Personal Information

|

||

|

Name

|

Alma Maria Rose

|

|

| Born | 04-04-1944 | Auschwitz-Birkenau |

| Gender | ♀️ Female | |

Parents ( 1 )

|

Father

|

Arnold Josef Rose | |

| Mother | Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler | |

| Siblings |

♂️ Alfred Eduard Rose

|

|

Spouses ( 1 )

|

Spouse

|

Jan Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp | |

Spouses ( 2 )

|

Spouse

|

Vasa Prihoda | |

Events

📍 Auschwitz-Birkenau

Additional Information

|

Additional Info

1926 c. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). Also: Alma Rosé. Relation to Gustav Mahler (1860-1911): A daughter of a sister (niece).

Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) was an Austrian violinist of Jewish descent. Her uncle was the composer Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). She was deported by the Nazis to the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. There, for ten months, she directed an orchestra of prisoners who played to their captors to stay alive. Rosé died in the concentration camp of a sudden illness, possibly food poisoning. Rosé's experience in Auschwitz is depicted in the controversial play "Playing for Time" by Fania Fénelon. Early years Alma Rosé's father was the violinist Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) who was the leader of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (VPO) for 50 years: from 1881-1931 as well as leader of the Vienna State Opera Orchestra and leader of the legendary Rose Quartet. Her mother, Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938), was Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)'s sister. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) was named for Alma Mahler (1879-1964). Marriage Alma grew up to be a violinist. In 1930 she married the Czech violinist Váša P?íhoda (1900-1960). In 1935 the marriage was dissolved. Career Rosé had a highly successful career. Performance at Mahler Festival 1931 Jihlava. In 1932 she founded the woman’s orchestra, Die Wiener Walzermädeln (The Waltzing Girls of Vienna). The concertmistress was Anny Kux, a friend. The ensemble played to a very high standard, undertaking concert tours throughout Europe. Escape from the Nazis and final arrest After the annexation of Austria with Germany in 1938 Alma and her father Arnold, himself a famous violin virtuoso, managed to escape to London in 1939. She returned to the continent and continued to perform in the Netherlands (Grand Hotel Central). When the Germans occupied the Netherlands, she was trapped. A fictitious marriage to a Dutch engineer named August van Leeuwen Boomkamp did not save her; nor did her nominal status as a Christian convert. She fled to France, but in late 1942 when she tried to escape to neutral Switzerland, she was arrested there by the Gestapo. After several months in the internment camp of Drancy she was finally deported in July 1943 to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. Auschwitz Upon arrival in Auschwitz, Rosé was quarantined and became very ill, but was eventually recognized. She assumed leadership of the Mädchenorchester von Auschwitz (Girls Orchestra of Auschwitz). The orchestra had been in existence before Rosé's arrival, a pet project of SS-Oberaufseherin Maria Mandel. Prior to Rosé, the orchestra was conducted by Zofia Czajkowska, a Polish teacher. The ensemble consisted mainly of amateur musicians, with a string section, but also accordions and a mandolin. The orchestra's primary function was to play at the main gate each morning and evening as the prisoners left for and returned from their work assignments; the orchestra also gave weekend concerts for the prisoners and the SS and entertained at SS functions. Rosé conducted, orchestrated and sometimes played violin solos during its concerts. She helped to mold the orchestra into an excellent ensemble, all of whose members survived during her tenure, and after her death, all save two would live to see the end of the war. Rosé herself died, aged 37, of a sudden illness at the camp, possibly food poisoning. The orchestra included two professional musicians, cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and vocalist/pianist Fania Fénelon, each of whom wrote memoirs of their time in the orchestra that were eventually translated into English. Fénelon's account, Playing for Time, was made into a film of the same name. Alma's father, Arnold Rosé, died in England not long after the war ended.

Purposes

For Prisoners

Alma Rosé

Recordings

1914. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944).

1915. Alfred Rose (brother), Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) and Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938).

1924. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). Picture by Dora (Madame d'Ora) Kallmus (1881-1963).

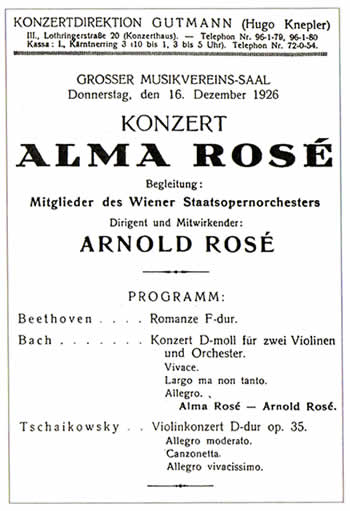

1926. 16-12-1926. Debut Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). Konzerthaus, Vienna, Austria.

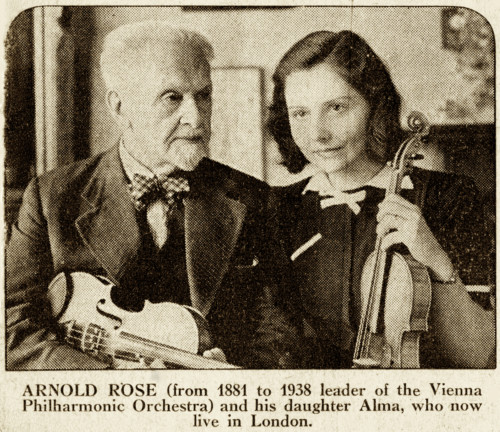

1927. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

1930. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944).

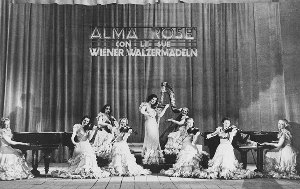

1930. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) and the Wienser Walzermadeln.

1930. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) and the Wiener Walzermadeln.

1930 c. Vasa Prihoda (1900-1960) and Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944).

1933 c. Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938), Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944), Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) and Vasa Prihoda (1900-1960).

Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in a car. 1938. London, 09-1938. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) to her brother Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975) (Alfi). 1938. London, 09-1938. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) to her brother Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975) (Alfi). 1939. 12-01-1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). To Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) and Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975)? Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938) died in 1938.

Ca. 1939. London. Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) and Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). 1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). Letters from The Netherlands (see below):

1939. The Hague, 18-12-1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in the Grand Hotel Central to Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975). 1/4 1939. The Hague, 18-12-1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in the Grand Hotel Central to Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975). 2/4 1939. The Hague, 18-12-1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in the Grand Hotel Central to Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975). 3/4 1939. The Hague, 18-12-1939. Letter from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in the Grand Hotel Central to Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975). 4/4 1940. Letters from Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in the Netherlands.

1943. Auschwitz.

1943. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944). Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz Grave Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944), Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Grinzing cemetery (20-5-6), Vienna, Austria. Grave Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944), Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler (1868-1938) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Grinzing cemetery (20-5-6), Vienna, Austria. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) by Richard Newman. More By 05-1943, the women’s group counted fifteen musicians and the repertoire consisted of a few military marches. Then one day, in July 1943, transport no. 57 from Drancy, France, arrived. Among the women assigned to the infamous Block 10 of the Stammlager, where Dr. Clauberg was performing his sterilisation experiments, there was one with the tattooed number 50381, who was recognised by one of the female inmates, Ima van Esso, as the famous Viennese violinist Alma Rosé. Word quickly reached the camp commandants and soon Alma was given the role of leader of the women’s music ensemble of Birkenau, personally ordered by Maria Mandel, who was nothing short of delighted to have such an addition to her pet project. Before saying any more about what ensued, it is very important to highlight Alma Rosé´s background, in order to facilitate the understanding of how she led her Birkenau ensemble. She was born in Vienna in 1906, as the second child in the family, literally into music aristocracy. Her father, Arnold Rosé, born Rosenblum, himself a Romanian Jew, was the concertmaster of the Vienna Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic, as well as the leader of arguably the best string quartet of that time, the Rosé Quartet. Her mother was Justine Mahler, sister of the composer Gustav Mahler. Alma herself was named after Gustav Mahler´s wife. Another Mahler sibling, Emma, had previously married Arnold Rosé´s elder brother, Eduard, a cellist, whose life later ended in Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín), Czech Republic, after he had got deported there due to his Jewish origin. In the Rosé household, it was a normal occurrence to have a few members of the Philharmonic playing chamber music on Sundays. Alma Rosé was brought up under rules and obedience, not only because of her father, a strict authoritarian, but very much so because of her mother too. Justine had run her brother´s household for years and kept postponing her marriage to Rosé because she didn´t want to give up control over Gustav’s life. They finally married one day after Mahler married Alma Schindler, on Justine´s insistence. Iron discipline was all Alma knew. Endless practice hours with her father since a very early age, always in the shadow of her elder brother Alfred, debut at the Goldner Saal of the Musikverein at the age of 10, great expectations - excellence was implicit and everything short of that considered failure. Arnold Rosé liked the idea of his daughter marrying a famous violin virtuoso, so he practically arranged Alma´s marriage to Váša Príhoda in 1930. However, the liaison did not take too much time to prove unsuccessful and really ended long before 1935, when the divorce was finalised. Alma Rosé´s way of fighting for her own place under the sun, out of the shadow of her elder brother Alfred, and her answer to the burden of the name and tradition behind it was forming her Wiener Walzermädeln (Vienna Waltz Girls) orchestra, with which she toured Europe. She was very strict with her musicians, with high standards, demands and discipline, and she would get very frustrated and furious when things went differently than planned - a trait which persisted until the end of her life. The girls had huge respect for her because of her excellence, but were also afraid of provoking her with mistakes. Until the persecutions started, Alma had lived a glamorous life. However, after the Anschluss, her father was shown the door at the Opera and at the Vienna Philharmonic, something he simply could not understand. There was no place for him due to his Jewish origin, although he had converted to a Christian decades before, as had his wife, and both children were baptized Protestant while infants. Justine died later that year, in 1938, and the frantic struggle to emigrate began, since the Rosés, as Jews, were stripped of all rights and also of those to perform, especially the music of German composers. Alfred, Alma´s brother, left the country first in late September 1938 with his wife, in direction USA and finally Canada, and Alma eventually succeeded in taking her father to England in 1939, via Berlin and Amsterdam, an event that received press coverage. When the money started reaching the low limit, Alma decided she would go back to the Continent, to the Netherlands, to perform and financially help her father. However, the rope around the necks of the Jews of Europe was tightening and, when Alma finally decided it was time to leave, many, if not all escape routes were closed. Her fictitious marriage to August van Leeuwen Boomkamp, a Dutch engineer, was useless too. She refused to live in hiding, as she simply could not bear living without making music, so she opted for an escape plan that was supposed to bring her to Switzerland, through France. She was arrested by the Gestapo in Dijon, along with the young Jewish man who was travelling with her, both with false papers and most probably betrayed by an agent who had infiltrated the escape network. After some time, she was sent to Drancy and a few months later, in the summer of 1943, to Auschwitz. The list for the transport no. 57 displays Alma under a wrong name, Obna Vanleuween, and a wrong birthdate, 8th November 1906, instead of 3rd November. As stated earlier, upon arrival, Alma found herself in the notorious Block 10 of the Stammlager. She was paralysed by what she was thrown into and it took a while until, having been recognised and identified as Alma Rosé, the famous violinist, she was transferred into the Block 12 of the women´s camp in Birkenau, among the musicians. Upon her transfer and the appointment to the position of the leader of the ensemble and according to the camp hierarchy, Alma was given the rank of a kapo, which, on paper, put her alongside all kinds of opportunists and criminals who filled that position across the camp and were known for cruelty that could put them right by the side of the SS. Needless to say, Alma was not an addition to that category. She used the position that allowed her to have a tiny room in Block 12 to retreat into her inner world and fight, in her own way, against the horror into which she was thrown. She was also slightly better dressed than a regular prisoner. Maria Mandl´s decision to name Alma the conductor of the ensemble caused stirring antagonism towards Alma among the Polish members, who supported Czajkowska. However, it all soon calmed down and Alma could deal with what she found upon her transfer, which wasn´t really much – a group of girls and women who played miserably on instruments that would never found their place together in any orchestra. Alma found herself faced with the impossible task of making an chestra out of such a group. To a top-level professional musician it meant a lot of frustration, added to the already unthinkable situation of being in an extermination camp like no other, surrounded by death every minute of every day. With Alma´s arrival, the band underwent a significant transformation. The number of members grew. Very few of them were actually proper musicians; others were girls who happened to learn to play an instrument at school. The combination of instruments was unlikely: mostly violins, then guitars, mandolins, accordions, flutes, percussion. The band was complete with a few singers and copyists. There were no proper bass instruments because the only cellist they had, Maria Kröner, died of typhus. Then in the winter of 1943, a prison train brought new inmates to Birkenau, among them the then-18-year-old Anita Lasker, Breslau-born cello student, arrested for forging papers for French prisoners of war and trying to escape to Paris with her elder sister Renate. She was lucky enough to not undergo the selection process, given the fact that she arrived as a convicted criminal directly from prison, but she certainly wasn´t spared the shaving and tattooing. Apart from being totally overwhelmed by the indescribable new surroundings, the surreal continued when – while standing stark naked, in every possible sense of the word, shaved and marked like an animal – she was asked by one of the prisoners what her profession was before coming to Birkenau. As Anita Lasker, today Wallfisch, remarked many times, she didn´t know why she said it, but she said she played the cello. Nothing could have prepared her for what ensued. […] The reaction was so much more astonishing, in that it was totally unexpected. She said: “That is fantastic! You will be saved! Stand aside, remain there and wait! You will be saved!” So Anita waited and waited, all alone, until the door of the Block opened again and in came a woman in a camel-hair coat who looked so elegant that the 18-year old wasn´t sure if it was a guard or a prisoner. She introduced herself as Alma Rosé and, thrilled that Anita was a cellist18, asked where she studied and with whom. Anita continues: The scene was like in a dream. The last thing I was expecting when I arrived to Auschwitz was an interrogation about my cello playing! I was still totally naked – with a toothbrush. Alma stated how glad she was that I was there and again I heard the words: “You will be saved.” Anita was transferred to the Quarantine-Block, for many new arrivals the very last station in their lives, but she was later picked out and taken to the music Block. There she played in front of Alma and was subsequently admitted into the orchestra. By that time, Alma had already been half a year at the helm of the ensemble and had no illusions about where she was – if there had been any before the arrival to Auschwitz, the process of being stripped naked, shaved, tattooed, sent to the experimental block, together with the horrors she saw in the days she spent there before joining the musicians made sure that these illusions disappeared. Everybody, however, was struck by the elegance and dignity she showed from the early days of her tragedy and never lost, even in the most gruesome moments. At the end of January in 1944, the ensemble got a new member – a French singer and pianist, Fania Goldstein, known as Fénélon. She was arrested in Paris and deported to Auschwitz and was taken into the women´s Lagerkapelle, as the ensemble was called. Apart from being a singer, she was a good addition to the group, in that she was a quality orchestrator, a skill helped expand the repertoire. In short, she was one of the few trained musicians in the Kapelle. According to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, Fénélon was quite agreeable in the camp, talented to invent stories with which she would entertain the fellow musicians and very good in orchestrating – Anita particularly remembers one evening, during which the women secretly played Beethoven´s Pathétique, arranged by Fénélon, only for their own pleasure. What came after the war, though, shocked all the surviving members of the orchestra. In 1976 Fénélon published a book entitled “Sursis pour l´orchestre”, which portrayed her as the hero in the orchestra and painted a very ugly portrait of Alma. Significant portions of the book are simply figments of her imagination, including parts of her own past before Auschwitz. A notorious After the publication of the book, the other survivors cut all contact with their former colleague, deeply offended by the distorted facts. Unfortunately, “Sursis pour l´orchestre” has lived through many editions in many different languages, often published without any editorial note on the controversy regarding its content, and is still the point of departure for anyone who doesn´t bother to dig deeper into the matter, an enormous danger for preserving the memory of these events. The truth, however, resides elsewhere. Alma was not an easy-going person – that much was true. And when it came to music, there was no compromise. She insisted that all women be concentrated on what they were playing and she would get furious when it wouldn´t be the case. She would also occasionally punish the women for not playing well. The reasons for Alma´s harshness and discipline are manifold. A significant amount lies in her background, the way she grew up and the heritage she was born into. She was very devoted to her music making, everything had to be right. She was simply giving her whole self to the music and expected no less from those who played with her. Arnold Rosé, her father, stated that she was “possessed of Mahler´s spirit” and, although she was only five years old when her uncle died, this statement was not too far from the truth. She asked no more than what she was giving - her commitment was full and she expected the same from her fellow musicians. Such attitude did not win her much popularity, as it didn´t to her uncle either. Like him, Alma worked according to very high standards and she stuck to them, no matter the situation or circumstances, any time, any place, never stepping away. They both owed it to the score, but also – and this is a very important detail – to themselves. It is a concept not always easy to understand, especially to non-artists, and that is one of the answers to why reactions are always divided, particularly in the context of such an extreme situation like music-making in an extermination camp. For Alma Rosé, music was not merely a profession; it was a way of life. She was stripped of a lot of things in Auschwitz, but no one could have stripped her of music and in it she sought the refuge from the horror that surrounded her. She was sensible enough to realise precisely where she was and that there was no escape from such a place. She also knew that giving in to fear and despair meant dying before death and an episode told by Anita Lasker-Wallfisch illustrates Alma´s attitude to what was going on around her: She [Alma] was very cross with one of the people who cried, she was only 16, she saw her aunt passing by to the gas chamber and she cried. And she [Alma] gave her a slap and said: “We don´t cry, here we don´t cry! Here grateful to her, she made me harder.” Yes, you can´t cry, that´s a luxury. She reduced our vision to what was just happening there, in that Block, we must play that stupid piece well. As in everything else, Alma demanded the full commitment and it had as a consequence the fact that the women had little time to dedicate to the smoking chimneys outside – they were doing their best to hit the right note. Eventually, this effort, regardless of Alma´s insistence and pushing, helped the women realise that they were not really playing for the Nazis, even when these happened to barge into the music Block and demand a particular piece of music to be played, but for themselves, their own sanity and the hope that perhaps they would survive. Alma Rosé was such a dignified person that just by her appearance she commanded respect. It was a surreal sight in Birkenau, but she carried her tragedy with so much grace and dignity that nobody remained indifferent. Her The SS were stunned by Alma´s remarkable dignity, so much that they called her “Frau Alma”, something unthinkable for a Jew in Birkenau. She was very likely sensible to the point to know how far she could go, being aware that, despite all the respect she enjoyed, she was walking on a thin rope. She used her position very carefully, to protect her Kapelle and make the lives of the members at least a bit more bearable. She convinced the SS that it was not possible to play in harsh winter conditions without some form of heating because also the instruments would suffer and be ruined, so they gave her a sort of a heating device for the music Block, a privilege no other Block of regular prisoners had. Thanks to Alma´s effort, the women were also not forced to endure hours and hours of roll call torture in harsh weather: they were allowed to perform that insane duty inside their Block. However, playing for hours and hours with very little to eat and drink was taking its toll, along with typhus and various other sicknesses and debilitating conditions, and Alma performed another miracle – she talked the SS into allowing the women a break after their miserable lunch, so they could rest. With the increase of the repertoire, the demand for copyists was also getting higher and Alma did everything to take as many women into the Kapelle as possible, knowing what it meant to all of them. However badly a woman played, she was never thrown out. She was given another task inside the band, but never thrown out. Alma also did everything she could, so the women would not be gassed because of being ill and Violette Jacquet, later Silberstein, a violinist, remembers Alma lying to an SS that she was one of her best violinists, so that she would not be taken away because of being sick with typhus. Many gossips about the Kapelle were circling in the camp – the musicians were sarcastically referred to as “the ladies of the orchestra” because they had a sort of uniform for “official concerts”, and the fact that they were not going out to factories for slave labour was a motive to scorn them, especially when they had to play in front of an audience comprising the SS. These gossips, many of which had to do with Alma, caused the birth of a lot of myths about the orchestra, which is quite evident in the statement of Dr Lucie Adelberger, an inmate and physician at the Krankenrevier (hospital Block) at Birkenau: Music was something like a lapdog of the camp´s administration, and the participants were clearly in its good graces. Their block was even better tended than the clerk´s office or the kitchen. Food was plentiful, and the girls from the orchestra were neatly attired in blue cloth dresses and caps. The musicians were quite busy; they played at the roll call, and the women who were returning from work exhausted had to march to the rhythm of music. Music was ordered for all official occasions: the speeches of the SS camp leaders, transports, and hangings. In between, the musicians served to entertain the SS and the inmates at the infirmary. In the women´s camp, the orchestra played in the infirmary every Tuesday and Friday afternoon undisturbed by all the goings-on and selections around it. Not only wasn´t the food plentiful, the Block so well-tended and the women so insensitive to what was going on around them, but here there´s a mention of another myth that is strongly disputed by many members of orchestra and that is that the Kapelle (both men´s and women´s) played at the selections and executions. To play at a selection and during a selection are two very different things, but unfortunately, too many people tend to see particular events as they please, choosing more notorious or, if one likes, more scandalous interpretations, just for the sake of sensation. In the case of transports and selections, especially during the arrivals of trains with tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews, one thing is a naked fact: music could be heard from the selection point. However – and here we come to an extremely important detail – the Kapelle, men´s or women´s, was never directly at the ramp and never played to purposely accompany the arrivals of the transports or the selection process. The camp orchestras performed their regular duties outside the Block (playing marches while the inmates were going out or coming back to the camp), which means that the people throughout the camp, including those at the selection ramp, could hear the music. It is enough to look at the aerial images of the camp to realise that the gate, the ramp, the rail tracks, the Blocks, the gas chambers and crematoria were not kilometres apart. Many things were going on in the camp at one given moment and, due to the number of transports arriving especially in 1944, it was inevitable that it happened that music was heard during a selection. The musicians could see the Alma Rosé did what best she could in the circumstances she was thrown into. The ever more frequent transports and gassings, especially the total extermination of the Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín), Czech Republic, Jews from the “family camp” and the endless gassing of the Hungarian Jews, made her go deeper into her music. These events hit her very hard and she completely withdrew into her inner world, isolating herself into the excellence of her music, in which she was looking for the means of survival. She was attached to the members of her Kapelle, a nucleus counting at one point between forty and fifty women, and gave them compliments, when in her opinion they deserved it. Her greatest praise was to tell them that what they had just played would have been good enough for her father. Helena Spitzer Tischauer, known in the camp as Zippy, stated: Alma once said, “I will never go back to my Wiener Mädchen (or whatever she called that), I will take you, girls, all over Europe and we are going to play!” You know what that meant to us? However, although Alma never really abandoned hope of leaving the camp, she wasn´t going to see it happen. On the evening of 2nd April, after a dinner with Frau Schmidt from the clothing department, Alma returned to the music Block not feeling well. Many times before that she had experiences splitting headaches, but this was something much more serious, going downhill very quickly. Alma´s closest friend from the camp, Dr Margita Svalbová, known as “Manci” and “Manca”, was with her till the end. The violinist was taken to the hospital Block and various attempts to diagnose her condition were made. The SS feared an epidemic; on 4th April, the notorious Dr Josef Mengele ordered a spinal tap, to check for pneumonia and meningitis. Unfortunately, there was nothing that could have saved Alma and she died later that evening, from still undetermined causes, which has fuelled all kinds of theories ever since, ranging from poison to botulism. Mandel allowed the women of the orchestra to say goodbye to their leader, a gesture without precedence in Auschwitz. It was done, but absolutely not the way Fénélon described it, with flowers and pathetic scenes from the SS. Alma´s death was a huge blow for the orchestra, not only because no other person could keep up with the standards she had set, but also because of the amount of respect she had been given. She was succeeded by Sonia Vinogradova, but the results were far from what Alma had managed to obtain. The fear of being gassed grew, especially when the SS started losing interest in the orchestra with the advance of the Soviet troops. In late 1944, the Nazis started evacuating Auschwitz and taking measures to leave as little evidence as possible about the mass murders they had been committing. The Jewish members of the women’s Lagerkapelle from Birkenau were transported to Belsen. The last music they played was in Birkenau, in Belsen there was none. The women stuck together and kept encouraging each other in the horrible Belsen months, and all except two of them lived to see the entrance of British troops into the camp on 15th April 1945. The SS had created the orchestra for their own deranged purposes, but in so doing they inadvertently gave its members a mode of survival. While most of the prisoners who were not part of the orchestra did not look to its members with approval, often accusing them of collaborating with the SS, being a part of the Lagerkapelle gave these women an identity back and helped them hold on in the battle to survive, both physical and mental. Alma’s attitude and standards helped them to realise that, regardless of the fact that their audience was frequently the SS, they did not play for their potential executioners, but for themselves. Alma Rosé literally saved their lives by taking them into the Lagerkapelle, and saved their minds by forcing them to think about the notes and not look through the window and see the chimneys of the incessantly working crematoria. Although during the time in Auschwitz-Birkenau they did not really love that harsh and disciplined woman (they were often angry with her, but nonetheless always nurtured respect towards her), in retrospect the great majority of the women from the Lagerkapelle led by Alma Rosé came to understand her and feel deeply grateful and indebted to her. Asking any of the survivors today the question what they think about Alma, the answer would always be: “She saved us.” |