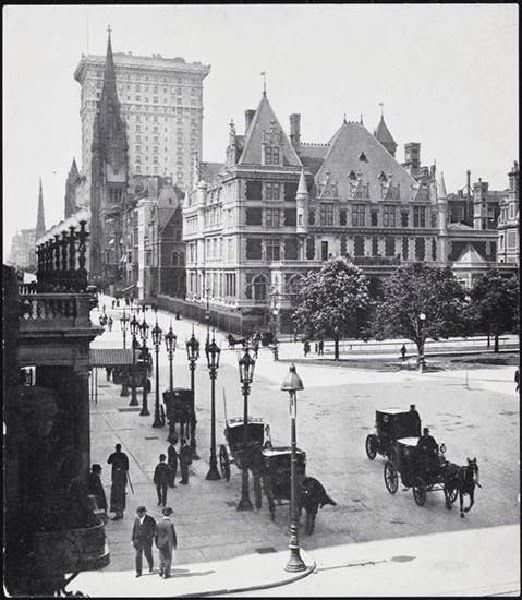

- 5th Avenue and 59th Street (767 5th Ave).

- Demolished.

The Savoy was intended to fill the block, spreading south. Instead it eventually went east. Nevertheless, it perched a Hotel Savoy sign on the adjoining building.

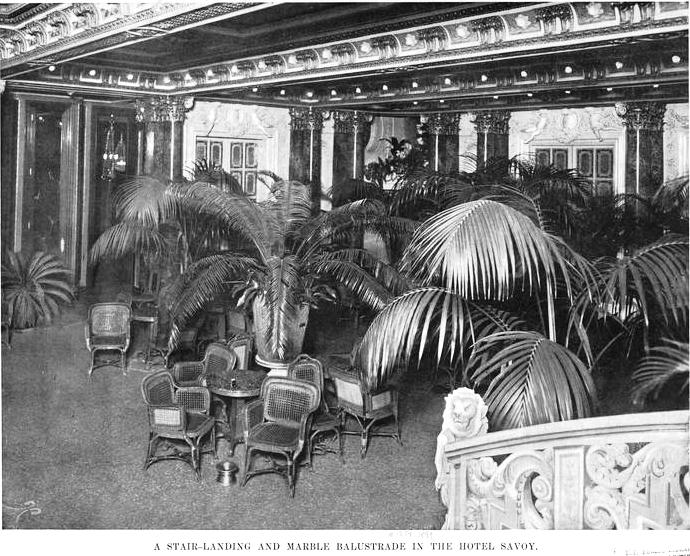

The Hotel Savoy was informally opened on June 6, 1892. Judge P. Henry Dugro had spared no expense. Construction costs were about $2 million and the decorations and furnishings of the banquet hall on the first floor alone cost $60,000. Invited guests, according to The Times the following day, “wandered through its halls and magnificently furnished and decorated rooms and admired the splendor which met their gaze at every turn.”

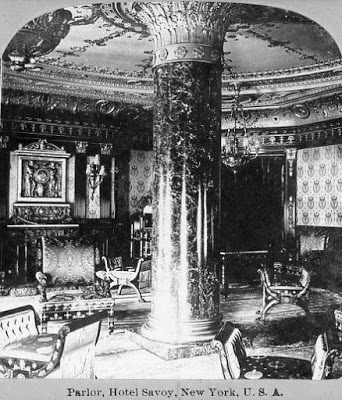

The banquet room was the showpiece of the hotel. African marble pillars, partially inlaid with Killarney green marble, upheld the ceiling with its large painting, “The Four Seaons,” by Virgilio Tojetti. Sculpted groups by Karl Bitter flanked either end of the ceiling. Satinwood wainscoting lined the walls, inlaid with mother-of-pearl and metal. Bronze figures within niches held electric lights. At the rear of the banquet room was the musicians’ gallery, its canopy upheld by Grecian caryatids. In front of the gallery was a Sienna marble fountain.

The interiors took advantage of American society’s fascination of things French. There were five public parlors on the second floor – one decorated in the Louis XIV, one in the “First Empire,” and three in Louis XVI decor. The Times reported that “The corner suite on the second floor is an exact reproduction of the rooms of Marie Antoinette in the Trianon Palace at Versailles.” The furnishings of his room reportedly cost $20,000.

As with all high-class hotels at the time, the Hotel Savoy accommodated both transient and permanent guests. Among the latter were the esteemed lawyer and former Minister to Austria, John Jay; and the wealthy David Wallace and his wife. In the depth of the night of March 31, 1894 they would be part of great excitement in the Hotel Savoy.

The hotel was outfitted with the latest in safety technology – electric fire alarms. Around 3:00 that morning a chambermaid awoke to the smell of smoke. Well-trained on emergency procedures, she did not panic, but grabbed a shoe and smashed the glass in the alarm box. Bells began to ring in every room and 350 guests were startled awake. “They arose as one man and began to act as frightened people do when there is a fire,” reported The Times.

The Fire Department was notified by phone while six policemen from the street searched for the fire with the night clerk. Some lodgers helped in the search – most rushed through the halls in various stages of dress to the ground floor. “One young man rushed there wearing a lace curtain which had been hanging in his room. Another appeared in an evening-dress coat, a silk hat, and a pair of black stockings. Other toilets ranged from a pair of shoes and a nightdress to a full suit of clothes,” said The Times. The fire was discovered in a closet. While buckets of water were poured on the blaze, John Jay, seriously ill, was carried to the ground floor. One person who was not perturbed by the fire was David Wallace, whose apartments were near the fire. “Mr. Wallace partially dressed himself and stepped into the hall. People were rushing about, screaming and gesticulating. Mr. Wallace saw that a closet was afire, but that there were many men, with plenty of water, there to attend it. He went back to his room, told Mrs. Wallace not to rise, undressed, and went back to bed, leaving those who wished to catch cold in their scanty attire in the corridors.” The fire was quickly extinguished and the major damage, other than to the woodwork, was to the water-soaked carpeting.

A little over a month later, on May 5, 1894, John Jay died in his rooms at the Hotel Savoy. His condition dated to September 1890 when he was run over by a cab near Grand Central Station. “The accident resulted in the general breaking up of Mr. Jay’s vigorous constitution,” explained The Times. He had moved into the Savoy in the autumn of 1893.

The Hotel Savoy continued to compete with the Plaza for notable guests and residents. In October 1894 the Savoy was home to international opera star Madame Nellie Melba. The diva suffered through an attack of influenza here that year.

Over a decade after its completion the Hotel Savoy had not lost its high-class stature. In 1907 the yearly rental for a “beautifully furnished” suite of a parlor, three bedrooms and three baths was $4,000 – around $8,700 per month in 2015 terms.

It was the sort of rent that only families like that of Charles N. Fowler could afford. He lived here in 1911 with his wife and five-year old daughter. Their apartment was the scene of a mysterious robbery on January 19 that had all the marks of an inside job. According to The Evening World the following day, Mrs. Fowler and her daughter were alone in the apartment. After lunch, Mrs. Fowler removed her $1,000 diamond horseshoe brooch and placed it on a table in the sitting room. She reclined on the sofa there and fell asleep, awakening around 5:00 to find the brooch missing.

The cultured residents of the Hotel Savoy would have a brush with the less-tony class on June 6, 1920. Frances Levy was the daughter of Lower East Side apparel manufacturer Joe Levy, known locally as the “Duke of Essex Street.” The dress and suit maker had garnered a small fortune and was determined that his daughter would be married in style to Harry Levine. “From all accounts nothing is to be left undone to make this one of the distinctly notable weddings of the year,” advised the New-York Tribune a few weeks ahead of the ceremony, “and the beauty and chivalry of the lower east side will have a day to remember.” Joe Levy was equally determined to outdo Fifth Avenue in cost and display. “The east side hears that Miss Levy’s wedding gown is to cost $5,000.” reported the newspaper. “The ‘Duke,’ it is understood, will wear an eight-carat diamond stud, among other things.”

On December 9, 1922 the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that “Negotiations are about to be concluded for the sale of the Hotel Savoy.” The sale would be just the first in a rapid-fire string. Real estate operator Frederick Brown purchased the building for $3.75 million. Only a few days later he sold it to the du Pont family. It then became property of the Savoy Hotel Corporation, which resold it in May 1925 to the Childs Restaurant chain for $6.5 million. The New York Times reported “the Childs Company said that they contemplated making extensive improvements on the site. This was interpreted as meaning that a modern building will be erected.”

Within a week of the sale, on May 25, a public auction liquidated the “furniture, carpets, draperies, silver, china, glassware, pictures and statuary.” On November 28 that year demolition was announced.