No photo. Blond.

- Profession: Soprano.

- Residences: Kassel, Rotterdam (1886), Cologne (1888).

- Relation to Mahler: Love affair with Gustav Mahler in Kassel (1883-1884). An ardent, but ultimately unfulfilled, love affair with soprano Johanna Richter led Mahler to write a series of love poems which became the text of his song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (“Songs of a Wayfarer”). See Poems.

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 18-08-1859 Berlin. (1860?) (Not related to Hans Richter (1843-1916))

- Address Kassel (until 1887): House Johanna Richter, Kolnische strasse No. 13.

- Address Danzig (1943): House Johanna Richter, Holzmarkt No. 11.

- Marriage: ?

- Died: 00-00-1943 Danzig, Poland. Aged 85.

- Buried: ?

Also: Johanna Emma Richter, Johanna Jeanne Richter.

- Berlin, Germany.

- Danzig, Poland.

- 1881-1882: Mainz, Germany.

- 1882-1883: Bremen, Germany.

- 1883-1886: Kassel, Germany. House Johanna Richter.

- 1886-1887: Grosse Deutsche Oper, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- 1887-1891: Cologne, Germany.

- 1891-1892: Stadttheater Olomouc, Germany.

- 1892-1893: Konigsberg, Germany.

- 1895-1906: Stadttheater, Danzig, Poland.

- 1906-0000: Singing teacher, Danzig, Poland.

Inspiration for Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen.

- 02-04-1886 Letter Johanna Richter (1858-1943) to Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

- 00-08-1884 Mahler wrote Friedrich Fritz Lohr (1859-1924) about his relationship with Johanna Richter (1858-1943).

Another episode that was to have far-reaching consequences for Mahler’s life and work was his affair with the singer Johanna Richter. Initially there seem to have been two options of an erotic nature that presented themselves to the assistant conductor, whose appointment coincided with that of two young sopranos, Virginia Naumann-Gungl and Johanna Richter herself. There is some evidence that Mahler’s feelings were first fired by Naumann-Gungl, but she was already married and the mother of two children and, indeed, considerably older than Mahler. In short, she was less attainable.

With Johanna Richter, by contrast, the situation was very different. Although we know little about her and have no idea what she looked like, making it impossible to say whether there is any truth to the claim that she was a noted beauty, it seems likely that she was indeed physically attractive as Mahler’s susceptibility to female beauty is clear from photos of the young Alma Mahler and of all the other women with whom he was in any way associated.

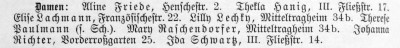

Johanna Richter (1858-1943) in Konigsberg Neuer Theater-Almanach, 1893. Königsberg (until 1946 officially: Königsberg in Preußen) was a city in the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, the Duchy of Prussia, the Kingdom of Prussia and Germany until 1946. After being largely destroyed in World War II by Allied Forces and then annexed by the Soviet Union thereafter, the city was renamed Kaliningrad, and few traces of the former Königsberg remain today.

Johanna seems to have been more or less the same age as Mahler and was a coloratura soprano who excelled in parts such as Mozart’s Konstanze and the Queen of the Night but whose repertory also included Leonora in Il trovatore and even Wagner’s Venus. She was a popular favourite with Kassel audiences and also with local critics. It appears that there were initial misgivings about her vocal technique, but these were quickly silenced, and we may assume that Mahler worked closely with her: it was no doubt at this period in his career that he developed his partial understanding of vocal technique and of voices in general, an understanding that can be observed on repeated occasions in the course of his later career.

Johanna Richter’s subsequent career was far from insignificant. She left Kassel a year after Mahler and sang first in Rotterdam and then in Cologne, where she remained a member of the local ensemble for a period of many years, subsequently appearing in smaller houses and ending her professional career in around 1905, while remaining active as a teacher. She died in Danzig in 1943.

It is clear from his letters to Löhr that Mahler fell in love with Johanna Richter as soon as he arrived in Kassel, leading to a period of the most turbulent emotional upheaval. It was the first genuinely intense experience of love that he had known and at the same time a liaison that brought himmore pain than pleasure, a point that emerges not from any direct evidence, for the only surviving letter from Johanna Richter to Mahler is decidedly non-committal, but from Mahler’s letters to Löhr, among others, in which he reports on the highs and, more frequently, the lows of his liaison. It transpires from these letters that Mahler was exposed to a veritable whirlwind of emotions in which fear prevailed over hope. His own surviving account of the relationship gives the impression of a via dolorosa, a time of a ‘continuous and altogether intolerable struggle’. On his return to Kassel following the summer break of 1884, he told Löhr that he was once again ‘in thrall to the terrible old spell’.

Johanna Richter seems to have expended all the wiles of feminine coquettishness on Mahler, leaving the completely inexperienced assistant conductor utterly helpless, an observation that implies no moral judgement, as the ability to reconcile the career of a singer with an affair involved a difficult balancing act, given the unsettled life led by such singers and the risk of an unwanted pregnancy that might put an end to that career. The course of Mahler’s relationship with Johanna Richter may be illustrated by a passage from a letter that he wrote to Löhr on 1 January 1885. He had spent New Year’s Eve with the soprano:“I spent yesterday evening alone with her, both of us silently awaiting the arrival of the new year. Her thoughts did not linger over the present, and when the clock struck midnight and tears gushed from her eyes, I felt terrible that I, I was not allowed to dry them. She went into the adjacent room and stood for a moment in silence at the window, and when she returned, silently weeping, a sense of inexpressible anguish had arisen between us like an everlasting partition wall, and there was nothing I could do but press her hand and leave. As I came outside, the bells were ringing and the solemn chorale could be heard from the tower.”

As so often with the young Mahler, his effusive style has a literary ring to it, in this case an obvious allusion to a passage from Tannhäuser’s Rome Narration: ‘The new day dawned; the bells were ringing – celestial songs came floating down.’ Appropriately enough, Mahler concludes his description with a clear reminiscence of Heine: ‘Ah, dear Fritz – it was all just as if the great director of the universe had intended it all to be artistically apt. I spent the whole night crying in my dreams.’ But such effusions did nothing to move the relationship forward.

Mahler was left to traverse his vale of tears alone: ‘I am torn apart, my heart is bleeding, all is lost’ – these are the phrases that keep on recurring. Mahler addressed several poems to Johanna Richter, the final line of the first of them already containing a reference to a ‘solitary wayfarer’and illustratingthe link with the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. Mahler composed this set of four songs, probably in December 1884, and dedicated them, at least tacitly, to Johanna Richter. There were originally six poems, all of them written by Mahler himself, but he set only four of them. The two that were not set to music include the following, a poem that offers arguably the most striking illustration of the composer’s inner vacillation between the cynicism of Jean Paul’s Schoppe in Titan and the openness of the twin brothers Walt and Vult in his Flegeljahre, while also including allusions to some of Wilhelm Müller’s poems that Schubert set to music in Winterreise:

Die Nacht bricht mild aus stummen ewigen Fernen

Mit ihren tausend goldenen Augen nieder,

Und müde Menschen schließen ihre Lider

Im Schlaf, auf’s neu vergessnes Glück zu lernen.

Siehst du den stummen fahrenden Gesellen?

Gar einsam und verloren ist sein Pfad,

Wohl Weg und Weiser der verloren hat

Und ach, kein Stern will seinen Pfad erhellen.

Der Weg ist lang und Gottes Engel weit

Und falsche Stimmen tönen lockend, leise –

Ach, wann soll enden meine Reise,

Wann ruht der Wanderer von des Weges Leid?

Es starrt die Sphynx und droht mit Rätselqualen

Und ihre grauen Augen schweigen – schweigen.

Kein rettend Wort, kein Lichtstrahl will sich zeigen –

Und lös’ ich’s nicht – muß es mein Leben zahlen.

This painful relationship lasted until Mahler left Kassel and seems never to have transgressed the bounds of formal, polite behaviour, for all that Mahler would have liked it to have done so. In the only surviving letter that Johanna wrote to Mahler after he had already left for Praag, she addresses him as her ‘dear good friend’ and uses the respect for pronoun ‘Sie’. Mahler spent his final hours in Kessel with Johanna in June 1885, but neither party was capable of finding a way out of the hopeless crisis of their unrequited love.

More

In its final published form (in 1899), this symphony only included four movements – Mahler had discarded the formerly second movement “Blumine” (Flowerine), after criticism following the earlier performances in 1889, 1893 and 1894. However, Reinhold decided to include this movement (which had been lost until 1966) in this recording in its original place of the symphony structure, because in his opinion (and in the opinion of several Mahler scholars) this movement introduces musical themes and motives which are essential for the rest of the symphony. Reinhold also decided to keep the original titles of the movements. Mahler had discarded these programmatic titles too, so as not to influence the audience with preconceptions but rather let the music speak for itself. However, audiences in our current times are different from those in Mahler’s time, and are unlikely to have wrong expectations.

On the contrary: these subtitles which are derived from Jean Paul’s novel “Titan”, poignantly highlight the overall mood of each movement and are so much more appropriate than the tempo instructions for the conductor (e.g. “langsam schleppend”) which in most conventional recordings and performances serve as titles for each movement. Therefore, this edition of the Symphony No.1 bears the titles which Mahler himself gave in the original program notes of the early performances of this work. The overall title “Titan” which sometimes is given to this symphony, comes from the Jean Paul novel “Titan – From the Life of a Lonely One” which had a deep influence on Mahler, and which in some ways reflects the inner program of this symphony. However, already in Mahler’s time and even more in our time the word “Titan” is associated with something big and almost monstrous (think “Titanic”), which is really not what Mahler had intended. Therefore, Reinhold decided not to use the title “Titan”, but instead use only the subtitle of this novel “From the Live of a Lonely One”. It is said that this symphony was inspired by two unfulfilled love stories in Mahler’s life: the blonde soprano Johanna Richter (in 1884) and Marion von Weber (in 1888), wife of the grandson of Carl Maria von Weber. These unhappy ending love stories found their reflection in the related song cycle “Songs of a Wayfarer”, which had been composed just before this symphony, and several musical themes and segments from that composition were included in this symphony.

The symphony starts out with a wonderful long sustained quiet beginning, representing an awakening in the morning. Then, the joyous mood sets in, with happiness and exuberant optimism. Following this first movement, the “Flowerine” brings the love theme – “Blumine” is said to be the nickname of Johanna Richter. Mahler has just taken this movement from an earlier, now lost composition “The Trumpeter of Saekkingen”. Some of its elements and motifs are reflected in the other movements of the symphony. The 3rd movement is a happy countryside Laendler, celebrating rural life. After this, the second part of the symphony starts with the fourth movement “Hunter’s Funeral”.

This movement is inspired by a wood carving by Moritz Schwind about a fairy tale, in which the animals of the forest carry the dead hunter to his grave. The music contains a variation of the catholic canon “Frere Jacques” (Brother John), mixed with Jewish Klenzmer-style music from a Bohemian wedding – a parodistic out-of-this-world satire on music. In the middle there is a lyrical interlude from “Songs of a Wayfarer”, again representing love and affection. The final movement “Dall’inferno al Paradiso” does justice to this subtitle, as hell seems to break loose in a furious explosion of emotions. In the end, the “hero” overcomes the trouble and moves on. Here is where the “Titan” attribute may be justified, in victory over bad fate, disappointment, and illusions.

German

Richter, Johanna, Sopran, * 18.8. 1858 Danzig, 1943 Danzig; sie erhielt ihre Gesangsausbildung in ihrer Vaterstadt Danzig und debutierte 1879 dort auch am Stadttheater. 1881 ging sie an das Stadttheater von Mainz, 1882 an das Stadttheater von Bremen und vvurde 1883 an das Hoftheater von Kassel engagiert. Dort verliebte sich der junge Dirigent Gustav Mahler in die schone Sangerin, fand aber keine rechte Gegenliebe. Was sich schliesslich in der (Composition seiner «Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen» niedersehlug.

1886 verliess sie Kassel, ging an das Deutsche Theater in Rotterdam und von dort 1888 an das Opernhaus von Koln. 1890 lebte sie gastierend in Stettin, ging dann aber 1892 wieder ein Engagement am Stadttheatcr von Konigsberg ein, das bis 1895 dauerte. Sie beschloss ihre Buhnentatigkeit mit einer erneuten Bindung an das Stadttheatcr von Danzig in den Jahren 1895-1900.

Sie widmete sich dann noch einer Tatigkeit als Konzertsangerin, zuerst von Berlin, seit 1902 von Danzig aus, wo sie auch im padagogischen Bereich wirkte. Zu ihren Buhnenrollen gehorten die Leonore in «Alessandro Stradella» von Flotow, die Titelfigur in «Martha» vom gleichen Komponisten, die Marie in Donizettis «Regimentstochter», der Page Oscar in Verdis «Maskenball», die Philine in «Mignon» von A. Thomas, die Isabella in «Robert le Diable» von Meyerbeer und die Frau Fluth in den «Lustigen Weibern von Windsor» von Nicolai.

And

Johanna Emma Richter never had a career of more than mediocre success. She was offered a contract with the Kassel opera after appearing as a guest artist there in spring 1883. She left after four years and, throughout her singing career, rarely stayed longer than that in any one place. She finally retired from the stage about 1906, and earned her living thereafter giving singing lessons and recitals. She lived at least until 1943 (when she was in Danzig, or, as it is called today, Gdansk), but there is no indication that she ever married, nor do we have any way of knowing whether she herself was aware of her role in inspiring Mahler’s earliest masterpiece.