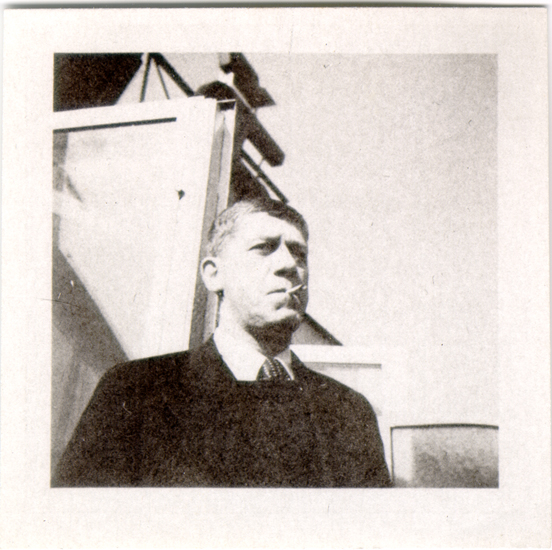

1909. Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

- Profession: Painter, poet, playwright.

- Residences: Vienna, Prague.

- Relation to Mahler: Love affair with Alma Mahler (1879-1964).

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 01-03-1886 Pochlarn, Austria.

- Died: 22-02-1980 Montreux, Switzerland.

- Buried: Clarens cemetery, Clarens, Vaud, Switzerland.

- Fragment (Audio, German, duration 01:48): Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) about about his life.

1912. La Giocona. Portrait of Alma Mahler (1879-1964) by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

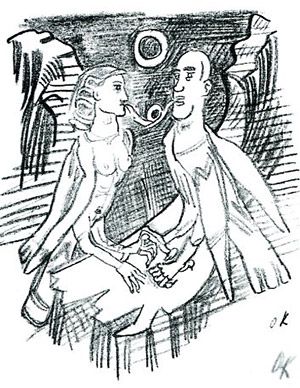

1912. Double portrait of Alma Mahler (1879-1964) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980) by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

1913 The Bride of the Wind (Die Windbraut or the Tempest) by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). It is housed in the Kunstmuseum Basel. Kokoschka’s best known work, is an allegorical picture featuring a self-portrait by the artist, lying alongside his lover Alma Mahler (1879-1964). Size: 181 cm x 221 cm.

1913. Alma Mahler (1879-1964) by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

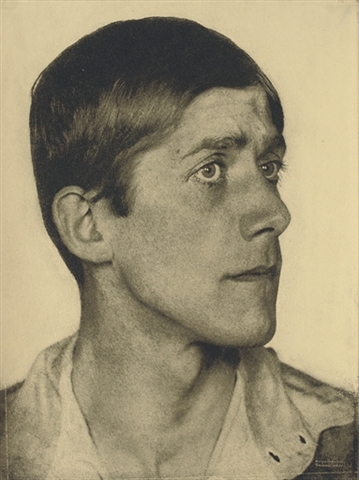

Oskar Kokoschka was an Austrian artist, poet and playwright best known for his intense expressionistic portraits and landscapes. He was born in Pöchlarn, second child to Gustav Josef Kokoschka, a Czech goldsmith, and Maria Romana Kokoschka. His older brother died in infancy in 1887; he had a sister, Berta (born in 1889) and a brother, Bohuslav (born in 1892). Oskar had a strong belief in omens, spurred by a story of a fire breaking out in Pöchlarn shortly after his mother gave birth to him. Kokoschka’s life was not easy mainly due to a lack of financial help from his father. They constantly moved into smaller flats, farther and farther from the thriving center of the town.

Concluding that his father was inadequate, Kokoschka drew closer to his mother; he felt that he was the head of the household and continued to support his family when he gained wealth. Kokoschka entered secondary school at Realschule, where emphasis was placed on the study of modern subjects such as science and language. Kokoschka was not interested in his subjects, as he found he only excelled in art, and spent most of his time reading classic literature during his lessons. This education of classic literature is said to have influenced his artwork.

One of Kokoschka’s professors suggested he pursue a career in fine art. Against his father’s will, Kokoschka applied to Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Vienna, where he was one of three accepted out of 153 applicants. Kunstgewerbeschule was an extremely progressive school that focused mainly on architecture, furniture, crafts and modern design. Unlike the more prestigious and traditional Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, Kunstgewerbeschule was dominated by instructors of the Vienna Secession. Kokoschka studied there from 1904 to 1909, and was influenced by his professor Carl Otto Czeschka in developing an original style.

Among Kokoschka’s early works were gesture drawings of children, which portrayed them as awkward and corpse-like. Kokoschka had no formal training in painting and so approached the medium without regard to the “traditional” or “correct” way to paint. The teachers at Kunstgewerbeschule helped Kokoschka gain opportunities through the Wiener Werkstätte or Viennese Workshops. Kokoschka’s first commissions were postcards and drawings for children. Kokoschka said that it gave him “the basis of his artistic training”. His early career was marked by portraits of Viennese celebrities, painted in a nervously animated style.

Kokoschka had a passionate, often stormy affair with Alma Mahler. It began in 1912, shortly after the death of her four-year-old daughter Maria Mahler and her affair with Walter Gropius. After several years together, Alma rejected him, explaining that she was afraid of being too overcome with passion. He continued to love her his entire life, and one of his greatest works, The Bride of the Wind (The Tempest), is a tribute to her. The poet Georg Trakl visited the studio while Kokoschka was painting this masterpiece. Kokoschka’s poem Allos Makar was inspired by this relationship.

1914. Illustration for the poem Allos Makar by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

He volunteered for service as a cavalryman in the Austrian army in World War I, and in 1915 was seriously wounded. At the hospital, the doctors decided that he was mentally unstable. Nevertheless, he continued to develop his career as an artist, traveling across Europe and painting the landscape.

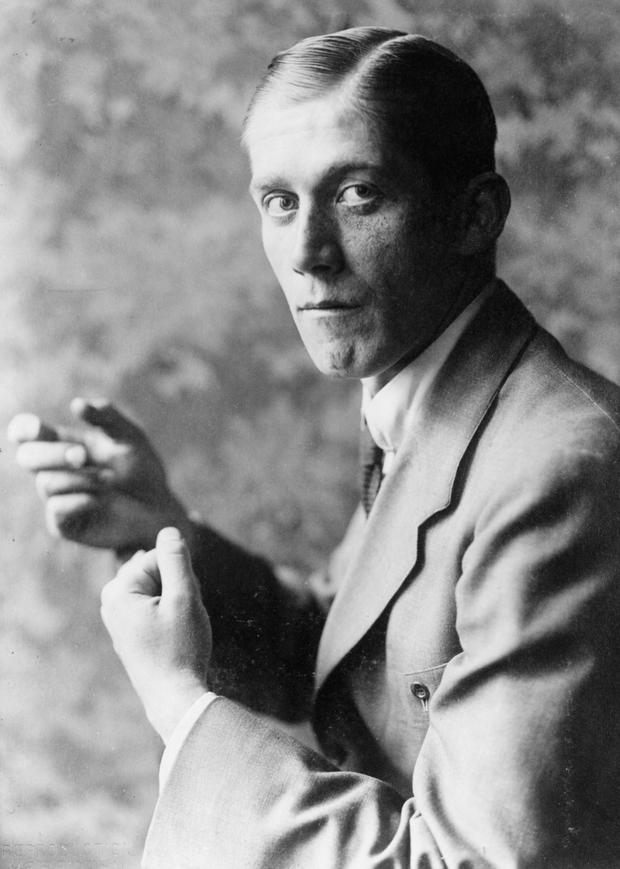

1915. Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

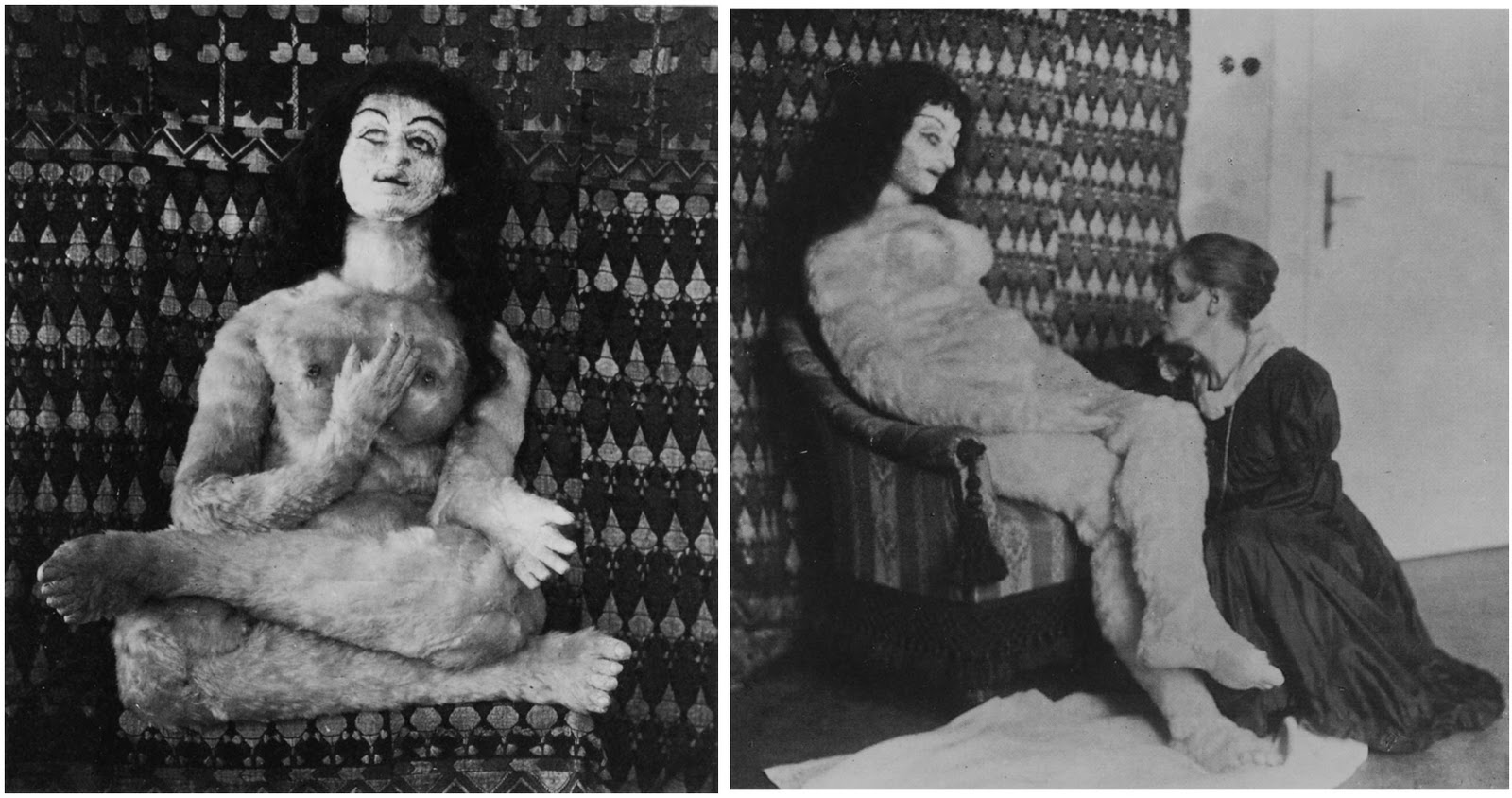

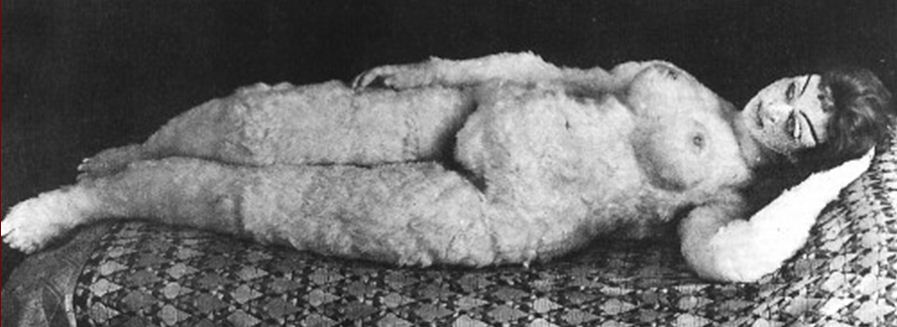

He commissioned a life-sized female doll in 1918. Although intended to simulate Alma and receive his affection, the gynoid-Alma did not satisfy Kokoschka and he destroyed it during a party.

1918. Alma doll by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

Deemed a degenerate by the Nazis, Kokoschka fled Austria in 1934 for Prague. In Prague his name was adopted by a group of other expatriate artists, the Oskar-Kokoschka-Bund (OKB), though he declined to otherwise participate. In 1938, when the Czechs began to mobilize for the expected invasion of the Wehrmacht, he fled to the United Kingdom and remained there during the war. With the help of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia (later the Czech Refugee Trust Fund), all members of the OKB were able to escape through Poland and Sweden.

During World War II, Kokoschka and his wife lived in Ullapool, a village along the Wester Ross of Scotland for several summer months. There he drew with colored pencil (a technique he developed in Scotland), and painted many local landscape views in watercolour. While in Ullapool, Kokoschka painted a painting of his friend, wealthy industrialist Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, Uncle of Maria Altmann. The painting still hangs at the Kunsthaus Museum in Zurich. Kokoschka became a British citizen in 1946 and only in 1978 would regain Austrian citizenship. He traveled briefly to the United States in 1947 before settling in Switzerland, where he lived the rest of his life. He died in Montreux on 22 February 1980.

Kokoschka had much in common with his contemporary Max Beckmann. Both maintained their independence from German Expressionism, yet they are now regarded as its supreme masters, who delved deeply into the art of past masters to develop unique individual styles. Their individualism left them both orphaned from the main movements of Twentieth Century modernism. Both wrote eloquently of the need to develop the art of “seeing” (Kokoschka emphasized depth perception while Beckmann was concerned with mystical insight into the invisible realm), and both were masters of innovative oil painting techniques anchored in earlier traditions.

More on Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler

When Gustav Mahler died in 1911, his widow Alma first sought comfort in the arms of her already-lover Walter Gropius. However, Alma still harbored resentment that Gropius had intentionally misaddressed an envelope and thus exposed their affair to Gustav. In doubt about their future, Alma engaged in a brief but passionate affair with the Viennese biologist Paul Kammerer. Kammerer, in the event, turned out to be a rather possessive not to mention downright morbid chap, so she turned her attention to the young and highly eccentric painter Oskar Kokoschka.

Kokoschka was a key figure in the development of the Expressionist school of painting and simultaneously an accomplished dramatist. But he was also volatile, angry, aggressive and violent, and the local press called him “the wildest beast of all.” His paintings frequently prompted the analogy of X-ray films and he had the uncanny ability to turn any party or gathering into a massacre!

They first met in 1912, when Kokoschka spontaneously produced a drawing of Alma while she was playing the piano. “Suddenly,” Alma reports, “he pulled me into his arms. For me it was a strange, almost shocking and violent hug.” Hours later he asked her to become his wife, an offer she politely declined. Nevertheless, their unbridled passion over the next 3 years was only interrupted when Alma posed as a model for his paintings. Kokoschka was working on a double portrait in which Alma wears a red nightie. Alma later recalled, “I was once given a flame-red night gown. I didn’t like it due to its overpowering color. Oskar took it from me right away and from then on went around his studio wearing nothing else.

He wore it to receive his astounded visitors and was to be found more in front of the mirror than in front of his easel.” Once the painting was finished, it was featured at the 26th Exhibition of the Berlin Secession in the spring of 1913. Walter Gropius was one of the organizers of the event, and we might well imagine his surprise at seeing his lover publically holding hands with Kokoschka! Gropius had always suspected that Alma was keeping secrets about her relationship with Kokoschka, but being confronted by the truth in such a public way affected him deeply.

But things had gotten somewhat edgy in Vienna as well. Kokoschka was plagued by obsessive jealousy. He waited until 4 in the morning outside her apartment to make sure that no boys emerged in the dead of night. Alma had reverently arranged a number of her photographs around a bust of Gustav Mahler’s head, and Kokoschka would passionately kiss the photographs to spite Gustav. Even Kokoschka’s mother got involved, writing to Alma, “If you see Oskar again, I’ll shoot you dead!” They still were unable to control their passion, however, and Alma reports, “On a stormy tormented day when he passionately, but entirely selfishly loved me, the world melted away suddenly, and I have since been convinced of an outer-worldly existence.” After emotionally tumultuous trips to the Swiss Alps and Naples, Kokoschka fashioned his most famous painting of their relationship. Die “Windsbraut” (The Tempest) shows the lovers side by side sheltering from a ferocious storm. Alma looks peaceful and content, but Kokoschka’s face shows signs of worry. Maybe he realized that his relationship with Alma was coming to an end.

Things got even more complicated when Alma became pregnant with his child. Her decision to abort caused an irrevocable rift, one from which Kokoschka was never able to fully recover. Terminally depressed, he volunteered for the front lines in WW I and was seriously wounded in Russia in 1915. Meanwhile, Gropius was recovering in a Berlin hospital from wounds sustained in the war. Alma rushed to his side and “the days we spent with tearful questions, the nights of tearful answers. He could not get away from my relationship with Kokoschka.” Somehow, Gropius managed to leave Kokoschka behind, and he married Alma in 1915.

The news of Alma’s marriage to Gropius devastated Kokoschka. In deepest desperation, he ordered a life-size doll from the Munich doll-maker Hermine Moos. The doll was to resemble Alma in every little detail, including “the incipient hollows and wrinkles that are important to me. Please make it possible that my sense of touch will be able to take pleasure in those parts where the layers of fat and muscle suddenly give way to a sinuous covering of skin.” The final product, rather predictably, proofed to be a disappointment as it could scarcely fulfill Kokoschka’s erotic and sexual desires. Kokoschka writes, “After I had drawn it and painted it over and over again, I decided to do away with it. It had managed to cure me completely of my passion. So I gave a big champagne party with chamber music, during which my maid Hulda exhibited the doll in all its beautiful clothes for the last time. When dawn broke—I was quite drunk, as was everyone else—I beheaded it out in the garden and broke a bottle of red wine over its head.”

His expressionist drama Orpheus and Eurydice of 1918 also reflects his failure of his love for Alma. It was set to music by Alma’s son-in-law Ernst Krenek as an opera in three acts, Op. 21. Kokoschka was Orpheus, Alma was Eurydice, and Anna Mahler was Psyche. And wouldn’t you know it, Gustav Mahler appeared as Pluto, god of the Underworld!

The doll

Upon returning home from World War I, Oskar Kokoschka found that his lover, Alma Mahler, had married another man. In response, he commissioned the creation of a life-size doll to match Mahler’s exact proportions. Kokoschka provoked rumor and scandal as he escorted his doll to the opera, held parties in its honor, and hired a maid to dress and service it. This provocative public performance inspired rampant speculation about what else, exactly, Kokoschka did with the doll. The doll met its “unnatural” demise when one of Kokoschka’s parties got out of hand. Police questioned Kokoschka in the morning about a murder; a beheaded and bloody body was reportedly seen outside his home. Evidently it was the naked, wine-splattered doll, which had somehow lost its head during the revelries of the previous evening.

This was the story that Kokoschka and his critics, both then and now, loved to tell, embellishing racy details, speaking to fetishism, sex dolls, pranks, and occasional misogyny. While titillating, Kokoschka’s tumultuous relationship with Mahler and his spectacle with the doll mean little for scholars of modernism unless we can connect them to Kokoschka’s project as an artist. Indeed, much less discussed than the doll episode are the three “portraits” Kokoschka painted of the doll, and their connection to it.

1918. Alma Doll by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

The first, Woman in Blue, 1919, is still considered Kokoschka’s masterpiece of this period, though it is seldom analyzed in detail; and the two latter, Painter with Doll, 1920–21, and At the Easel, 1922, are among Kokoschka’s numerous self-portraits, and rarely noted by critics.

1919. Woman in blue by Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980).

Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980). Color “for your winter of exile’ is pencilled on the watercolor which Maria Caroline Rosé-Schmutzer (1909-1999) treasures. It was sent by the painter to professor Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975)‘s father, Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946), the eminent concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (VPO) who fled to England.