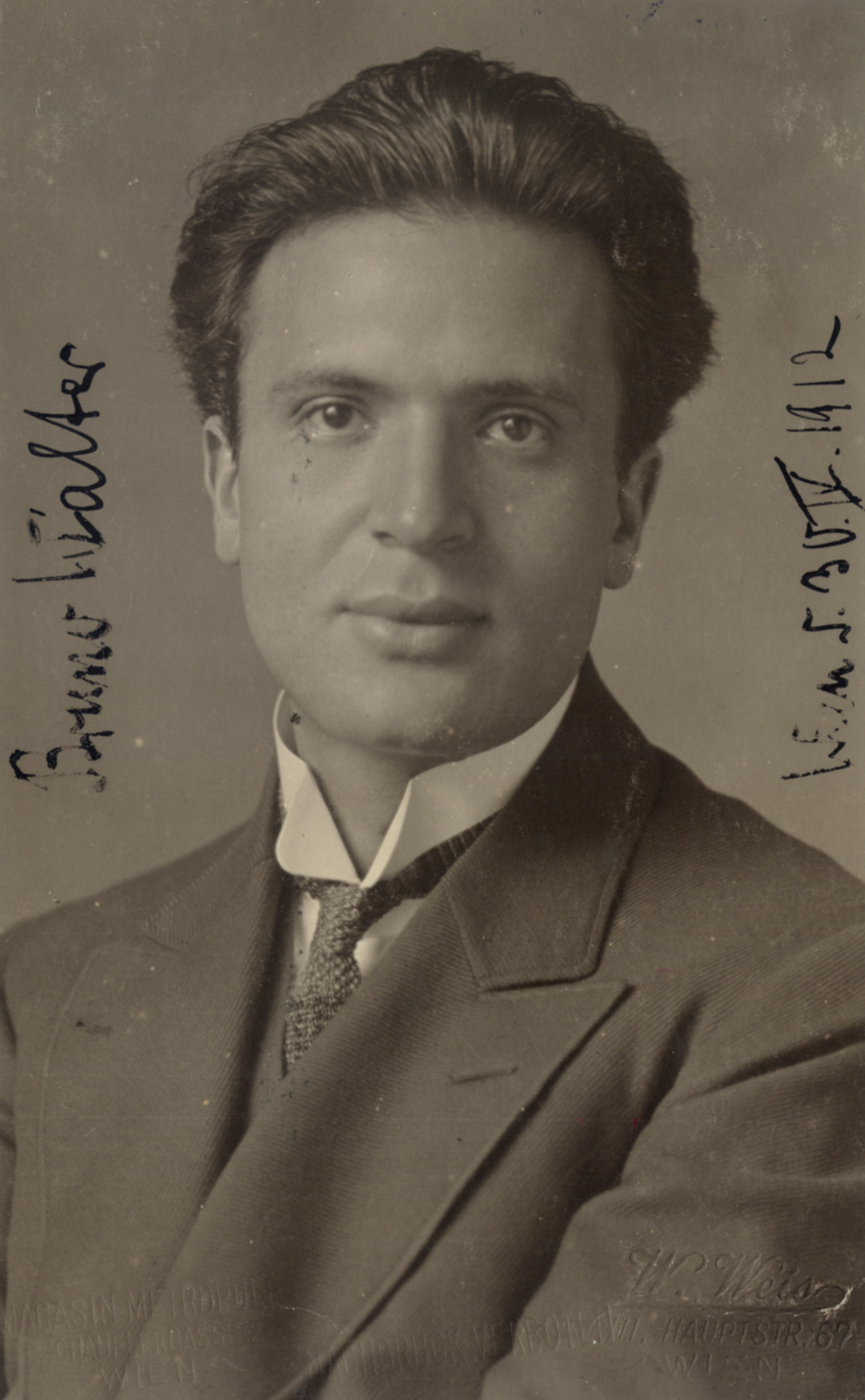

1912. Bruno Walter (1876-1962).

- Profession: Pianist, conductor.

- Residences: Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg, New York, Beverly Hills.

- Relation to Mahler: Friend, Pernerstorfer Circle (member). Worked with Gustav Mahler in Hamburg 1894-1896 and from 1901 in Vienna.

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 18-12-1898, Year 1898.

- 06-06-1911, Year 1911, letter to Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938).

- Born: 15-09-1876 Berlin, Germany as Bruno Schlesinger.

- Marriage: Elsa (Else) Wirthschaft (born 1871, died 26-03-1945, aged 74). Also: Elsa (Else) Korneck (maiden name).

- Address: 1901: Neustiftgasse, Vienna.

- 1907 consulted Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

- Daughter 1: Gretel Marguerite Neppach-Walter (1906-1939). Murdered 21-08-1939 in Berlin. She fell in love with baritone Ezio Pinza and was murdered by her jealous husband, Robert Neppach, who then killed himself.

- Daughter 2: Lotte Lindt-Walter (1910-1970).

- Died: 17-02-1962 Beverly Hills, America. Bruno Walter died of a heart attack in his Beverly Hills home in 1962.

- Buried: Abbondio Cemetery, Ticino, Switzerland.

- Audio fragment: Bruno Walter speaks about Gustav Mahler.

- See also: Bruno Walter Collection (New York).

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger) was a German-born conductor, pianist, and composer. Born in Berlin, he left Germany in 1933 to escape the Third Reich, settling finally in the United States in 1939. He worked closely with Gustav Mahler, whose music he helped establish in the repertory, held major positions with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Salzburg Festival, Vienna State Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Staatsoper Unter den Linden and Deutsche Oper Berlin, among others, made recordings of historical and artistic significance, and is widely considered one of the great conductors of the 20th century.

Early life

Born near Alexanderplatz in Berlin to a middle-class Jewish family, he began his musical education at the Stern Conservatory at the age of eight, making his first public appearance as a pianist when he was nine; he performed a concerto movement with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1889 and a full concerto with them in February, 1890.

Photo: Bruno Walter (1876-1962) alone [J. van Ronzelen -Berlin]. Inscribed and signed on back [“Fraulein Emma Mahler zur freundlichen Erinnerung an ihren treu ergeben Bruno Schlesinger”]. Emma Marie Eleanor Rose-Mahler (1875-1933). Short romance in 1895.

Photo: Bruno Walter (1876-1962) alone, in profile [Hamburg -Benque & Kinderman]. Inscribed on back [“Fraulein Emma Mahler zur Erinnerung an gemeinsam schöne Stunden zugeeignet von”] and signed on front [“Bruno Schlesinger”]. Emma Marie Eleanor Rose-Mahler (1875-1933). Short romance in 1895.

He studied composition at Stern with Robert Radeke (de:Robert Radecke), and remained active as a composer until about 1910 (see list of compositions below). But it was seeing an 1889 concert by the Berlin Philharmonic led by Hans von Bülow, he wrote, that “decided my future.

Photo: Year 1895. Bruno Walter (1876-1962) with other man in white cap [mounted photograph]. Dated on back [“Sylt 1895”]. Sylt, Germany.

Now I knew what I was meant for. No musical activity but that of an orchestral conductor could any longer be considered by me.” He made his conducting début at the Cologne Opera with Albert Lortzing’s Der Waffenschmied in 1894. Later that year he left for the Hamburg Opera to work as a chorus director. There he first met and worked with Gustav Mahler, whom he revered and with whose music he later became strongly identified.

Conducting and Gustav Mahler

In 1896, he was appointed Kapellmeister of the Stadttheater (municipal opera) in Breslau, on the strength of a recommendation from Mahler to the theater’s director, Theodor Löwe. However, Löwe required that before taking up this position the young conductor change his last name from Schlesinger, which literally means Silesian, “because of its frequent occurrence in the capital of Silesia”. In a letter to his brother paraphrased by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky, Walter said he had “suggested several names, which Mahler wrote down and gave to Löwe, who returned the contract with the name Bruno Walter.”

These biographers add that Walter wrote to his parents that he found that “having to change his name was ‘terrible,'”; they report that Mahler and his sisters “pressed” Walter to make the change of name, and add that, contrary to occasional unsubstantiated reports, it “is unknown” whether Löwe’s stipulation had anything to do with a desire to conceal Walter’s Jewish origins.

In 1897, Walter became Chief Conductor at the municipal opera in Pressburg (now Bratislava). He found the town provincial and depressing, and in 1898 took the position of Chief Conductor of the Riga Opera, Latvia. While there, he converted to Christianity, probably Roman Catholicism. In 1899 Walter was appointed music director of the Temeswar, Austria-Hungary (now Timisoara, Romania) Opera, the current Banatul Philharmonic of Timi?oara.

Photo: Year 1897. Bruno Walter (1876-1962) alone [Albert Meyer, Berlin]. With 2-line inscription, signature [“Bruno”], and date [“Wien den 22.IX.97”] on back. 22-09-1897.

Walter then returned in 1900 to Berlin, where he assumed the post of Royal Prussian Conductor at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, succeeding Franz Schalk; his colleagues there included Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Karl Muck (1859-1940). While in Berlin he also conducted the premiere of Der arme Heinrich by Hans Pfitzner (1869-1949), who became a lifelong friend.

In 1901, Walter accepted Mahler’s invitation to be his assistant at the Court Opera in Vienna. Walter led Verdi’s Aida at his debut. In 1907 he was elected by the Vienna Philharmonic to conduct its Nicolai Concert.

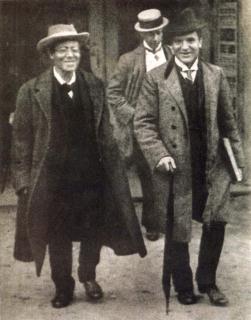

Year 1908, Prague. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Bruno Walter (1876-1962).

1908. Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major by Bruno Walter (1876-1962). Composed for Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) and dedicated to him: “Dem Lieben Freunde und grossen Künstler / Arnold Rosé / gewidmet”. Composition circa 1908. Premiered by Bruno Walter and Arnold Rose in Vienna in 09-03-1909 (Year 1909). First publication 1910. Copyist’s copy.

In 1910, he helped Mahler select and coach solo singers for the premiere of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8. In the following years Walter’s conducting reputation soared as he was invited to conduct across Europe – in Prague, in London where in 1910 he conducted Tristan und Isolde and Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers at Covent Garden, and in Rome.

When Mahler died on 18-05-1911, Bruno Walter was at his deathbed. On 06-06-1911, he wrote to his sister that he was to conduct the premiere of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde; he did so in Munich on 20-11-1911, in the first half of an all-Mahler concert (the second half contained Mahler’s Symphony No. 2). On 26-06-1912 he led the Vienna Philharmonic in the world premiere of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9.

06-06-1911: Letter from Bruno Walter (1876-1962) in Bad Gastein (Austria) to Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938): Walter tries to console both himself and Justine over the death of Mahler the previous 18-05-1911.

I would just like to tell you that my thoughts will be with you tomorrow as your sorrowful hearts will heave with new vehemence. It presses on me here also …. And I can always refresh myself with the hope to reduce at least some of my grief and sorrow in action: in the two premières of his works which I will give this coming winter. This will also be something for you, I hope. Tomorrow you are going with Elsa and Arnold to visit his grave-how gladly would I stand there too! Farewell! In faithful remembrance, I greet you and Arnold. Cordially yours, Bruno.

This concerns: Bruno Walters wife Elsa and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

06-06-1911: Letter from Bruno Walter (1876-1962) to Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938), signature Bruno (Walter).

Munich

Although Walter became an Austrian citizen in 1911, he left Vienna in 1913 to become the Royal Bavarian Music Director and General Music Director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. While there, argue Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky, “Walter’s contribution to the history of Wagner performance is more significant than many realize. The Bayreuth Festival was suspended after 1914… and resumed only in 1924. During those nine years, Munich was the centre of authentic Wagner performance; its Prinzregenttheather was closely patterned after the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, and its National Theatre had seen the world premieres of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, and Tristan und Isolde. Walter was the city’s music director for most of this period, and he presided over most of the Wagnerian repertoire.”

In January 1914 Walter conducted his first concert in Moscow. During the First World War he remained actively involved in conducting, giving premieres to Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violanta and Der Ring des Polykrates as well as Hans Pfitzner’s Palestrina. In 1920 he conducted the premiere of Walter Braunfels’ Die Vögel.

In Munich, Walter was a good friend of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII). Walter’s close friendship with Thomas Mann seems to have begun in Munich by 1914.

United States

Walter ended his Munich appointment in 1922 and left for New York in 1923, working with the New York Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall; he later conducted in Detroit, Minnesota and Boston.

Berlin, Leipzig, Vienna

Back in Europe, Walter made his debuts with both the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1923, and was Music Director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin (Städtische Oper) from 1925 to 1929. He made his debut at La Scala in 1926, and was chief conductor of the German seasons at Covent Garden in London from 1924 to 1931.

Walter served as Principal Conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra from 1929 until March, 1933, when his tenure was cut short by the new Nazi government, as detailed below.

In speeches in the late 1920s, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler had complained bitterly about the presence of Jewish conductors at the Berlin opera, and mentioned Walter a number of times, adding to Walter’s name the phrase, “alias Schlesinger.” When the Nazis took power, they undertook a systematic process of barring Jews from artistic life.

As reported by biographers Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky, when Hitler became chancellor in January, 1933, Walter was conducting in New York, but the next month sailed back to Leipzig planning to conduct his previously scheduled concerts with the Gewandhaus Orchestra in March. However, Leipzig’s Chief of Police informed management that he would cancel the concerts if Walter was to conduct them. Management resisted and Walter led rehearsals, but on the day that the first concert was to take place, the police, “in the name of the Saxon ministry of the interior,” forbade the dress rehearsal and the concerts; Walter left Leipzig.

Walter was then scheduled to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic on March 20, but its managements was warned by Joseph Goebbels that “unpleasant demonstrations” might occur at the concert, and the Propaganda Ministry clarified this by saying that there would be violence in the hall; hearing of this, Walter chose to withdraw, saying to management, “Then I have no further business here.” The concert, in the end, was conducted by Richard Strauss. Walter later wrote, “The composer of Ein Heldenleben [“A Hero’s Life”] actually declared himself ready to conduct in place of a forcibly removed colleague.” A concert Walter was scheduled to lead in Frankfurt was also cancelled. Walter left Germany and was not to conduct there again until after the war.

Austria became his main center of activity for the next several years. He and his family moved to Vienna, where he regularly conducted the Vienna Philharmonic (with whom he made a number of momentous recordings during this period) and at the Salzburg Festival, and in 1936 he accepted an offer to be Artistic Director of the Vienna State Opera; there, he occupied the same office that had once been Mahler’s. He was also appointed Permanent Guest Conductor of the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO) from 1934 to 1939, and made guest appearances such as in annual concerts with the New York Philharmonic from 1932 to 1936.

When the Third Reich annexed Austria – the Anschluss – in 1938, Walter was in the Netherlands conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra. His elder daughter Lotte was in Vienna at the time, and was arrested by the Nazis; Walter was able to use his influence to free her. He also used his influence to find safe quarters for his brother and sister in Scandinavia during the war.

1939. Arrival Bruno Walter (1876-1962) in Amsterdam: Willem Mengelberg (1871-1951), porter, Elsa Walter (1871-1945) and Bruno Walter (1876-1962).

Walter’s daughter Gretel was murdered on August 21 of 1939 in Berlin by her husband, who then killed himself; his motive was jealousy over her growing relationship with the Italian bass Ezio Pinza. Walter’s wife fell into a permanent depression and died in 1945, and Walter blamed himself for the tragedy, as his daughter had met Pinza only because Walter had made special efforts to hire him to sing the role of Don Giovanni.

Return to the United States

On November 1, 1939, he set sail for the United States, which became his permanent home. He settled in Beverly Hills, California, where his many expatriate neighbors included Thomas Mann.

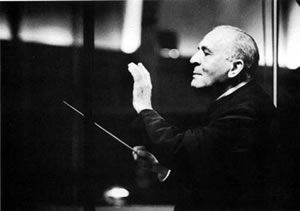

Los Angeles. Bruno Walter (1876-1962) with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (CSO).

While Walter had many influences within music, in his Of Music and Making (1957) he notes a profound influence from the philosopher Rudolf Steiner. He notes, “In old age I have had the good fortune to be initiated into the world of anthroposophy and during the past few years to make a profound study of the teachings of Rudolf Steiner.

Here we see alive and in operation that deliverance of which Friedrich Hölderlin speaks; its blessing has flowed over me, and so this book is the confession of belief in anthroposophy. There is no part of my inward life that has not had new light shed upon it, or been stimulated, by the lofty teachings of Rudolf Steiner … I am profoundly grateful for having been so boundlessly enriched … It is glorious to become a learner again at my time of life. I have a sense of the rejuvenation of my whole being which gives strength and renewal to my musicianship, even to my music-making.”

During his years in the United States, Walter worked with many famous American orchestras. In December, 1942, he was offered the music directorship of the New York Philharmonic, but declined, citing his age; then in February, 1947, after the resignation of Artur Rodzinski, he accepted the position but changed the title to “Music Adviser,” (he resigned in 1949). Among other orchestras he worked with were the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the NBC Symphony Orchestra, and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

From 1946 onwards, he made numerous trips back to Europe, becoming an important musical figure in the early years of the Edinburgh Festival and in Salzburg, Vienna and Munich. In September, 1950 he returned to Berlin for the first time since the aborted concert of 1933; he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in a program of Beethoven, Mozart, Richard Strauss, and Brahms, and “gave a lecture for the students of the Municipal Conservatory – formerly his old school, the Stern Conservatory – at the students’ request”

1947. 25-10-1947 Bruno Walter (1876-1962) and the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (RCO) in rehearsal in the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw.

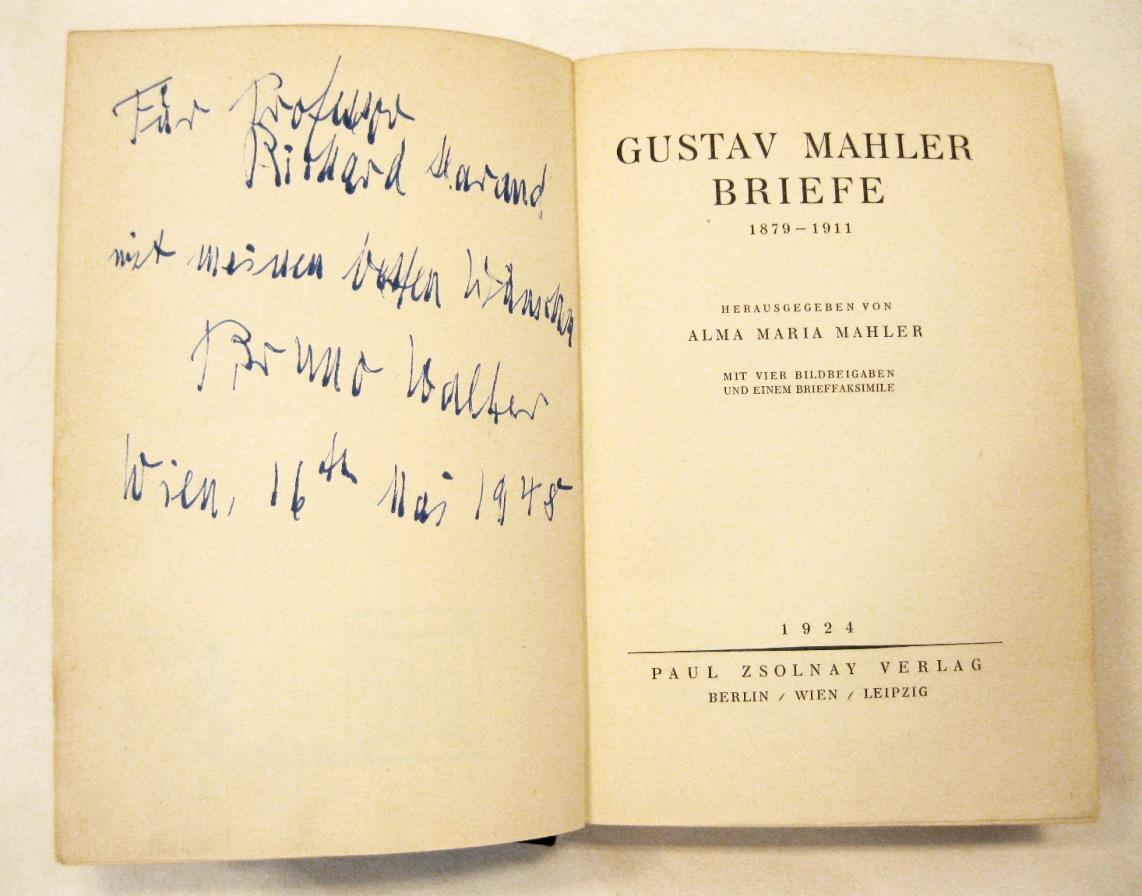

1948. Signature Bruno Walter (1876-1962) in book titled “Gustav Mahler Briefe” published by Paul Zsolnay (1895-1961) in 1924. Vienna, 16-05-1948. For Professor Richard Marand (?)

Bruno Walter (1876-1962), Thomas Mann (1875-1955) and Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957).

His late life was marked by stereo recordings with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble of professional musicians assembled by Columbia Records for recordings.

1952. Bruno Walter (1876-1962) and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (1915-2006) in the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw after a performance of Gustav Mahlers’ Symphony No. 4.

1959. 05-09-1959 Telegram Bruno Walter (1876-1962) in Beverly Hills to the Mayor of Steinbach am Attersee about a Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) plaque.

He made his last live concert appearance on December 4, 1960 with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and pianist Van Cliburn. His last recording was a series of Mozart overtures with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra at the end of March in 1961. Bruno Walter died of a heart attack in his Beverly Hills home in 1962. But he is buried in Abbondio Cemetery, Gentilino in Canton Ticino, Switzerland.

More

In 1894, when he was not yet 18, Bruno Schlesinger made his debut as a conductor, leading a performance of the light opera Waffenschmied by Albert Lortzing. The reviews were enthusiastic. A few days later, he conducted an emergency performance of the same work. The original cast was not available for this unscheduled performance. Two of the singers who were called in at the last minute hadn’t sung their roles in years. One of the reviews was quite hostile. Then another newspaper came to Schlesinger’s defense. Controversy may be an even better source of publicity than praise. At the age of 17, Schlesinger had achieved fame and success.

Who was this Bruno Schlesinger? The world knows him as Bruno Walter. In 1896, he was offered a job at the Breslau Stadttheater under the condition that he change his name. Perhaps the director of the Stadttheater thought the name Schlesinger sounded too Jewish. Bruno was not happy about changing his name, but he gave in to pressure; he has been Bruno Walter ever since then. Nevertheless, in 1921 the pro-Nazi critic Hermann Esser described him as “the Jew conductor Isidor Schlesinger, alias Walter.” Esser was being provocative about the name “Isidor”; perhaps he felt that someone who had changed his Jewish-sounding surname should be accused of changing a Jewish-sounding given name as well.

In addition to changing his name, which was a response to pressure, Bruno Walter changed his religion. It is not entirely clear which branch of Christianity he joined, but it was probably Catholicism, since his ashes were buried in a Catholic cemetery. His conversion seems to have been quite sincere. His daughter Lotte is cited as saying, “He was a Christian, and a very good one. And the older he got, the more religious he really became.”

A different musician, British composer Gerald Finzi, did not consider himself a Jew but never wanted to become a Christian or anything else. In 1938, Finzi tried to destroy evidence of his Jewish origins because he was afraid Hitler might win the war.1 Walter’s situation was just the opposite. He wanted to convert. Furthermore, unlike Finzi, Walter underestimated the danger of anti-Semitism. When Hitler took power, Walter was conducting at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, but he returned to Germany after the engagement. He thought, for a very short while, that he could still conduct in Germany, until a concert he was scheduled to conduct at the Leipzig Gewandhaus was canceled on the morning of the performance.

Walter then moved to Vienna. He courageously chose African-American contralto Marian Anderson as soloist in a performance of Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody to be given on June 17, 1936. He received a death threat, but the show went on. That same month, Austrian Nazis threw stink bombs during a performance of Tristan und Isolde conducted by Walter, but the show went on. When Hitler took over Austria in 1938, Walter once again was conducting abroad, in Amsterdam. This time, he knew enough not to return home. He eventually moved to America, where he was as successful and admired a conductor as he had been in Germany and Austria.

Walter was a contemporary of Arturo Toscanini, probably the world’s most admired conductor at the time. Toscanini was known for his accurate, precise interpretations and his generally fast tempos. Walter’s style was perhaps more varied and more romantic. Had there been no Toscanini, Walter might have been the most famous conductor on earth. Nevertheless, Walter and Toscanini, both of whom had to flee to America, were friends.

Toscanini never conducted the music of Gustav Mahler. Walter, on the other hand, considered Mahler, like Walter, a convert to Christianity–his mentor. Walter loved and understood Mahler’s music and conducted it often. Today, Mahler is much admired and frequently performed, but he was rather less popular during the first half of the 20th century. Walter was one of Mahler’s champions. Mahler appreciated Walter’s conducting; he did not, however, like Walter’s compositions. Neither did anyone else, apparently. Despite Walter’s unbroken success as a conductor, he was a total failure as a composer. Few people even know that he composed.

Walter’s personal life, despite his triumph as a conductor, was filled with disappointment and tragedy. The fact that his compositions are unknown was one source of sadness. Another was his love life. He remained married to his wife Elsa for almost 44 years until she died in 1945, but loved a different woman, the singer Delia Reinhardt. He was deeply grieved when he had to flee Germany and then Austria after Hitler took over. Worst of all, his younger daughter, Gretel, fell in love with baritone Ezio Pinza and was murdered by her jealous husband, a man named Robert Neppach, who then killed himself.

Walter was knowledgeable, literate and intellectual. He numbered Nobel-Prize-winning author Thomas Mann among his friends. At the same time, he believed in anthroposophy, a highly controversial, anti-materialist system of spirituality developed by Rudolf Steiner. It was Delia Reinhardt who introduced Walter to this belief, but his passion for it cannot be explained simply by his love for Reinhardt. He became ever more involved. He did not see a contradiction between his Christian belief and the fact that Steiner said Jesus “had been visited by the spirit that had once inhabited Moses and Zoroaster.” Nor did he see a conflict between Steiner’s mysticism and his own intellectuality. Walter did not even seem to be troubled by the contradiction between his own belief in “freedom of thought and of understanding and peace between the single persons and between the nations” and Steiner’s apparent view that “the black race belongs to the night, the yellow race to the morning, the whites to the day.”

Ryding and Pechefsky have written a detailed, well-documented biography of a respected musician whose career as a conductor was long and successful. There remains very much that they could not find. What on earth was Walter thinking when he embraced anthroposophy? Did he know what Steiner had written about race? Or did he find other passages in Steiner’s writings that made the racism sound harmless? And what about Walter’s feelings for Elsa, his wife? Did he love her and Delia Reinhardt at the same time? Or did he stay with Elsa because of a sense of duty? What did Walter think when he was described as “the Jew conductor Isidor Schlesinger”? What did he think when he had to flee Germany and then Austria? Did he identify as a Jew at that time? Or did he consider himself a Christian who was unjustly blamed for his ancestors?

Recordings

Walter’s work was documented on hundreds of recordings made between 1900 (when he was 24) and 1961. Most listeners became familiar with him through the stereo recordings made in his last few years, when his health was declining. But many critics agree that these recordings do not fully convey what Walter’s art must have sounded like in its prime. For one thing, the late recordings sometimes have a geniality that contrasts with the more mercurial, intense, and energetic performances Walter recorded in earlier decades. For another, the late recordings focus mostly on music from Mozart through Mahler, but in Walter’s youth he often conducted what was then newer music (including Mahler).

Walter worked closely with Mahler as an assistant and protégé. Mahler did not live to perform his Das Lied von der Erde or Symphony No. 9, but his widow, Alma Mahler, asked Walter to premiere both. Walter led the first performance of Das Lied in 1911 in Munich and of the Ninth in 1912 in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic. Decades later, Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic (with Mahler’s brother-in-law Arnold Rosé still a concertmaster) made the first recordings of Das Lied von der Erde in 1936 and of the Ninth Symphony in 1938. Both were recorded live in concert, the latter only two months before the Nazi Anschluss drove Walter (and Rosé) into exile.

These recordings are of special interest for the performance practices of the orchestra and also for intensity of expression. Walter was to re-record both works successfully in later decades. His famous Decca Das Lied von der Erde with Kathleen Ferrier, Julius Patzak, and the Vienna Philharmonic was made in May, 1952, and he recorded it again in studio with the New York Philharmonic in 1960. He conducted the New York Philharmonic in the 1957 stereo recording of the second symphony. He recorded the Ninth in stereo in 1961.

Since Mahler himself never conducted the Ninth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde, Walter’s performances cannot be taken as documentations of Mahler’s interpretations. But in the light of Walter’s personal connection with the composer, and his having given the original performances, they have another kind of primary authenticity. In his other (greatly esteemed) recordings of Mahler – various songs and the First, Second, Fourth, and Fifth symphonies – there is the great added interest that he had heard Mahler’s own performances of most of them.

Walter made many highly acclaimed recordings of other great Germanic composers, such as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Johannes Brahms, Johann Strauss Jr., and Anton Bruckner, as well as of Bach, Wagner, Schumann, Dvorak, Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Smetana, and others. Walter was a leading conductor of opera, particularly known for his Mozart, and recordings of some from the Metropolitan Opera and the Salzburg Festival are now available on CD. So are performances of Wagner, Verdi, and Beethoven’s Fidelio. Also of great interest are recordings from the 1950s of his rehearsals of Mozart, Mahler, and Brahms, which give insight into his musical priorities and into the warm and non-tyrannical manner (as contrasted with some of his colleagues) with which he related to orchestras.

Compositions

Walter composed actively until at least 1910. As detailed in the biography by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky, his compositions include:

- Symphony No. 1 in D minor (composed circa 1907; premiered in Vienna, 1909; recorded by CPO #777 163-2, 2008).

- Symphony No. 2 in E (composed circa 1910).

- Symphonic Fantasia (composed 1904; premiered by Richard Strauss in 1904).

- String Quartet in D major (1903; premiered in Vienna by the Rose Quartet).

- Piano Quintet (premiered in 1905 in Vienna by the Rose Quartet).

- Piano Trio (premiered in 1906 in Vienna by Walter and members of the Rose Quartet).

- Sonata for Violin and Piano in A (1908; composed for Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946), and dedicated to him: “Dem Lieben Freunde und grossen Künstler / Arnold Rosé / gewidmet”. Composition circa 1908. Premiered by Bruno Walter and Arnold Rose in Vienna in 09-03-1909. First publication 1910. The opening Allegro con espressione begins in a confident mood. However, as the movement progresses, we hear the rhythmic pounding of a fate motif which creates doubt and a sense of foreboding. The second movement, Andante serioso, though lyrical in part, retains a certain rhythmic angularity. The finale, Moderato, begins in the minor, marked calmo. However, it does not stay calm for long, either in mood or tonality as it eventually moves into the tonally warmer key of A Major. See titlepage on this webpage.

- Incidental music for “King Oedipus” (1910. The production was an adaptation of the Sophocles play by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. It was directed by Max Reinhardt, and premiered in September, 1910 in Munich, followed by performances in Berlin, Cologne, and Vienna.

- Numerous songs.

- Choral Works.

Written works

- Gustav Mahler’s III. Symphonie. In: Der Merker 1 (1909), 9–11.

- Mahlers Weg: ein Erinnerungsblatt. In: Der Merker 3 (1912), 166–171.

- Über Ethel Smyth: ein Brief von Bruno Walter. In: Der Merker 3 (1912), 897–898.

- Kunst und Öffentlichkeit. In: Süddeutsche Monatshefte (Oktober 1916), 95–110.

- Beethovens Missa solemnis. In: Münchner Neueste Nachrichten (30. Oct. 1920), Beethoven suppl., 3–5.

- Von den moralischen Kräften der Musik. Vienna 1935.

- Gustav Mahler. Wien 1936.

- Bruckner and Mahler. In: Chord and Discord 2/2 (1940), 3–12.

- Thema und Variationen – Erinnerungen und Gedanken. Stockholm 1947.

- Von der Musik und vom Musizieren. Frankfurt 1957.

- Mein Weg zur Anthroposophie. In: Das Goetheanum 52 (1961), 418–21.

- Briefe 1894–1962. Hg. L.W. Lindt, Frankfurt a.M. 1969.

Notable recordings

- 1935: Richard Wagner, Die Walküre (Act I), with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, feat. soloists Lotte Lehmann, Lauritz Melchior, Emanuel List, et al. (EMI Great Recordings of the Century, Naxos Historical).

- 1938: Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 9, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. (Dutton, EMI Great Artists of the Century, Naxos Historical).

- 1941: Ludwig van Beethoven, Fidelio, with the Metropolitan Opera, feat. soloists Kirsten Flagstad, Alexander Kipnis, Herbert Janssen, et al. (Naxos Historical).

- 1952: Gustav Mahler, Das Lied von der Erde, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, feat. soloists Kathleen Ferrier and Julius Patzak. (Decca Legends, Naxos Historical).

- 1956: The Birth of a Performance: Walter’s rehearsals and finished performance of Mozart’s “Linz” Symphony, with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. A then-rare instance of rehearsals of a performance being issued on a commercial recording. (Sony Masterworks).

- 1958–1961: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 4 and Symphony No. 6, with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (Sony Bruno Walter Edition).

- 1960: Johannes Brahms, Symphony No. 2 and Symphony No. 3, with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. (Sony Bruno Walter Edition).

Bibliography

- Dalin, David G. (2005). The Myth of Hitler’s Pope: Pope Pius XII And His Secret War Against Nazi Germany. Washington, DC: Regency Publishing. ISBN 9780895260345.

- Fischer, Jens Malte (2011). Gustav Mahler. Translated by Stewart Spencer. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300134445.

- Friedländer, Saul (1997). Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume 1: The Years of Persecution, 1933–39. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780753801420.

- Hemleben, Johannes (2000). Rudolf Steiner: an Illustrated Biography. Sophia Books.

- Holden, Raymond (2005). The Virtuoso Conductors: the Central European Tradition from Wagner to Karajan. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09326-1.

- Ross, Alex (2007). The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374249397.

- Ryding, Erik; Pechefsky, Rebecca (2001). Bruno Walter: a World Elsewhere. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08713-0.

- Walter, Bruno (1961). Of Music and Music-Making. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. OCLC 394450.

- Walter, Bruno; Galston, James A. (1946). Theme and Variations: an Autobiography. New York: A.A. Knopf. OCLC 564814.