“My music is always the voice of nature sounding in tone…”

“The Bohemian music of my childhood home has found its way into many of my compositions.”

Exercise as Inspiration

Mahler was a great health enthusiast, including physical activity in many forms. His love of outdoor exercise is reflected musically in the fifth movement of his Fifth Symphony. The rhythmic and melodic contours evoke the rolling contours of the countryside.

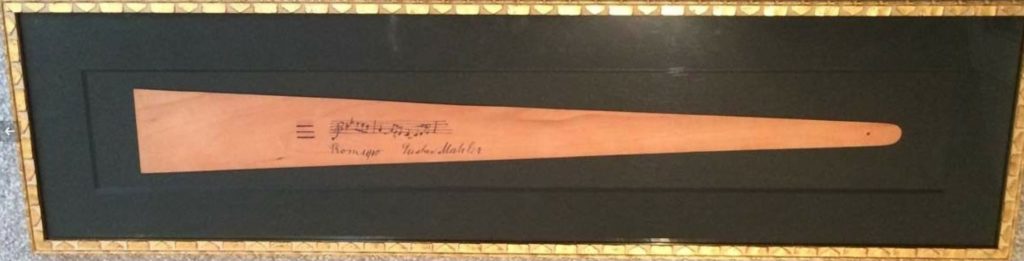

Sometimes exercise was a direct source of inspiration. “I made up my mind to finish the Seventh, both Andantes of which were then on my table. I plagued myself for two weeks until I sank into gloom … then I tore off to the Dolomites… I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head — and in four weeks, the first, third, and fifth movements were done.”

Echoes Across the Landscape

The effect of the landscape on the experience of sound is a feature of the scherzo of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. Here he creates echoes as though resounding from mountaintop to mountaintop.

Similarly evocative portraits of the landscape can be found in his Sixth Symphony. A serene landscape provides relief from the grim march of the first movement of his Sixth Symphony.

Nature as Metaphor

Nature was not only a source of inspiration for Mahler; it could function as a nature as a metaphor for human emotion. In a setting of a poem by Friedrich Rückert, “Do Not Look into My Songs” (Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder), nature in the form of bees represents the artist at work: “Bees who are building their cells don’t allow themselves to be observed, nor do they watch themselves.”

A particularly touching example of nature as metaphor for human emotions occurs in one of the songs from the Kindertotenlieder (Child Death Songs) collection, also on poetry by Friedrich Rückert. The singer laments the decision to send children out into the weather; the stormy music also reflects the condition of the singer’s heart and soul: “In this weather, in this wind, I would never have sent the children out! They were carried, carried out! I wasn’t allowed to say anything about it!”

Two Kinds of Marches

Mahler’s Fifth Symphony opens with a fanfare that instructs us to “pay attention” before it moves into a funeral march. We hear echoes of this fanfare at the end of movement.

In Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, the first movement march is now more of a universal expression, divorced from its military origins.

Marching to the Abyss

Mahler’s Sixth Symphony represents his most profound exploration of grief. It begins with a ruthless march that evokes the desperation and violence of a forced march in wartime.

Mahler had laid a foundation for this music in the last setting he made of a Wundehorn poem, Revelge. In this song, a soldier watches his comrades fall:

Ah, brother, I can’t carry you.

The enemy has beaten us down!

May God help you!

Tralali, tralalei, tralalera,

I must march to my death!

Critics reacted strongly to the work. Julius Korngold, a supporter of Mahler, compared the music to painting: “There is a painter in Vienna who compares to Mahler in his contrapuntal confusion of instrumental lines and his challenges to the Philistines: Klimt. But Klimt does not have the pathos, the driving energy, the painful stirring of nerves.”

Marching to Salvation

Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, dubbed “Symphony of a Thousand” because of its massive performing forces (orchestra, chorus, soloists, and children’s chorus), features a collection of “impetuous” marches in the first part, which is based on the hymn Veni creator spiritus.

The development of these marches borders on parody.

Symphonic Chorales

The end of the second movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony evokes the sounds of church chorales. The music reflects a particularly productive period in his life, when his job at the Vienna Court Opera allowed him the resources to build a home in Maiernigg, where he conceived the Fifth Symphony.

A dramatic chorale marks the climax one of Mahler’s settings of the poetry of Friedrich Rückert. In “Midnight,” (Um Mitternacht), the narrator suffers isolation and doubt until the final verse: “At midnight I put my strength in your hands: Lord of death and life, you keep the watch at midnight.”

Spiritual and Earthly Love

The fourth movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, the Adagietto, has been his most popular music since its premiere. The music is portrait of Mahler’s love for his new wife, Alma. As the delicate music suggests, Mahler’s conception of earthly love shared the essential qualities of spiritual love.

Mahler also created a musical portrait of Alma in the soaring second theme of his Sixth Symphony. In her memoirs, she recalled: “After he had conceived the first movement, Mahler came down out of the forest and said: ‘I’ve tried to capture you in a theme – as for whether I’ve succeeded, I don’t know. You will have to tolerate it.’”

Transcendence through God and the Eternal Feminine

Mahler’s Eighth Symphony represented Mahler’s expression of transcendance. The first movement is based on the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus. “The Spiritus Creator took hold of me and drove me on for the next eight weeks until my greatest work was done.” As Alfred Roller reported, “after a rehearsal of the Eighth in Munich, [Mahler] called out cheerfully, ‘look, this is my Mass.'” The photo at right is from that rehearsal.

The second part of the Eighth Symphony is based on Faust and represents transcendence through “The Eternal Feminine” (das Ewig-Weibliche). Mahler connected the liturgical and literary texts in the third stanza of the hymn: “Accende lumen sensibus, Infunde amorem cordibus!” (“Kindle our Reason with Light. Infuse our hearts with Love!”).

A Giddy Dance

The Scherzo (the third movement) of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony is built on the rhythm of the Austrian folk waltz, or Ländler. He described the effect of the music: “Every note is charged with life, and the whole thing whirls around in a giddy dance.”

Critic Maximilian Muntz scoffed at this movement: “Waltz and Ländler motifs, robbed of their naïve innocence and cheekily made-up in modern orchestral colors, whirl around in a contrapuntal cancan.”

Mahler’s command of counterpoint was rooted in his study of the past, but he used it in a uniquely expressive way. Essential to the effect was clarity of line: “In true polyphony the themes run side by side quite independently, each from its own source to its own particular goal and as strongly contrasted to one another as possible, so that they are heard quite separately.”

In the second movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, five separate parts lend colors of pain (trumpets), defiance (horns), and struggle (strings), as the music tumbles towards a climax of despair.

In this exuberant fugal passage from the Fifth Symphony’s Finale, Mahler uses his skill in part-writing to recall the pure joy of the lively polyphonic music of the Baroque masters. The theme itself could be straight out of Bach or Vivaldi.

Sounds & Folkways

The second and fourth movements of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony are marked “Night Music” (Nachtmusik), and the entire work is sometimes called Song of the Night. In the fourth movement, Mahler evokes the tradition of a nocturnal serenade as if recalled through the haze of memory.

This cinematic passage from the second movement of the Seventh Symphony starts with a passage of woodwind solos, built from stylized versions of bird calls. Imagine how the approach of the night watch (in tuba and bassoon) agitates a flock of birds at night: they noisily take flight and scatter; then all is quiet again.

In the second “Night Music” of the Seventh Symphony, Mahler brings mandolin and guitar into the ensemble, marrying the unmistakable sound of a lover’s serenade to the symphony orchestra. Like sparkles of moonlight on a dark surface, these plucked sounds stand out against the otherwise dark colors employed in this movement.

The rocking motion of a lullaby, a cradle song, is the ironic background to a father’s remembering his daughter in “When Your Mother Comes Through the Door” (Wenn dein Mütterlein) from the Songs on the Deaths of Children (Kindertotenlieder): “When your mother comes through the door with the shimmering candle, it seems to me you always come in with her, scurrying behind just as before, into the room. Oh you, the too quickly, too quickly extinguished happy glow of your father’s cell!”

A Romp

Mahler ends his Seventh Symphony with a kind of “romp” that builds on a number of popular dance styles, beginning with the polka. Then a minuet breaks into the zany energy.

Intensity

Mahler’s Jewish identity was a subject of much discussion among his contemporaries. The melodic shapes and intensity of expression were often cited as evidence.

Intensity could border on the histrionic, as in the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, when the tinny sound of a small band suddenly interrupts the solemn cortege.

Introspection

Mahler’s sense of being an outsider shaped the emotional quality of his music. The third movement of his Sixth Symphony is perhaps the most poignantly musical introspection he ever wrote.

In one of Mahler’s settings of poetry by Friedrich Rückert, “I am lost to the world” (Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen) the voice gently disappears into the instruments, perfectly expressing the text’s expression of the end of isolation through art:

I am dead to the world’s tumult

and I rest in a quiet place!

I live alone in my heaven,

in my love, in my song.

Mahler called Anton Bruckner his “forerunner”. In the use of the Ländler in his colossal slow movements, and even in his transitions between keys, the elder Austrian composer foreshadowed several of the musical and aesthetic preoccupations of the younger one. Here are extracts from the slow movements of the Sixth Symphonies of both composers.

Mahler often lets us in on the creation of a lyrical idea by giving us the first two notes of a phrase, then three, and eventually the whole musical thought. In this piano introduction to a song on a poem by Fredrich Rückert, “I am Lost to the World” (Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen), this sequence evokes the quality of introspective thought.

Mahler turned to the poetry of Friedrich Rückert (1788 – 1866) for two important song collections: Songs on the Deaths of Children (Kindertotenlieder)and the five settings collectively titled simply Rückert Songs (Rückert-Lieder). Mahler felt a deep aesthetic kinship with the poet’s imaginative and imagistic vocabulary, moreover, both artists were attracted to Oriental sources. Mahler himself had written a student essay on the influence of the Orient on German literature and later turned to Chinese poetry for his last great song-symphony The Song of the Earth (Das Lied von der Erde).

Embedded memories

The Scherzo of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony is full of parodic depictions of the kind of “outsider” music that critics and the public deplored. It is a musical equivalent of the distorted memories that Freud discussed a few years earlier: “Our childhood memories show us our earliest years not as they were but as they appeared at the later periods when the memories were aroused.”

The Seventh Symphony is difficult to categorize. Both light and dark moods reflect Mahler’s aesthetic preoccupation with the night; in particular, the atmospheric nature of the three middle movements prompted Bruno Walter to comment that the work returned to a kind of romanticism he thought Mahler had moved beyond.

At one grotesque point in the Scherzo of the Seventh Symphony, the cellos and basses dispense with pitches altogether.