- Chronology: Year 1908

- Location: New York Metropolitan Opera (MET)

- Program: Fidelio

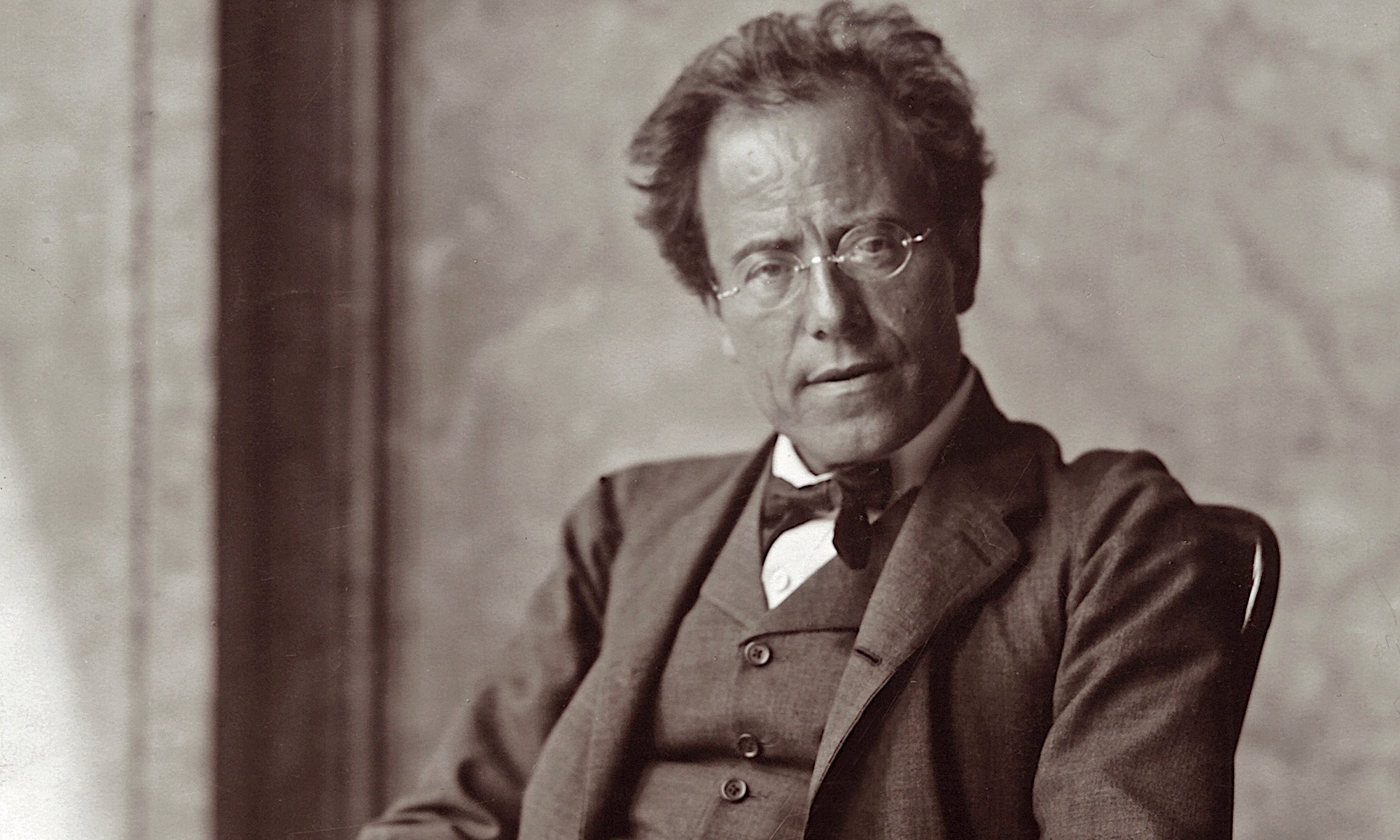

- Conductor: Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

- Orchestra: New York Metropolitan Opera (MET) Orchestra

- Singers: Berta Morena (1878-1952), Karl Burrian (1870-1924), Otto Goritz (1873-1929), Robert Blass (1867-1930), Bella Alten (1877-1962), Albert Reiss (1870-1940), Anton van Rooy (1870-1932)

- Stage design: Alfred Roller (1864-1935) (debut), Anton Brioschi (1855-1920) (debut)

- Notes: New York Metropolitan Opera (MET) repertoire Gustav Mahler, met036

Review of W.J. Henderson in the New York Sun:

“Many attempts have been made to give Beethoven’s opera ‘Fidelio’ an air of vital similtude, but in so far as the Metropolitan Opera House records go none more honest than that of last night can be recalled. The stage settings were a reproduction of those exhibited at Mr. Mahler’s opera house, the Imperial Opera of Vienna. It was in this style that Mr. Mahler succeeded in giving to the eyes of Vienna a picture of ‘Fidelio’ not to be forgotten. It was a credit to Mr. Conried that he was willing to give such a reproduction of it in the final days of his direction.

Mr. Mahler’s conception of the moods of the drama, which governed and characterized the entire performance, was one of the profoundest sympathy. In his treatment of the score he showed that keen perception of relative tonal values, of significant instrumental phrases, of general color, and of the proportions between orchestra and voices which was a repetition of that which he displayed in his production of ‘Don Giovanni.’ It was filled, where necessary, with a breathless intensity, and the dynamic climaxes, few and eloquent, were most potently arranged. Mme. Morena was in accord with Mr. Mahler’s ideas, and was consistent.

The chief credit for last night’s performance must go to the musical director. ‘Fidelio’ and ‘Don Giovanni’ have been his best achievements.”

Review of Richard Aldrich in The New York Times:

Beethoven’s “Fidelio” was produced at the Metropolitan Opera. House least evening for the first time in more than three years-and for the first time in many more years than that, if by “production” is meant an adequate well-considered and thoroughly prepared treatment of the great master’s only opera. It has in late years been hurriedly pitched upon the stage for a performance or so in a season, and to recall a proper interpretation of “Fidelio” it is necessary to think back to the days of the German opera at the Metropolitan under Seidl’s direction.

It is not the least of the titles that Gustav Mahler has to the respect and admiration of the New York public that this careful and in many respects remarkably fine representation of ” “Fidelio” was due to him, and was in fact one of the missions he came to New York to fulfill. For “Fidelio” has a place In the affection of music lovers that no other work of its kind can ever hope for-a place of its own. With all that can be said against the fundamental contradictions and conventionality of its form — accompanied spoken dialogue mingled with song and recitative; or against the treatment, symphonic rather than dramatic, to which the orchestra is sometimes subjected in it; or against the “instrumental” treatment of voices of which many have accused it; or against the anti-climax of the final scene-with all this the opera represents, at its finest points, some of the greatest and most heartfelt of Beethoven’s inspiration. Nothing in all musical literature makes a more poignant appeal to the heart or penetrates more deeply to the innermost spring of human emotion, nor has music often been used with a touch so unerring in characterization. Its eloquence, at its highest, is supreme, and its beauty is not staled by the lapse of time or the passing of operatic fashion.

The performance last evening, while it offered a number of points that might be debated, was one of uncommonly vivid dramatic effect and consistency and of much musical beauty. It was marked by the finesse and the subtlety of conception that have given such extraordinary fascination to Mr. Mahler’s other performances here. It was heard by a large audience that was clearly deeply interested and stirred by its many beauties. There had evidently been much pains spent upon it to give it the distinction that is said to have belonged to his Viennese production. Now, Mr. Mahler is a man of strong original ideas of his own. And his treatment of the Wagnerian dramas and “Don Giovanni” has shown that he makes no fetish of great masterpieces and refuses to be bound by tradition or even by the letter of the text. How far such an attitude is justified on the part of a conductor aiming to set an operatic performance in what he deems the most effective manner before the pubic may be open to question. It is certain that in “Fidelio” Mr. Mahler makes a number of changes from accepted traditions and even in certain passages from the orchestration as set down by Beethoven.

The most obvious of these changes is realized in the completely new scenic setting that has been provided, following that which Mr. Mahler devised for Vienna. The first scene is presented, not in the courtyard of the prison, but in a little room, strongly lighted through a deep grated window, and with an evident connection with the penal institution through the door. The courtyard of the prison into which the prisoners are released is a small space, gloomily walled in, with a glimpse of blue sky and tall cypress trees beyond, and a gateway through which the prisoners are allowed to pass. The dungeon in which Florestan is confined seems more a sort of natural cavern than the depths of a great building’s foundations; yet it is darkly realistic. Finally, the last scene is enacted upon what seems to he a high parapet of the prison with a glimpse of distant country beyond. All these scenes are admirably painted and give abundant illusion.

More significant is the division which Mr. Mahler makes of the opera. He drops the curtain once and makes but two acts of the opera, as the score directs. The quick march that precedes Pizzaro’s arrival comes a sort of intermezzo for the change that the new setting makes necessary between the first and second scenes of the first act. Instead of playing the great “Leonore Overture No. 3 as many do after the first act, Mr. Mahler uses it during the change of scene in the second act after the great climax in the dungeon to the final scene in the presence of the Minister. And this performance of the overture, it may be said, was a remarkable one, the achievement of a great conductor; wonderfully thrilling, subtle in its nuances, imposing in its climaxes and eloquent of the dramatic exposition that Beethoven makes in it. The great audience sat as though spellbound while it was played in the dark, and at its close burst into enthusiastic applause, compelling Mr. Mahler to acknowledge the plaudits several times.

There been performances of “Fidelio” at the Metropolitan in which the high individual achievements have been of a higher order. Mme. Morena, who was the Leonora, was head and shoulders above her companions in the cast. She gave a truly noble and distinguished impersonation, full of tenderness, pathos, and grace, and warmly emotional, and her singing had much that was beautiful. Yet it could hot be said that she rose to the full height of the great air “Abscheulicher.” Mr. Burrian’s Florestan was a competent and intelligent piece of acting; not one that strongly aroused the sympathies, either in appearance or in the quality or his singing, which was often hard and unyielding. Nor was the Pizzaro of Mr. Goritz, while it was energetic, deeply impressive in its denotement uncompromising and implacable villainy, and his singing left something to be desired in euphony.

Miss Alten made a capital study of Marzelline and sang with ebullient spirit, as did Mr. Reiss as Jaquino, and Mr. Blass as Rocco was acceptable, excellent in voice, somewhat prosaic–and it is not an eloquent part. As the Minister Mr. Van Rooy had little to do but did it of course with skill and understanding. The concerted numbers, which have so important a part in the structure and musical significance of “Fidelio” were sung with finish and expression, especially the quartet in the first act, and the duet, the trio, and the quartet, which succeeded each other in the scene in the dungeon were made to give that wonderful passage much of its ever-increasing dramatic power and significance.

The chorus of the prisoners had been prepared with much care, but its singing was not notable for its tunefulness. Throughout the whole work the orchestral part was kept in that sphere of delicacy and refinement, of minute perfection of phrasing, nuance, and beauty of tone that has characterized all that Mr. Mahler has done.

Review in The Press:

The star of the evening, unquestionably, not only from the critical point of view, but by popular judgment, was Gustav Mahler, the conductor. It is unusual to see the operatic rank and file aroused to enthusiasm by the man at the helm; unusual at least at the Metropolitan Opera House, and after no less a composition than the Leonore No. 3 overture, which was performed to a darkened house between the first and second scenes of the last act.

Decidedly this was the climax of the evening in point of excellence; it was one of the most superbly effective, most wonderfully weighted, exquisitely balanced and dramatically constructed readings of Beethoven’s overture ever heard in New York. But one hardly expected the mass of operagoers to appreciate that fact as keenly as they did. There was a pause of several seconds as if astonishment and admiration kept the crowd silent; then came a crash of applause. “Bravo, bravo” cried the voices from various quarters of the house, not confined to the top galleries by any means. “Mahler! Mahler!” shouted others, while the great conductor, turning his back to the stage, bowed many times to the enthusiastic throng. Would that our audiences show such approval more often when hearing really great works instead of wasting energy on such evanescent stuff as Puccini’s “Tosca” and “Butterfly,” operas that no one will know by name when Beethoven’s music still lives and delights.