- Profession: Soprano.

- Residences: Melbourne, London, Paris, Brussels, New York City.

- Relation to Mahler: Worked with Gustav Mahler.

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- 00-01-1900, Year 1900.

- Born: 19-05-1861 Richmond, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

- Died: 23-02-1931 Darlinghurst, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

- Buried: Lilydale Lawn Cemetery, Lilydale, Yarra Ranges Shire, Victoria, Australia.

- Opera.

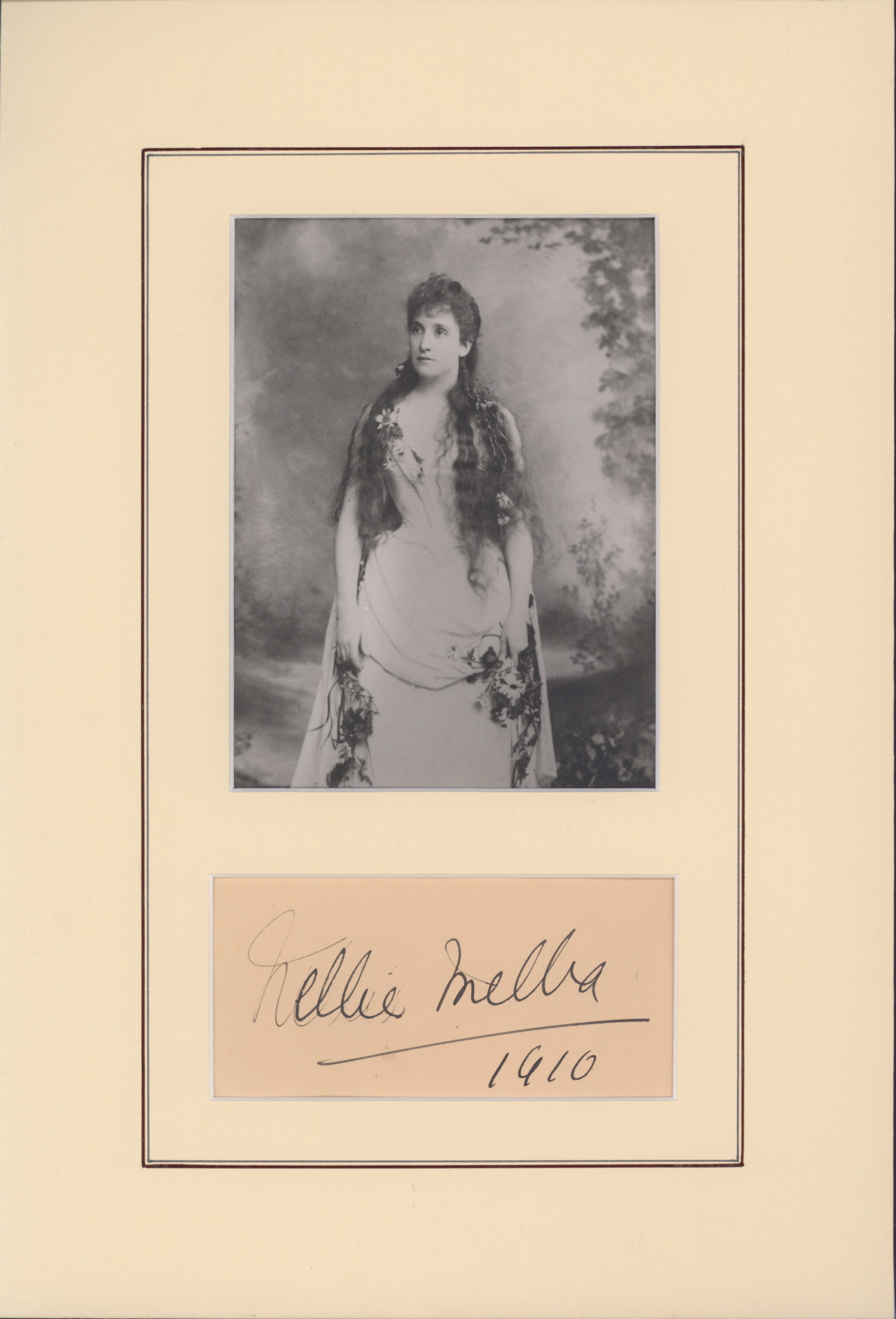

Dame Nellie Melba, born Helen “Nellie” Porter Mitchell, was an Australian operatic soprano. Helen Porter Mitchell, Nellie Armstrong, Helen Porter Armstrong. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early 20th century. She was the first Australian to achieve international recognition as a classical musician. She took the pseudonym “Melba” from Melbourne, her home town.

Melba studied singing in Melbourne and made a modest success in performances there. After a brief and unsuccessful marriage, she moved to Europe in search of a singing career. Failing to find engagements in London in 1886, she studied in Paris and soon made a great success there and in Brussels. Returning to London she quickly established herself as the leading lyric soprano at Covent Garden from 1888. She soon achieved further success in Paris and elsewhere in Europe, and later at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, debuting there in 1893. Her repertoire was small; in her whole career she sang no more than 25 roles and was closely identified with only ten. She was known for her performances in French and Italian opera, but sang little German opera.

During the First World War, Melba raised large sums for war charities. She returned to Australia frequently during the 20th century, singing in opera and concerts, and had a house built for her near Melbourne. She was active in the teaching of singing at the Melbourne Conservatorium. Melba continued to sing until the last months of her life and made a legendary number of “farewell” appearances. Her death, in Australia, was news across the English-speaking world, and her funeral was a major national event.

Dame Nellie Melba (1861-1931), prima donna, was born Helen Porter Mitchell on 19 May 1861 at Richmond, Melbourne, eldest surviving of ten children of David Mitchell, building contractor, and his wife Isabella Ann, née Dow. Her father’s business acumen and strict code of behaviour strongly influenced Melba, who later declared that of all the men she had known he had meant most to her. Her mother shared her husband’s taste for music and proficiently played a number of instruments including the family harmonium; she was the girl’s first music teacher. Nellie was not, however, an infant prodigy. Although she first sang in public when 6, forming a lifelong attachment to ‘Comin’ thro’ the Rye’, it was her humming that visitors noticed. Unwittingly she had hit upon what she would later describe as an effective vocal exercise. She also whistled, and generally behaved like a tomboy.

Educated first by her aunts, Melba was sent to a boarding school at Richmond before entering as a day-girl at the new Presbyterian Ladies’ College. There, in the context of the most advanced education then available to women in Victoria, she pursued her interests in singing and the piano: her teacher Mme Ellen Christian had been a student of the famous Manuel Garcia. Melba showed herself to be adept in elocution, accomplished at painting and in acquiring the social graces; in mathematics and English she was undistinguished.

Melba’s leaving school in 1880 was overshadowed by her mother’s death, followed by that of a sister. Deciding on a change of scene, David Mitchell contracted to buy a sugar mill near Mackay in Queensland. There the 21-year-old Nellie encountered Charles Nisbett Frederick Armstrong, tall, blue-eyed and three years her senior, a man who agreeably combined exceptional skills as a rough-rider with the recommendation of gentle birth: his father was a baronet. They were married in Brisbane on 22 December 1882. Sequestered in a tin-roofed house, Melba became bored with the incessant rain and frustrated by a foundering marriage. The birth of a son, George, did little to allay her growing ambition to sing professionally, and on 19 January 1884 she left Mackay for Melbourne.

Although Melba later repudiated her indebtedness to Pietro Cecchi, her then singing teacher, it was he who responded to her inquiring letter with an emboldening telegram, since he believed hers to be a voice which would enthral the world. Melba now applied herself totally, and on 17 May 1884 made her début at a Liedertafel concert at the Melbourne Town Hall. ‘She sings like one out of ten thousand’, wrote the Australasian’s critic. It was here she met John Lemmone, a flautist later to act as her accompanist, manager and opera company impresario, and who would be present at her deathbed.

After some success as a professional singer (she earned £750 in the first year) Melba accompanied her father, appointed Victoria’s commissioner to the Indian and Colonial Exhibition, to London in March 1886. At first she was captivated; but encouragement was not forthcoming. Sir Arthur Sullivan told her to keep on with her studies and in a year’s time he might offer her a small part in The Mikado; her one concert was smothered in fog and polite applause. However Melba had already arranged to have an audition in Paris with Mathilde Marchesi; a letter from Mme (Wiedermann-) Pinschof, wife of the Austro-Hungarian consul in Melbourne and herself a former pupil of Marchesi, introduced her. Marchesi immediately recognized her potential. Nevertheless it was necessary to refine Mrs Armstrong’s technique; the pupil’s voice may have been indebted to the teacher for its extraordinary durability, though not for a great deal else.

In the seven years he had taught her, Cecchi had placed the voice, coached her in the leading Italian operatic roles, and won her confidence to the point where she asked him to form a touring company. Mme Marchesi’s contribution was to send Melba forth to selected salons as much for her social education as for singing experience, and to introduce her to the various composers who visited the Ecole Marchesi. These included Delibes, Thomas, Massenet and in particular Gounod, who coached her in his operatic roles. The sense of indebtedness of ‘Melba’—Marchesi had pressed on her the necessity of taking a suitable name, so she chose a contraction of that of her native city—was enormous. Habitually she addressed her in correspondence as ‘Mother’, and repeatedly stated that Marchesi had been her only teacher. Certainly Marchesi had transformed the girl.

Melba made her début as an opera singer at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, on 13 October 1887. She was an immediate hit as Gilda in Rigoletto, a daughterly role for a 26-year-old; she went against custom and appeared in plaits. Subsequently she appeared in La Traviata and in Lucia di Lammermoor; then, on 24 May 1888, sang Lucia at Covent Garden. It was not a conspicuous success; although she later sang her favourite role of Gilda, she seemed to make little headway, and on being offered a secondary part by the management in another opera, packed her bags and returned to Brussels. However she had found an ally at Covent Garden in the influential Lady de Grey, who wrote begging her to return. Melba consented, but meanwhile made her Paris début as Ophélie in Hamlet on 8 May 1889. Acclaimed by press and public alike, she moved on to Covent Garden, where she appeared with Jean and Edouard de Reszke in Roméo et Juliette. ‘I date my success in London’, she later recalled, ‘quite distinctly from the great night of 15 June 1889’.

Melba was fortunate in that the greater part of her career coincided with Covent Garden’s golden age, even though its architect, the impresario (Sir) Augustus Harris, had initially engaged her reluctantly. Harris mounted spectacular productions involving hundreds, broadened the repertoire and widened the audience while still drawing the aristocracy; the Royal Opera’s extraordinary social status Melba found exhilarating. Even though some of her greatest triumphs occurred elsewhere, most notably at La Scala in 1893 and repeatedly in New York, it was to Covent Garden that Melba returned season after season, maintaining a permanent dressing room to which she alone held the key. There she reigned supreme: her eclipse by the ageing Patti in 1895 was temporary. A powerful figure behind the scenes, Melba effectively blocked a number of rivals. In 1913 Covent Garden commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of her first appearance there with a gala performance: Melba appeared as Mimi in La Bohème, a role she had studied with the composer and made famous.

Assisted materially by her friend Lady de Grey, Melba moved freely in high society. It was remarked that she carried herself as if to the manner born. On first-name terms with the great, she would sing at their houses only when it pleased her: a not unreasonable attitude when, in addition to her tours to Continental opera houses, she had been invited to sing in St Petersburg before Tsar Alexander III, had sung in Stockholm before King Oscar II, in Vienna before Emperor Franz Joseph, and in Berlin before Kaiser Wilhelm II; she had also been commanded by Queen Victoria to Windsor. ‘Years of almost monotonous brilliance’ was the summation on her Covent Garden farewell programme. When she appeared in distant places, she was mobbed (much as pop-singers are today). Meanwhile friendly advice from Alfred de Rothschild strengthened her financial position. Shortly after the turn of the century she bought a house in Great Cumberland Place, London, to be her home for more than twenty years, employing French workmen to remodel it in the style of Versailles.

Although Charles Armstrong had sailed with Melba to Europe, he joined the army to keep himself occupied and occasionally visited his wife and baby in Paris. He was reluctant to shed the marriage; a spectacular row on the occasion of Melba’s début in Brussels effectively ended it. In 1890 Melba met Philippe, Duke of Orleans, the dashing heir of the Bourbon pretender to the French throne, then living in England. The pair were glimpsed together in London, Paris, Brussels, St Petersburg, and Vienna where they indiscreetly shared a box at the Opera. The papers got hold of the story, and almost immediately Charles Armstrong filed a petition for divorce on the grounds of adultery. The case was eventually quietly dropped; diplomatic pressure may have been brought to bear. The scandal was enough to send the duke off on a two-year safari in Africa, and to impress upon a bereft Melba both the importance of discretion and an increased sense of solitariness. Armstrong, having spirited their son away to America, divorced her in Texas in 1900.

Melba’s circle increasingly included Australians and she kept effective contact with her family. In 1902 her long-awaited return home took place, for a concert tour to all States and New Zealand: from the concerts in Sydney and Melbourne alone she netted £21,000, the takings of one Sydney concert setting a new world record. Melba’s train journey was a royal progress southwards to Melbourne, where thousands turned out to greet her. A contingent from P.L.C. shrilled a ‘coo-ee’ as she alighted, while the Stock Exchange brokers waved their hats in the air as her carriage passed. For newly federated Australia, Melba represented glamour, success, and international acceptance: Melbourne in particular felt that she had made the place famous. Unfortunately, a week after she sailed for Europe in March 1903, John Ezra Norton penned an open letter in Truth which accused her of wilfulness, miserliness, parasitism and drunkenness. Norton made it plain that he would welcome a legal challenge and kept up the attack, but Melba, safely ensconced once more in London society, chose to ignore him. Unfounded stories of her fondness for the bottle continued to circulate for years afterwards.

Although she was entering her forties, Melba was at the peak of her career. She was commanded to sing for the president of France at Buckingham Palace; in 1904 she created the title role in Saint-Saëns’ opera, Helene, at Monte Carlo; and in 1906-07, since she was displeased with the Metropolitan, she deserted it for the recently founded, rival Manhattan Opera House, which she revived financially with a triumphant season. It was probably her finest hour. Shortly after that American tour she contracted pneumonia and, although she fulfilled her engagement at Covent Garden, found it necessary to go to Australia for a holiday. While she was away Luisa Tetrazzini, ten years younger, gave a season at Covent Garden and quickly became a sensation; however, once Melba returned she held her ground, even though on occasion she irksomely had to alternate roles. Tetrazzini’s success was even greater in America, where she settled; although no longer challenged, Melba had been made aware of the precarious nature of her primacy, and henceforth became increasingly concerned to develop her links with her homeland.

In 1909 she embarked on a ‘sentimental tour’ of Australia: she covered 10,000 miles (16,093 km), appearing in many remote towns. The further she toured, the deeper seemed the adulation: there were banquets, speeches, even small crowds at wayside stations as Melba progressed with an entourage consisting of her manager, a maid and a valet, together with two baby grand pianos. She would arrive a full twenty-four hours before a performance, and to sustain the excitement give her concert without an interval. On this visit she also began to promote what she regarded as the correct way of singing, essentially the Marchesi method as modified by herself. She bought a property at Coldstream near Lilydale, Victoria, and called in the architect and engineer John Grainger, father of Percy, to build Coombe Cottage. Increasingly it became the centre of her operations; nearly half of her remaining years would be spent in Australia. She returned in 1911 to head the celebrated Melba-Williamson Opera Company; Williamson’s arranged the venues, Lemmone and she engaged the artists. In England once more, she continued to command an extraordinary following: no fewer than seven kings and queens attended one gala performance at Covent Garden in 1914.

When World War I broke out, Melba had recently arrived at Coombe Cottage. To go back to Europe was difficult, but she did make three wartime concert tours of North America where she excited pro-allied sentiment, and also applied herself to raising funds for war charities at home, most notably by her spirited auctioneering of flags at the conclusion of her concerts. She probably raised as much as £100,000 for the war effort, and on one memorable occasion stated that she would be prepared, if necessary, to work on the wharves. When in 1915 two Austrian teachers (one of them Mme (Wiedermann-)Pinschof) resigned from the Albert Street Conservatorium to follow George Marshall-Hall back to the University of Melbourne, Melba’s response to what she saw as enemy action was to offer Fritz Hart her full support. Her connexion with the university, where she had laid the foundation stone of Melba Hall in 1913, was snapped; that with Albert Street thereafter grew to the point where today it is known as the Melba Memorial Conservatorium. Her interpretation classes there became famous, and drew students from all over the country; a martinet, she would pace up and down in her high leather boots, ably drawing out general points from students’ mistakes as they sang before her. To be taken up by Melba held terrors of its own. Stella Power, winner of a scholarship to Albert Street, was badgered beyond her temperamental capabilities since the diva was intent on establishing her as the ‘Little Melba’. Eager to create a school of bel canto in Australia, Melba provided her services gratis to Albert Street and made the conservatorium responsible for publishing her singing tutor, the Melba Method (1926).

The war over, Melba went to London to reopen Covent Garden; the city’s weariness and shabbiness depressed her deeply. But the brown tweed coats she noted disapprovingly in the stalls, in place of the formal attire and tiaras of pre-war ‘Melba nights’, were but an indication of changed social conditions and the declining status of Covent Garden. She did not appear there again until 1923; in Australia she sang, offering cheap tickets, at the immensely successful Concerts for the People in Melbourne and Sydney in 1922, which drew some 70,000 people. A further Melba-Williamson opera tour took place in 1924; here she did her best to upstage the young Toti dal Monte. Beverley Nichols, who travelled with her while ghost-writing her Melodies and Memories (1925), later writing the novel Evensong (1932) about her, observed the ‘unutterable weariness of the perpetual struggle to keep her supremacy when her voice and her body were growing old’. Melba returned to England and on 8 June 1926 gave her farewell performance at Covent Garden. Three Australians sang with her in three of her best-known roles: one of them (at her insistence) was John Brownlee, making his Covent Garden début.

Melba now began a series of farewell appearances that, in ‘doing a Melba’, was to enrich the language as well as bolster her self-esteem. As early as October 1924 she had announced her Australian farewell to grand opera, but her last operatic performances, again in a portmanteau programme, occurred at the end of the third Williamson-Melba season (as the order had now become) in Sydney on 7 August and in Melbourne on 27 September 1928. Two months later in Geelong she gave her last Australian concert. Feeling that she had been away too long, Melba left for Europe for two years, and sang in Brighton before moving on to Paris and Egypt, where she developed a fever. She never quite shook it off; however she managed to sing one last time at a charity entertainment at the Hyde Park Hotel, London. Dreading another northern winter, Melba decided to return to Melbourne, but her health grew worse on board ship. Partly in the hope of getting better medical care, she later went to Sydney where, in St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, she died on 23 February 1931 of septicaemia, which had developed from facial surgery in Europe some weeks before.

Though tempered with some astonishment that so great a personage should have been a singer, the obituaries read as though for the passing of a monarch. ‘Is it too much to say’, asked the Argus, ‘that she was the greatest Australian?’; in Canberra parliamentarians stood with heads bowed to honour her memory. As a visiting English musician had earlier written, it was difficult for anyone outside the country to realize the extraordinarily powerful position Melba occupied in Australia. She may indeed have told Dame Clara Butt to ‘Sing ’em muck!’; certainly Melba felt obliged to pronounce on everything from the state of the Empire to the condition of the road to Portsea. In England she would trade on her Australianness to be brash and forthright, but in Australia, Beverley Nichols recalled, travelling with Melba ‘was like travelling through France with Marie-Antoinette’. She would bestow graded, lavish tiepins as if they were decorations, certificates of approval to shopkeepers, and for her students at Albert Street designed a uniform complete with a blue letter ‘M’. There were many acts of public charity and private generosity. Convinced of her own importance, she believed that the accidents which occurred during an American tour during World War I were German-inspired attempts to eliminate her, so effective had she been in the war effort. Her autobiography shows that Melba’s social successes were quite as important to her as her singing ones. Yet, as she once remarked to an inquiring aristocrat, ‘there are lots of duchesses but only one Melba’.

A splendid constitution and tenacity of purpose, allied with exceptional powers of concentration and attention to detail, were elements of a charismatic personality which enabled Melba to remain for so long in the forefront of the musical world. Her sense of theatre comprehended the audience as well as the piece in hand; on one occasion her direct intervention from the stage prevented a panic when fire broke out, and in a production of The Barber of Seville in San Francisco in 1898, the year of the Spanish-American war, she won the hearts of a restless audience by singing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ in the music-lesson scene. Ruthless to rivals, she was quite capable of singing the same part from the wings in order to undermine a singer she did not like. A practical woman, she knew how to drive a hard bargain, while her feeling for show-biz gave her sureness of touch in dealing with the press.

Melba believed that her voice and personality were of a kind that came together only once a century. Certainly she drew the admiration of other singers, and even had the capacity to make them sing better. But not everyone rated her so highly. Whatever the case in London and New York, and to a lesser degree the Francophone countries, her standing was not quite so high beyond: Sir Thomas Beecham believed this to be because she was ‘wanting in genuine spiritual refinement’, while others spoke of her coldness. George Bernard Shaw, then a music critic, initially found Melba ‘hard, shallow, self-sufficient and altogether unsympathetic’, but by 1892—after the break with the duke of Orleans—he acknowledged her as not merely a brilliant singer but a dramatic soprano. Shortly afterwards Melba’s limitations were made painfully apparent: her Brunnhilde in Siegfried at the Metropolitan in 1896 was a disaster, and her singing of the title role in Aida a few years later was scarcely more successful. Similarly, although Melba claimed that Puccini wrote the part of Madame Butterfly for her, and she studied it with him, something in the role eluded her and she never sang it.

She was at her best either in those parts which required a light voice, such as Gilda, Lucia, or Marguerite, or which did not require too great an exploration of psychological complexities, such as the lusty Nedda or the pathetic Mimi. In these parts she was so popular that her repertoire shrank to a dozen roles: she learned no new parts after 1904. She only twice created roles, both in undistinguished works; only after World War I did she put her aptitude for languages to use by singing chansons. The fact remains, however, that she sang with seeming effortlessness, producing a voice which Sarah Bernhardt described as being ‘pure crystal’, and which the soprano Mary Garden admired for the way it left the stage and seemed to hover in the auditorium like a beam of light. For Percy Grainger, ‘Her voice always made me mindsee Australia’s landscapes’.

It was as ‘the Voice’ that Melba sometimes chose to describe herself. ‘Good singing’, she stated, ‘is easy singing’; nature had given her an almost perfect larynx and vocal cords. Her range was fully three octaves, while her registers were so well blended that even an eminent throat specialist thought they were one. A scientific measurement of her trill produced twenty feet of undulations between perfectly parallel lines. Instrumentalists admired her, not least for the way that, despite her imperious temperament, she scrupulously sought to realize the composer’s intentions. From 1904 Melba began recording; she issued over one hundred records and helped to establish the gramophone. In 1920 she also became the first artist of international standing to participate in direct radio broadcasts.

Melba was appointed D.B.E. in 1918, and G.B.E. in 1927. She was survived by her son, and left an estate valued at £67,511: in 1914 she had been worth much more. Among her bequests was £8000 to the Albert Street Conservatorium for a singing scholarship, ‘in the hope that another Melba may arise’. Of the portraits painted, those by Rupert Bunny and John Longstaff are the best known; both are in the National Gallery of Victoria. Neither depicts the young Melba, with the electricity of her auburn hair and lively eyes, her majestic profile and frank mouth; nor do they show the Melba of later years, the one familiar to millions of Australians reading their newspapers, a cultural icon swaddled in furs and splendid isolation.