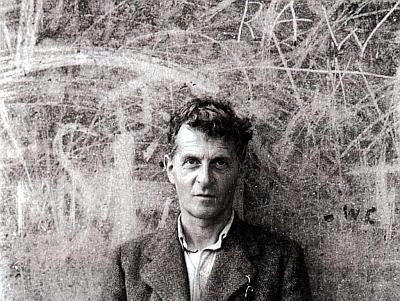

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

- Profession: Philosopher.

- Residences: Vienna, Cambridge.

- Relation to Mahler:

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 26-04-1889 Vienna, Austria.

- Died: 29-04-1951 Cambridge, England.

- Buried: Graveyard of the chapel for Ascension Parish Burial Ground off Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, England. The graveyard was previously known as St. Giles Cemetery in association with the parish of St. Giles church at the bottom of Castle Hill.

More

- Son of Karl Wittgenstein (1847-1913).

- Brother of Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961).

Ludwig “Lucki” Josef Johann Wittgenstein was an Austrian-British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. From 1929–1947, Wittgenstein taught at the University of Cambridge. During his lifetime he published just one slim book, the 75-page Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), one article, one book review and a children’s dictionary. His voluminous manuscripts were edited and published posthumously. Philosophical Investigations appeared as a book in 1953 and by the end of the century it was considered an important modern classic. Philosopher Bertrand Russell described Wittgenstein as “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived; passionate, profound, intense, and dominating”.

Born in Vienna into one of Europe’s richest families, he inherited a large fortune from his father in 1913. He gave some considerable sums to poor artists. In a period of severe personal depression after the first World War, he then gave away his entire fortune to his brothers and sisters. Three of his brothers committed suicide, with Wittgenstein contemplating it too. He left academia several times—serving as an officer on the front line during World War I, where he was decorated a number of times for his courage; teaching in schools in remote Austrian villages where he encountered controversy for hitting children when they made mistakes in mathematics; and working as a hospital porter during World War II in London where he told patients not to take the drugs they were prescribed while largely managing to keep secret the fact that he was one of the world’s most famous philosophers. He described philosophy, however, as “the only work that gives me real satisfaction.”

His philosophy is often divided into an early period, exemplified by the Tractatus, and a later period, articulated in the Philosophical Investigations. The early Wittgenstein was concerned with the logical relationship between propositions and the world and believed that by providing an account of the logic underlying this relationship, he had solved all philosophical problems. The later Wittgenstein rejected many of the assumptions of the Tractatus, arguing that the meaning of words is best understood as their use within a given language-game. Wittgenstein’s influence has been felt in nearly every field of the humanities and social sciences, yet there are diverging interpretations of his thought. In the words of his friend and colleague Georg Henrik von Wright:

He was of the opinion… that his ideas were generally misunderstood and distorted even by those who professed to be his disciples. He doubted he would be better understood in the future. He once said he felt as though he was writing for people who would think in a different way, breathe a different air of life, from that of present-day men.

1903–1906: Realschule in Linz

Wittgenstein was taught by private tutors at home until he was fourteen years old. Subsequently, for three years, he attended a school. After the deaths of Hans and Rudi, Karl relented, and allowed Paul and Ludwig to be sent to school. Waugh writes that it was too late for Wittgenstein to pass his exams for the more academic Gymnasium in Wiener Neustadt; having had no formal schooling, he failed his entrance exam and only barely managed after extra tutoring to pass the exam for the more technically oriented K.u.k. Realschule in Linz, a small state school with 300 pupils. In 1903, when he was 14, he began his three years of formal schooling there, lodging nearby in term time with the family of a Dr. Srigl, a master at the local gymnasium, the family giving him the nickname Luki.

On starting at the Realschule, Wittgenstein had been moved forward a year. Historian Brigitte Hamann writes that he stood out from the other boys: he spoke an unusually pure form of High German with a stutter, dressed elegantly, and was sensitive and unsociable. Monk writes that the other boys made fun of him, singing after him: “Wittgenstein wandelt wehmütig widriger Winde wegen Wienwärts” (“Wittgenstein strolls wistfully Vienna-wards due to adverse winds”). In his leaving certificate, he received a top mark (5) in religious studies; a 2 for conduct and English, 3 for French, geography, history, mathematics and physics, and 4 for German, chemistry, geometry and freehand drawing. He had particular difficulty with spelling and failed his written German exam because of it. He wrote in 1931: “My bad spelling in youth, up to the age of about 18 or 19, is connected with the whole of the rest of my character (my weakness in study).”

Faith

Wittgenstein was baptized as an infant by a Catholic priest and received formal instruction in Catholic doctrine as a child. It was while he was at the Realschule that he decided he had lost his faith in God. He nevertheless believed in the importance of the idea of confession. He wrote in his diaries about having made a major confession to his oldest sister, Hermine, while he was at the Realschule; Monk writes that it may have been about his loss of faith. He also discussed it with Gretl, his other sister, who directed him to Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. As a teenager, Wittgenstein adopted Schopenhauer’s epistemological idealism. However, after his study of the philosophy of mathematics, he abandoned epistemological idealism for Gottlob Frege’s conceptual realism. In later years, Wittgenstein was highly dismissive of Schopenhauer, describing him as an ultimately “shallow” thinker: “Schopenhauer has quite a crude mind… where real depth starts, his comes to an end”.

Wittgenstein’s faith would undergo developmental transformations over time, much like his philosophical ideas; his relationship with Christianity and religion, in general, for which he professed a sincere and devoted reverence, would eventually flourish. Undoubtedly, amongst other Christian thinkers, Wittgenstein was influenced by St. Augustine, with whom he would occasionally converse in his Philosophical Investigations. Philosophically, Wittgenstein’s thought shows fundamental alignment with religious discourse. For example, Wittgenstein would become one of the century’s fiercest critics of Scientism

With age, his deepening Christianity led to many religious elucidations and clarifications, as he untangled language problems in religion, attacking, for example, the temptation to think of God’s existence as a matter of scientific evidence. In 1947, finding it more difficult to work, he wrote, “I have had a letter from an old friend in Austria, a priest. In it he says that he hopes my work will go well, if it should be God’s will. Now that is all I want: if it should be God’s will.” In Wittgenstein’s Culture and Value, it is found, “Is what I am doing [my work in philosophy] really worth the effort? Yes, but only if a light shines on it from above.” His close friend Norman Malcolm would write, “Wittgenstein’s mature life was strongly marked by religious thought and feeling. I am inclined to think that he was more deeply religious than are many people who correctly regard themselves as religious believers.” At last, Wittgenstein writes, “Bach wrote on the title page of his Orgelbuechlein, ‘To the glory of the most high God, and that my neighbour may be benefited thereby.’ That is what I would have liked to say about my work.”

Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger (1880–1903)

While a student at the Realschule, Wittgenstein was influenced by Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger’s 1903 book Geschlecht und Charakter (Sex and Character). Weininger (1880–1903), who was also Jewish, argued that the concepts male and female exist only as Platonic forms, and that Jews tend to embody the platonic femininity. Whereas men are basically rational, women operate only at the level of their emotions and sexual organs. Jews, Weininger argued, are similar, saturated with femininity, with no sense of right and wrong, and no soul. Weininger argues that man must choose between his masculine and feminine sides, consciousness and unconsciousness, Platonic love and sexuality. Love and sexual desire stand in contradiction, and love between a woman and a man is therefore doomed to misery or immorality. The only life worth living is the spiritual one—to live as a woman or a Jew means one has no right to live at all; the choice is genius or death. Weininger committed suicide, shooting himself in 1903, shortly after publishing the book. Many years later, as a professor at Cambridge, Wittgenstein distributed copies of Weininger’s book to his bemused academic colleagues. He said that Weininger’s arguments were wrong, but that it was the way in which they were wrong that was interesting.

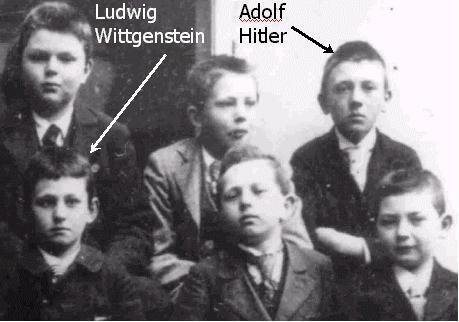

Jewish background and Hitler

There is much debate about the extent to which Wittgenstein and his siblings, who were of 3/4 Jewish descent, saw themselves as Jews, and the issue has arisen in particular regarding Wittgenstein’s schooldays, because Adolf Hitler was at the same school for part of the same time. Laurence Goldstein argues it is “overwhelmingly probable” the boys met each other: that Hitler would have disliked Wittgenstein, a “stammering, precocious, precious, aristocratic upstart …”. Other commentators have dismissed as irresponsible and uninformed any suggestion that Wittgenstein’s wealth and unusual personality may have fed Hitler’s antisemitism, in part because there is no indication that Hitler would have seen Wittgenstein as Jewish.

Wittgenstein and Hitler were born just six days apart, though Hitler had been held back a year, while Wittgenstein was moved forward by one, so they ended up two grades apart at the Realschule. Monk estimates they were both at the school during the 1904–1905 school year, but says there is no evidence they had anything to do with each other. Several commentators have argued that a school photograph of Hitler may show Wittgenstein in the lower left corner, but Hamann says the photograph stems from 1900 or 1901, before Wittgenstein’s time.

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) and Adolf Hitler.

In his own writings Wittgenstein frequently referred to himself as Jewish, at times as part of an apparent self-flagellation. For example, while berating himself for being a “reproductive” as opposed to “productive” thinker, he attributed this to his own Jewish sense of identity, writing: “The saint is the only Jewish genius. Even the greatest Jewish thinker is no more than talented. (Myself for instance).” While Wittgenstein would later claim that “[m]y thoughts are 100% Hebraic”, as Hans Sluga has argued, if so, “his was a self-doubting Judaism, which had always the possibility of collapsing into a destructive self-hatred (as it did in Weininger’s case) but which also held an immense promise of innovation and genius.”

1906–1913: University

He began his studies in mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Charlottenburg, Berlin, on 23 October 1906, lodging with the family of professor Dr. Jolles. He attended for three semesters, and was awarded a diploma on 5 May 1908. During his time at the Institute, Wittgenstein developed an interest in aeronautics. He arrived at the Victoria University of Manchester in the spring of 1908 to do his doctorate, full of plans for aeronautical projects, including designing and flying his own plane. He conducted research into the behavior of kites in the upper atmosphere, experimenting at a meteorological observation site near Glossop. He also worked on the design of a propeller with small jet engines on the end of its blades, something he patented in 1911 and which earned him a research studentship from the university in the autumn of 1908.

It was at this time that he became interested in the foundations of mathematics, particularly after reading Bertrand Russell’s The Principles of Mathematics (1903), and Gottlob Frege’s Grundgesetze der Arithmetik, vol. 1 (1893) and vol. 2 (1903) Wittgenstein’s sister Hermine said he became obsessed with mathematics as a result, and was anyway losing interest in aeronautics. He decided instead that he needed to study logic and the foundations of mathematics, describing himself as in a “constant, indescribable, almost pathological state of agitation”. In the summer of 1911 he visited Frege at the University of Jena to show him some philosophy of mathematics and logic he had written, and to ask whether it was worth pursuing. He wrote: “I was shown into Frege’s study. Frege was a small, neat man with a pointed beard who bounced around the room as he talked. He absolutely wiped the floor with me, and I felt very depressed; but at the end he said ‘You must come again’, so I cheered up. I had several discussions with him after that. Frege would never talk about anything but logic and mathematics, if I started on some other subject, he would say something polite and then plunge back into logic and mathematics.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) handwriting.

Arrival at Cambridge

Wittgenstein wanted to study with Frege, but Frege suggested he attend the University of Cambridge to study under Russell, so on 18 October 1911 Wittgenstein arrived unannounced at Russell’s rooms in Trinity College. Russell was having tea with C. K. Ogden, when, according to Russell, “an unknown German appeared, speaking very little English but refusing to speak German. He turned out to be a man who had learned engineering at Charlottenburg, but during this course had acquired, by himself, a passion for the philosophy of mathematics & has now come to Cambridge on purpose to hear me.” He was soon not only attending Russell’s lectures, but dominating them. The lectures were poorly attended and Russell often found himself lecturing only to C. D. Broad, E. H. Neville, and H. T. J. Norton. Wittgenstein started following him after lectures back to his rooms to discuss more philosophy, until it was time for the evening meal in Hall. Russell grew irritated; he wrote to his lover Lady Ottoline Morrell: “My German friend threatens to be an infliction.”

Russell soon came to believe that Wittgenstein was a genius, especially after he had examined Wittgenstein’s written work. He wrote in November 1911 that he had at first thought Wittgenstein might be a crank, but soon decided he was a genius: “Some of his early views made the decision difficult. He maintained, for example, at one time that all existential propositions are meaningless. This was in a lecture room, and I invited him to consider the proposition: ‘There is no hippopotamus in this room at present.’ When he refused to believe this, I looked under all the desks without finding one; but he remained unconvinced.” Three months after Wittgenstein’s arrival Russell told Morrell: “I love him & feel he will solve the problems I am too old to solve … He is the young man one hopes for.” The role-reversal between him and Wittgenstein was such that he wrote in 1916, after Wittgenstein had criticized his own work: “His criticism, ‘tho I don’t think he realized it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw that he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy.”