- Profession: Short-story writer, publicist, translator.

- Residences: Munich (House Janko Cadra), Bisonne (House Janko Cadra).

- Relation to Mahler: Friend. He kept diaries of his meetings with Gustav Mahler. Attended 1910 Concert Munich 12-09-1910 – Symphony No. 8 (Premiere).

- Correspondence with Mahler: Yes.

- Born: 06-12-1882 Myjava, Slovakia (at that time Upper Hungary).

- Died: 07-10-1927 Bissone, Switzerland. House Janko Cadra.

- Buried: Myjava, Slovakia.

The Archives of the Slovak Literary Institute in Martin have been assembling an extensive written heritage of writer and translator Ján Cádra (Janco). Of all the documents it is a set of Cádra´s diaries that draws most attention. He started writing them in September 1904 at the request of William Ritter (1867-1955).

Cádra finished studies at the Academy of Commerce in Prague, nevertheless he preferred writing and publishing articles and stories for various magazines and newspapers, wrote travel sketches, reviewed new books, etc. He also translated some works of Czech and Slovak literature into French and gained recognition for publishing Czech and Slovak novels and stories in France and Switzerland.

Janko Cádra got acquainted with William Ritter (1867-1955) in 1903 and became his friend, confidante and his secretary. He negotiated Czech and Slovak matter for Ritter. Being his companion, Cádra had a splendid opportunity to meet outstanding personalities including Gustav Mahler.

Besides diaries about Gustav Mahler he wrote articles about:

- 1910 Concert Munich 12-09-1910 – Symphony No. 8 (Premiere),

- 1912 Concert Vienna 26-06-1912 – Symphony No. 9 (Premiere, posthumous) (with William Ritter (1867-1955)).

In the diaries he described probably all his meetings with Mahler as well as his own reflections of Mahler’s music. There are many records of Cádra´s in the Archives of the Slovak Literary Institute. This article is about a small part. Cádra was interested in both Mahler, the composer and Mahler, the man.

Comparing William Ritter (1867-1955) and Janko Cadra (1882-1927)‘s records a certain similarity in details is confirming correctness and reliability of both Ritter´s and Cádra´s diaries.

Diary records of the Slovak writer Janko Cadra (1882-1927) about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Year 1904: 25-02-1904 (not in the diary)

- Matice slovenska (Slovak Foundation in Martin): 55 S 27 – diary 01-11-1905 to 19-11-1906.

- William Ritter (1867-1955) was fascinated with Mahler’s music, though initially he opposed it; he converted in the course of the composer’s Prague performance of the Third Symphony on 25-02-1904 in the Neues Deutsches Theater (1904 Concert Prague 25-02-1904 – Symphony No. 3). If Ritter had belonged to the opponents of Mahler’s music, he found the same feelings of discomfort in his friend, Janko Cadra (1882-1927).

Year 1905: 02-03-1905

- For the first time Gustav Mahler was mentioned in Cádra´s diaries on 02-03-1905, when both friends visited Prague:

We were about to go to a chamber music concert, but, instead, we chose Mahler’s Fifth Symphony performed in the Neues Deutsches Theater. I was very angry that someone had such an audacity to play something like that. But on the other hand, Wilko (William Ritter) liked the symphony very much.

- Performance Symphony No. 5 in Prague. Conductor: Leo Blech (1871-1958).

- There are two other brief notes about Mahler on the opening pages of Cádra´s diaries:

Year 1905: 05-03-1905

5th March. (…) We slowly walked through Elis Avenue and the Bridge talking of music, of Mahler (I said I did not want to listen to his music any more). (…)

Year 1905: 07-03-1905

- And two days later, 7th March, Cádra wrote a brief note:

Today Wilko has continued in his work about Mahler that he had started on Friday and before lunch he was very satisfied with his work. (…)

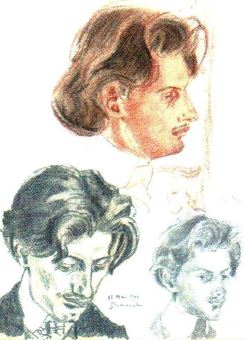

Year 1905. Janko Cadra (1882-1927) drawings by his friend William Ritter (1867-1955).

Year 1906: 07-11-1906

- Records of 7th and 8th November 1906 refer to Mahler’s Sixth Symphony performed in Munich in the Kaimsaal. In the course of the concert William Ritter met Gustav Mahler personally for the first time. Cádra´s descriptions of Ritter’s spontaneous reaction to the meeting with Mahler and of rehearsals belong to the most precious records. 1906 Concert Munich 08-11-1906 – Symphony No. 6.

(In the morning) I met Wilko leaning over the cooker mixing milk and cocoa. When I shortly told him I have read an announcement on a poster that on 8th November of this year a great concert would be given, he stopped mixing, straightened up and: ´- oh, quelle chance, quelle chance, quelle chance, … bravo,´ his eyes sparkled and he asked: ´… et quand?´

´Le 8 Novembre, …nous irons, n´est – ce pas?…´ I added with a smile. He turned to me, with a smile, too, saying nothing. (…)

Year 1906: 08-11-1906

Wilko was completely crazy about Mahler’s arrival, he did not talk about anything else and in every letter to the one or the other he kept making comments that Mahler would come. Well, he came on a Tuesday and the three of us: Wilko, Marcel (Marcel Montandon, a French music critic) and me, went to Kaimsaal to the first rehearsal. Marcel caught Mahler at the door, introduced himself, and Wilko and me introduced ourselves, too.

A little man of a mean stature, rather thin then slim, with a big head and standing out jawbones. After a whole night’s journey his face was yellow like wax; he still twitched his legs as if he was cold; after meeting Wilko, Mahler looked at him strangely but lovely as though he said to himself: ´Ah, so this is the Ritter…´- and he strongly shook his hands. They exchanged several words and Mahler entered the hall because many people were waiting for him there. With a score we went upstairs to the gallery. (…)

Wilko, Marcel and I were fascinated even by today´s imperfect performance and after a quick lunch we were again in the Kaimsaal. Mahler rehearsed the 1st, 3rd and 4th parts. When Alpine bells, which were operated behind the door under the organ by Mr. Pringsheim, rang, Mahler still asked, if they were heard and according to answers he ordered opening or shutting the door down or reducing the sound of the bells. Mahler said that at his spot they were heard well, but they must have been indispensably clear also in the audience! (…)

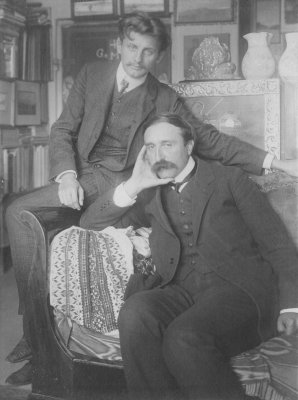

Year 1907. Janko Cadra (1882-1927) and William Ritter (1867-1955) in their Munich apartment.

Year 1908: 23-09-1908

- Two years later, on 19th September 1908 Gustav Mahler conducted the first performance of his Seventh Symphony (1908 Concert Prague 19-09-1908 – Symphony No. 7 (Premiere). Ritter and Cádra attended its Prague premiere. It is a great pity Cádra kept writing his notes about the Prague performance until a little later and for that reason they are not more comprehensive…

- 55 S 30 – diary 19-03-1908 to 03-11-1908.

(…) When we came to the concert hall, a big yellow building as if coated with mud, we strolled there since about half past nine. On occasions we entered, viewed a vaulted, hall as if decorated in an „Indian“ style, where chairs were placed for an evening concert, and then we walked outside back in again. Musicians were coming individually, both on a platform and outside they formed little groups; some of them played their music parts and everything around slowly came to life.

Several minutes after ten Wilko finally saw Mahler entering through a side door. We raced to him. He wore a grey-white overcoat and a hat of the same color. When he caught sight of us, he cried out: „Ah – „ and moved forward to us holding out his hand. Mr. Zemánek and another man (…) were with him. We introduced ourselves. After a short talk with Wilko Mahler climbed up the platform and the rehearsal began in a while. The 2nd, 3rd and 4th parts were on. Scarcely an orchestra started playing, Mahler stopped immediatelly and explained; and thus he continued up to the end of the rehearsal. (…)

Year 1908: 24-09-1908

(…) In any way I cannot recall Mahler’s VIIth! I have detailed notes, but I do not any longer remember musical passages that refer to it. It is better to listen to it and take some notes afterwards. An image sticks better. So for example I am only sure that scherzo is the most mahlerian part of the opus. The person who would not hear anything different from Mahler, would form the best image of him. Mahler is complete in scherzo.

When you listen to it, you both hate him and caress, curse and bless him. The orchestra seems to be running forward to the beautiful aim, the listeners join in, and suddenly – stop!, the orchestra breaks, alien tones halt all things and you send the author to hell. Incidentally we are not far from devilry. The whole scherzo reeks with hell. (…) I could not help smiling, when I had an impression that a little Slovak devil flashed by there.There is no denying that in Mahler’s work there are also Slovak melodies, of course only by their spirit, not by their forms. Especially in the scherzo and in the finale. The author himself may not know, how they got there – and it is better in this way – but my veinlets make obvious that they are there. (…)

Year 1908: 31-10-1908

- Several weeks later, on 27th October, Ritter and Cádra had an opportunity to attend another performance of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony in Munich. 1908 Concert Munich 27-10-1908 – Symphony No. 7. And Janko recorded such details:

(…) We sat at a round table beside the column to the right of the entrance. No sooner the first note struck, Mahler stopped the orchestra (…); He spoke quickly and indistinctly, we understood only a little of his talk, though we sat behind him. When he saw the orchestra was worried with a trifle for a long time, he started to talk about Mozart and thus he granted them a rest. (…) And having spoken the concluding words, (…) he raised both arms with words: „Also, meine Herrn…!“ and the rehearsal went on.

(…) Continually he corrected musicians. He knocked at the music stand with the baton and most of the orchestra stopped playing immediately. We could see a difference in comparison with the Czech Philharmony, where Mahler nearly wore out asking either to halt the play or calming musicians down. There is a big discipline here, no creaking, no walking up and down. – When a passage failed, when the orchestra did not understand, Mahler scratched nervously with the left hand in his hair, and stamped his feet till everybody stopped playing. Yet, when all musicians did not stop, he bent down to the score as a rabbit avoiding a bullet, almost touching the particular place with his nose and beating his baton against to the score, he thought about a reparation at the same time; and when the orchestra became silent at last, he quickly folded his hands between his knees remaining in his thoughts over the score for another while yet, suddenly he straightened up, said what he wanted and spread his arms to a new beginning. (…)

When the musicians were not able to understand for a long time, he got angry with them, rocketed like a bullet out off his chair stamping his feet and shouting: „Donnerwetter!“, but he immediately calmed again though wrath was perceptible in his voice. He explained with a suggestion of bitterness what was necessary to play and finished spreading his arms to conduct: „Also, meine Herrn!“

Once again it seemed to me as if the instrumentalist, who was not able to comprehend and play as Mahler wished, wanted to slip away; in this case Mahler straightened up in his chair, had a look at that side and beated to the music stand with his baton: “Ja, was ist denn das … Sie!“ An evasive answer. “Ja, mein Gott, Sie müssen doch spielen!…”

In his voice there is not any degradation. He is always firm, self-confident, but at the same time he is not challenging and above all he is not arrogant. His conviction, inner strength and honesty result from each word and each gesture. He does not forgive any difference between piano and pianissimo and nevertheless when he finally says: “Sind die Herrn müde?”, he can hear: “Nein.” “Sonst ich will Sie nicht anstrengen”. There is not any subservience, demanding appreciation and confessing humanity, however it is honest, straight manifestation of the thought that suddenly welled out of his heart, when he sees that some members of the orchestra are tired. (…)

Year 1910: 12-09-1910

- On 1910 Concert Munich 12-09-1910 – Symphony No. 8 (Premiere) Gustav Mahler performed his Eighth Symphony for the first time, the premiere was in Munich. For William Ritter and Janko Cádra, who lived in this city (House Janko Cadra), it was simple to attend this performance. The Eighth Symphony is one of Mahler’s greatest; up to our days it is always an important event.

- 55 S 36 – diary 04-07-1910 to 24-01-1911.

(…) On Tuesday, a rehearsal with children took part in the old town hall, where Mahler conducted with a cooking spoon… A concierge must have brought it to him.

(…) At the rehearsal, there were also the teachers of the children. As usual, Mahler was nervous, stamped his feet, threatened, quitted down, but nevertheless, he never was as angry as if he had rehearsed with the orchestra or with „the old“ choir. And as usual, after his outburst, he bantered and made the children laugh. There was a funny sight on his cooking spoon that he held by its wide end. (…)

He had a bad pianist; not only did he playoff time, but he left out notes, made mistakes as if he had stage fright. In the end, Mahler told him to play only the melody and not to mind the accompaniment, because the children depended only on the melody. To encourage them he put four or five trumpeters between them and they played as though they were to carry the whole choir. (…)

By the verse „Er wird uns lehren…“ Mahler told the children that they had to sing clearly and audibly enough so that all the parents might identify each of them. (…)

At the end Mahler exchanged some words with Wilko. He was not very pleased, not in the least with the pianist, but what to do, they said he was the best of all for the time being. Then the children came rushing up and surrounded Mahler, he caressed them, made jokes, and slowly went out. (…)

Year 1910: 13-09-1910

(…) Last night Mahler’s success was really enormous, though the performance was not as successful as the rehearsals, however, the audience could not compare. After the first part – it took 24 minutes – there was a quite decent applause and after a 7 minute break the second part began with that mysterious world imagery and took 54 minutes. When last chords faded, the hall thundered, the children and singers waved with music papers… The applause took a quarter of an hour and Mahler had to appear to the audience 10 or 12 times. (…)

During rehearsals, Mahler amends the score up until the final moments and completes it. (…) … the changes never are different than changing forte to mezzo-forte or piano or vice versa, here and there crescendo and accentuation or adding the delicate instrument, chimes or keyboards, and so on, that entered his head at the last moment. But he never changed notes!

Year 1910: 14-09-1910

Yesterday, Mahler lived through another triumph. Indeed I have never seen one like this. I am not sure, how many times he had to return on the podium, certainly fifteen or twenty times, but the applause, banging and calling him outlasted about three-quarters of an hour till they switched off the lights. After the first part ended, the applause did not last for a long time. But real intelligence and emotion were felt in the whole hall. At the end Mahler returned to take a bow on his podium, no muscle moved in his face, his eyes vividly roved, every now and then he smiled to his acquaintances, waved his hand and vanished behind the organ again.

The most touching moment occurred when three girls brought him a big wreath with a red ribbon. They came from behind the podium wanting to put the wreath on Mahler’s head. He caught it but, because he stood on the edge of the podium, he staggered and nearly fell over, which caused certain merriment. Then he tore a twig, kissed it, and like an automatic machine came to thank to the audience and stood there for a little while. Then he approached the children and ladies, pulled a twig out from a button-hole, and waved to the children. They waved with music papers and shouted as if they wanted to stop him.

At a new calling out, Mahler went straightly to the children stretching his arms. Immediately as though hundreds of arms surrounded him, the children gathered stretching out their arms like gooses´ necks, and shouted awfully, just to have been able to touch him. Mahler waved to them that he would come to all of them and really he went along railings accompanied with a merry shout and whoops of joy. (…) To tell the truth, the children were like drunken and Mahler was deeply moved.

Year 1910: 13-10-1910

It seems that in the first part of the VIIIth symphony Mahler wanted to point out an idea of mankind asking for a blessing to live, and in the second part he pointed at mankind working honestly and being redempted by love. (…)

Both texts were the most suitable for him. Because he had the texts like Veni Creator Spiritus sung by the crowd as if he intended to choose the best from the best and in this way spread faith and love. (…)

Mahler is poet of love, faith, work and eternal salvation. (…)

Gustav Mahler legacy: 00-10-1911

- After Mahler’s death Ján Cádra returned in his memories to the first meeting with the composer’s music. In his inheritance there is an article written in October 1911, probably for the Czech National Journal (Národní listy):

Six years ago my friend took me to the concert of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony performed at the Prague German Theatre (02-03-1905). His works were only rarely on the programme, so we skipped an interesting concert with Czech repertoir which we booked for. Immediately after Mahler’s Symphony we left the theatre and I nearly leapt at my joyful friend.

“It is scandalous to take me to a beastly thing like that, the chap does not know, what music exactly is, he sneers his audiences, and you clap him in addition! He’s a clown, nothing is sacred to him, he is laughing at your naivety, the softest feelings of yours, he is sneering, he doesn’t know how to compose, he doesn’t know what a symphony looks like…”

My friend couldn´t help laughing, saying I blustered so much; in the end, still laughing, he declared: „Bravo, bravo, I like you, on and on, two years later you will adore Mahler! You cry, my boy, just like I did, but wait a bit, listen to this symphony twice or thrice else.“ Never, it has spoiled my evening, for its sake I omitted Vít?zslav Novák, certainly I won´t be sleeping, and to throw money down the drain for such a beastly thing once again?

I was like a madman and my contempt of Mahler grew up not only with my friend’s enthusiasm…

All through the year I observed each rehearsal of the Sixth in Munich – and he won me over. My friend was silent, but his eyes shone with a blissful flame. (…)

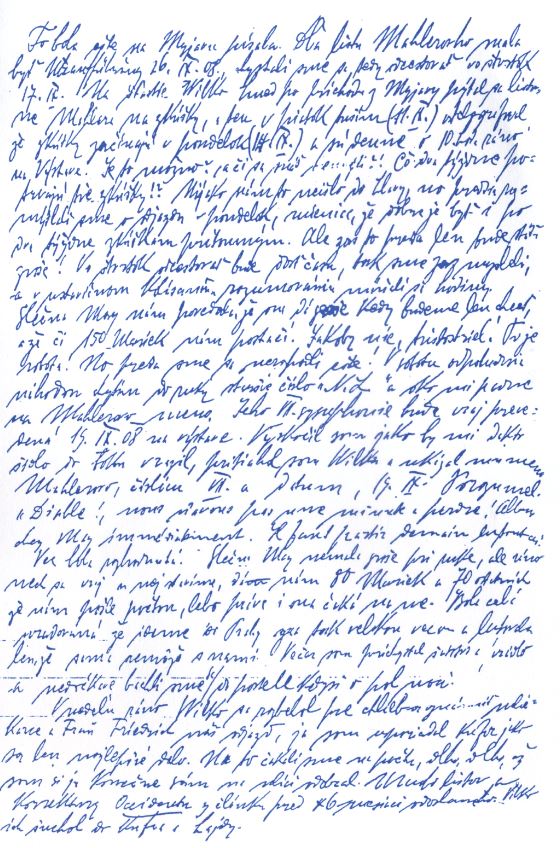

Janko Cadra (1882-1927) Mahler diary page about Symphony No. 7.

Janko Cadra published articles in several magazines and was very close to Le Corbusier. He translated the autobiography of Elena Marothy-Soltesova (1855-1939) called ‘Mes enfants du berceau a la tombe’ (‘From cradle to grave’) from Slovak to French. Published in 1928.

Editor: Milan Palak.