Friedrich Klopstock (1724-1803).

- Profession: Poet.

- Residences: Leipzig, Copenhagen.

- Relation to Mahler: Inspiration for “Die Auferstehung” (Symphony No. 2). Movement 5: “Aufersteh’n”. Im Tempo des Scherzos. Wild herausfahrend.

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 02-07-1724 Quedlinburg, Germany.

- Died: 14-03-1803 Hamburg, Germany.

- Buried: Christian’s church, Hamburg, Germany.

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock was a German poet. His best known work is his epic poem Der Messias (“The Messiah”). His service to German literature was to open it up to exploration outside of French models. Klopstock was born at Quedlinburg, the eldest son of a lawyer. Both in his birthplace and on the estate of Friedeburg on the Saale, which his father later rented, he spent a happy childhood; and more attention having been given to his physical than to his mental development, he grew up strong and healthy and became an excellent horseman.

In his thirteenth year, he returned to Quedlinburg and attended the Gymnasium there, and in 1739 went on to the famous classical school named Schulpforta. Here he soon became an adept in Greek and Latin versification, and wrote some meritorious idylls and odes in German. His original intention of making Henry the Fowler the hero of an epic was, under the influence of Milton’s Paradise Lost with which he became acquainted through Bodmer’s translation, abandoned in favor of a religious epic.

While still at school, he had already drafted the plan of Der Messias on which most of his fame rests. On 21 September 1745 he delivered, on quitting school, a remarkable “departing oration” on epic poetry—Abschiedsrede über die epische Poesie, kultur- und literargeschichtlich erläutert—and next proceeded to Jena as a student of theology, where he elaborated the first three cantos of the Messias in prose. Having found life at this university uncongenial, he transferred in the spring of 1746 to Leipzig, where he joined the circle of young men of letters who contributed to the Bremer Beiträge. In this periodical the first three cantos of Der Messias in hexameter verse were anonymously published, in 1748.

A new era in German literature had commenced, and the identity of the author soon became known. In Leipzig he also wrote a number of odes, the best known of which is An meine Freunde (1747), afterwards recast as Wingolf (1767). He left the university in 1748 and became a private tutor in the family of a relative at Langensalza, where unrequited love for a cousin (the “Fanny” of his odes) disturbed his peace of mind.

For that reason he gladly accepted in 1750 an invitation from Bodmer, the translator of Paradise Lost, to visit him in Zürich, where Klopstock was initially treated with every kindness and respect and rapidly recovered his spirits. Bodmer, however, was disappointed to find in the young poet of the Messias a man of strong worldly interests, and a coolness sprang up between the two friends.

At this juncture Klopstock received from Frederick V of Denmark, on the recommendation of his minister Count von Bernstorff (1712–1772), an invitation to settle in Copenhagen with an annuity of 400 thalers in the hope that he would complete Der Messias there. The offer was accepted.

On his way to the Danish capital, Klopstock met in Hamburg the woman who in 1754 became his wife, Margareta (Meta) Möller, the “Cidli” of his odes. She was the daughter of a Hamburg merchant and an enthusiastic admirer of his poetry. His happiness was short; she died in 1758, leaving him almost broken-hearted. His grief at her loss finds pathetic expression in the fifteenth canto of the Messias.

The poet subsequently published his wife’s writings, Hinterlassene Werke von Margareta Klopstock (1759), which give evidence of a tender, sensitive and deeply religious spirit. See also Memoirs of Frederick and Margaret Klopstock (English translation by Elizabeth Smith, London, 1808) and her correspondence with Samuel Richardson, published 1818.

Klopstock now relapsed into melancholy; new ideas failed him, and his poetry became more and more vague and unintelligible. He continued to live and work in Copenhagen, however, and next, following Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg, turned his attention to northern mythology, which he conceived should replace classical subjects in a new school of German poetry. In 1770, when King Christian VII dismissed Count Bernstorff from office, he retired with the latter to Hamburg but retained his pension together with the rank of councillor of legation.

Here, in 1773, he issued the last five cantos of the Messias. In the following year he published his strange scheme for the regeneration of German letters, Die Gelehrtenrepublik (1774). In 1775 he traveled south, and making the acquaintance of Goethe on the way, spent a year at the court of the margrave of Baden at Karlsruhe. Thence, in 1776, with the title of Hofrath and a pension from the margrave, which he retained along with that from the king of Denmark, he returned to Hamburg where he spent the remainder of his life. His latter years he passed, as had always been his inclination, in retirement, only occasionally relieved by socializing with his most intimate friends, occupied in philological studies and taking scant interest the in new developments in German literature.

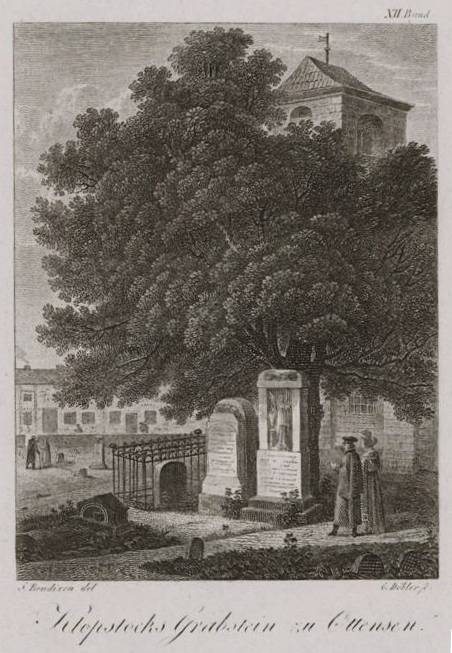

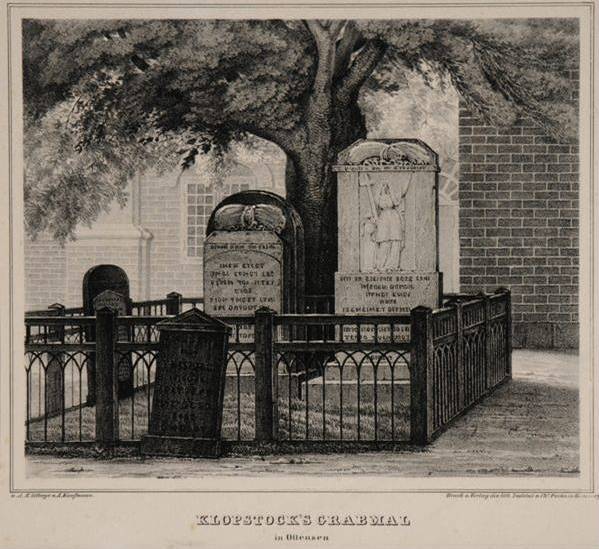

The American War of Independence and the French Revolution aroused him to enthusiasm, however. The French Republic sent him a diploma of honorary citizenship; but, horrified at the terrible scenes the Revolution had enacted in the name of liberty, he returned it. At sixty-seven he undertook his second marriage, to Johanna Elisabeth von Winthem, a widow and a niece of his late wife, who for many years had been one of his most intimate friends. He died in Hamburg on 14 March 1803, mourned by all Germany, and was buried with great pomp and ceremony next to his first wife in the churchyard of the village of Ottensen.

Goethe in his autobiography recorded his personal impression of Klopstock: “He was of small stature, but well built. His manners were grave and decorous, but free from pedantry. His address was intelligent and pleasing. On the whole, one might have taken him for a diplomatist. He carried himself with the self-conscious dignity of a person who has a great moral mission to fulfil. He conversed with facility on various subjects, but rather avoided speaking of poetry and literary matters.”

His enrichment of the poetic vocabulary and his attention to prosody were of great service to the poets that immediately followed him. In freeing German poetry from the exclusive reign of the Alexandrine verse, he was the founder of a new era in German literature. Schiller and Goethe were artistically indebted to him.

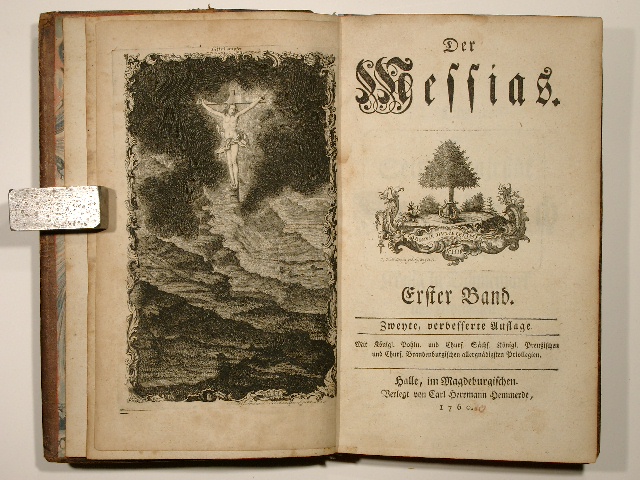

Der Messias

Klopstock’s nature was best attuned to lyrical poetry, and in it his deep, noble character found its truest expression. He was less suited for epic and dramatic representation; for, wrapt up in himself, a stranger to the outer world, without historical culture, and without even any interest in the events of his time, he was lacking in the art of plastic representation such as a great epic requires. Thus the Messias, despite the magnificent passages which especially the earlier cantos contain, cannot satisfy the demands such a theme must necessarily make. The subject matter, the Redemption, presented serious difficulties to adequate epic treatment.

The Gospel story was too scanty, and what might have been imported from without and interwoven with it was rejected by the author as profane. He had accordingly to resort to Christian mythology; and here again, circumscribed by the dogmas of the Church, he was in danger of trespassing on the fundamental truths of the Christian faith. The personality of Christ could scarcely be treated in an individual form, still less could angels and devils; and in the case of God the Father, it was impossible.

The result was that, despite the groundwork—the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Revelation of St John, and the model ready to hand in Milton’s Paradise Lost—material elements are largely wanting and the actors in the poem, divine and human, lack plastic form. That the poem took twenty-five years to complete could not but be detrimental to its unity of design; the original enthusiasm was not sustained until the end, and the earlier cantos are far superior to the late ones.

Thus the intense public interest the work aroused in its commencement had almost vanished before its completion. It was translated into seventeen languages and led to numerous imitations.

Odes

In his odes Klopstock had more scope for his peculiar talent. Among the best are An Fanny; Der Zürchersee; Die tote Klarissa; An Cidli; Die beiden Musen; Der Rheinwein; Die frühen Gräber, Mein Vaterland. His religious odes mostly take the form of hymns, of which the most beautiful is Die Frühlingsfeier. His dramas, in some of which, notably Hermanns Schlacht (1769) and Hermann und die Fürsten (1784), he celebrated the deeds of the ancient German hero Arminius, and in others, Der Tod Adams (1757) and Salomo (1764), took his materials from the Old Testament; are essentially lyrical in character and deficient in action. He immortalized his 1750’s visit at the Swiss Au peninsula in his Ode an den Zürichsee (“Ode to Lake Zurich”).

Gustav Mahler

It was hearing Friedrich Klopstock (1724-1803)‘s hymn “Die Auferstehung” at the funeral of Hans von Bulow (1830-1894) in 1894 that gave Gustav Mahler the inspiration for the final movement of his Symphony No. 2. Mahler incorporated the hymn with extra verses he wrote himself to bring a resolution to this mighty problematic work.

Klopstock grave (Graveyard Christian’s church, Hamburg)

Friedrich Klopstock (1724-1803).

Friedrich Klopstock (1724-1803).