- Fragment (Audio, English, duration 02:32): Alma Mahler (1879-1964) about Gustav Mahler (and Gustave Charpentier (1860-1956)‘s “Louise”).

- Fragment (Audio, German, duration 14:23): Alma Mahler (1879-1964) about the trophies in her house and about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Interview by Jimmy Berg in House Alma Mahler New York 1952-1964 (120 East 73d Street), New York.

- Fragment (Video, German, duration 00:56) Alma Mahler (1879-1964) and Agnes Ida Gebauer (1895-1977) arriving at Tulln airport, Vienna (1947, Brumowski Air Base).

All fragments and more on You Tube page Gustav Kaliste.

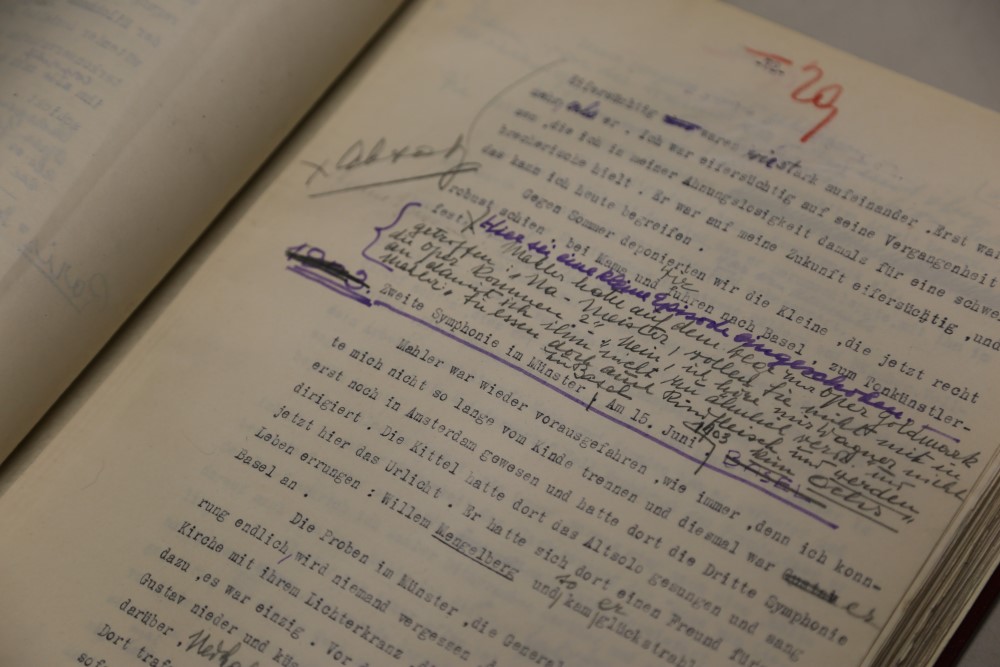

1940 (published). Alma Mahler (1879-1964): “Gustav Mahler: Erinnerungen and Briefe“. Published by Allert de Lange, Amsterdam. Diary. About: Year 1903, 1903 Concert Basel 15-06-1903 – Symphony No. 2, Hermine Kittel (1879-1948) and Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951). Page 71 in print. Médiathèque Musicale Mahler.

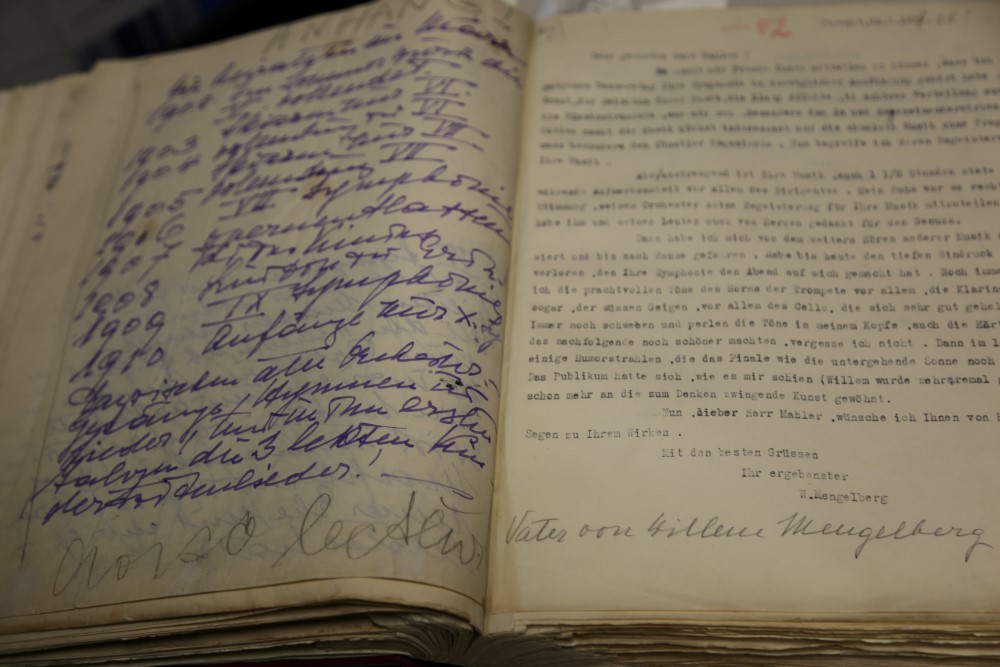

Probably 24-10-1903 (and not 24-03-1904): Utrecht, Netherlands. Letter by Friedrich Wilhelm Mengelberg (1837-1919), father of Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951) to Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). 1940 (published). Alma Mahler (1879-1964): “Gustav Mahler: Erinnerungen and Briefe“. Published by Allert de Lange, Amsterdam. About concert 1903 Concert Amsterdam 22-10-1903 – Symphony No. 3. Left side: Remarks Alma Mahler. Page 262 in print. Year 1903. Médiathèque Musicale Mahler.

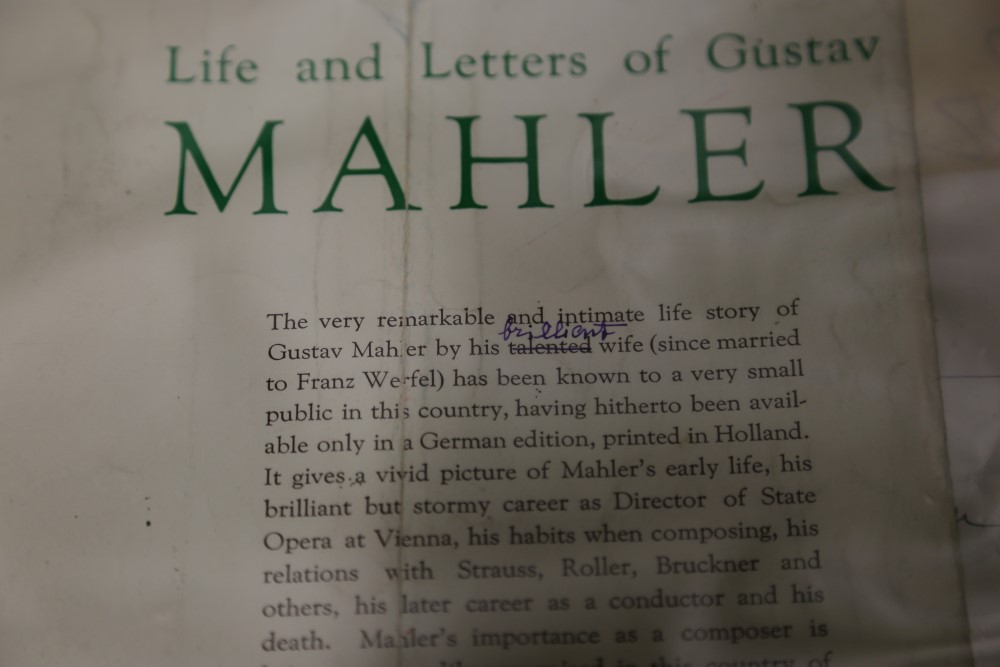

Alma Mahler (1879-1964): “Life and letters of Gustav Mahler”. Annotation by Alma Mahler (1879-1964).

Rewriting history by Alma Mahler

The Alma problem is an issue of concern to musicologists, historians and biographers who deal with the lives and works of Gustav Mahler and his wife Alma.

Alma Mahler (ultimately Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel) was not only an articulate, well-connected and influential woman, but she also went on to outlive her first husband by more than 50 years. For half a century, therefore, she was the principal authority on the mature Mahler’s values, character and day-to-day behavior, and her two books quickly became the central source material for Mahler scholars and music-lovers alike.

Unfortunately, as scholarship has investigated the picture she sought to paint of Mahler and her relationship with him, her accounts have increasingly been revealed as unreliable, false, and misleading, and evidence of deliberate manipulation and falsification can no longer be ignored. The fact that these deeply flawed accounts have nevertheless had a massive influence – leaving their mark upon several generations of scholars, interpreters and music-lovers, and becoming a foundation of the critical and popular literature on Mahler – constitutes the ‘Alma Problem’.

Letters, correspondence

The ‘Alma problem’ manifests itself in several dimensions. To begin with, there is her treatment of the couple’s correspondence. Of the more than 350 written communications Mahler is known to have written to her, Alma suppressed almost 200 – and of the 159 that she did choose to publish, she is now known to have made unacknowledged alterations to no fewer than 122. On three occasions Alma even manufactured items by joining together separate letters. She also appears to have systematically destroyed everything that she wrote to her husband: the text of only a single one of her own letters, written before they were married, is known to survive.

As for the changes she secretly made in his letters before publication, a clear pattern can be discerned: Alma seems determined to present herself as a powerful, potent person whose tremendous gifts and personal allure placed her at the very center of events – at the same time as insisting that her selfless devotion to her husband made her the powerless, guiltless victim of his unreasonableness.

Thus her deletion of Mahler’s references to the presents he bought or offered her protected her claims that he hardly ever gave her gifts; while her deletion of his references to the plentiful sums of money he handed over to her allowed her to maintain that he had kept her short of housekeeping money.

Her deletion of references to people close to Mahler but not liked by her permitted her to minimize their apparent role in his life, compared to hers. And on other occasions she seems to have been anxious to create the impression that Mahler thought she might be merely unwilling to do or be something, rather than actually unable: his “Answer … if you are able to follow me” is secretly modified to “Answer … if you are willing to follow me”.

On this subject, Jonathan Carr has noted: “If the text (of a letter) offended Alma’s self-esteem or predilections then it had to be ‘corrected’ with some judicious deletion or insertion before the world could be allowed to see it”. In some cases her deletions have actually proved impossible to correct: her distinctive violet ink has obliterated the original word, line or passage.

Memories

Alma’s rewriting of history extends back beyond the start of her life with Mahler. She describes her father as coming “from old patrician stock”, and her mother as having been sent to Vienna to take voice-lessons with a highly regarded teacher at a private academy. It is now known, however, that Alma’s father was the great-grandson of a scythe-smith from the Steyr Valley -mand that her mother became a singer only after an early life that had seen her family flee to escape bankruptcy and the young girl herself working as a ballet dancer (at the age of eleven), a nanny, an au pair girl, and a cashier at the public baths.

Alma’s story of her ‘first meeting’ with Mahler (in 11-1901, at a dinner party given by Berta Zuckerkandl and attended by other glittering personalities such as Gustav Klimt and Max Burckhard, is one of her most famous, but it departs from the truth in at least one major respect: it was not, in fact, their first meeting. Alma is now known to have met Mahler two years earlier in the more humdrum context of a bicycle ride in the lake region of the Salzkammergut. In her diaries, she wrote: “He soon overtook us, and we met four or five times. Each time he struck up a conversation, staring hard at me”.

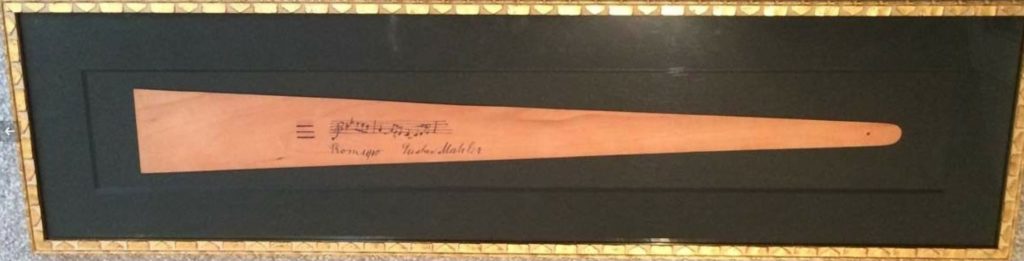

It is now known that Alma, deeply infatuated with the famous and distant figure, had previously sought (and eventually obtained) Mahler’s autograph on a postcard, and that on their actual first meeting she was embarrassed that he appeared to have “perceived the connection” between her and the card he had signed. (This story is instructive in that it not only casts light on Alma’s motivations in expunging an important fact from the record, but also reveals the value of her original diaries in correcting her later accounts. The diaries were published only in the 1990s, having remained in almost unreadable manuscript during her lifetime.)

Many of Alma’s submissions concern purely private experiences that plainly can have left no documentary evidence; nor is there any ‘balancing’ material from the other side of the marriage- for, in contrast to Alma, Mahler never wrote or spoke (except, perhaps, to Freud) about their relationship. In such circumstances, it is important to remember that the picture we have of Mahler as the typical fin-de-siècle artist – an ‘ascetic’; a morbid and tormented neurotic; a despairing and sickly man for whom all pleasures were suspect; and a man whose constant overwork undermined an already weak physical constitution – derives entirely from Alma’s writings, and is not corroborated by others. For most of his adult life, in fact, Mahler actively enjoyed putting his strength and endurance to the test: he loved to swim long distances, climb mountains, take endless walks, and go on strenuous bicycle tours.

Even in the winter of 1910-1911, when the shock of Alma’s infidelity had threatened to overwhelm him, he was still planning for his old age, and making decisions about the construction and decoration of a new house in the Semmering mountains – while in 1911, in what was probably his last interview, he made the following statement: “I have worked really hard for decades, and have born the exertion wonderfully well”.

Other evident manipulations and falsifications concern the people with whom the couple came into contact.

Symphony No. 5 and Symphony No. 6

Alma met Mahler during the period in which the Fifth Symphony was being composed (1901-1902); her various remarks and recollections concerning this and the Sixth Symphony (1903-1904, rev. 1906) provide a concise demonstration of the ‘Alma Problem’.

Symphony No. 5

In ‘Memories and Letters’, Alma writes of attending a 1904 ‘reading rehearsal’ of the as-yet unperformed Symphony No. 5: “I had heard each theme in my head while copying the score, but now I could not hear them at all! Mahler had overscored the percussion instruments and side-drum so madly and persistently that little beyond the rhythm was recognizable. I hurried home sobbing. … For a long time I refused to speak. At last I said between my sobs: ‘You’ve written it for percussion and nothing else’. He laughed, and produced the score. He crossed out the side drum in red chalk and half the percussion instruments too. He had felt the same thing himself, but my passionate protest turned the scale.” (Alma Mahler-Werfel, ‘Memories and Letters’, p.73)

Speaking of what he calls ‘this engaging story’ – which is found quoted in countless books and programme-notes – Colin Matthews explains that “the evidence of the manuscript and the printed scores does not, unfortunately, bear it out. In fact, the first edition of the score actually has very slightly more percussion in the first movement … than the manuscript…” (Colin Matthews, ‘Mahler at Work’, p.59)

Symphony No. 6

Symphony No. 6: Movement 1: ‘Second subject’

Alma claims that Mahler told her in 1904 that he had tried to ‘capture’ her (the word she reports him using is ‘festzuhalten’) in the F major theme that is the ‘second subject’ of the symphony’s first movement. The story has become canonic – to the extent that no commentator can fail to repeat it, and few listeners can hear the theme without thinking of Alma’s report. The report may of course be true (in that Mahler may actually have attempted to describe her in music, or may merely have chosen to claim that he had); but her statement is not corroborated.

Symphony No. 6: Movement 2 and Movement 3: Order of the middle movements

The long-running dispute over the ‘proper’ order of the symphony’s two middle movements – Scherzo/Andante or Andante/Scherzo – appears to be a problem for which Alma is entirely responsible. Mahler’s original score (manuscript and first published edition, as well as Zemlinsky’s piano duet arrangement) placed the Scherzo second and the Andante third; but during rehearsals for the work’s first performance the composer decided that the slow movement should precede the scherzo, and he instructed his publishers C.F. Kahnt to begin production of a ‘second edition’ of the work with the movements in that order, and meanwhile to insert a printed instruction in all existing scores.

This revised, ‘second thoughts’ ordering was observed by Mahler in every one of the three performances he gave; it is how the second edition of the symphony was published; and it is how the work was performed by others in the three additional performances that the work received during the composer’s lifetime.

In 1919, however, Alma sent a telegram to Mengelberg which said ‘First Scherzo, then Andante’. Though she provided no support of any kind for the idea that Mahler had ever wanted the movements to revert to their ‘original’ ordering, her status as ‘Mahler’s widow’ meant that conductors increasingly felt that there was some ‘authority’ for placing the Scherzo second.

The issue eventually spread to record companies (who soon proved they were not beyond taking a performance recorded with one ordering and releasing it with the other) and scholarly editors – though, again, no evidence in support of the ‘third thoughts’ ordering has ever been presented.

Symphony No. 6: Movement 3: Scherzo/children

Alma asserts that in the Scherzo movement Mahler represented the unrhythmic games of the two little children, tottering in zig-zags over the sand. Ominously, the childish voices became more and more tragic, and died out in a whimper.

This memorable (and interpretatively potent) revelation is still encountered in writings about the symphony – in spite of the fact that it is not merely uncorroborated, but is conclusively refuted by the chronology: the movement was composed in the Summer of 1903, when Maria Anna Mahler (born 11-1902) was less than a year old, and when Anna Justine Mahler (born 07-1904) had not even been conceived.

Symphony No. 6: Movement 4: Third hammer blow

Alma also claims that Mahler described the three hammer-blows of the finale as ‘three blows of fate, the last of which fells (the hero) as a tree is felled’. Deciding that the hero was Mahler himself, and that the symphony was ‘prophetic’, she then identified these three blows with three later events in her husband’s life: his ‘forced resignation’ from the Vienna State Opera; the death of his eldest daughter; and the diagnosis of a fatal heart condition.

In addition, she claims that Mahler eventually deleted the third hammer-blow from the score out of sheer superstition, in an (unsuccessful) attempt to stave off a third disaster in his own life. Again, the story has become canonic; but the difficulties it presents are several.

- Alma’s programmatic interpretation is not corroborated by the composer or any other source.

- Mahler’s resignation from the Opera was not, in reality, ‘forced’, and was not necessarily even a ‘disaster’.

- Alma exaggerates the seriousness of her husband’s ‘heart condition’, which was not inevitably fatal.

- She neglects to mention that Mahler’s discovery of her own infidelity was a ‘blow’ of far greater weight than at least one (and possibly two) of the other events she does mention.

- Her story once again falls foul of the known chronology: Mahler revised the symphony in the Summer of 1906 – whereas all three of the events reported by Alma took place after this time: Mahler requested release from his Vienna Opera contract in 05-1907, and it was in July of that year that his daughter died and his heart condition was diagnosed.

- Her report of Mahler’s ‘superstitious’ reason for removing the third hammer-blow not only has no corroboration of any kind, but also betrays an ignorance of the musical sources. Mahler originally notated no fewer than five large percussive impacts in the score of his finale (b.9, b.336, b.479, b.530, b.783); these five were later reduced to a ‘classically’ dramatic three and specifically allotted to a ‘Hammer’ – though with one of these blows (the last) occurring in a structural and gestural context that makes it very different from the other two (and equivalent to the two that were removed). It was this anomalous blow that Mahler, in revising the work, chose to delete – making the important question not ‘Why did he finally take it out?’, but ‘Why did he first leave it in?’

Selected further examples

Alma claims that on 24-02-1901 she attended two different musical events conducted by her future husband. “I heard him conduct twice that day”, she reports. She then gives an eye-witness account of the second of these events, supposedly a performance of Die Meistersinger:

“He looked like Lucifer: white in the face, his eyes like black coals. I felt profoundly sorry for him, and said to the people sitting near me: ‘This is more than the man can endure’. … It was the unique intensity of his interpretative art that enabled him to create two such miracles in one day without destroying himself”.

This entire story is pure invention, however. The work that Mahler is known to have conducted on that occasion was actually Mozart’s The Magic Flute; and, in any case, Alma’s diaries show that she remained at home all that evening.

Alma claims that Mahler ‘feared women’, and that he had almost no sexual experience right up to his forties (he was 41 when they met). In fact, Mahler’s long record of prior romantic entanglements – including a lengthy one with Anna von Mildenburg – suggests that this was not the case.

Alma claims that her new husband was 50,000 gold crowns in debt due to the extravagance of his sister (and housekeeper) Justine, and that only her own careful budgeting allowed this to be repaid. In fact, no amount of wifely thrift could ever have paid off a debt of such a size, as the sum was far in excess of Mahler’s gross income as opera director, salary and ‘fringe benefits’ combined.

Alma claims that Mahler intensely disliked Richard Strauss’s opera ‘Feuersnot’, that he ‘had a horror of the work’, and avoided conducting it. In fact, Feuersnot is the only Strauss opera that Mahler is known to have conducted (see ‘Gustav Mahler – Richard Strauss Correspondence, 1888–1911, Ed. Herta Blaukopf (London, 1984)).

Describing a 1904 concert in Amsterdam in which Mahler’s Symphony No. 4 was performed twice, Alma claims that Mahler, after conducting the work in the first half, handed the baton to Mengelberg for the evening’s second performance. “Mahler took a seat in the stalls and listened to his work”, she claimed. “Later, when he came home, he told me it had been as if he himself had conducted. Mengelberg had grasped his intentions down to the last nuance”. Her claim is entirely false. From the contents of a postcard that Mahler wrote to her before the performance; from the printed programme for the event, and from the various newspaper reviews, we know that Mengelberg did not conduct at the concert: the two performances that were given were both conducted by Mahler.

Problems in translation

An important aspect of the ‘Alma Problem’ for which Alma herself might not have been responsible concerns the ‘standard’ English translations of her books, which frequently differ significantly from the German originals.

‘Memories and Letters’ (Basil Creighton’s 1946 version of ‘Erinnerungen und Briefe’) incorporates material that was apparently added at that time and is not found in the German edition, and also shows a tendency to abridge and revise (especially where the original was frank about sexual matters).

For example, the words Alma recalls as her invitation to the dinner at which she claims she met Mahler for the first time can be literally translated as follows: “Mahler will be coming to us today. Don’t you want to be there too? – I know you are interested in him’. Creighton, however, merely renders it as: ‘We’ve got Mahler coming in tonight – won’t you come?’

Recounting the story of the couple’s journey to St Petersburg, Alma writes in German of her husband suffering a ‘frightful migraine’ on the train, and describes the condition as ‘one of those auto-intoxications from which he suffered all his life’. Yet this is rendered by Creighton as Mahler catching ‘a severe feverish chill’, and the statement that he ‘suffered all his life from these infections’.

Describing the discovery of Mahler’s heart condition, Alma speaks of the diagnosis of ‘hereditary, although compensated, valve defects on both sides’. Creighton’s English translation (along with all the commentaries that derive from it) omits the reference to the defects being ‘compensated’.

Faced with this and other problematic translations, Peter Franklin has been moved to ask whether there might not be ‘a special, English readers’ Mahler, idiosyncratically marked and defined by textual tradition’.

Relevant quotations

- Jonathan Carr: “It is now plain that Alma did not just make chance mistakes and ‘see things through her own eyes’. She also doctored the record”.

- Henry-Louis de La Grange: “the most serious distortions of the truth … are those which were deliberately introduced and fostered by (Mahler’s) wife”.

- Hugh Wood: “Often she is the only witness, and the biographer has to depend on her while doubting with every sentence her capacity for telling the truth. Everything that passed through her hands must be regarded as tainted”.